21 Infographic Panels PDFs for Shroud of Turin Expositions. Download link:

https://mega.nz/folder/xi4g1LLA#qXtqMYIWw7WoqeRWPpE_Qw

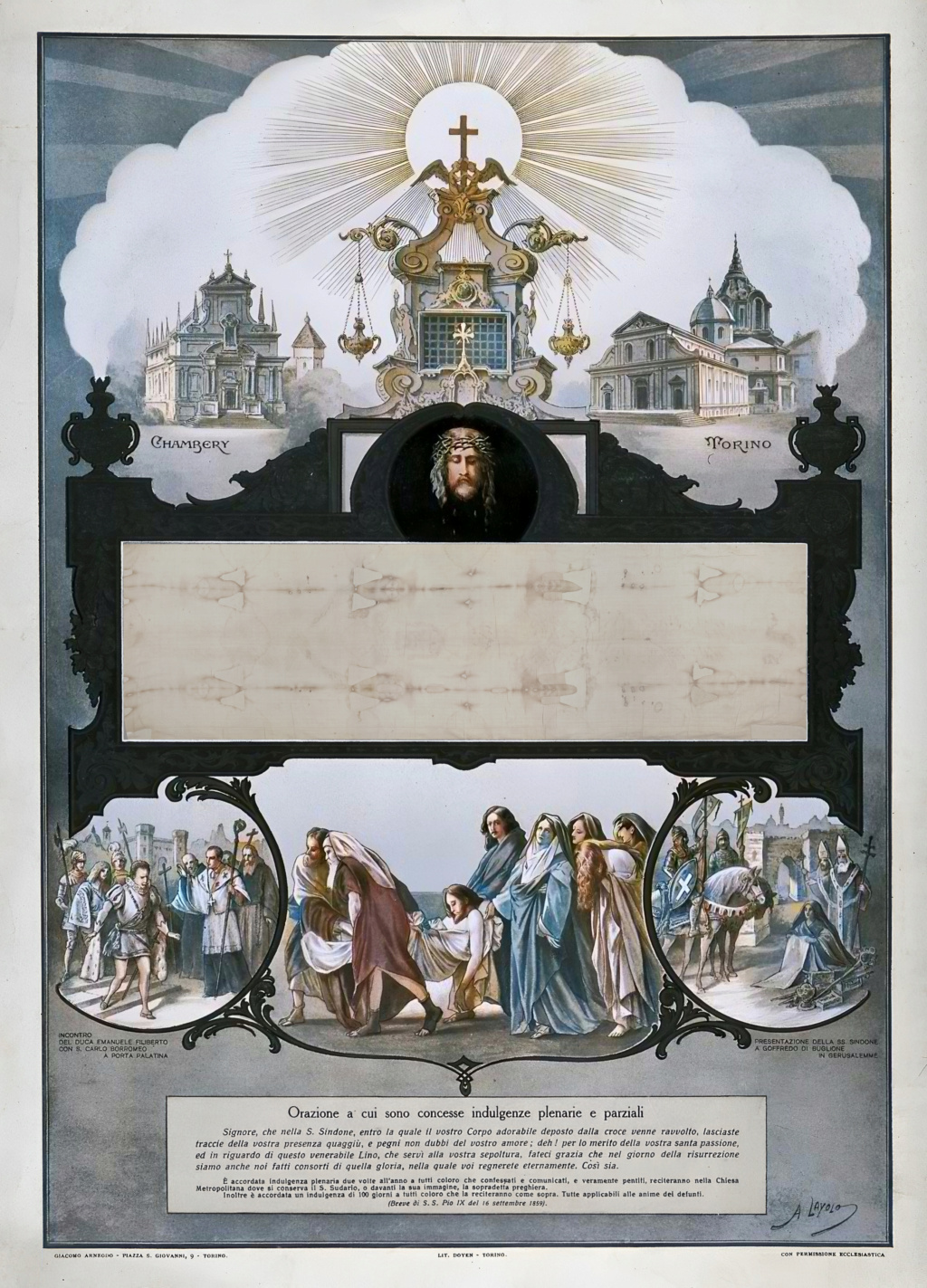

Panel 1 Intro and history

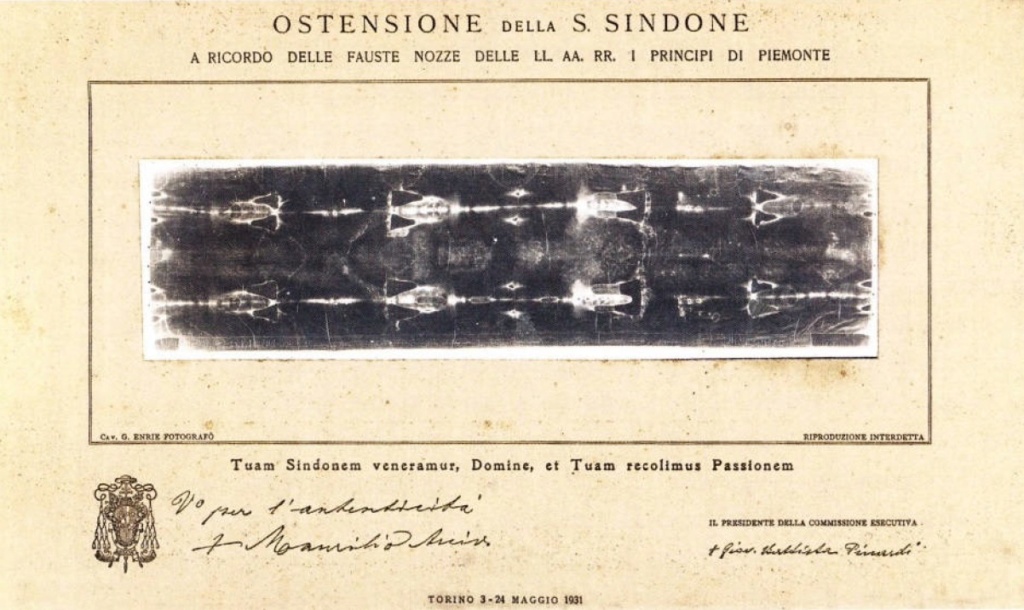

Panel 2 History of the Shroud

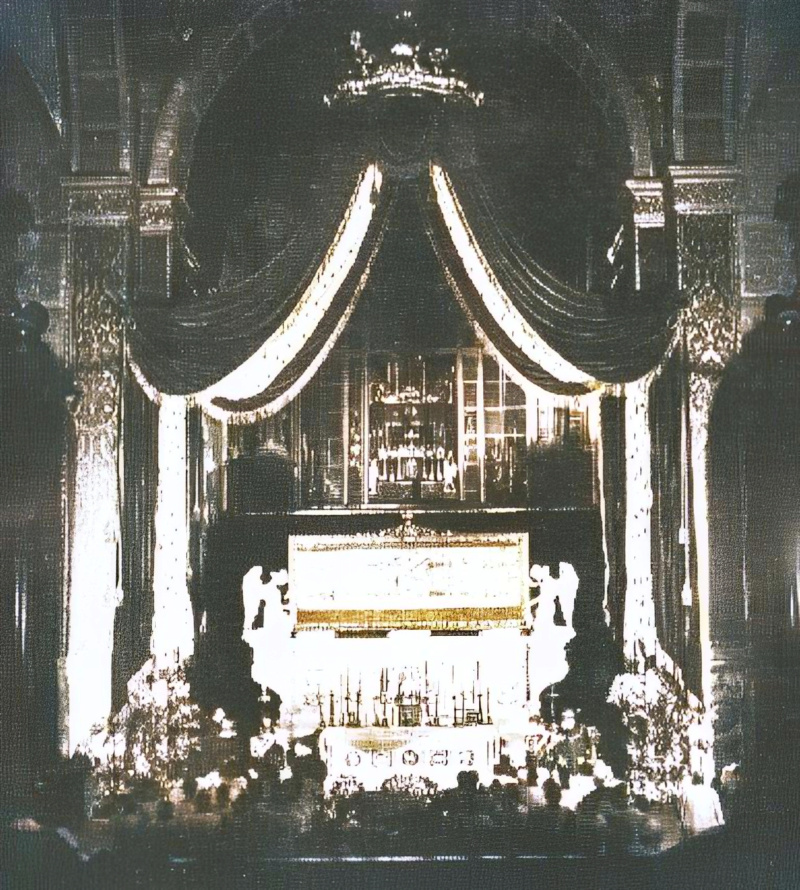

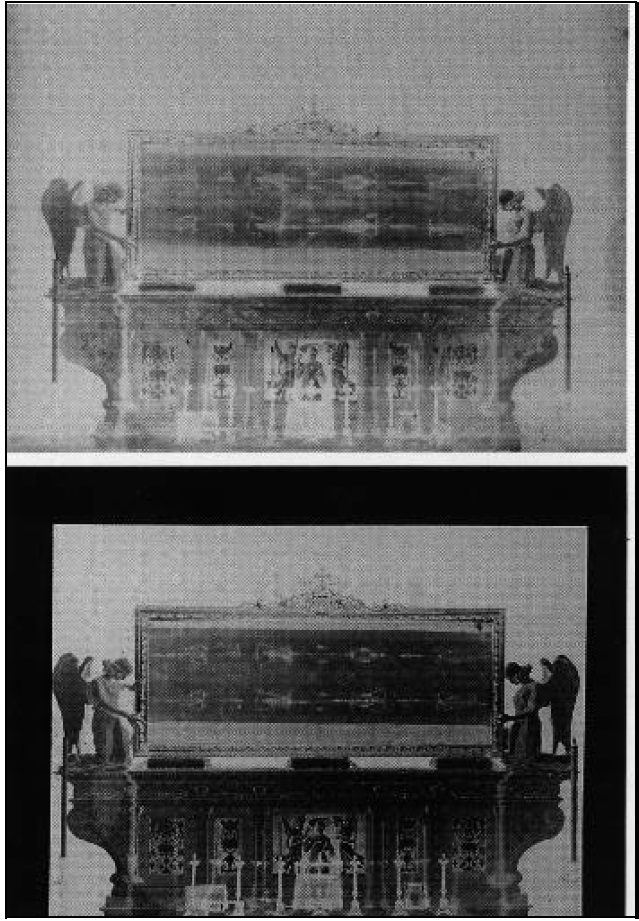

Panel 3 6th. to 14th. century of the Shroud

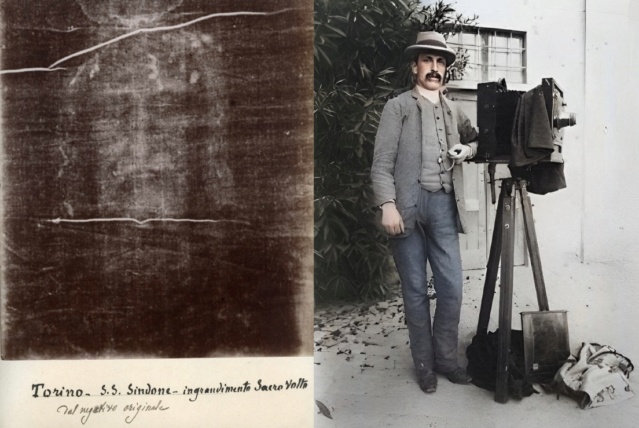

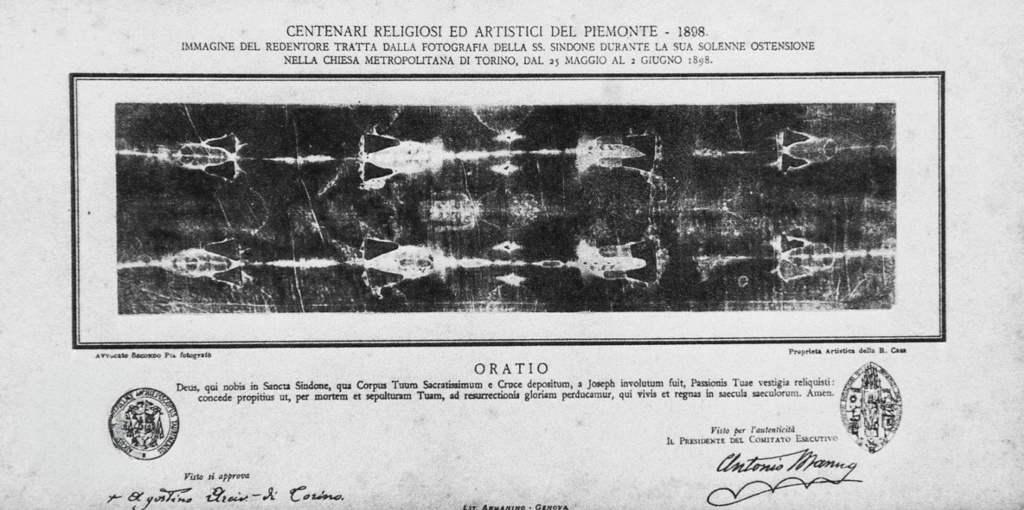

Panel 4 Secondo Pia's 1898 discovery

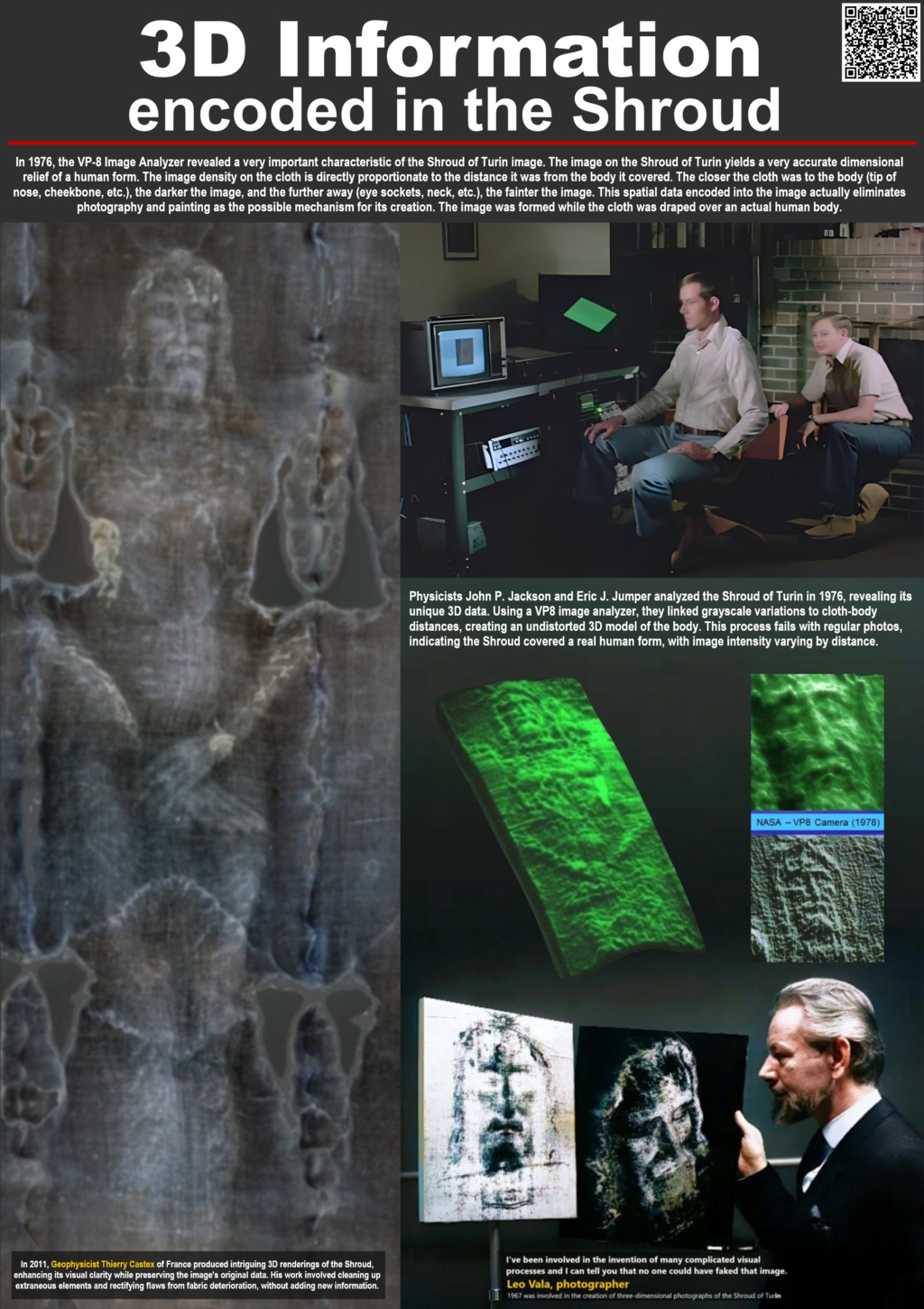

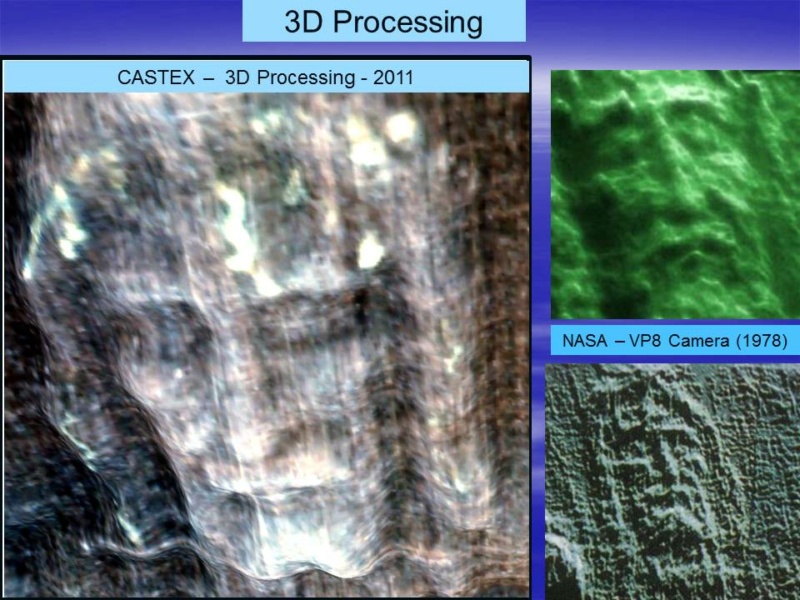

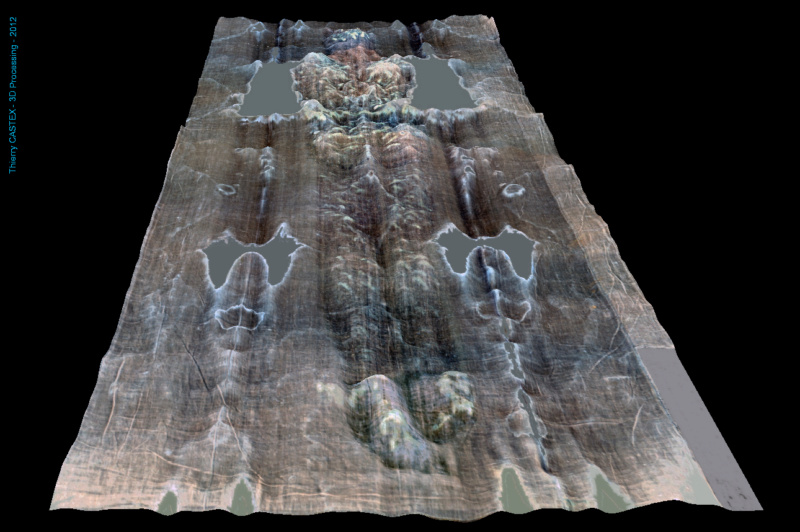

Panel 5 3d information on the Shroud

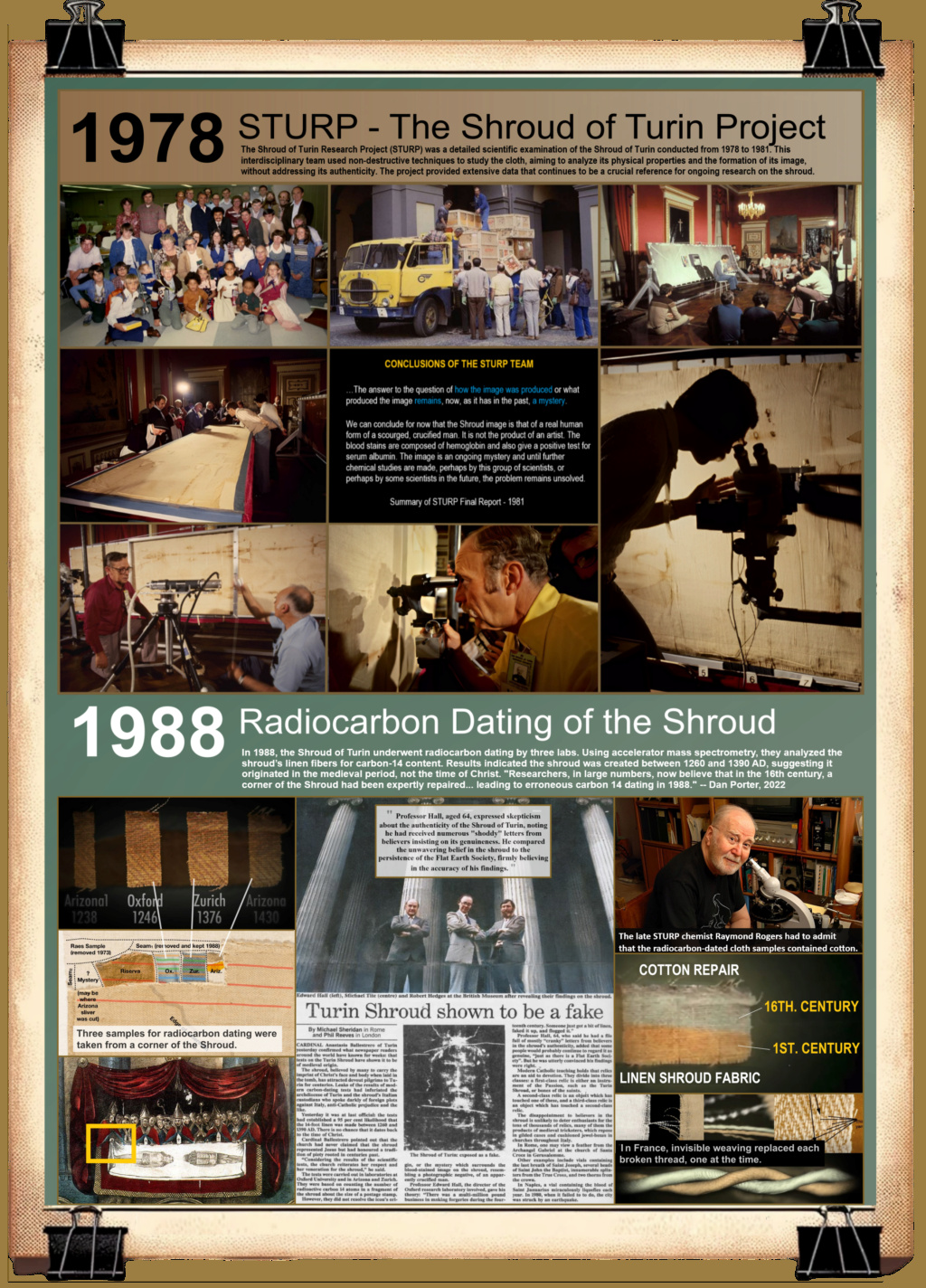

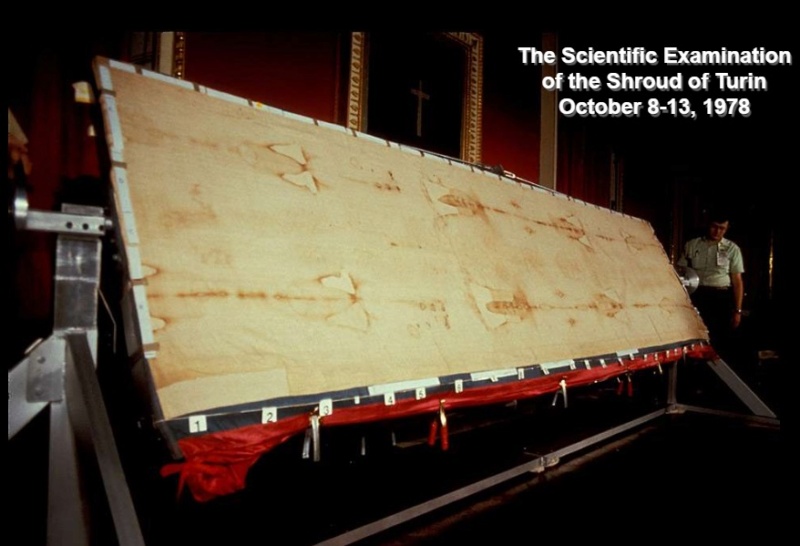

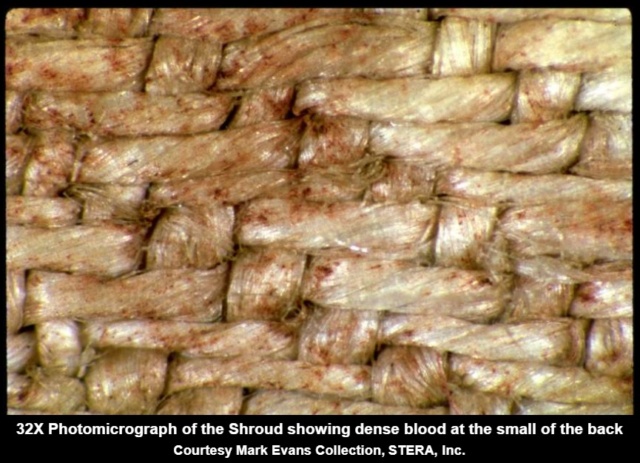

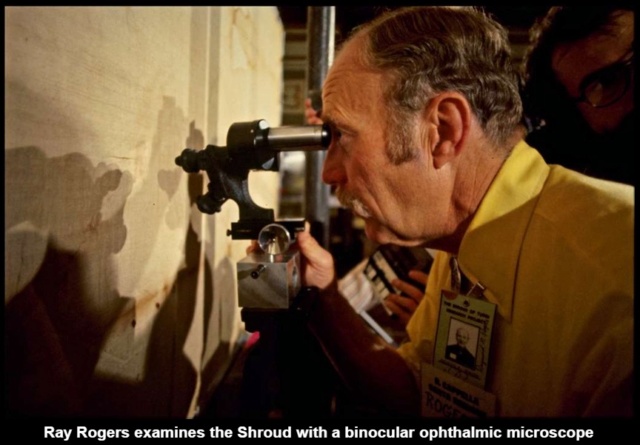

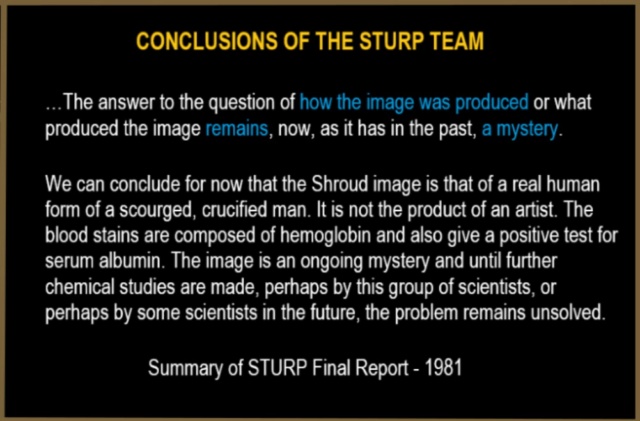

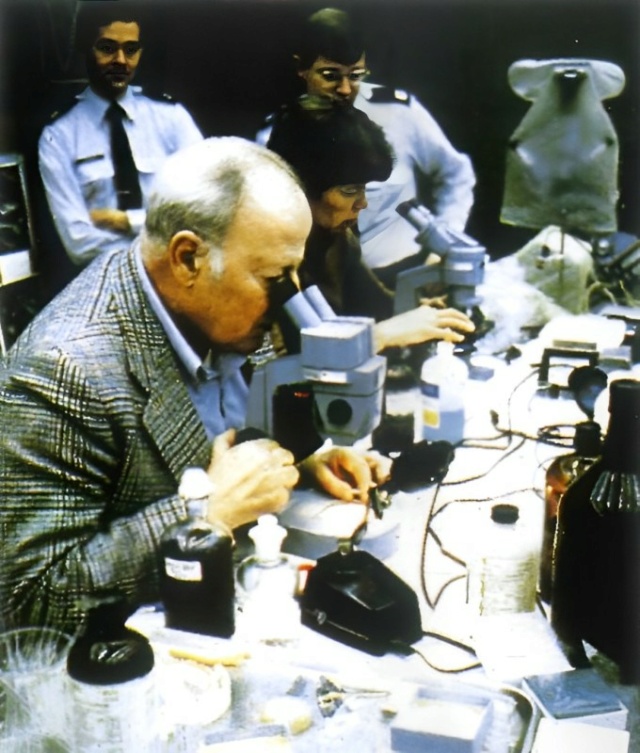

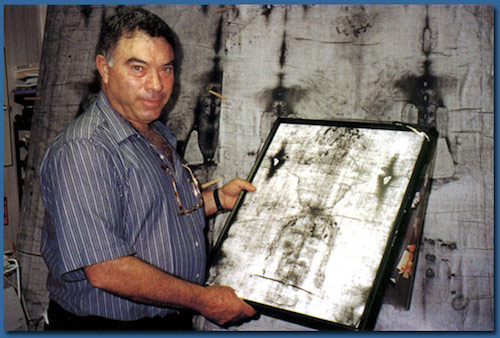

Panel 6 STURP and Radiocarbon dating

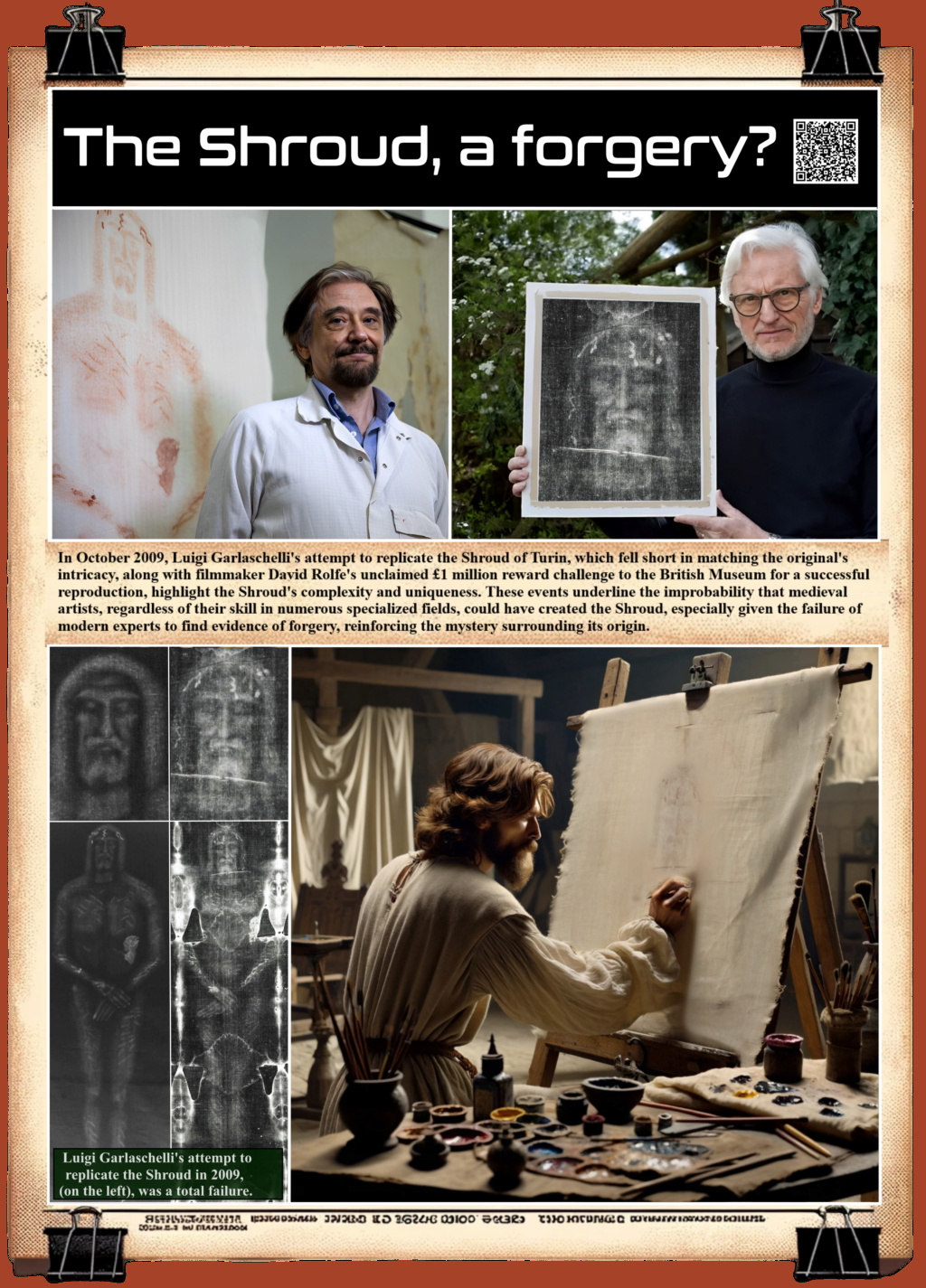

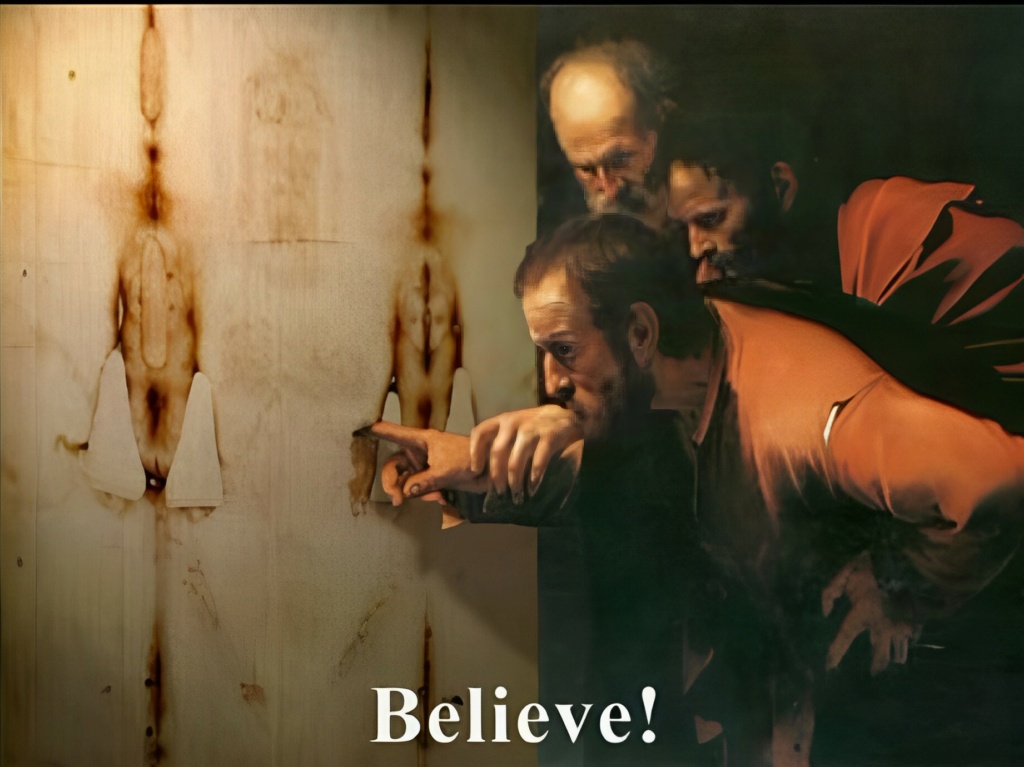

Panel 7 The Shroud, a forgery?

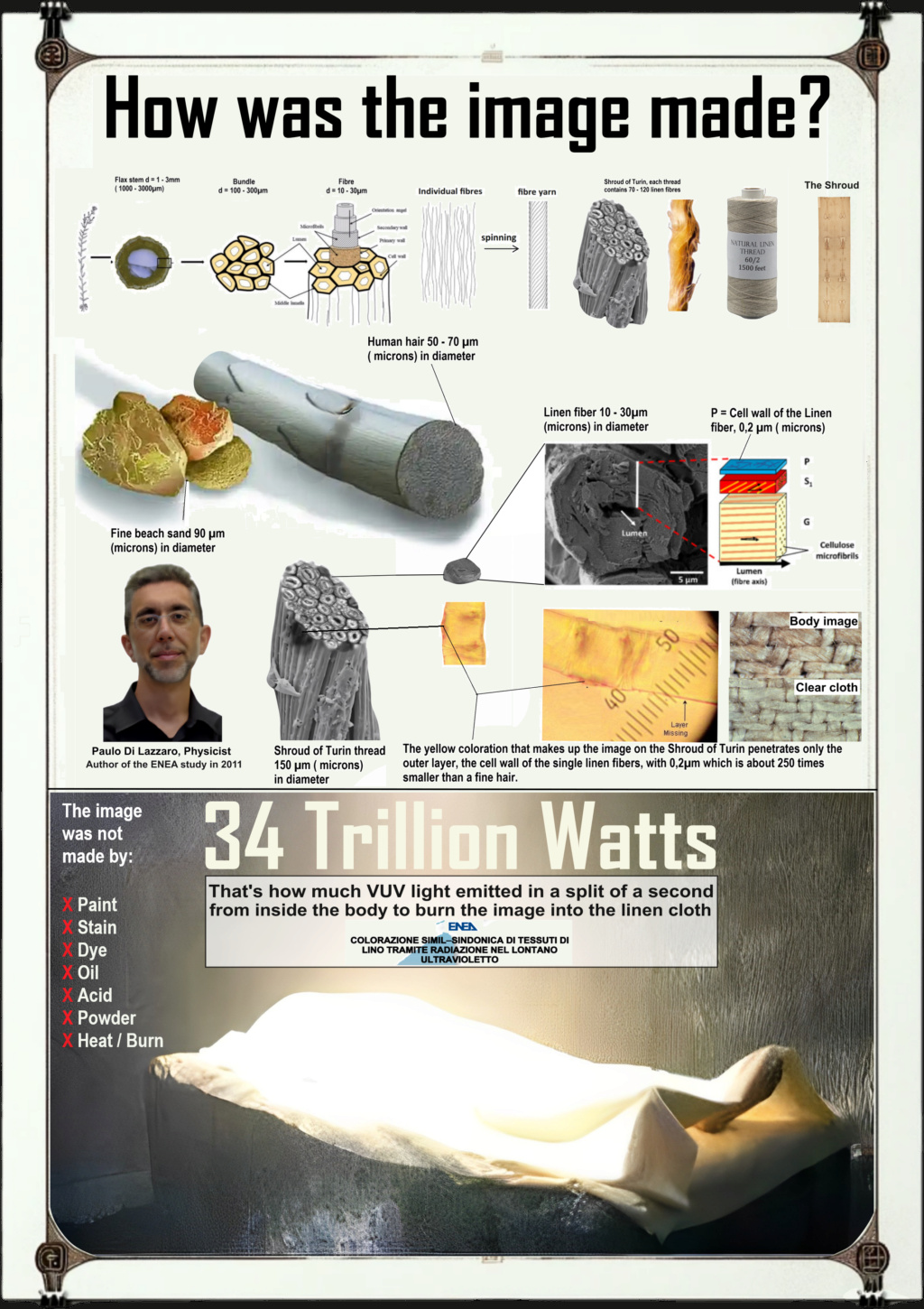

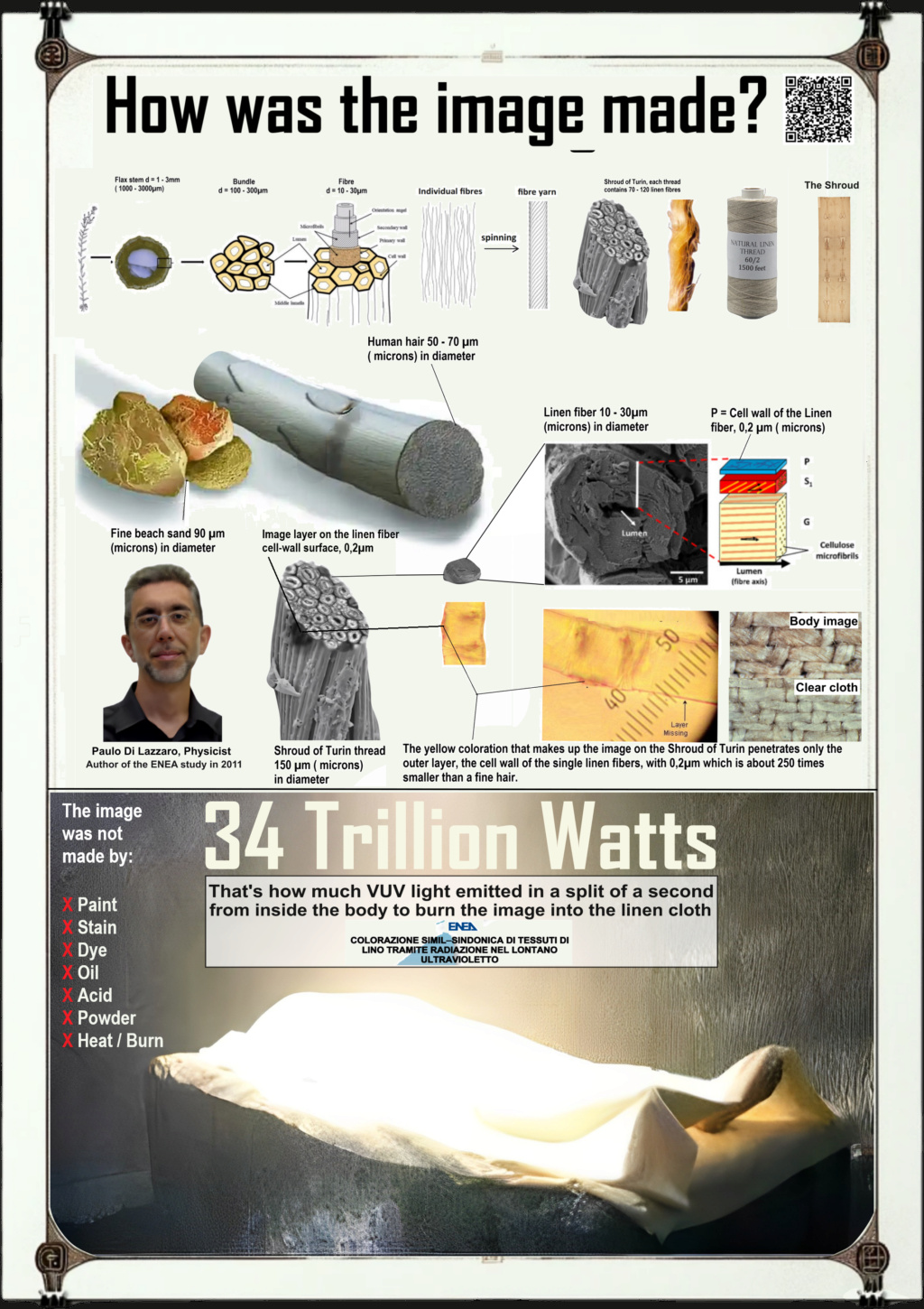

Panel 8 How was the image made?

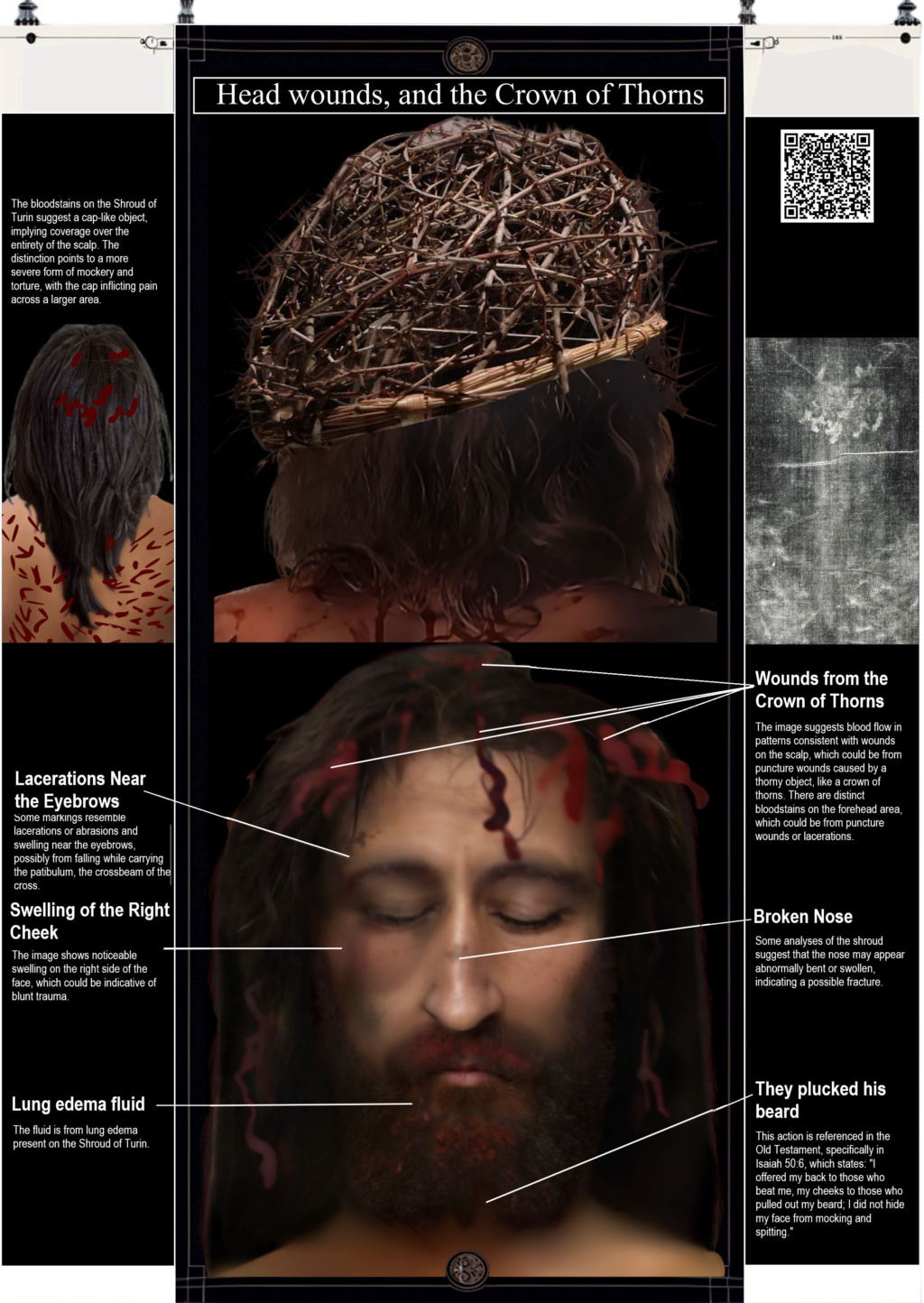

Panel 9 THE FLAGELLATION

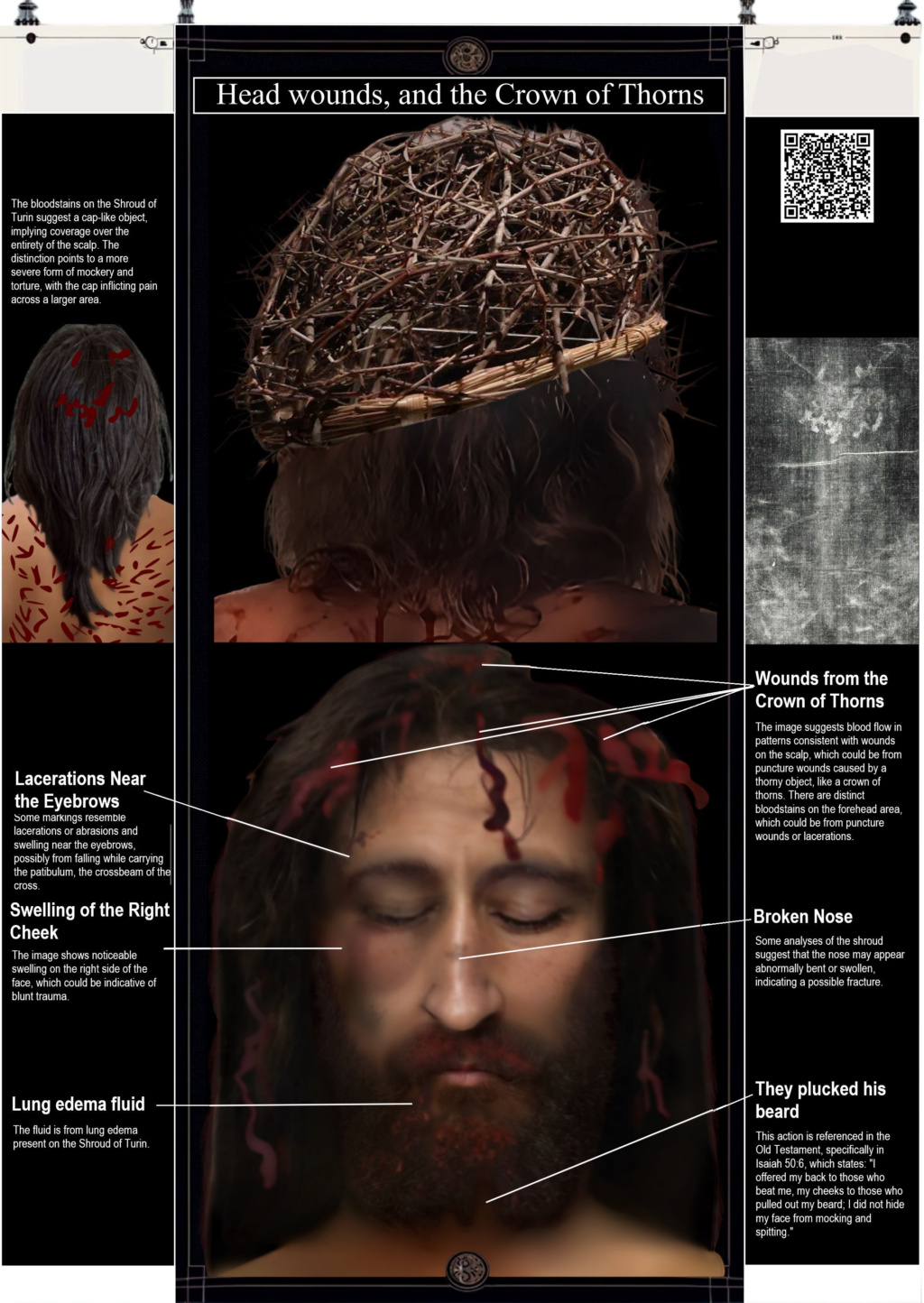

Panel 10 HEAD WOUNDS, AND THE CROWN OF THORNS

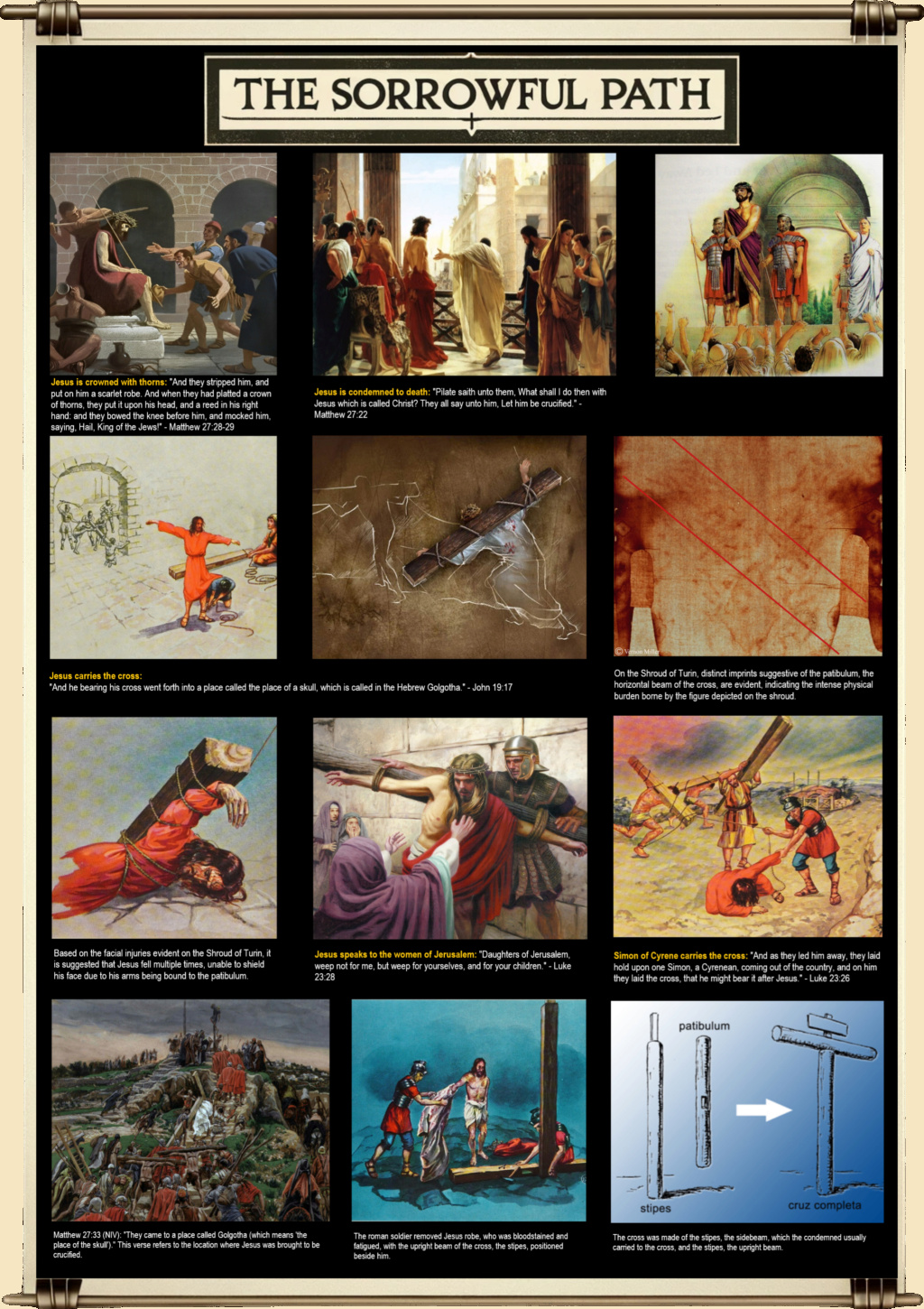

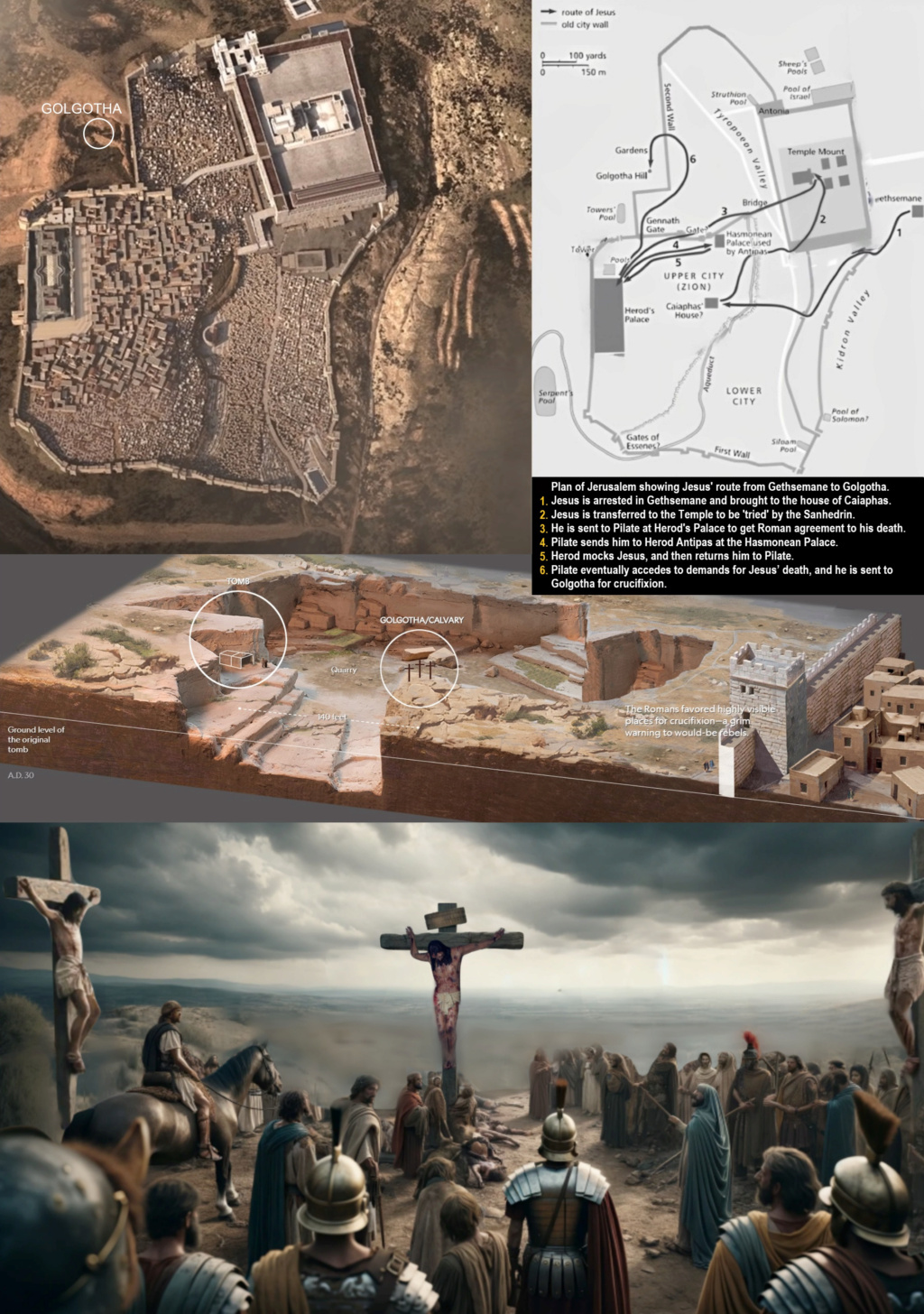

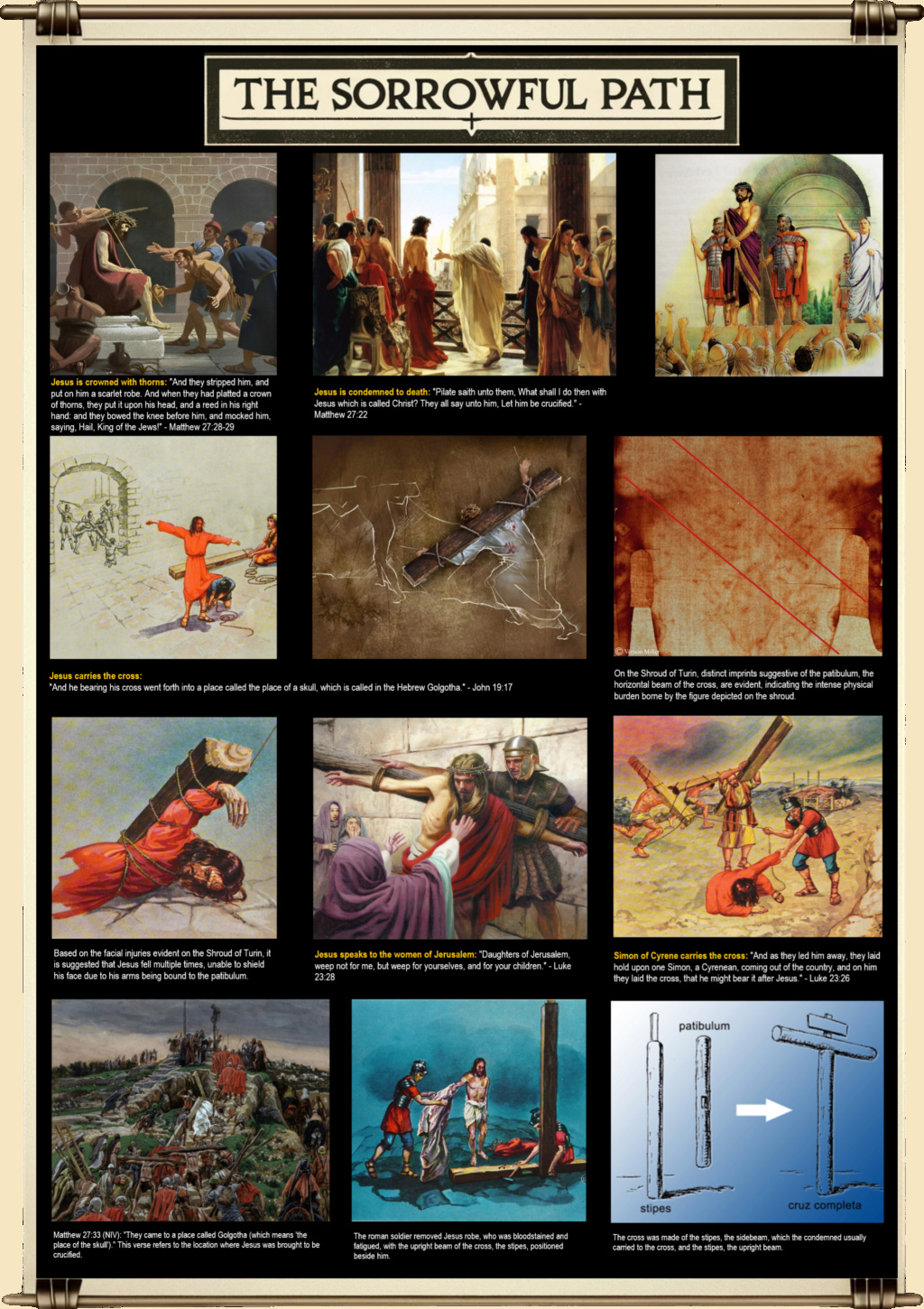

Panel 11 TOWARDS CALVARY

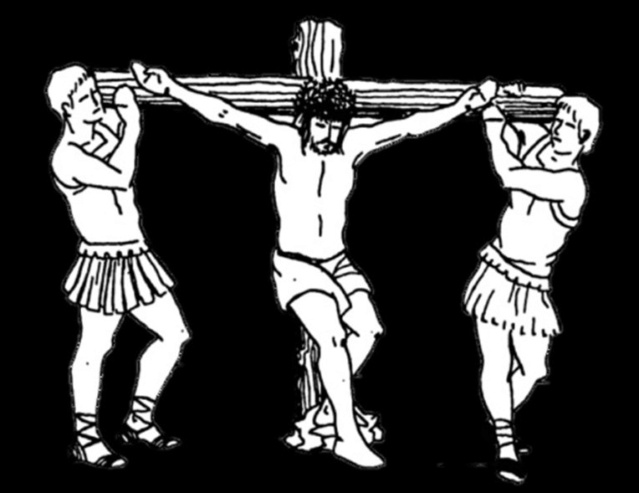

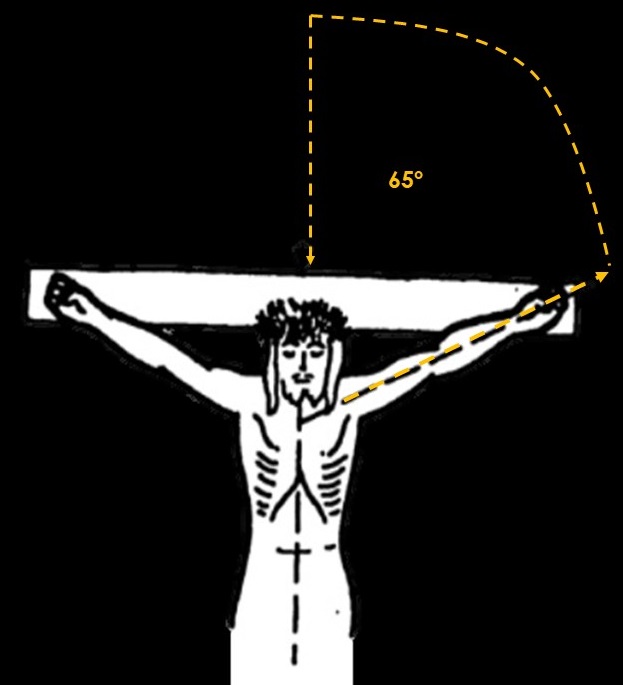

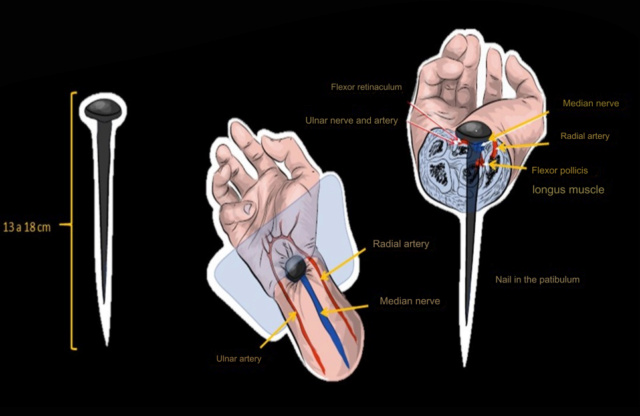

Panel 12 GOLGOTHA/CALVARY

Panel 13 THE CRUCIFIXION

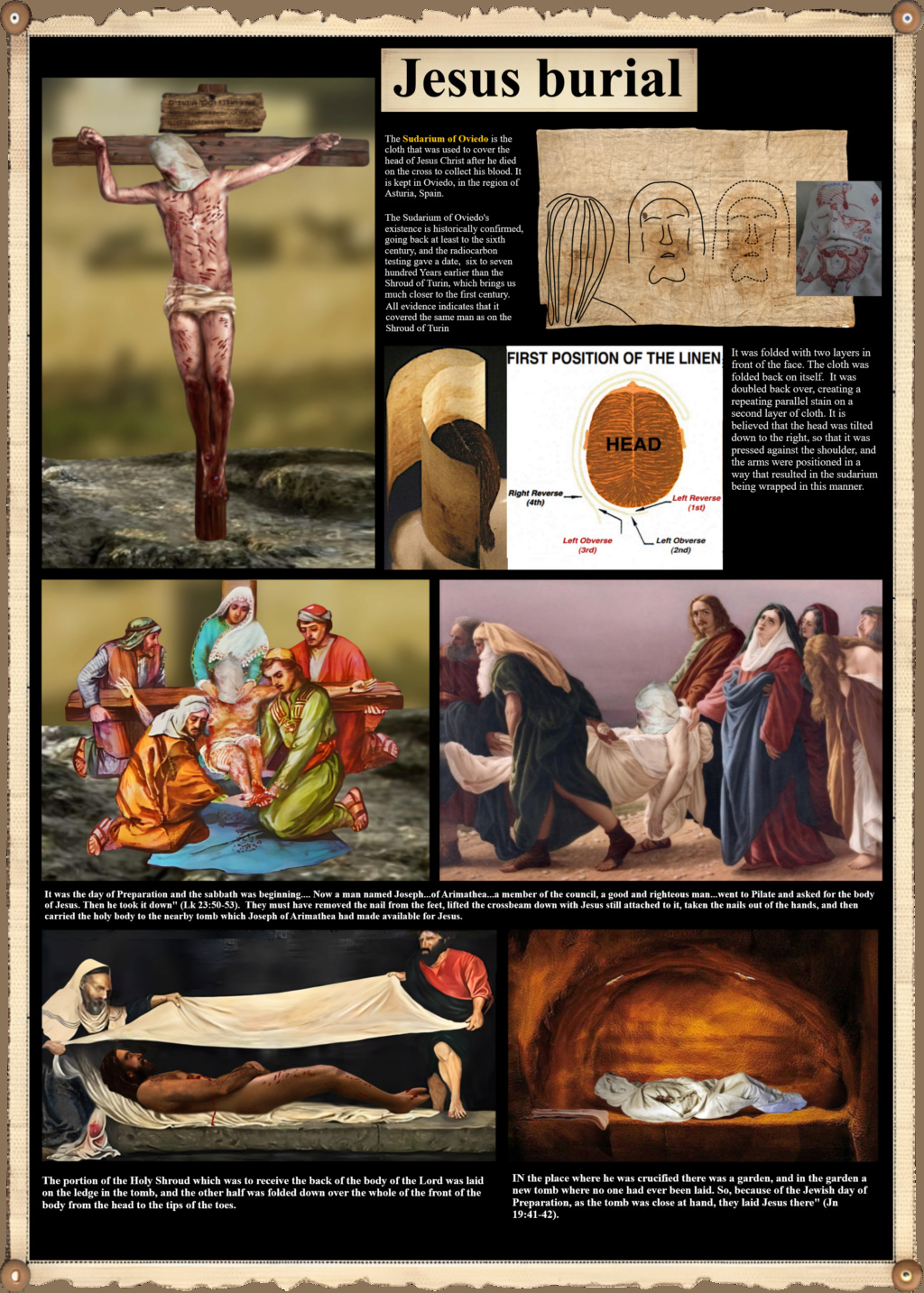

Panel 14 THE DEATH

Panel 15 THE BURIAL

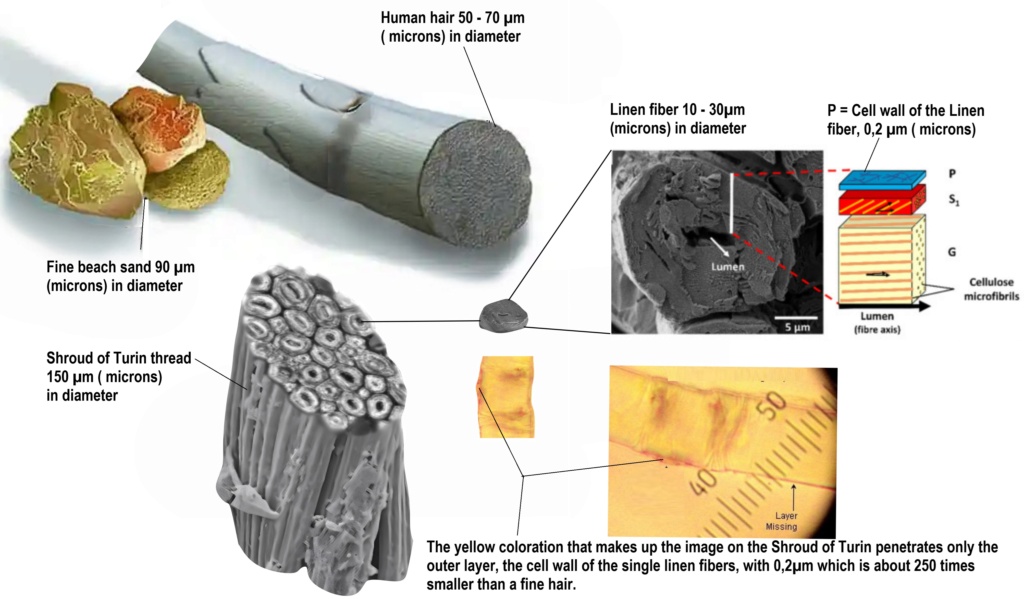

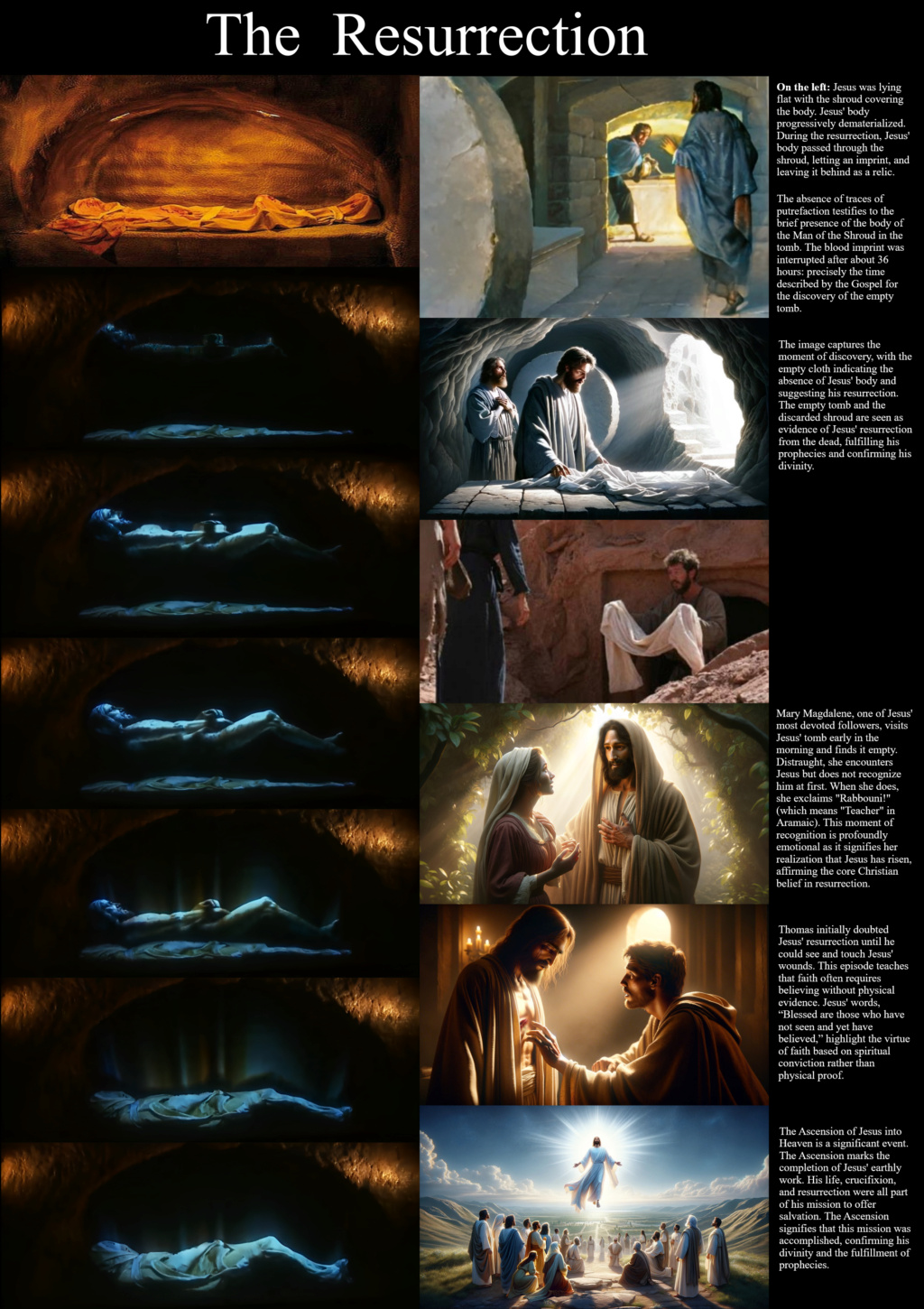

Panel 16 THE RESURRECTION

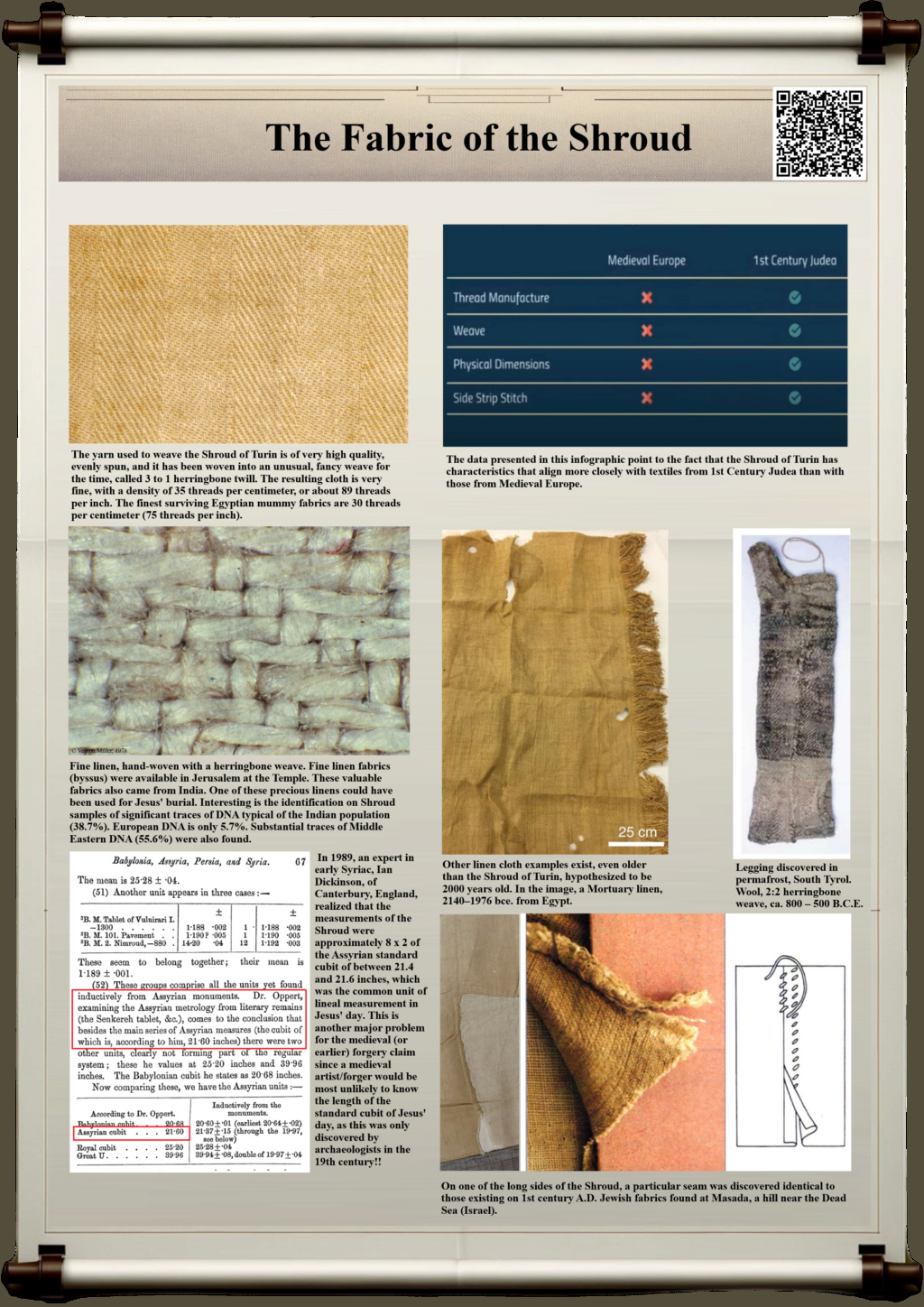

Panel 17 The Linen

Panel 18 The Blood

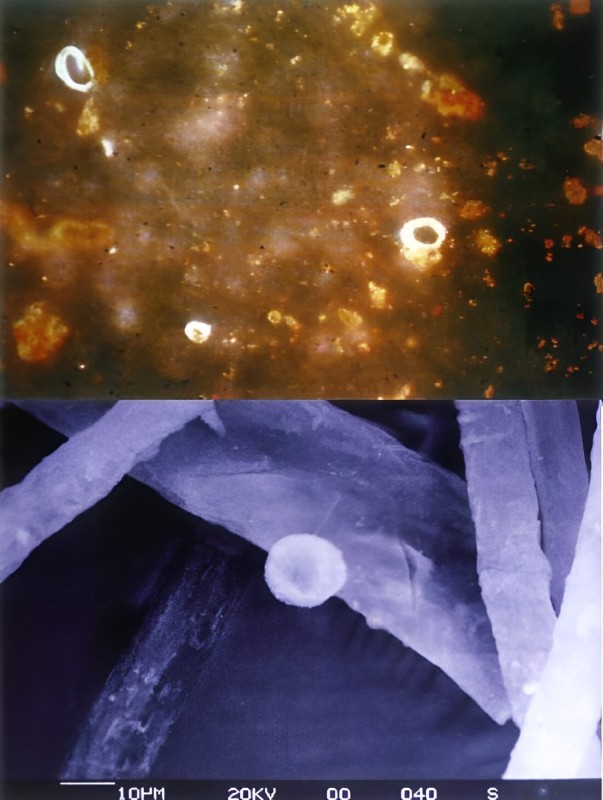

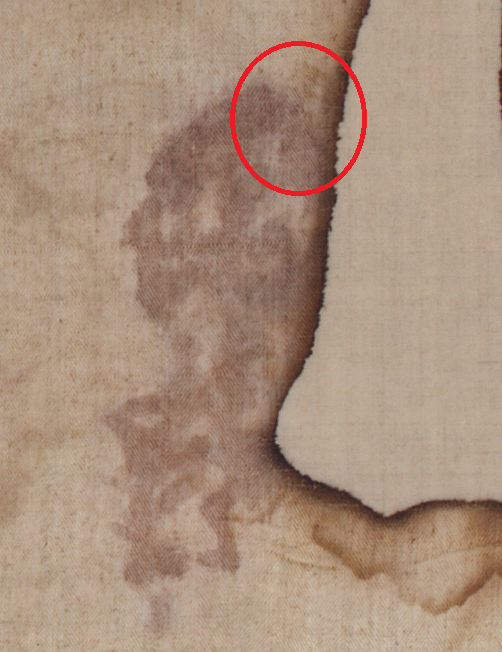

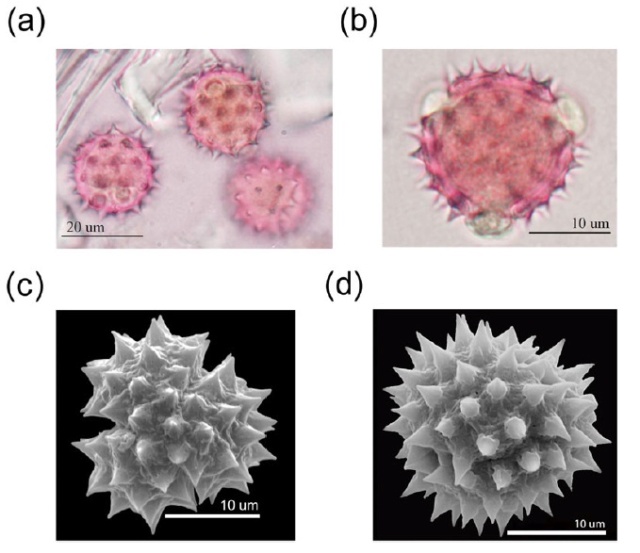

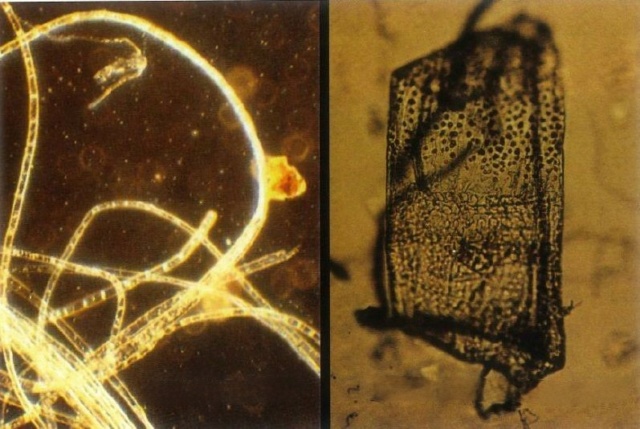

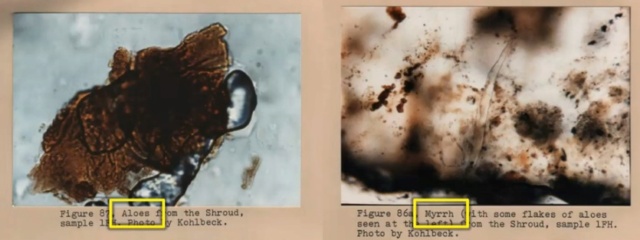

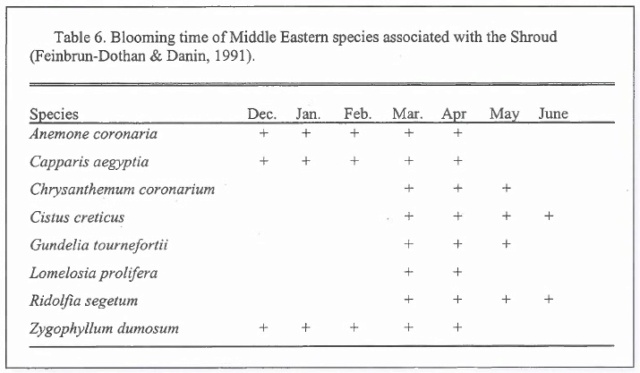

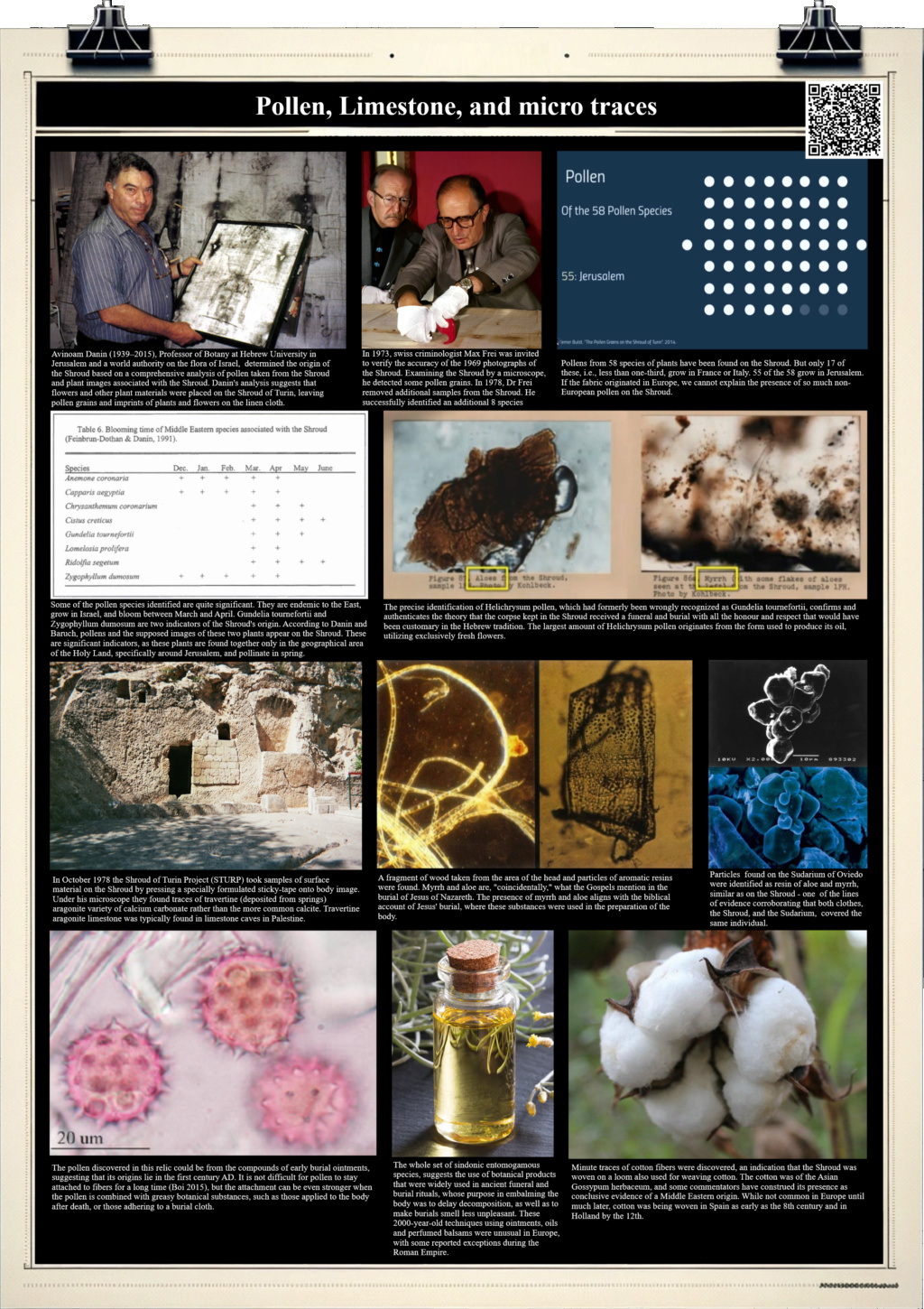

Panel 19: Pollen, Limestone, and micro traces

Panel 20 BOUGHT, PURCHASED, RANSOMED & REDEEMED

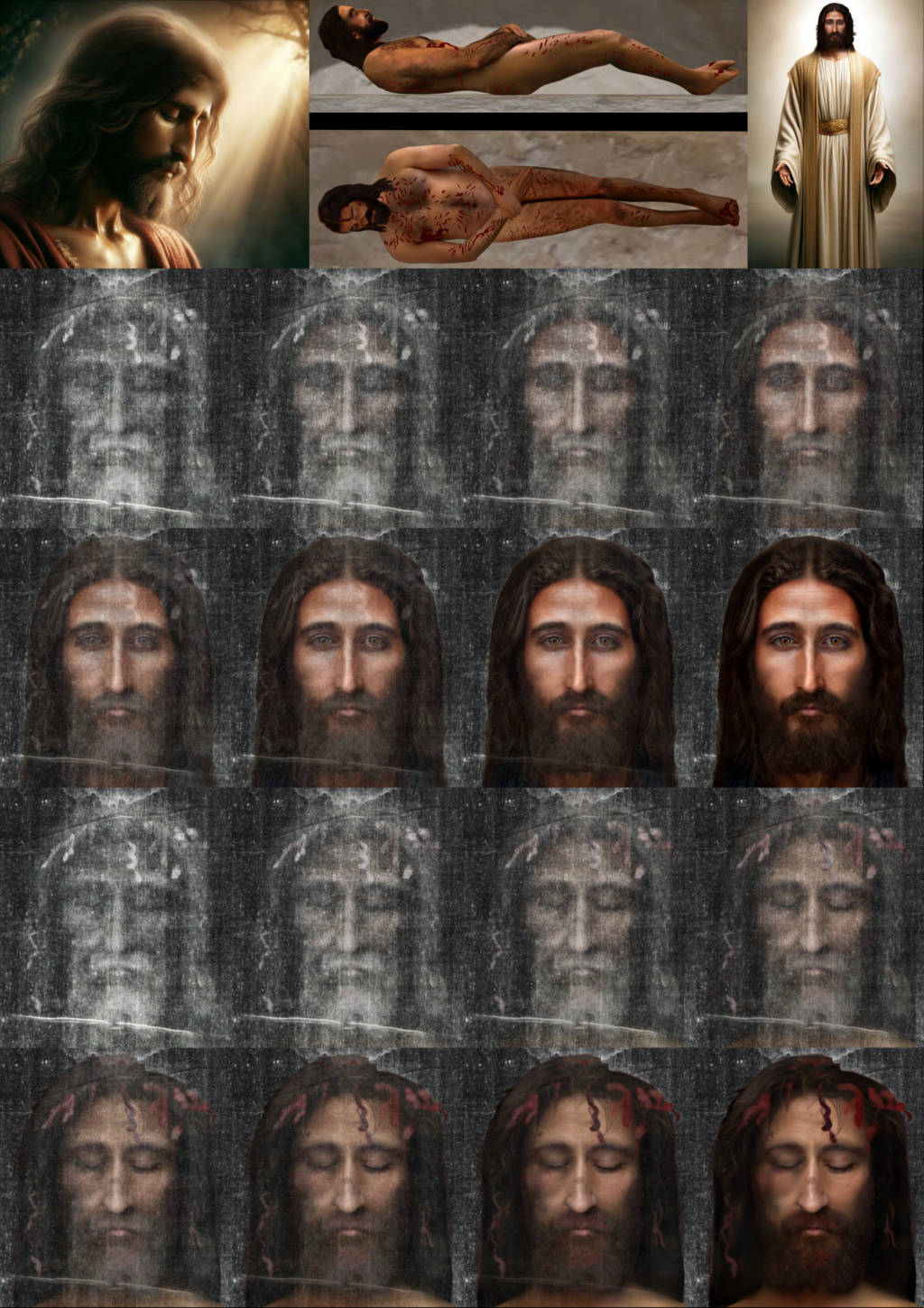

Panel 21 SOME RENDERINGS

Panel 1

Panel 2

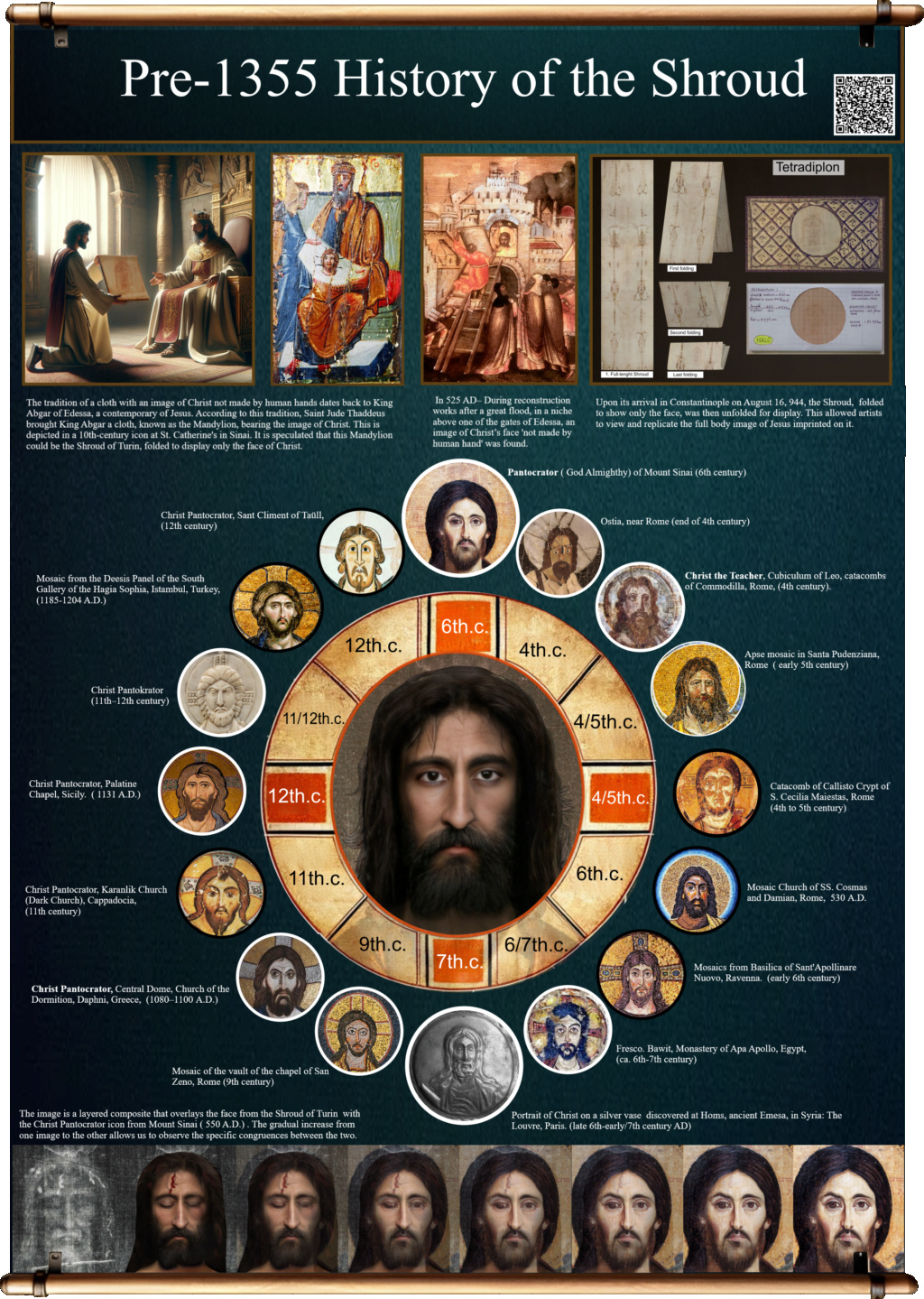

Pre-1355 history of the Shroud: Evolution of Christ Iconography

The Bible offers no detailed description of Christ's physical features; instead, tradition credits Saint Luke or Nicodemus with crafting the first depictions of Jesus.

In early Christian art, symbolism was predominantly employed, utilizing motifs like the lamb, the loaf, and particularly the fish. The Greek acronym for 'Jesus Christ, Son of God, Savior' spelled out 'fish,' and depictions of the 'eucharistic fish' are notable in the San Callisto catacombs in Rome, dating back to the late 2nd century.

The initial visual portrayals of Christ in ancient mosaics and sculptures were influenced by deities from various non-Christian beliefs, a reflection of the era's gradual shift from paganism to Christianity. One of the earliest known images, Christ Helios, located in the Vatican's Tomb of the Julii from the early 3rd century, depicts Jesus as the unconquered sun, sol invictus, ascending to the heavens in a chariot pulled by two horses.

With time, the depiction evolved to include the human form of Christ as the 'good shepherd,' 'healer,' and 'teacher and guide,' reminiscent of the classical archetype akin to Apollo. Such an image is exemplified by the portrayal of Christ healing the bleeding woman, found in the catacombs of Saints Peter and Marcellinus in Rome from the late 3rd century. The portrayal of a beardless Christ was likely a deliberate choice to emphasize his divine essence, aligning with the proclamations of the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD about the divine nature of Jesus, the Son of the eternal God.

Image 2b:

The Image of Edessa, also known as the Mandylion, is intertwined with the tale of how Christianity came to Edessa. The legend of the Mandylion claims that Taddai brought the Shroud soon after 33AD to Edessa. This story is told in the document known as "The Teaching of Addai," a text that dates back to the late 4th or early 5th century. According to tradition, King Abgar V of Edessa, suffering from an illness, heard of Jesus Christ's miraculous healings and sent a correspondence to him, requesting both healing and that Jesus seek refuge in his city. In the account recorded in "The Teaching of Addai," rather than Jesus Himself visiting Edessa, He sends one of His disciples, Thaddeus (also referred to as Addai), in His stead after the Ascension. Thaddeus arrives in Edessa, heals King Abgar, and facilitates the conversion of the king and his subjects to Christianity.

The Image of Edessa

For more on the image of Edessa, see here

The Image of Edessa, also known as the Mandylion, is an integral part of Christian history and iconography, with its roots deeply embedded in the legend of how Christianity came to the ancient city of Edessa. This tale is chronicled in the document "The Teaching of Addai," dating back to the late 4th or early 5th century. The story begins with King Abgar V of Edessa, who suffered from a severe illness. Upon hearing of Jesus Christ's miraculous healings, Abgar sent a correspondence to Jesus, inviting Him to Edessa for healing and refuge. According to "The Teaching of Addai," Jesus, unable to visit Edessa himself, sent his disciple Thaddeus (also known as Addai) after His Ascension. Thaddeus arrived in Edessa, healed King Abgar, and led the conversion of the king and his subjects to Christianity.

The Mandylion, meaning "towel" or "handkerchief" in Greek, is central to this narrative. It is believed to bear a miraculous image of Jesus' face. There are different accounts of its origin; some suggest Jesus intentionally imprinted His face on the cloth, while others claim the image appeared when He wiped His face with it. This revered cloth, sent to King Abgar, validated his faith and veneration. An interesting twist in the story involves Hanan, the king's messenger, who in some accounts is tasked with painting Jesus' likeness. However, he returns with the Mandylion, bearing the divine imprint of Christ's visage, instead of a crafted image. This event marks the beginning of the veneration of the Image of Edessa, considered one of the earliest icons in Christian history.

The Image of Edessa also played a significant role during the Iconoclastic Controversy in the Byzantine Empire. It served as an exemplar for the defense of icon veneration, notably by figures such as St. John Damascene. The argument was that if the Mandylion, an image "not made by human hands," was worthy of honor, then so were other icons. The legend further unfolds during the siege of Edessa by Persian forces in 544. The city's bishop, following a prophetic dream, unearthed the Image, which was hidden in a wall niche. When brought to the siege lines, the Image caused a miraculous event: the flames lit by the besiegers were repelled, leading to their defeat.

Despite Edessa's eventual fall to the Byzantine Empire, the Image remained revered and was transported with great ceremony to Constantinople in the 10th century. Housed in the Boucoleon Palace, it made occasional appearances in pilgrims' accounts but ultimately vanished following the sacking of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade in 1204. The Image of Edessa, beyond its physical existence, left a profound textual and symbolic legacy. It played a crucial role in the early establishment of Christianity in the region, evidenced by Edessa becoming the first kingdom to embrace Christianity as a state religion around 200 AD. During the Iconoclast Controversy, the Image became a central piece of evidence in the debate over the veneration of sacred images, embodying the concept of circumscription. This concept, highlighting Christ's ability to be depicted, was pivotal in justifying the use of religious imagery. The Image's symbolic and protective roles continue to resonate within the Orthodox Church, influencing Christian iconography. Its placement over gateways in Edessa reflects the Church's appropriation and Christianization of earlier pagan traditions, such as the ancient Greek practice of positioning statues of deities at city gates for protection. This adaptation showcases the seamless weaving of old and new traditions in the continuous tapestry of faith and tradition, with the Christian Image of Edessa supplanting and transforming earlier practices.

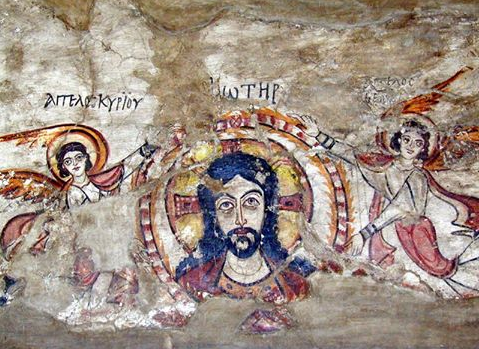

Image 2c:

There are several reasonable clues suggesting that the events narrated in the Doctrine of Addai have a historical basis and refer to Abgar V, who reigned during the time of Jesus. When he died in 50 A.D., his son Ma'nu V succeeded him. Upon the latter's death in 57 A.D., the kingdom was passed into the hands of Abgar V's other son, Ma'nu VI, who reverted to pagan worship and persecuted Christians. It is, therefore, reasonable to assume that the image had to be hidden, and its precise memory faded until its rediscovery in the 6th century. By the times of Eusebius and Egeria, it was no longer possible to display the image; this could explain their silence on the matter.

In 57 A.D., Ma'nu, the successor of Abgar, rejects Christianity and begins to persecute Christians. The cloth is hidden and disappears. In 525 AD– During reconstruction works after a great flood, in a niche above one of the gates of Edessa, an image of Christ’s face 'not made by human hand' was found. It is the Mandylion (Shroud), whose imprinted face was similar to what we have on the Shroud of Turin.

In the account given by the compiler of the Narratio, the acheiropoieton image had been displayed openly but was later concealed within a wall, or possibly within a column or a small shrine at the city's gate, as often depicted. This image, by some accounts, was miraculously preserved through numerous calamities, including several devastating floods that battered the city in the years 201, 203, 413, and 525, and its existence had slipped from the collective memory of the people.

The tale then reconnects with a tradition begun by Evagrius Scholasticus, who recorded that in 544, during the Persian siege of Edessa, the city was spared due to the presence of this relic. However, by that time, the inhabitants had forgotten about this potent talisman. The narrative introduces a dramatic turn where the bishop of Edessa is guided by a dream vision to rediscover the hidden object. Upon following the revelation, the bishop finds the divine image intact, along with a wick that had remained lit over the centuries, and a secondary image on a tile that was placed before the lamp to shield it. Armed with the venerable depiction of Christ, the bishop then approaches the area where the Persian forces were heard, reinforcing the city’s hope.

The image, having been found unscathed after such a long concealment, was credited with the miraculous repulsion of Chosroes and his forces. The account of the Narratio thus explains the existence of more than one terracotta tile bearing the miraculous image of Christ.

The story provides an intricate account of how an image, preserved through time, was later found and became a symbol of protection and victory for the city of Edessa. The tale also touches upon the tradition of placing anthropomorphic symbols on buildings, a practice common in the region, which could relate to the placement of the image on the city gates. Further, it recounts the finding of a lamp that had seemingly burned perpetually, and a ceramic representation of the image that was potentially used to safeguard the actual relic when placed within its niche.

The earliest known historical mention dates to 544 AD, when the Persian King Khosroes besieged Edessa. The city reportedly repelled the siege with the aid of the image, described by historian Evagrius Scholasticus as miraculously made "not by the hands of man"—a phrase commonly associated with the Mandylion.

The Image of Edessa, also referred to as the Mandylion, holds a significant place in the lore of Christian relics, embodying a profound intersection of faith, art, and history. The phrase "not made by hands" (acheiropoietos in Greek) that Evagrius Scholasticus and other sources use to describe the image conveys the belief that the image was of divine, rather than human, origin—miraculously created.

The account of the siege of Edessa and the image's role in it appears to be the first historically recorded instance of the Mandylion. When the Persian forces of King Khosroes I laid siege to the city, the Edessans processed the holy image along the city walls, which resulted in the miraculous saving of the city. This event elevated the Mandylion to the status of a palladium, a protective icon for the city.

The historical account given by Evagrius does not mention the legend of King Abgar and the image’s origins, which suggests that the association with the earlier legend developed after this time. It is also notable that the earlier story about the image's origins in the time of Jesus does not specify the image's nature as acheiropoietos, a detail that appears to emerge later and may reflect a growing theological emphasis on the divine nature of Jesus and the desire for a tangible connection to Him. By the 6th century, the cult of icons was becoming increasingly popular, and the story of the Image of Edessa played a pivotal role in this development. Icons were not merely artistic representations but were believed to participate in the holiness of the figures they depicted, serving as conduits for devotion and intercession.

The Mandylion remained in Edessa until the 10th century, after which it was brought to Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire. Its arrival is historically documented in 944 AD, when it was transferred with great ceremony. The Byzantines also regarded the image with profound reverence, and it was believed to have the power to protect the city. The fate of the Mandylion following the Fourth Crusade in 1204, when Constantinople was sacked by Latin Crusaders, is uncertain. Some scholars believe that the Mandylion was taken to the West and eventually became what is known today as the Shroud of Turin, although this theory is subject to much debate and is not universally accepted. Throughout its history, the Mandylion has been enveloped in legend and mystery. While its existence as a physical artifact from the time of Jesus is debated, its impact on Christian tradition, iconography, and the veneration of relics is clear. It served as a symbol of Christ's presence and a tangible embodiment of divine intervention in human affairs. Its story is a testament to the enduring human desire for a direct, physical connection to the divine and the powerful role that religious artifacts play in faith and community identity.

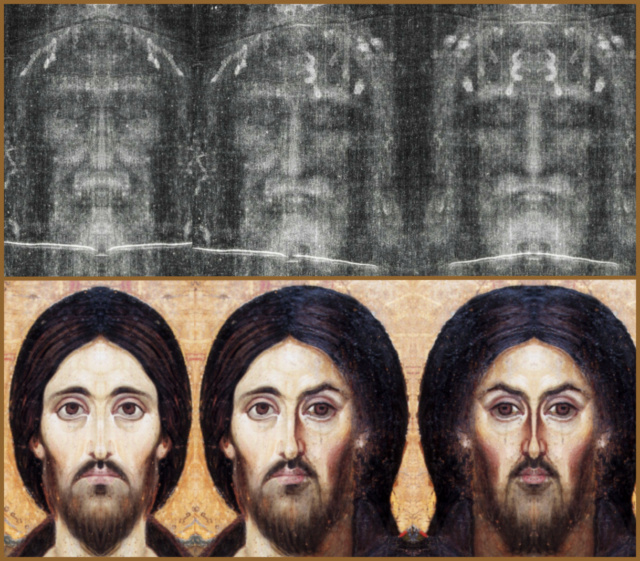

The legend of the Mandylion states that the image, which had been hidden due to the city's conversion back to paganism, was rediscovered after a vision on the night of a Persian invasion. The story evolved to include the idea that the image was not made by human hands (Acheiropoietos), and later accounts suggest it played a role in the defense of the city during the siege by Persian King Khosrow I in 544 AD. However, there is strong evidence against this narrative, as the Syriac "Edessan Chronicle," written between 540 and 550 AD, does not mention the rediscovery of any image following the 525 flood, which challenges the theory that the Mandylion/Shroud was found at that time. The earliest mention of an image in this context appears in the Doctrine of Addai from around 400 AD, which describes a portrait of Jesus painted by a court painter. Over time, the story developed to include supernatural elements, such as the image miraculously reproducing itself on a tile and remaining lit by a lamp over centuries. The Christ Pantocrator at St. Catherine's Monastery in Sinai is considered one of the earliest icons to reflect a congruence with the facial features seen on the Shroud of Turin, which adds to the discussion on how such images may have influenced the iconography of Christ in Christian art.

After the year 544, the image was relocated to the primary church in Edessa. Seventh-century accounts in the Acta Maris confirm its presence there, describing it as an acheiropoieta (a term for images not made by human hands) and referring to it as 'seddona', which is the Syriac translation of 'mandylion'. Additionally, in the same century, or perhaps earlier, the Acta Thaddaei depict the image as being folded into quarters.

The Byzantine Narratio and related sources, which document the transfer of the Mandylion from Edessa to Constantinople in 944, are the first to link the image with the events of Jesus’ passion, spanning from the Gethsemane to his Crucifixion and burial. The hypothesis that the image was first folded into four parts is believed to have originated around this time, possibly as a means of preservation or reverence, aligning with its increasing association with significant events from Jesus' life.

The public worship of the image in Edessa is corroborated by Smera, who refers to a depiction of Christ’s full image. In the 10th-century document, Codex Vossianus Latinus Q69, an account from the eighth or ninth century mentions that a canvas bearing the imprint of Christ’s entire body was preserved in a church in Edessa. This text, quoting Smera from Constantinople, narrates Abgar's desire to see Jesus. Jesus is said to have promised to send Abgar a linen cloth imprinted with not just his face, but his whole body, miraculously transformed: ‘linteum, in quo non solum faciei mee figuram, sed totius corporis mei figuram cernere poteris statum divinitus transformatum’. Jesus reportedly laid his entire body on a snow-white linen cloth, leaving imprints of both his glorious face and his noble entire body.

The text emphasizes the ‘whole body’ three times (totius corporis mei figuram; toto se corpore stravit; totius corporis status), indicating that the Edessan image depicted both Jesus's face and body, and was still present in the great church of Edessa: ‘Linteus adhuc vetustate temporis permanens incorruptus, in Mesopotamia Syrie apud Edissam civitatem in domo maioris ecclesie habetur repositus’. On certain feast days throughout the year, this linen was taken out of its golden box and displayed for all to see. It is not explicitly mentioned whether the linen was normally kept folded in the golden box and only unfolded for these occasions.

In 525, following the destruction of Edessa’s main cathedral in a significant flood, a new cathedral was completed about three decades later. Termed Hagia Sophia, akin to the renowned church in Constantinople, this cathedral was reputed for its stunning beauty, adorned with gold, glass, and marble, as noted by Segal in 1970. The 10th-century Greek "Liturgical Tractate", discovered by the eminent 19th-century historian Ernest von Dobschutz, reveals that this cathedral permitted only the Icon within its walls. The Icon was securely kept in a chest within a dedicated sanctuary, under the watch of an abbot, as detailed by Wilson in 1979.

A special procession took place on the Sunday before Lent began, where the Image, still enclosed in its chest, was paraded through the cathedral, accompanied by twelve bearers each of incense, torches, and flabella or liturgical fans, as Wilson described in 2000. Historian Robert Drews, analyzing the Tractate, inferred that the object in question was sizable, not a small, unframed cloth susceptible to the wind, as he noted in 1984. The chest housing the Icon was only opened by the archbishop, equipped with shutters that were seldom opened. On these rare occasions, the gathered crowd, including locals and pilgrims, could view it from a distance through a grille at the sanctuary’s entrance, though the face was difficult to discern. Von Dobschutz speculated that even then, the Icon was likely covered, as Scavone reported in 2001.

Wilson underscored the profound impact of these rituals, quoting the Tractate in 1979: the faithful were not permitted to approach or touch the holy likeness, nor to gaze directly upon it. This restriction heightened their divine fear, faith, and reverence for the revered object, making it more fearful and awe-inspiring. This aspect is critical for understanding the history of the Holy Image of Edessa and its challenging identification with the Shroud of Turin. The cloth was frequently kept folded and hidden, much like the Shroud was in later centuries in Turin.

https://www.shroud.com/pdfs/sn088Apr95.pdf

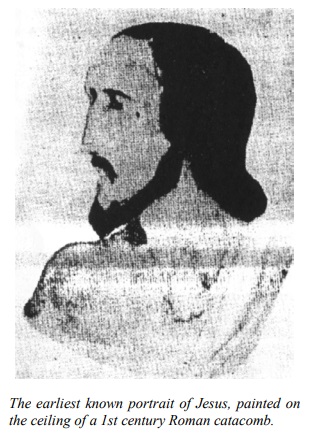

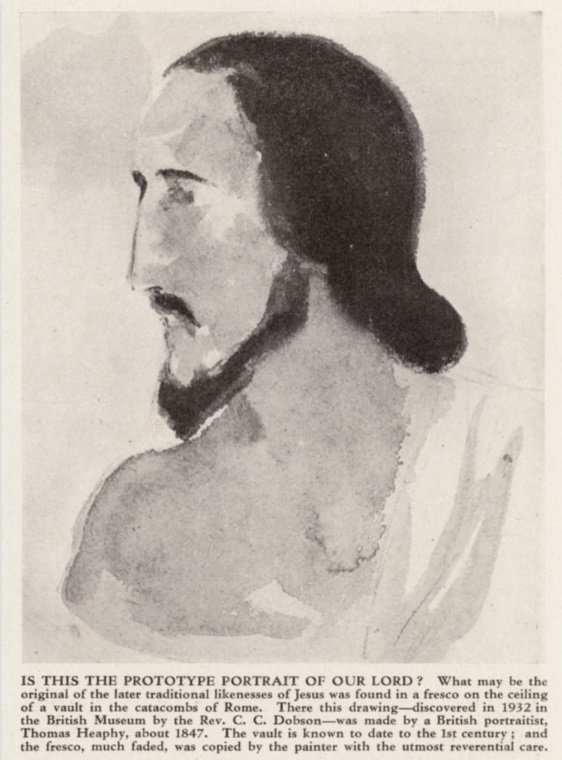

"IS THIS THE PROTOTYPE PORTRAIT OF OUR LORD? What may be the original of the later traditional likenesses of Jesus was found in a fresco on the ceiling of a vault in the catacombs of Rome. There this drawing—discovered in 1932 in the British Museum by the Rev. C. C. Dobson—was made by a British portraitist, Thomas Heaphy, about 1847. The vault is known to date to the 1st century; the fresco, much faded, was copied by the painter with the utmost reverential care."

The image is a drawing of Jesus Christ, made by a British portraitist named Thomas Heaphy in 1847. Heaphy was a prolific watercolour painter and a founding member of the Royal Society of British Artists. He primarily painted battle scenes and portraits of officers, such as the one he painted of Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington. The drawing was discovered in 1932 in the British Museum by the Rev. C. C. Dobson, who claimed that it was a copy of a fresco found in the ceiling of a vault in the catacombs of Rome. The vault is known to date to the 1st century AD; the fresco, much faded, was copied by Heaphy with the utmost reverential care. The fresco depicts Jesus Christ on a throne between two groups of apostles. It is one of several Christian frescoes that have been rediscovered inside the catacombs of St. Domitilla in Rome.

THE EARLIEST PORTRAIT OF CHRIST by Rex Morgan 1996

As long ago as 1985 my book The Holy Shroud and the Earliest Paintings of Christ was published. This dealt with my research into the work of a little known Victorian English painter, Thomas Heaphy, who had spent time in the Roman catacombs when they were being re-opened and explored by a number of archaeologists and art historians in the midnineteenth century. Heaphy's consuming interest was the received likeness of Christ which occurs again and again throughout the entire 2,000 year history of Christianity. He found a number of paintings of Christ in the catacombs and copied them with the aid of candlelight and a good deal of perseverance in extremely difficult conditions. His work was later published in the form of etchings taken from his original paintings and at the turn of the century other researchers expanded the theories Heaphy had put forward concerning the great antiquity of some of the paintings he had found. After his death a folio of Heaphy's original paintings was deposited in the British Museum Library (now the British Library) where they lay scarcely touched for more than a century. A few researchers during that time had sighted them, one or two of whom had published commentaries based on Heaphy's work. I came across them through a series of coincidences and became convinced that Heaphy had discovered and copied probably the earliest portrait of Christ ever painted and that it dated to the mid first century. My 1985 book and subsequent papers on the subject were regarded with hilarity, scorn and derision by several of our contemporary experts on art history. They stated that no painting in the Roman catacombs dates earlier than about the end of the third century and one went as far as to proclaim more than once that Heaphy was a fraud and that I had been fooled by his fraudulence. A chamber has been named the Orpheus Cubiculum on account of a painting of Orpheus which faces the observer as one enters the room. Indeed, this early painting of Christ on the ceiling of the Orpheus cubiculum in the secret depths of the Catacomb of Domitilla, well away from public access, was claimed to be a figment of Heaphy's imagination. This portrait shows a bearded, long haired Christ very similar to the image of the man on the Shroud and totally unlike all the early portraits of Christ for the first three centuries which depict him as a beardless Roman youth or in artistic inventions as the Good Shepherd. I have proposed the theory that if the portrait is very early then its remarkable similarity to that on the Shroud suggests that we have two likenesses of the same man: that in the catacomb probably painted by someone who had seen Christ in person or at the very least had from memory dictated and directed the painter who executed the work.

It was not until after I had published much of this that I came into contact with Sylvia Bogdanescu of London who had, quite independently of me, not only researched the work of Thomas Heaphy but had, in 1979, visited the Orpheus Cubiculum and had discovered and photographed the painting reported by Heaphy more than a hundred years before. Subsequently I took an expedition into the catacombs with Vatican permission in 1993 and took more photographs substantiating the work of Bogdanescu and giving the lie forever to fraudulence on Heaphy's part. This amazing portrait is still there, although somewhat damaged, and yet has never been published photographically in any known reference work including those which describe and illustrate the Cubiculum of Orpheus other than in Sylvia Bogdanescu's manuscript book and my paper given in Rome in 1993 about our joint research. My group currently cannot offer a cogent reason for this absence (or suppression) of publication unless it is that the authorities themselves realise that this may well be the earliest portrait of Christ and was executed in the first century by someone who had seen Christ and is therefore one of the most important artefacts in Christendom. One obviously does not want thousands of pilgrims tramping through the already severely damaged, deteriorating and dangerous catacombs to a "shrine" in the inner depths of those remarkable tunnels. It was an interesting coincidence that, three years after the Rome Symposium conducted by the French Shroud group CIELT, the proceedings of that congress were published. Indeed on the very day I was leaving Australia for London to discuss with Sylvia Bogdanescu our proposed May 1996 catacombs expedition I received a copy of the book containing the Rome papers including my New Evidence for the Earliest Portrait of Christ. Despite the omission of the bibliography, many typographical errors (not in the original text supplied to the editors) and despite one of my three coloured plates being inverted, the French editor has kindly seen fit in his French language summary to describe the work as "revealing sensational evidence which not only establishes certain catacomb paintings as First Century but that at least one has been influenced by the image on the Shroud (sic) and has probably been painted from direct observation of the man or instruction from an observer." The book is a magnificently produced 428 pages including many coloured plates on quality art paper. Now that the world can read the theories of Bogdanescu and Morgan we await the further comments and reactions of the experts.

In the meantime I led a further expedition in May 1996 into the Orpheus Cubiculum, again with gracious official permission. We have studied and assessed much of the work of Bogdanescu which provides an enormous amount of circumstantial historical evidence for the age of the tomb complex. We have found, for example, that all existing maps of that part of the catacombs have been based on inaccurate previous maps with inaccuracies and elisions perpetuated. Bogdanescu's return to original sources has shown without doubt that the assumptions on which many of the dating premisses have been based were quite inaccurate. In fact there was almost certainly an earlier entrance to the cubiculum complex, later abandoned and lost, which seems to place it in the middle of the First Century and has no relevance to the entrances or routes used today to access the cubiculum and its immediate environs. Further evidence for this comes from art expert Isabel Piczek who was a valuable team member in May 1996 and we await her further deliberations based on the extensive observations she made of pigments, colours and technique when we were in Orpheus this year. She has already concluded that the work in that cubiculum is probably first century. In the course of this year's observations when our team descended, armed with the most modern and non-harmful equipment, Christopher Morgan made the fullest series of serious photographs ever taken of the portrait and nearby paintings and environmental features including the use of infrared techniques. I made photographic and other observations in many of the nearby tunnels which C. Morgan has discovered converge at a now buried point where the original entrance probably existed and which has no relevance to the entrances used to gain access today or when the catacombs were rediscovered in the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries after being closed for a millennium. I should add that our work has already been supported by such well-known researchers as Marinelli, Whanger, Piczek, Scavone, Manton and others. Christopher Morgan's monumental Site Report is almost completed and I am privileged to have been invited to give another paper on the current research at the Shroud Symposium in Esopus, New York in August 1996. The outcome of all this is expected to be a new book based on the work of Bogdanescu, C. Morgan, R. Morgan and Piczek incorporating the fascinating data we have collected and the theories we have put forward. The conclusion is that we have exonerated the maligned Heaphy; we have discovered probably the earliest portrait of Christ in existence; it probably dates to mid first century; it was probably painted by a contemporary of Christ; it is almost identical to the man portrayed in the Shroud image and this adds to the claims for non-fraudulence of the Shroud of Turin.

https://www.shroud.com/pdfs/sn096Aug96.pdf

NEW EVIDENCE FOR THE EARLIEST PORTRAIT OF JESUS REX MORGAN

It is a three-quarters profile portrait of Christ, in a fresco medallion still faintly visible in the ceiling of a vault in the Orpheus Cubiculum* of the Domitilla catacomb. The figure has long hair and a beard; a white mantle is clasped upon the right shoulder. Just as Heaphy had copied it. There are catacombs below Rome containing paintings probably dating to the first century; that the portrait in the Orpheus Cubiculum could well be the work of an artist who had seen Christ or worked from a description by someone who had; that the features of the man in this profile "closely match those of the Man on the Shroud. ..."

https://www.shroud.com/pdfs/ssi42part10.pdf

The Domitilla Catacomb is one of the largest and oldest catacombs in Rome. The Orpheus Cubiculum, located within the Domitilla Catacombs in Rome, is part of an extensive underground Christian burial site that dates back to the 1st and 2nd century AD. These catacombs are named after Saint Domitilla, and they are among the oldest in Rome. The name "Orpheus Cubiculum" derives from a fresco within a particular chamber (cubiculum) that depicts Orpheus, a figure from Greek mythology, which is somewhat unique because it represents a pagan theme within a Christian burial site. The Orpheus motif was common in Roman art and was adopted by early Christians. In this context, Orpheus is often seen as a symbol of Christ due to the mythological Orpheus' ability to charm all living things and even stones with his music, which could be interpreted as a metaphor for Christ's message appealing to a wide audience. The specific age of the Orpheus Cubiculum within the Domitilla Catacombs is often estimated based on stylistic analysis of the art, the stratigraphy of the catacombs, and historical references to the Domitilla family and the early Christian community. It is widely accepted among scholars that the Domitilla Catacombs, including the Orpheus Cubiculum, were in use from the 2nd century, with expansions and further decorations possibly occurring in subsequent centuries.

The image makes it difficult to discern clear details that could give us a definitive representation of the figure depicted. Early Christian art often utilized a limited color palette due to the pigments available at the time. The colors seen in such frescoes were typically earthy tones, reds, ochres, and charcoals. While it's challenging to make out specific facial features from the provided image, many early depictions of Christ portray him with a serene expression, sometimes featuring large, expressive eyes which were a common stylistic choice in Roman art to convey the importance of the figure. It's a convention to depict Christ with shoulder-length hair and a beard, following the Judaic tradition of the time. The attire in such frescos usually includes a tunic and sometimes a mantle, reflecting the common dress of the period in the Roman Empire. Early Christian art was rich with symbolism. For instance, Christ was often depicted with a halo or an aura to signify divinity. Given the quality of the image, any reconstruction would be highly speculative. However, artists and forensic anthropologists sometimes attempt to reconstruct faces from historical depictions using these common elements, although such reconstructions are not definitive representations of historical figures but rather artistic interpretations based on available data and cultural contexts.

Stephen Jones: Thomas Frank Heaphy (1813-73) begins sketching the likenesses of Christ in the Catacombs of Rome which were early centuries' underground cemeteries. Heaphy was in Rome during the 19th century opening of many of the catacombs and sketched those that depicted the likeness of Christ, under conditions of great difficulty. Heaphy, relying on the datings of Italian archaeologist Giovanni Battista de Rossi (1822–94) who opened many of the Roman catacombs in Heaphy's day, thought that the likeness of Christ in the catacombs must have been first or second century when Christians were alive who had seen Jesus or knew Christians who had. Since Heaphy died in 1873, long before the 1898 first photograph of the Shroud [see above and "1898c" below], made the Shroud face well-known, Heaphy could not have been trying to, and nor did he claim to, depict the catacomb's face of Jesus as the face of the Shroud. Therefore, Heaphy's early centuries' paintings of Shroud-like images of Jesus' face in the catacombs are independent confirmation that the Shroud had existed from the first century. Leading Shroudies Ian Wilson and Dorothy Crispino (1916-2014) were critical of Heaphy, with Wilson accusing Heaphy of being "a cheat" and "fraudulent"[58]. But Rex Morgan had stood by Heaphy, that his catacomb paintings were evidence for the Shroud's existence in early centuries, while agreeing that Heaphy may have been wrong on some dates different, but nearby, Domitilla catacomb, which dates from the first century.

"The Earliest Portrait of Christ," A fresco dated to the 1st Century AD and having similar characteristics to the image on the Shroud of Turin and representing one of the most important recent pieces of evidence for the antiquity of the Shroud" (Photograph by Christopher Morgan 1996)[66]. This is not Bogdanescu's original photograph but a later one taken by Rex Morgan's archaeologist son, Christopher. I have ordered Bogdanescu's book, "The Catacombs and the Early Church" (1998) and I am hoping it has Bogdanescu's original photograph in colour. It does, but it is inferior to this photograph.]

Domitilla's husband was the consul Titus Flavius Clemens who was martyred in 95 and she herself was banished from Rome in the same year[69]. Wilson's response, instead of admitting that he had been wrong all along about Heaphy being dishonest, was:

"But even the most hardened counterfeiter (and I wouldn't rate Heaphy in quite that category), can pass the occasional genuine article"[70].

But would a "counterfeiter" have gone to this much trouble?:

"He [Heaphy] at once saw the value of the frescoes in this part, but his time in Rome was ended, and he must leave the next day. He realised that he could only do the work he desired in this section by staying all night, and he determined to do so. By further bribing he prevailed upon the custodian to lock up, and leave him there as if forgotten. Providing himself with candles and matches, as he thought sufficient, he descended 80 feet down to carry out his lonely and perilous task, - more perilous than would appear, for there have been instances of people swallowed up and lost in the catacombs, in one case that of a party consisting of an officer and twenty soldiers. As he proceeded he made careful notes of turnings and any features in the passages along which he groped his way, lest he should never find his way back to the entrance, so many and intricate are the passages in the larger catacombs. The catacombs are said to have an aggregate of 700 miles of passages, and a single false turn may lead into a labyrinth of passages from which the unwary explorer can find no way out. Having carefully noted in his sketch-book all the marks and turnings that he deemed necessary, he returned to the entrance to reassure himself that he knew his way. At length he was able to begin work, and soon became so absorbed that he forgot the novelty of his situation. There were three pictures he wished to copy, and having completed two [one of which was the above], he found that his supply of candles would not last out the work on the third, a picture of Adam and Eve in Paradise. Rather than lose his picture he decided to work while his last candle lasted, and then trust to groping his way back to the entrance to wait there in the dark until the door was opened. He tells us it became a race between his picture and the candle as to which would be completed first. The picture won by an inch of candle, and even this proved deceptive, for, as it turned out, afterwards, the wick did not extend above half-way into it. He ends his dramatic account of this adventure: `The perils I encountered during this night in the catacombs, in total darkness, and the difficulties I had to surmount in finding my way out, I must, however, leave to the imagination of the readers'"[71].

Image 2e

This particular portrayal of Jesus was heavily influenced by the cultural and artistic trends of the time, as well as the theological and philosophical beliefs of the early Christian church.

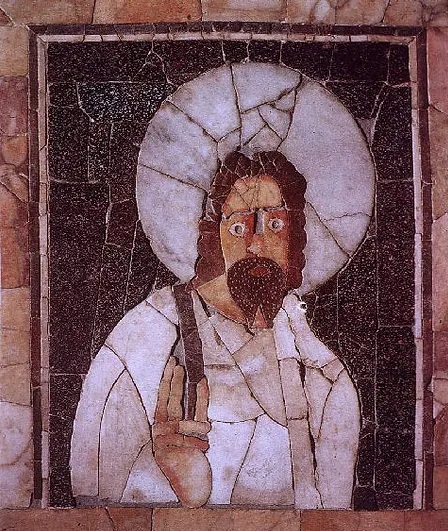

The images you've shared show various depictions of Jesus Christ from early Christian art, reflecting a range of styles and cultural influences. In these artworks, we see a blend of artistic trends from different periods and regions, which include:

Byzantine Influence: The golden backgrounds and the iconic, frontal poses are characteristic of Byzantine art. This style often imbued figures with a sense of divine presence and otherworldliness, which was in line with the theological emphasis on the divinity of Jesus. The halo around Jesus' head in these mosaics is a symbol of sanctity and has become a visual shorthand in art for holiness.

Roman Influence: Early Christian art was also influenced by Roman styles, especially in the realistic portrayal of figures and the use of narrative scenes. The adoption of Roman artistic conventions made the religious stories more accessible to the public, allowing the viewers to see the divine narrative unfold in a visual context they understood.

Philosophical and Theological Representations: These images also reflect the theological debates of the time. For instance, Jesus is often depicted as a teacher or shepherd, emphasizing his role as a guide and caretaker of humanity. This portrayal aligns with the Christian philosophical view of Jesus as the "logos" or the rational divine order of the universe.

Iconographic Development: The early Christian period was a time of significant iconographic development. The way Jesus is depicted in these artworks reflects the early church's search for a standardized representation of its central figure. Over time, these representations became more codified, and certain iconographic elements like the beard and long hair became standard in the portrayal of Christ.

Use of Symbols: In addition to representational art, early Christian iconography was rich in symbols. For example, the depiction of Jesus as the "Good Shepherd" with a sheep over his shoulders was an adaptation of a common pagan motif that was reinterpreted in a Christian context to symbolize Jesus' care for his followers.

Each of these images tells us not just about how Jesus was viewed at the time, but also about the broader cultural and artistic milieu in which these pieces were created. The synthesis of artistic styles and theological messages in these artworks illustrates how the early Christian church was both influenced by and sought to distinguish itself from the surrounding culture.

Image 2f

The depiction of Christ in the Hinton St Mary Mosaic in England from the 4th century AD presents Him as a conventional, beardless young man with a Hellenistic-Roman appearance.

The Hinton St Mary Mosaic is a particularly notable artifact because it reflects the early stages of Christian art and iconography, particularly in the Western part of the Roman Empire. The portrayal of Christ as a beardless young man is significant for several reasons:

Hellenistic Influence: The depiction of Christ in this mosaic shows clear Hellenistic influences, which were prevalent in the art of the Roman Empire. The Hellenistic style, developed in the Greek-speaking world after the conquests of Alexander the Great, emphasized naturalism and idealized forms. By portraying Christ in this manner, the artists were drawing on the visual language that was familiar and respected by the viewers of the time.

Roman Conventions: In the Roman context, youth was often associated with divinity and virtue. A beardless Christ would resonate with the Roman portrayal of gods and heroes as eternally young and idealized beings. This was a departure from the later, more widely recognized depiction of Christ with a beard, which emerged as a symbol of wisdom and maturity.

Transition from Paganism: The mosaic from Hinton St Mary also highlights the transitional period in which Christian iconography was still being defined and was heavily borrowing from the existing pagan imagery. This period of synthesis allowed for Christian themes to be depicted in a manner that was approachable to a population that was still largely pagan.

Christ as the Philosopher: The portrayal of a young, beardless Christ also aligns with the image of the philosopher, a prevalent figure in Greek and Roman culture. In this context, Christ is presented as the divine philosopher-king, a wise teacher whose authority comes from his spiritual insight rather than temporal power.

Didactic Purpose: Early Christian art often served a didactic purpose, teaching the stories and theology of Christianity to an illiterate population. By presenting Christ in a familiar form, the mosaic could communicate Christian beliefs within a visual framework understandable to a Roman audience.

Iconographic Evolution: The beardless Christ in the Hinton St Mary Mosaic is part of the iconographic evolution that would eventually lead to the standardization of Christian religious imagery. It represents a phase where artists were experimenting with how to best represent the central figure of their faith.

The Hinton St Mary Mosaic is thus a critical piece of evidence in understanding how early Christians saw themselves in relation to the dominant Roman culture and how they sought to express their understanding of Christ within that context.

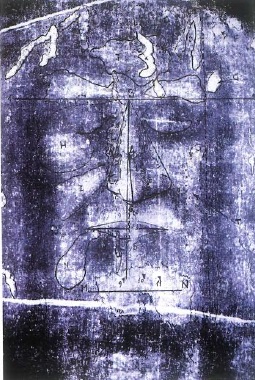

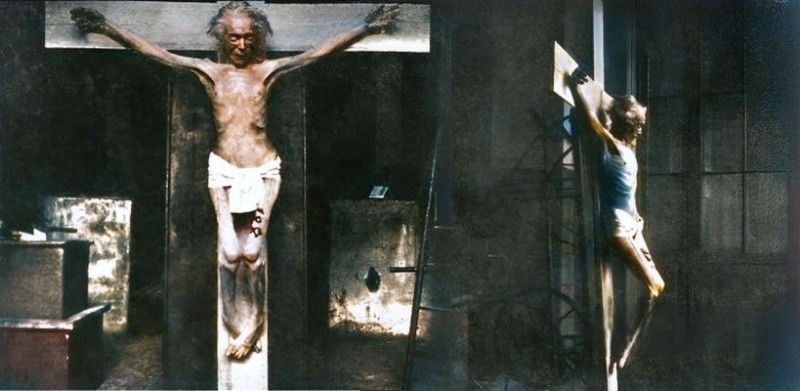

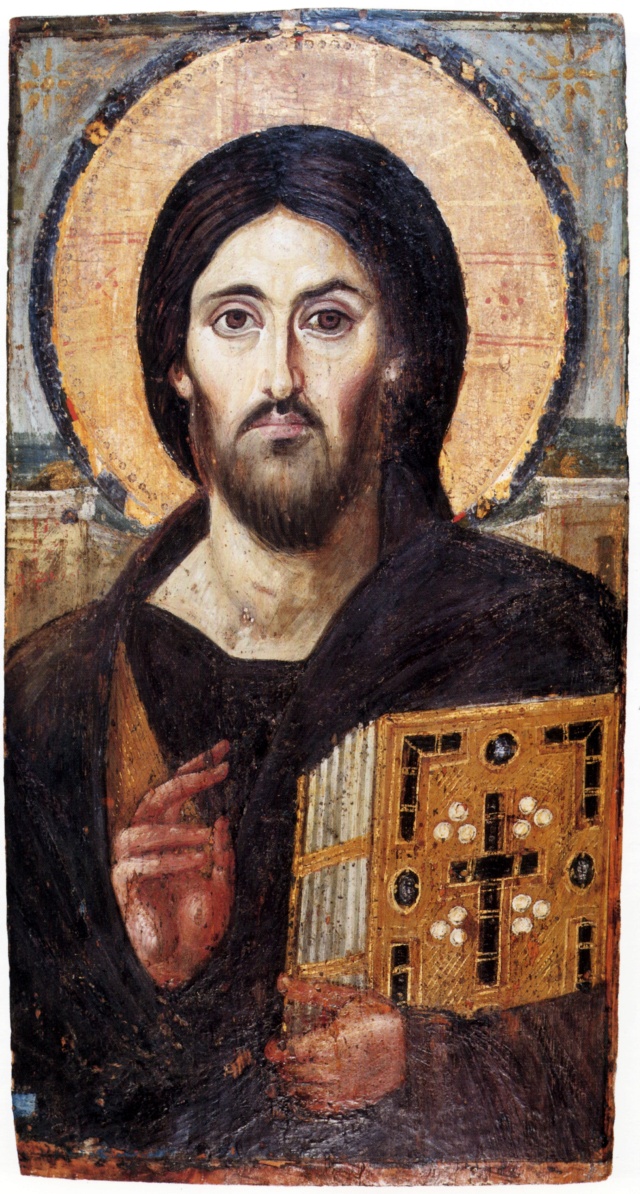

Christ Pantocrator ( God Almighty)

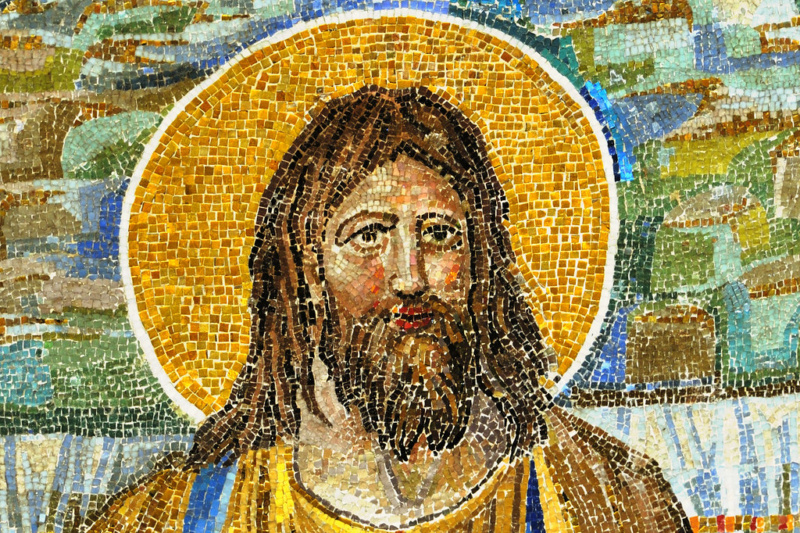

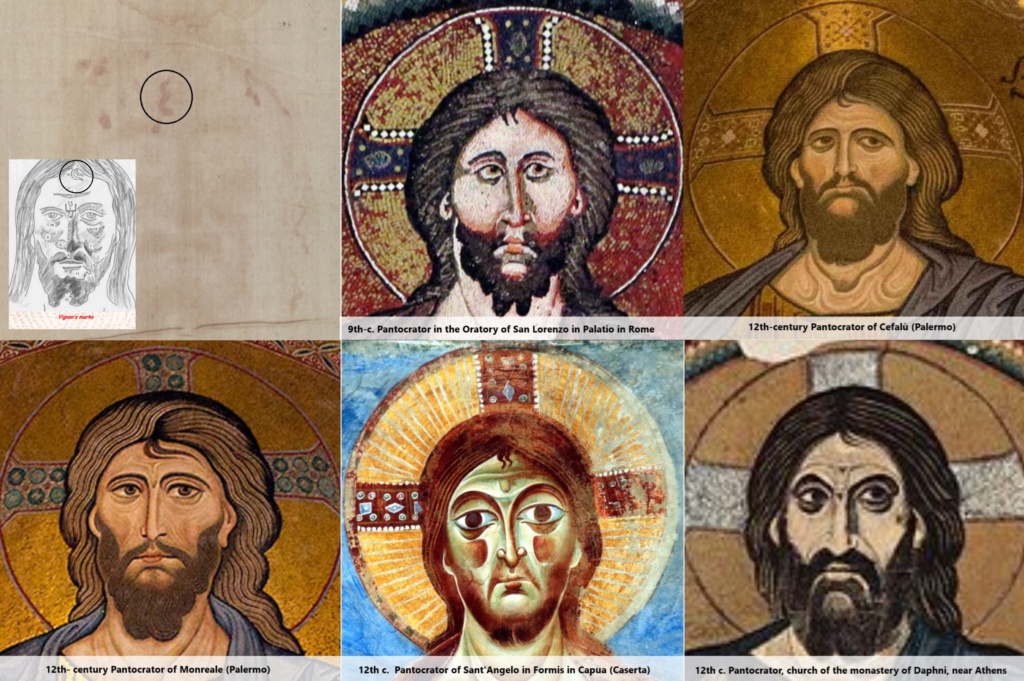

Image 2a

Pantocrator of Mount Sinai (6th century). The term "Pantocrator" (from Greek παντοκράτωρ) is a title that means "Almighty" or "All-Powerful," and is often used in Christian theology and art.

The icon was painted with the encaustic technique, depicting Christ with the two natures, divine and human, in his face. The New Interpreter’s Study Bible: “. . the Christ Pantocrator icon from Saint Catherine’s Monastery is by far the most accurate non-photographic representation of the Shroud image that we have seen.” 1

St. Catherine’s Pantocrator Icon: a good example of the new “true likeness” Christ face from the 6th century AD. When researcher Alan Whanger overlays the Shroud face on to this picture, over 250 points of similarity are observed.

If the Shroud were the new exemplar for the face of Christ, where was it and how did it so quickly influence Christian art from the 6th century? Wilson theorized that some unknown artist studied the Shroud face including Vignon’s peculiarities, made model drawings trying to incorporate each oddity, and then circulated copies to Christian communities engaged in religious decoration (Wilson 1979: 105). It probably began in the East, where some earlier art historians had recognized the important role played by the greater Syrian region in Christian art. O. M. Dalton observed “It was the Aramaeans [Syrians] who counted for most in the development of Christian art” compelling Hellenistic views to yield to Semitic modes of expression. This especially included “the cities of Edessa and Nisibis, where monastic theology flourished ...” (Dalton 1925: 24-25). This was an important key to their influence:

The East had always one advantage over its rival [Hellenistic West]... it was the home of monasticism, the great missionary force in Christendom .... Monks trained in the Aramaean theological schools of Edessa and Nisibis flocked to the religious houses so soon founded in numbers in Palestine. From the fifth century it was they who determined Christian iconography ... (Dalton 1925: 9).

The large pilgrim influx to the Holy Lands and migration of Syrian-trained monks to distant places ensured that what was current in the East would be known everywhere. “When we consider the part played by a monasticism trained in Aramaic theology, and the wide missionary activity of which Edessa was the base, the importance of the Syrian element in Christianity is at once realized” (Dalton 1925: 24). If there were an authoritative picture of Jesus to be found in the Syrian region, it is understandable how it could have become famous throughout Mediterranean Christianity. Although initially Wilson could not identify any contemporary documentary source for this new Jesus face, he recognized there was a likely candidate. In the 6th century a new class of icon was gaining prominence in the East, supposedly made by Christ himself and therefore acheiropoietos, “not made with (human) hands” (Wilson 1979: 111-112). The belief was that in one way or another they were imprints of Christ’s face. The most prominent was the Image of Edessa, the very picture Vignon had deduced as the earliest to exhibit the new “true likeness” features. Could the Image have been the Shroud? If so, why hadn’t anyone made that identification? Wilson soon noticed an obscure Greek word, tetradiplon, that proved to be the key to answering those questions. 2

The Pantocrator of Mount Sinai, dating back to the 6th century, is an extraordinary and iconic representation of Jesus Christ in Christian art. This depiction is housed in Saint Catherine's Monastery, located at the foot of Mount Sinai in Egypt, a site of immense religious and historical significance.

The term "Pantocrator" is derived from the Greek word παντοκράτωρ, meaning "Almighty" or "All-Powerful." In Christian theology, this title is used to emphasize the omnipotence of Christ, reflecting his divine nature as well as his role as judge and ruler of the universe. The Pantocrator icon is a central image in Eastern Orthodox Christianity, symbolizing the dual nature of Christ as both God and man.

In the Pantocrator of Mount Sinai, Christ is typically depicted in a frontal pose, holding the Gospels in his left hand while his right hand is raised in a gesture of blessing or teaching. This iconic image strikingly portrays the two natures of Christ: his humanity and divinity. The facial features often exhibit this duality; one side of the face may appear gentle and compassionate, representing the human nature of Christ, while the other side appears more stern and powerful, symbolizing his divine nature.

The technique used in this icon is encaustic painting, an ancient method where colored pigments are mixed with hot wax and applied to a surface. This technique was widely used in the Eastern Roman Empire, and its durability has allowed many encaustic works, like the Pantocrator of Mount Sinai, to survive in remarkably good condition. The encaustic method gives the icon a unique texture and depth, contributing to its striking and enduring visual impact.

Last edited by Otangelo on Fri Jan 26, 2024 10:28 am; edited 53 times in total