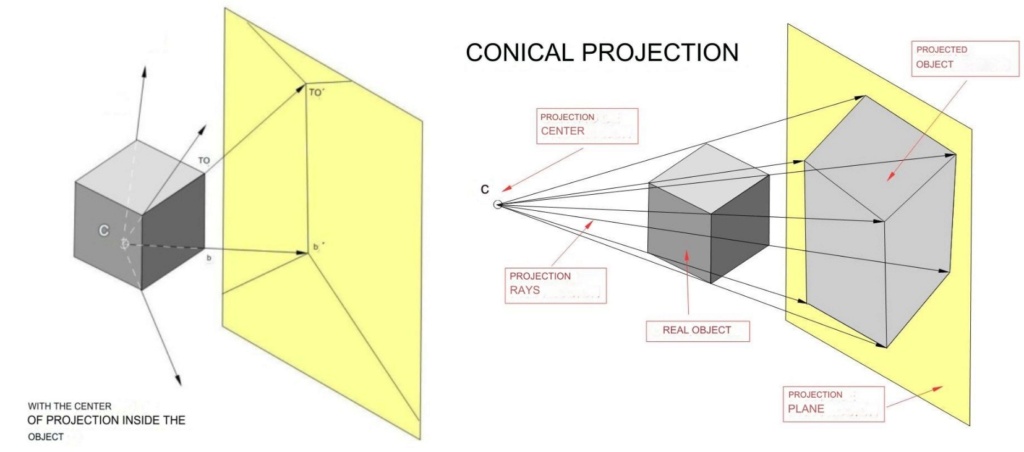

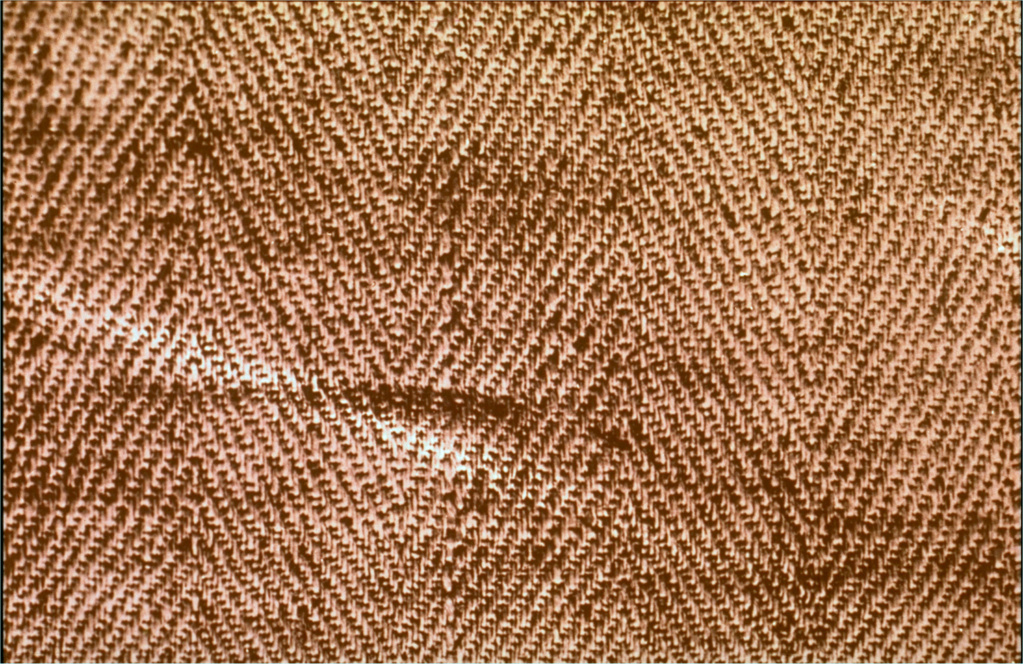

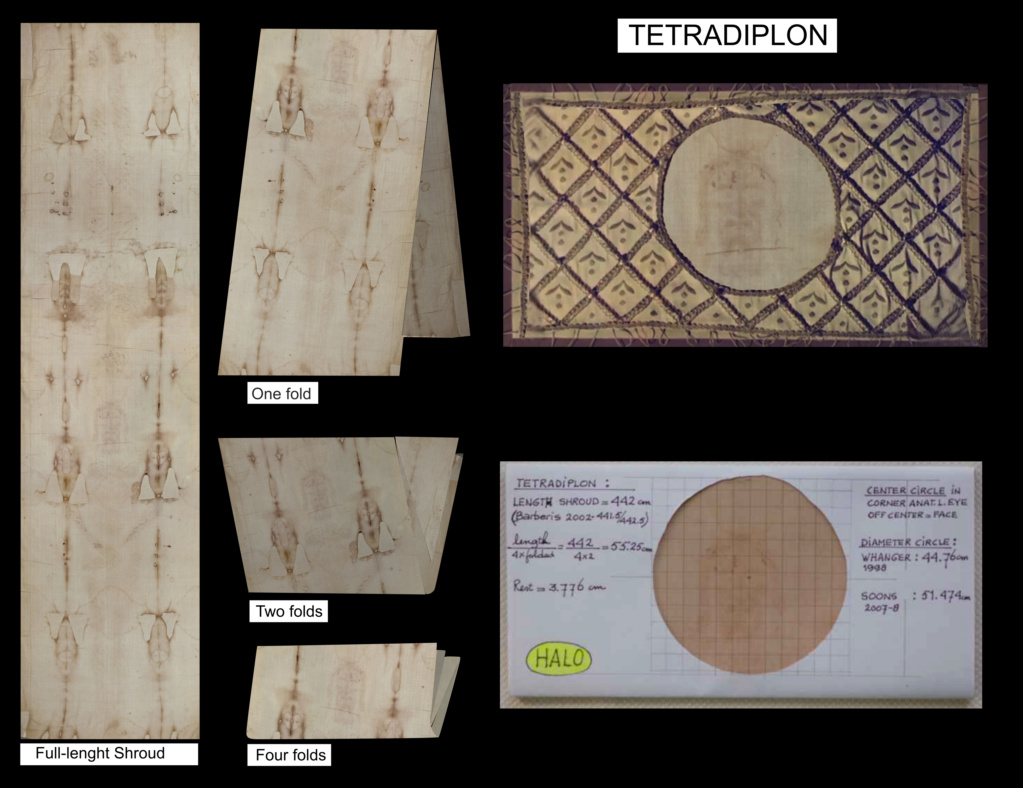

In examining the various terms associated with the Image of Edessa, one particularly significant Greek word stands out: 'tetradiplon', used exclusively in Greek literature to describe this image. Its unique application indicates a distinct characteristic of the Image, setting it apart from other depictions of Christ. Surprisingly, modern historians have largely overlooked the importance of this term and its implications, which might challenge prevailing assumptions about the Image. Understanding 'tetradiplon' is not straightforward, despite its apparent simplicity. The word combines the elements for "four" and "fold over in two." However, it's unclear whether this implies the cloth was folded over twice to create four layers, folded in four to make eight layers (four double layers), or folded in a manner resulting in sixteen layers. Since 'tetradiplon' is uniquely associated with the Image of Edessa and no comparative object exists, deciphering its exact meaning is challenging. The term 'diplon', meaning folded in two, creates two layers. However, there are no similar numerical terms like 'triplon' or 'hexaplon'. Words like 'diploos' mean double, and 'hexaploos' means six times larger, but these don't provide a clear comparison for 'tetradiplon'. If 'diplon' signifies two layers, 'tetradiplon' could imply either sixteen layers (folded over twice four times) or eight layers (four double layers achieved through three folds). However, there's a method of folding a large cloth involving four actions to achieve four double layers: first folding it in half, then in quarters three times. The exclusive use of 'tetradiplon' for the Image of Edessa signifies its significance in understanding the cloth's appearance. If the Image was folded multiple times, it couldn't have been imprinted onto a solid surface like wood. The term suggests the cloth was reasonably large, larger than what would be required for just a facial image. This inference, supported by John Damascene's description of it as 'himatión' (a large piece of cloth), is a crucial yet often overlooked point in understanding the nature of the Image of Edessa.

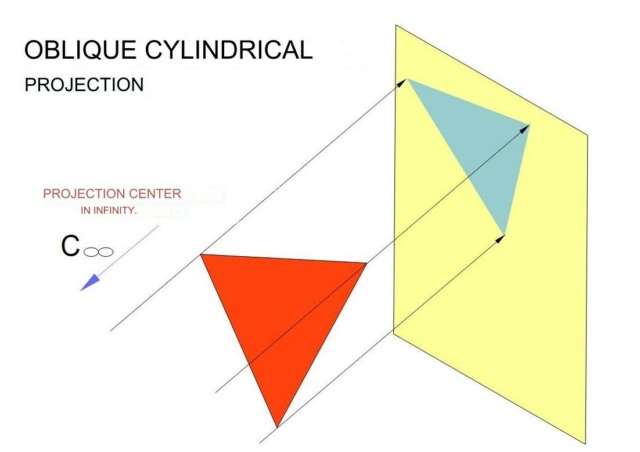

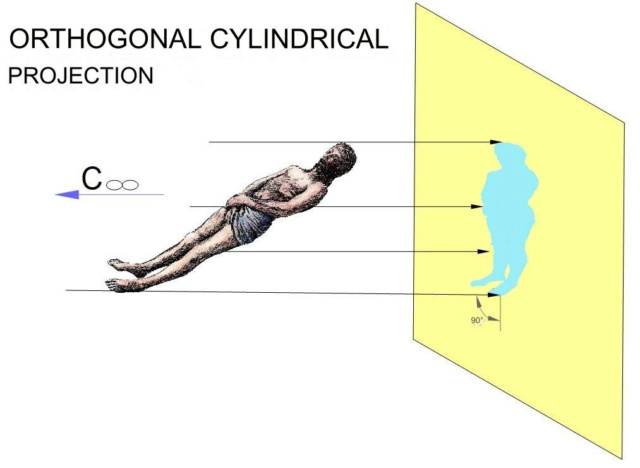

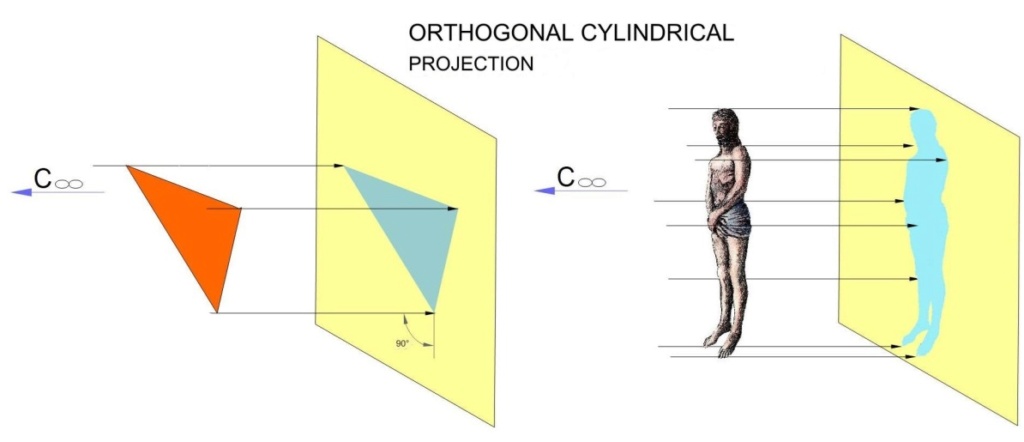

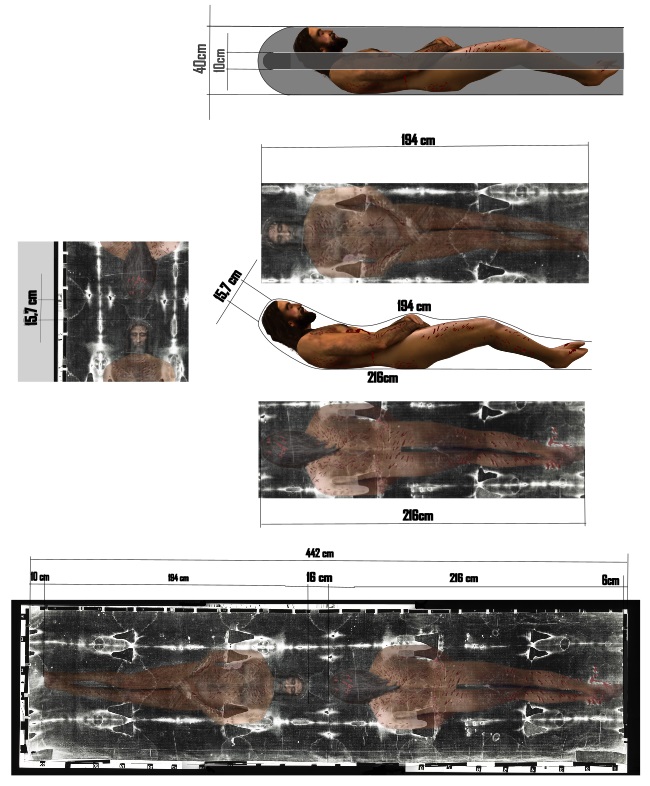

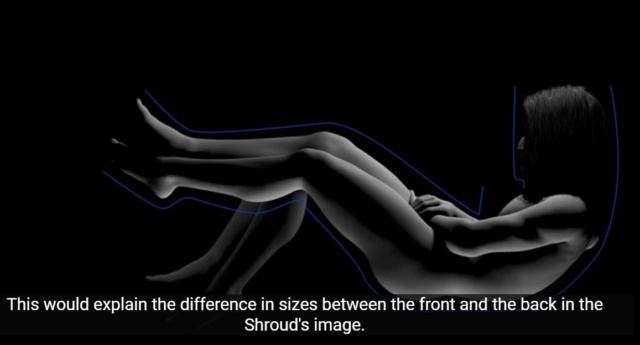

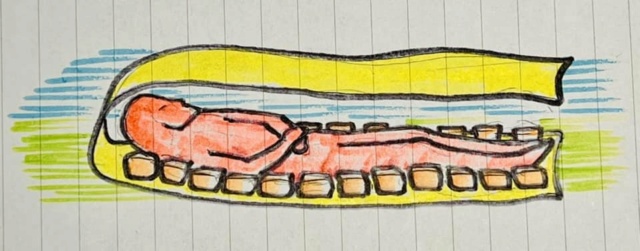

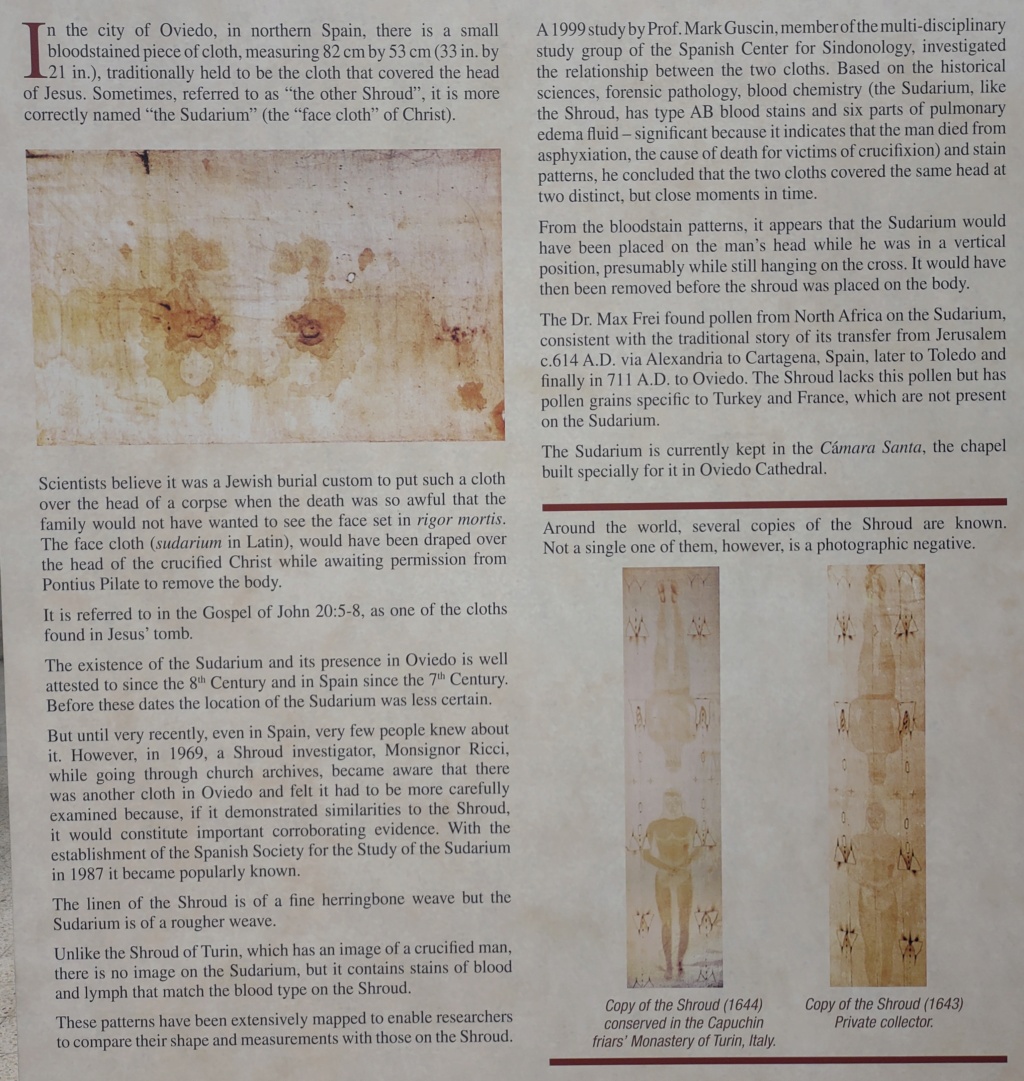

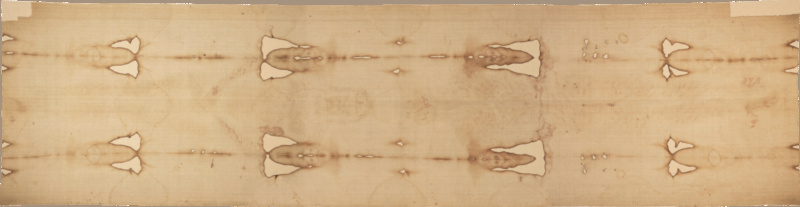

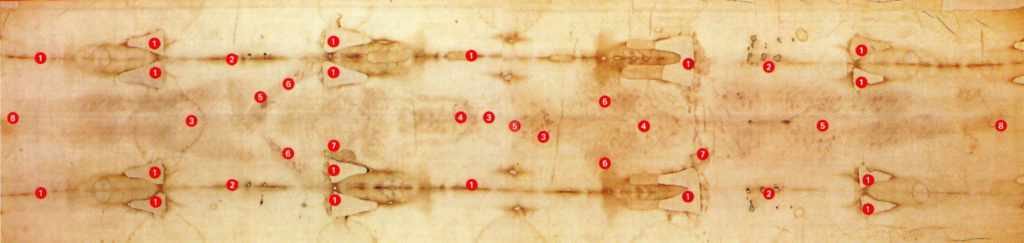

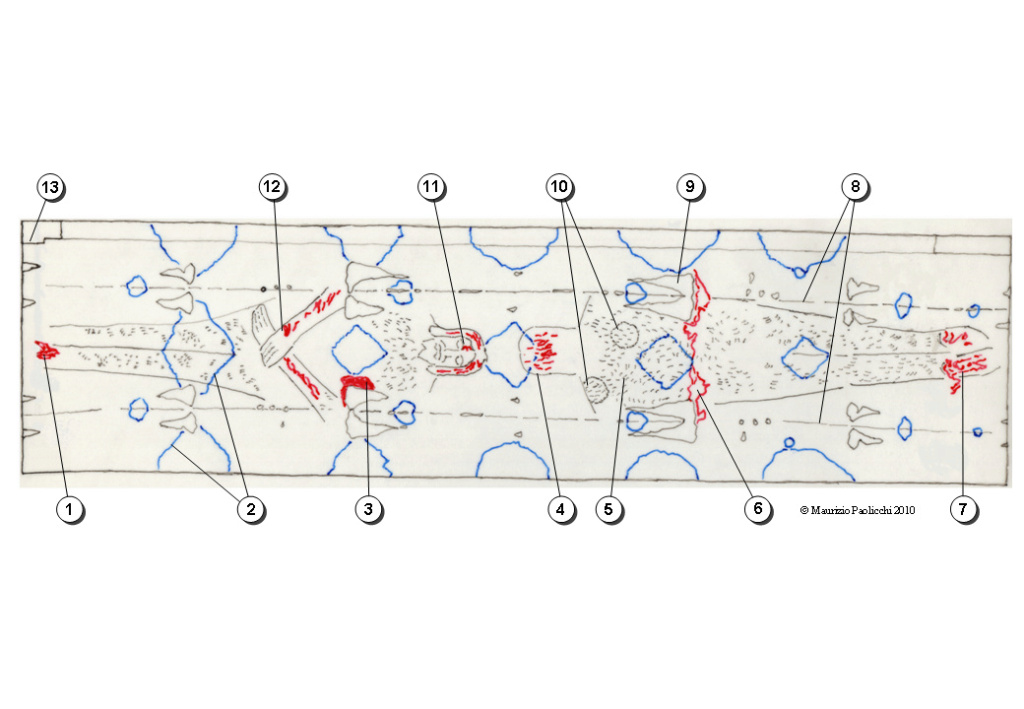

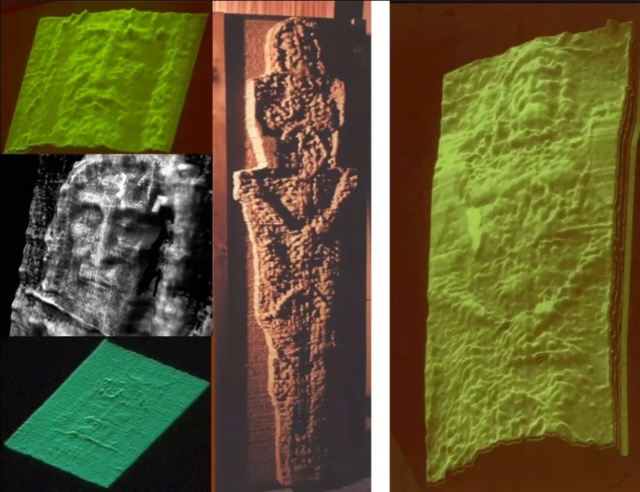

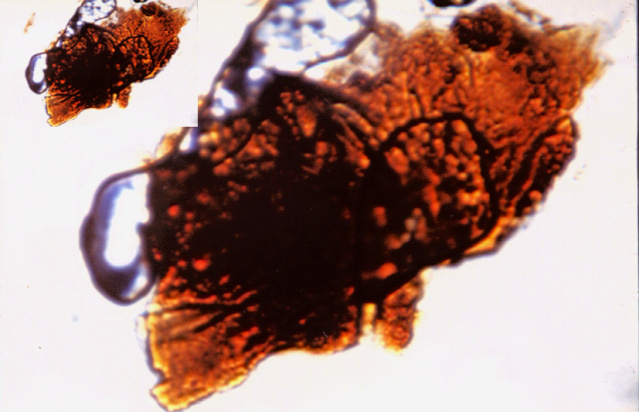

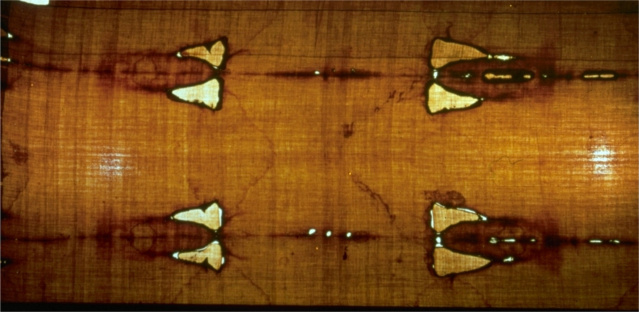

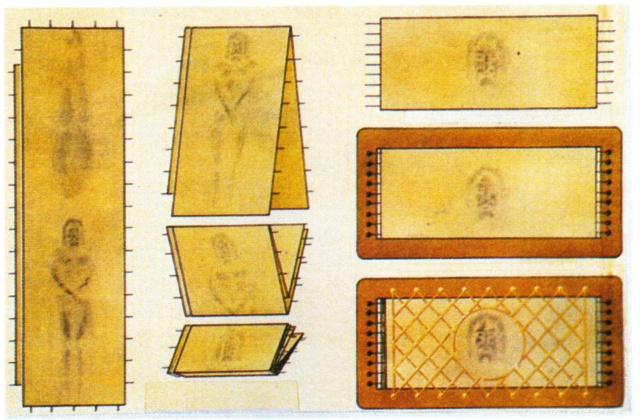

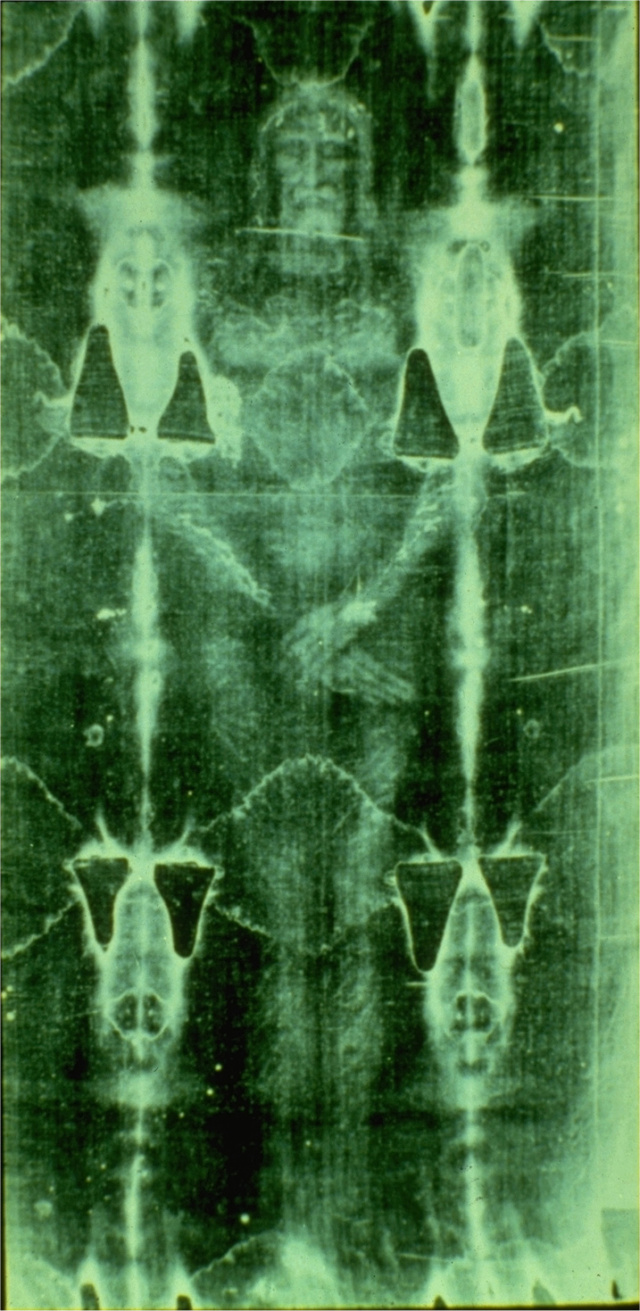

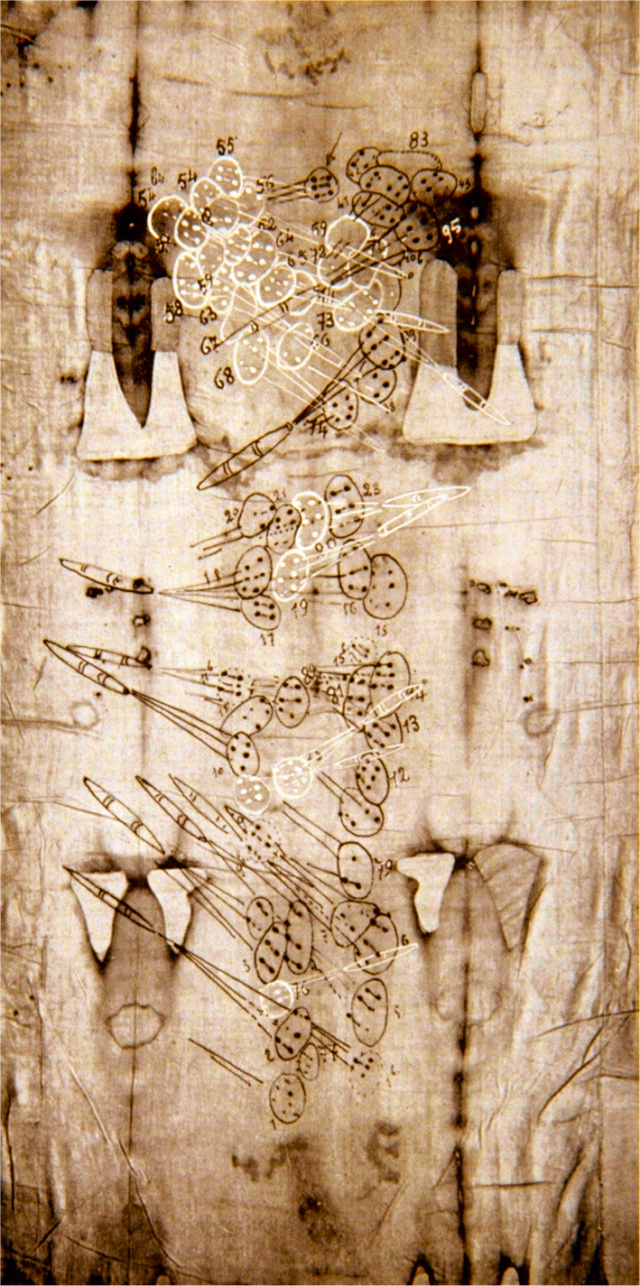

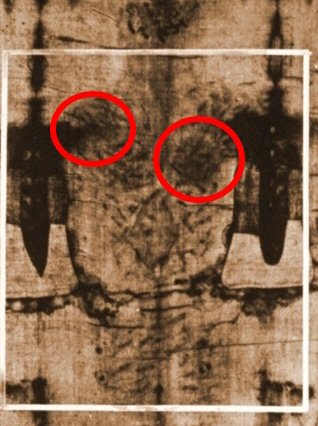

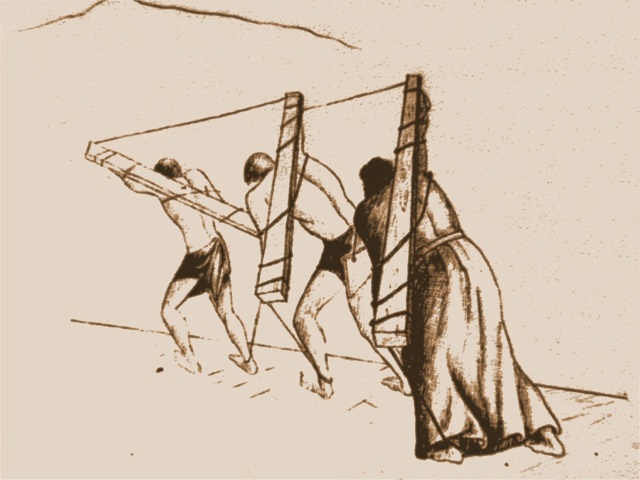

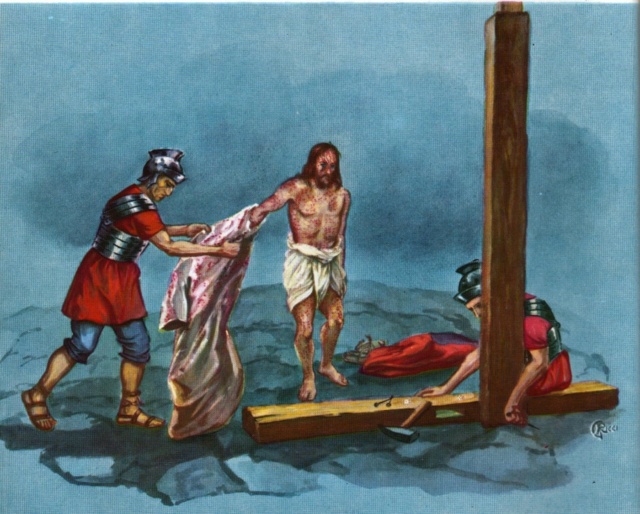

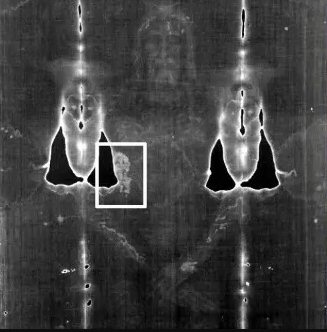

In the "Acts of Thaddaeus," as well as in texts derived from it, the cloth associated with Jesus is referred to as τετράδιπλον. A translation from 1978 notes that τετράδιπλον literally means "folded in four." Building on this detail, there's a hypothesis suggesting that the image from Edessa and the Shroud of Turin might be one and the same. This theory posits that if the Shroud were folded four times, it would display only the head and upper torso of the figure depicted. As a result, it is conjectured that observers might perceive it merely as a smaller cloth imprinted with the face of Jesus, not realizing that a full body image was concealed within the layers.

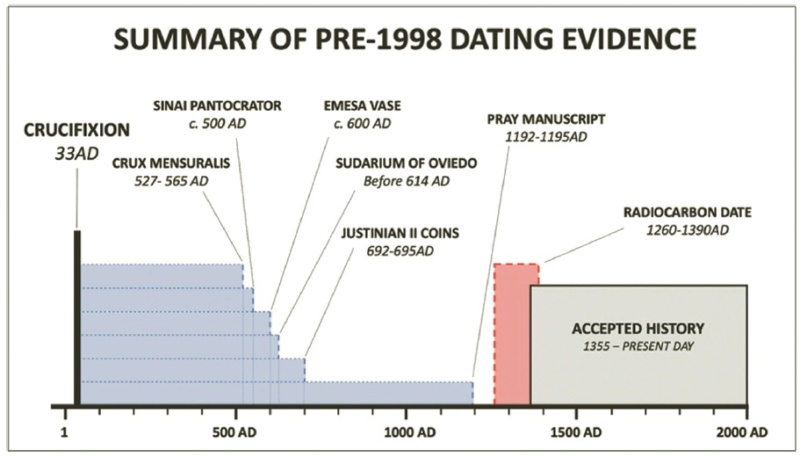

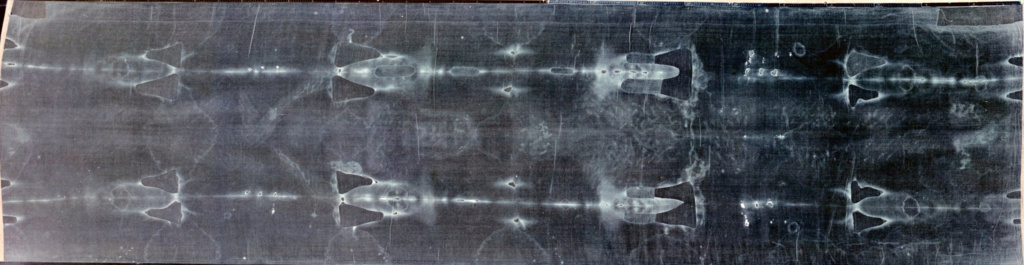

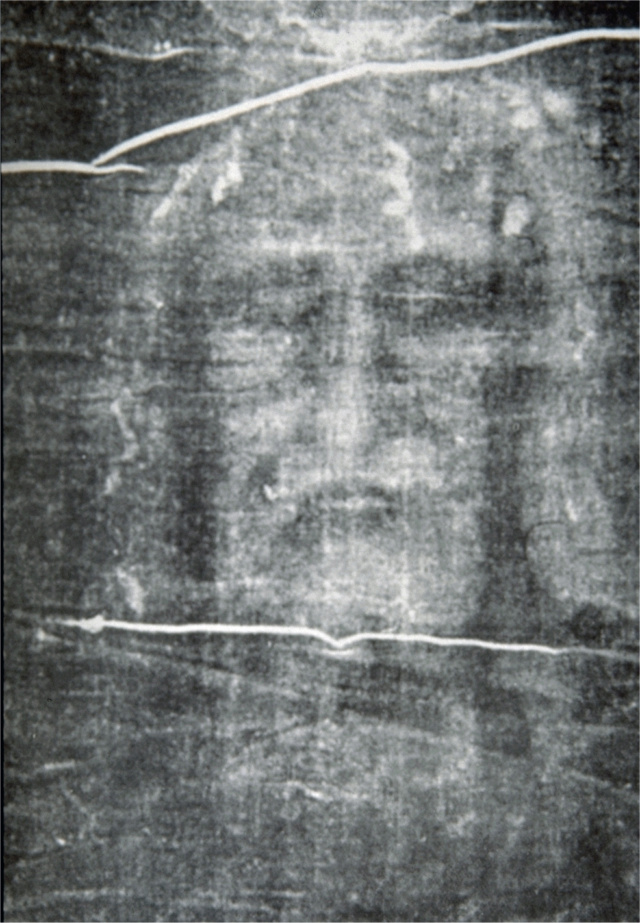

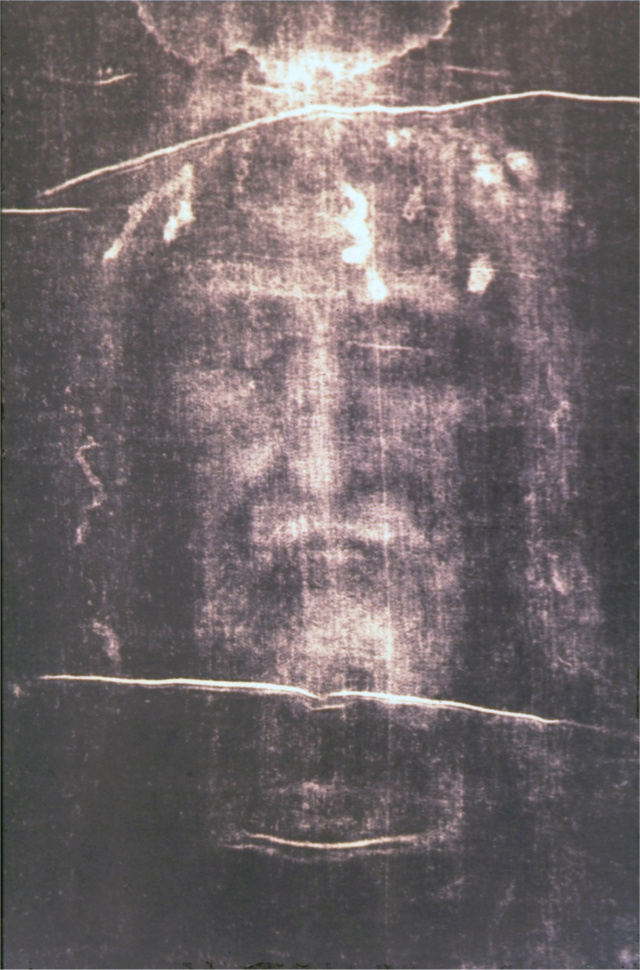

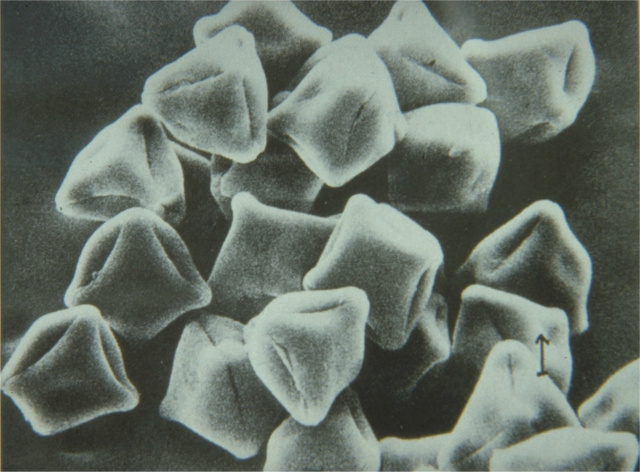

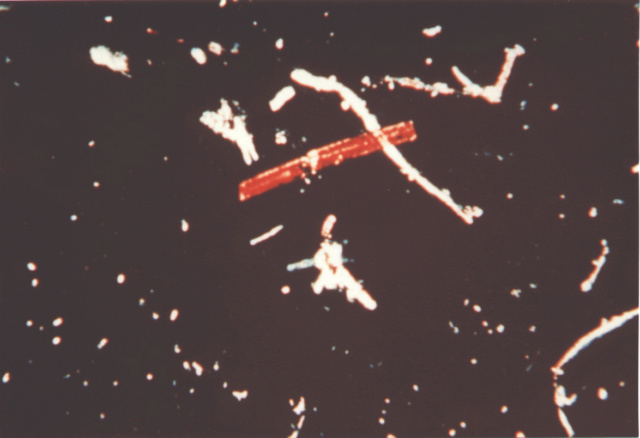

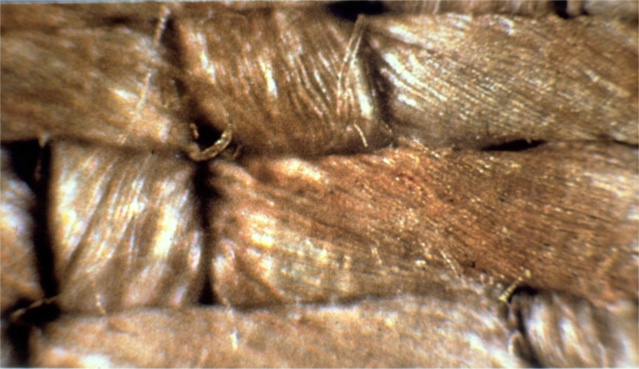

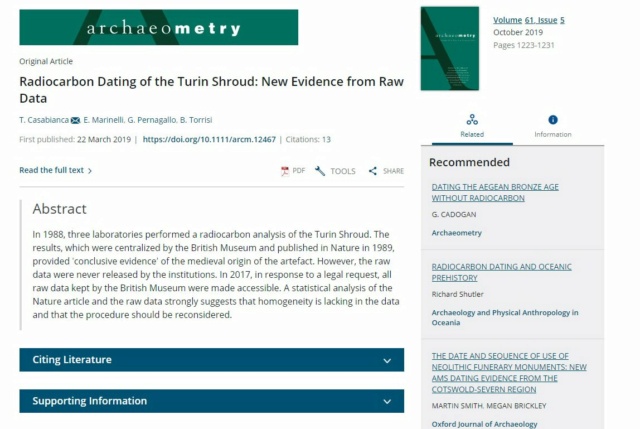

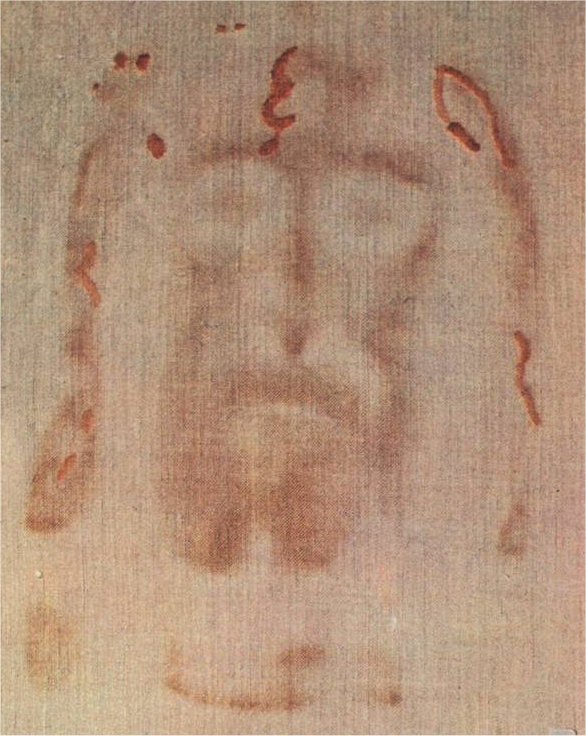

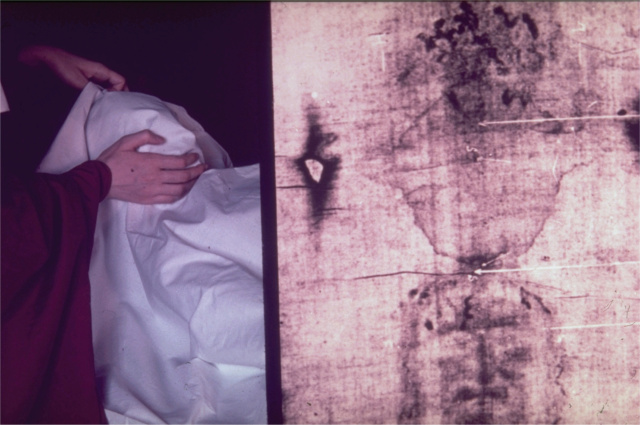

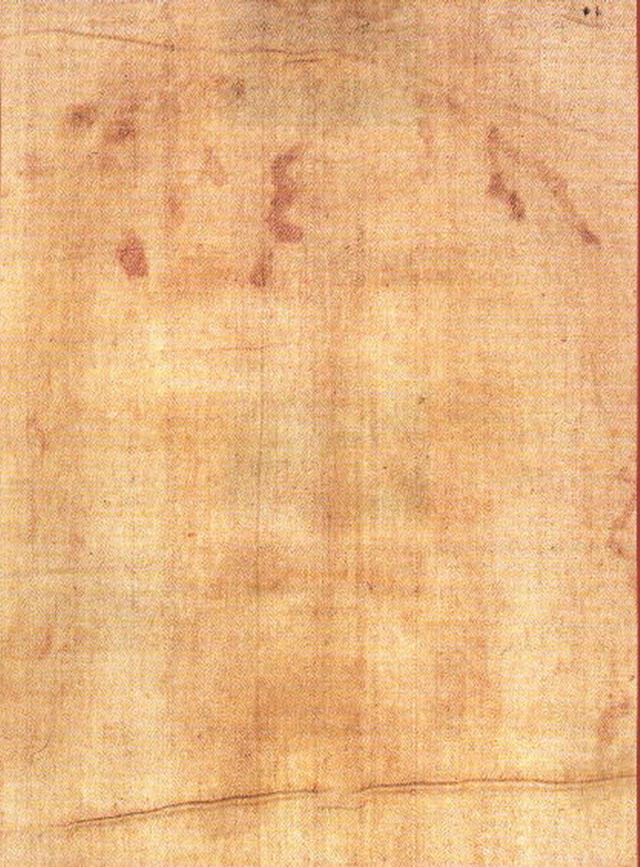

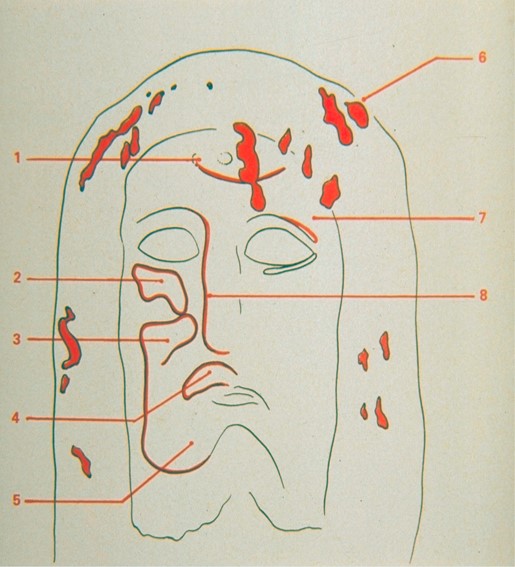

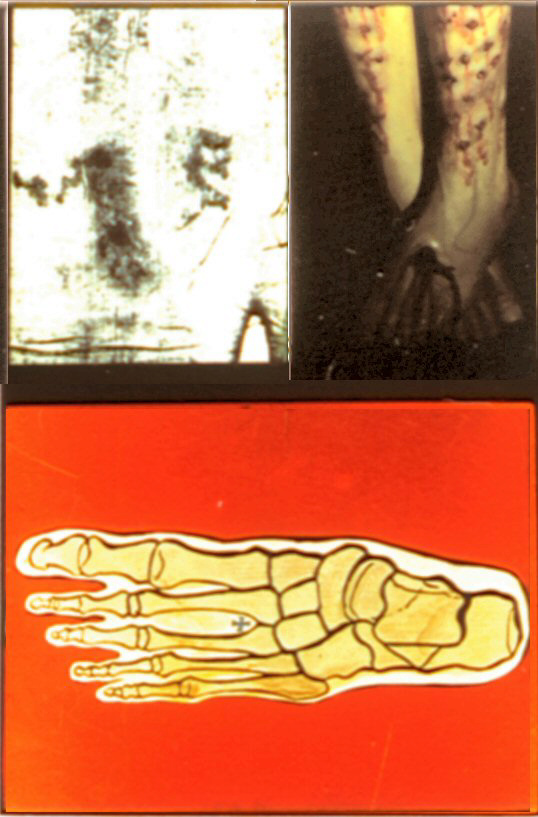

Petrus Soons: he HALO that has been discovered in a variety of photographs and that fits the size of the round opening in the TETRADIPLON, showing only the head of the Man on the Shroud, is a very strong indication that IAN WILSON’s theory that the Shroud of Turin and the Cloth of Edessa (Tetradiplon, Mandylion) are identical is true. Because there is no anatomical detail visible of the surface of the body in the region of the upper thorax of the image of the Man on the Shroud, the head looks like disembodied and floating. That was probably the reason that for many centuries people did not know and realize that this cloth contained the image of the whole front and back of the body, apart from the fact that the TETRADIPLON was mounted, framed and covered with a precious cloth, leaving the round opening showing the face only. This object was considered so sacred that very few people were permitted to even touch or see it. This discovery means also that we can date the Shroud of Turin to at least the year 525 A.D. when the Cloth of Edessa was rediscovered in the niche above the city gate.This would also prove that the sample that was taken from the Shroud for the Radiocarbon Dating of 1988 was not representative for the whole Shroud.

TWO OTHER DETAILS VISIBLE IN AND AROUND THE HALO THAT WE WILL FIND BACK IN BYZANTINE ART

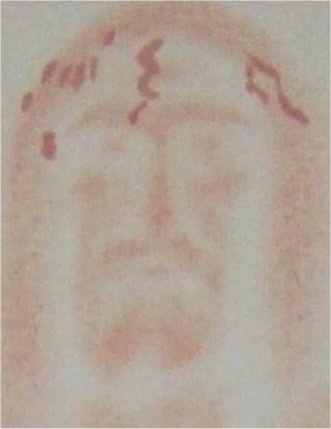

When you take a good size photograph of the whole Shroud and double it in four you will find on one side the image of the face only. Reconstructing what the Byzantine artist did in the past when framing the image and finding the center of the circle around the head, you will first make a vertical line in the middle of the cloth and then make a horizontal line crossing both eyes. (artistically spoken the center of the face is between both eyes). Where the vertical and horizontal line cross you will find the center that you need to construct the circle to create the round opening in the covering precious cloth to make the face visible. Now we have the round opening in the middle of the cloth. If you do that you will find that the center of the circle will end up IN THE CORNER OF THE RIGHT EYE. The reason for this is that the image of the Man on the Shroud is not exactly in the middle of the cloth but displaced about 2-3 cm to the left side of the median line.

The measurements of the Mandylion are 113 cm x 55.2 cm, when the cloth is “doubled in four”. A second observation is that the border of the covering on the top of our HALO is smaller than the border on the bottom of the Halo. The diameter of the HALO was measured by me to be about 48 cm.

https://shroud3d.com/research-on-the-3d-materials/research-halo-around-the-head/

Acheiropoietos

Another term often associated with the Image of Edessa is 'acheiropoietos', meaning 'not made by human hands'. This term is notably absent in the Septuagint (LXX), likely due to the absence of an equivalent Hebrew word. The positive form 'cheiropoietos' appears in contexts like Isaiah 2:18, where it is used to mock the statues of false gods, described as human-made. In the New Testament, the concept of 'acheiropoietos' emerges as a distinctly Christian idea. Mark 14:58 contrasts a human-built temple with a spiritual temple that Christ would establish, and 2 Corinthians 5:1 and Colossians 2:11 use the term to describe heavenly dwellings and spiritual circumcision, contrasting them with their earthly, human-made counterparts. The adjective 'acheiropoietos' wouldn't apply to an obviously painted icon. Yet, in the earliest account of the Image's origin in the Doctrine of Addai, dating around AD 400, it is explicitly stated that Hanan, the king's archivist and artist, painted Jesus’ portrait. This account gives no indication of a miraculous origin for the Image. This description raises questions about whether the author had seen the Image and, if it was indeed a painting, why later versions diverge so significantly. Subsequent narratives uniformly assert that the Image was not a painting but an 'acheiropoietos' – an image not made by human hands. Interestingly, some copies of the Narratio de imagine Edessena on Mount Athos show uncertainty about this. When referring to Abgar's belief in the Image on the cloth, the text suggests that it might be a painted image, although in first-hand texts from Megistes Lavras and Iveron, the negative ('not') appears to be a later addition. Megistes Lavras 644 and von Dobschütz's version omit the negative, implying that the Image is a painting. However, considering the overall context of these manuscripts, this is likely a copyist's error, later corrected to maintain consistency with the general understanding that the Image was an 'acheiropoietos'.

Regardless of the actual nature of the Image of Edessa, it was most likely not a painting, and therefore, a non-human creation. This viewpoint aligns with the chosen terminology in the text, emphasizing the Image's divine origin.

Michael Whitby introduces a compelling theory about the origin of the term 'acheiropoietos' as applied to the Image of Edessa. He refers to Procopius, who describes a Persian mound in Edessa that was set ablaze with divine assistance, attributed to the Image, as 'heiros kheirpoiētos'. The use of this term, implying divine intervention, eventually became associated with the Image itself. Hans Belting, however, considers the term 'acheiropoietos' overly complex and contradictory. He argues that an image not made by human hands paradoxically implies it is not an image at all but the actual body. This interpretation, however, seems to diverge significantly from the intentions of the authors who described the Image of Edessa as 'acheiropoietos'. Their description implies a miraculous creation of the Image through divine power, not a human-made painting. Andrew of Crete (circa 660-740 AD) further clarifies this concept, explicitly stating that the Image of Edessa was not a painting: "First of all, the sacred image of our Lord Jesus Christ that was sent to Abgar the ruler, which is an imprint of his bodily form and owes nothing at all to work with paint..." This statement strongly supports the notion that the Image was a miraculous imprint of Christ's form, distinct from any painted representation.

Mandylion

The term "Mandylion" became prevalent when the Image of Edessa was brought to Constantinople. Theories about the origin of this word vary, with many suggesting a link to the Arabic 'mandil'. However, it seems almost implausible to disregard the influence of similar words in various languages: Greek 'mantilion' and 'mandalion', Latin 'mantilium', Aramaic 'mantila', and late Greek 'mandikē'. These terms typically refer to a large cloth, like a monk's mantle or a tablecloth. Another term often associated with the image on the cloth is 'morphē'. This word is central to the discussion in Philippians 2:6-7-8, where it is debated whether it implies that Jesus was equal to God or, as Adam was made in the image ('eikōn') of God, Jesus was less than God. Other words used to describe the Image of Edessa include 'sindon' (linen cloth), 'eikōn' (image), 'sudarium' (John Damascene, the Letter of the Three Patriarchs), 'ptukhion' (Leo the Deacon), and 'epi tō prosōpō' (on the face). However, none of these terms provide additional clarity about the precise nature of the Image of Edessa.

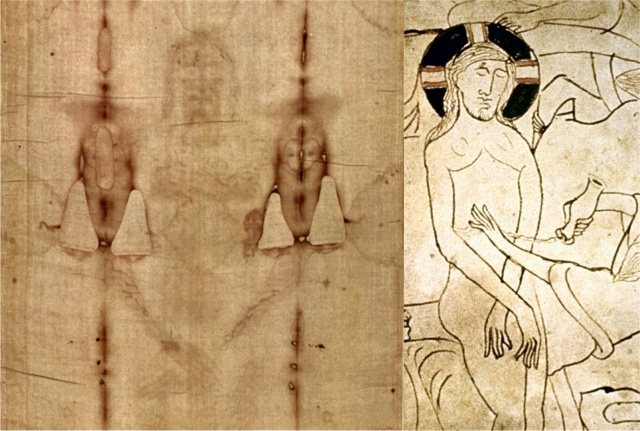

A full-body image

In his "Historia Ecclesiastica," Ordericus Vitalis provides a somewhat perplexing account of the image Christ sent to Abgar: Abgar, the ruler of Edessa, received a sacred letter from Lord Jesus, along with a precious linen cloth. Jesus had used this cloth to wipe the sweat from his face, and on this cloth, the image of the Savior was miraculously imprinted, shining forth. This image astonishingly revealed both the form and the size of the Lord's body to all who beheld it. At first glance, the description suggests that the image on the cloth should only be of Jesus' face, as that was what he wiped with it. However, Vitalis then indicates that viewers of the cloth could see an image of the entire body of the Lord. This appears contradictory: how could a cloth used to wipe Jesus' face display an image of his full body? Yet, such contradictions were not uncommon among writers of that era, who often seemed less concerned with consistency than contemporary authors might be. The narrative surrounding the Image of Edessa evolved over time, adapting and expanding as new contexts emerged. The various attributes of the Image, as described in different documents, were likely adaptations to suit specific circumstances rather than discoveries of inherent qualities of the Image itself. Understanding what might prompt authors to describe the Image as a full-body representation is challenging unless such a portrayal was based on the actual appearance of the Image. Each new generation reinterprets and transforms texts, blending past and present. This approach implies that modifications to the text, including changes in details, reflect more about the beliefs of the readers or listeners than the original author's intentions. In the case of a tangible object like the Image of Edessa, later additions or observations could be more accurate than earlier accounts, particularly if they are based on direct eyewitness evidence rather than mere hearsay. These later accounts might correct earlier misunderstandings. It is clear that definitive conclusions about the origins of the Image of Edessa are elusive. The exact timing of its first mention in historical records is uncertain, as is the period of its actual creation. There exists a longstanding tradition that the Image was hidden and rediscovered centuries later. Its association with Christ and the assertion that it was not made by human hands were not crucial for establishing its ancient connection to Christianity in Edessa.

The letter attributed to Christ and the dispatch of a disciple named Thaddaeus or Addai was a more explicit way of suggesting that Christianity had deep roots in Edessa from early times. However, such traditions need to be critically examined for additional evidence. The diverse and often contradictory conclusions drawn by researchers about the origins of the Image of Edessa highlight the uncertainty surrounding its emergence. Regarding the nature and appearance of the Image, it is widely believed, based on various accounts, to have been a linen cloth bearing the face of Jesus. This depiction is consistent with the most popular legend, in which Jesus, during Ananias's visit, presses a cloth to his face and sends it back to Abgar. This version suggests that the Image was a miraculous facial imprint of Christ made during his lifetime. However, the narrative becomes more complex. A different account, emerging around the tenth century, speaks of a cloth pressed to Jesus's face during his agony in the Garden of Gethsemane. This version appears in Gregory Referendarius' sermon when the Image was moved from Edessa to Constantinople. The "Narratio de imagine Edessena" presents both the Gethsemane and Ananias versions, indicating a hesitance to forsake the traditional account while acknowledging the newer one. The author admits the existence of two versions without endorsing either as definitive.

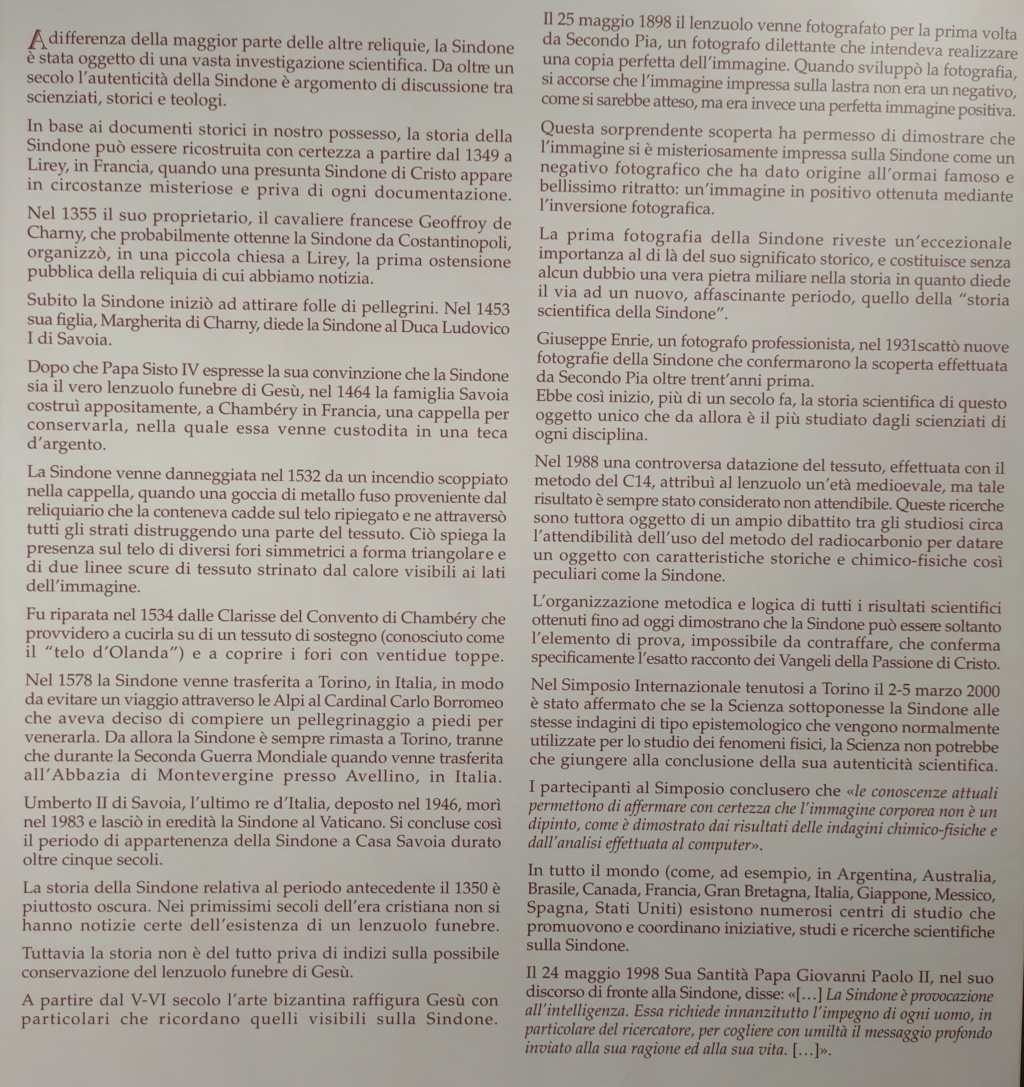

During the 8th through 10th centuries, additional evidence suggests that this is a large, folded cloth depicting Christ's full, bloodied body.

The 8th through mid-10th centuries were to make the Holy Image of Edessa the most famous icon in the Christian world, offer clues as to its physical appearance, but also reflect predictable contradictions stemming from the great secrecy in which it was kept. John of Damascus (d. 749), a defender of image veneration, wrote “he [Jesus] took a cloth (rakos) and applied it to his face and impressed on it his own likeness (charakter), which is preserved until the present day” (Cameron 1998: 40). This description, similar to and perhaps derived from the Acts of Thaddeus, appears to be the most common way of understanding it during these centuries. Pilgrims traveling to the Holy Lands and Syrian-educated churchmen migrating elsewhere would undoubtedly spread what they heard about the Image. It is said that Pope Stephen (752 – 757) remarked “that he had often heard the story from those coming from the eastern parts of how Christ imprinted his face on a linen cloth and sent it to Abgar” (Chrysostomides 1997: xxxiii). Texts from outside greater Syria mentioning the Image are few before the later 8th century, but the great iconoclastic controversy (726 – 843) gave a major boost to its notoriety. Iconodules (“image lovers”) used it to argue Christ sanctioned pictures by making one himself.

In the image-friendly atmosphere of the Second Council of Nicaea (787) the Edessa Icon was noted several times, and Evagrius’ history was used to help explain its past. The assembled ecclesiastics were concerned “with establishing the proper degree of respect for religious images-veneration (proskynesis), but not worship (lateria)” (Cameron 1998: 45). Theodore Abu Qurrah, from the same monastery and with the same theological views as John of Damascus, wrote (very early in the 9th century) “As for the image of Christ ... it is honored by veneration especially in our city, Edessa, the blessed, at definite times, with its own feasts and pilgrimages” (Cameron 1998: 46). By the early 10th century Alexandrian Patriarch Eutychius assigns a lofty status to the Image writing “the most wonderful of His relics which Christ has bequeathed to us is a napkin in the Church of ar-Ruha [i.e., Edessa] .... With this Christ wiped His face and there was fixed on it a clear image, not made by painting or drawing or engraving and not changing” (Cameron 1983: 90). Eutychius uses the Arabic word mandil, usually understood to mean a handkerchief-sized cloth; other writers sometimes used “sweat-cloth” (soudarion), again suggesting modest size. These writers certainly imply that Christ’s imprint (ektypoma) was only of his face.

From the 8th to the mid-10th centuries, the Holy Image of Edessa gained renown as the most celebrated icon in Christianity. This period offers insights into its physical characteristics, although the secrecy surrounding it led to inevitable contradictions in descriptions. John of Damascus, an advocate for the veneration of images, who died in 749, described the Image as Jesus imprinting his likeness onto a cloth, a view mirroring the Acts of Thaddeus and widely accepted at the time. The story of the Image likely spread through pilgrims visiting the Holy Lands and Syrian-educated churchmen relocating to other regions. Pope Stephen, reigning from 752 to 757, reportedly heard tales from Eastern travelers about Christ transferring his facial image onto a linen cloth for King Abgar.

References to the Image outside the greater Syrian region were scarce until the late 8th century. However, the Iconoclastic Controversy (726 – 843) significantly amplified its fame. Proponents of icon veneration, called Iconodules, cited the Image as evidence of Christ's endorsement of images, as he himself created one. The Second Council of Nicaea in 787, fostering a pro-image environment, mentioned the Edessa Icon multiple times, using Evagrius' history to elucidate its background. The Council focused on defining the appropriate reverence for religious images: veneration (proskynesis) but not worship (latria).

Theodore Abu Qurrah, sharing theological views with John of Damascus and belonging to the same monastery, wrote in the early 9th century about the special veneration the Image received in Edessa, including dedicated feasts and pilgrimages. By the early 10th century, Alexandrian Patriarch Eutychius elevated the Image's significance, describing it as a miraculous napkin (mandil in Arabic, implying a small cloth) housed in the Church of ar-Ruha (Edessa). He emphasized the Image's enduring nature, not created by human artistry and unchanging over time. The term "sweat-cloth" (soudarion) used by some writers suggests its modest size, and it's clear from these accounts that the imprint (ektypoma) on the cloth was solely of Christ's face.

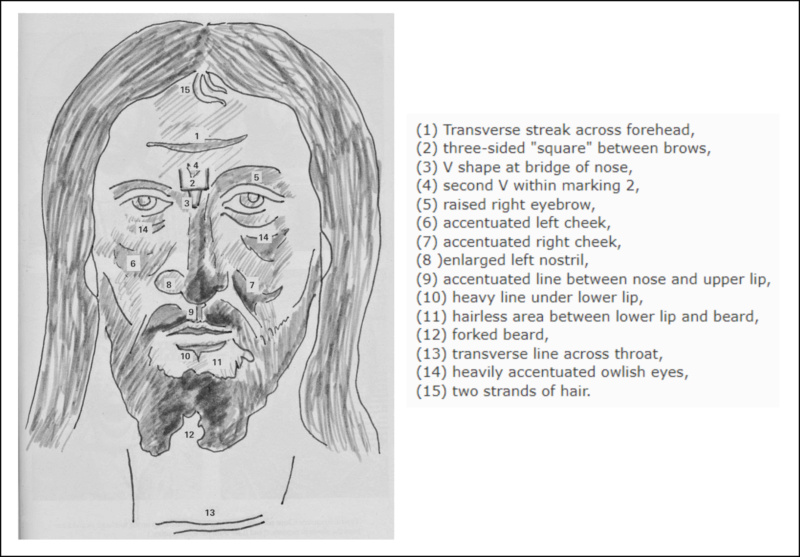

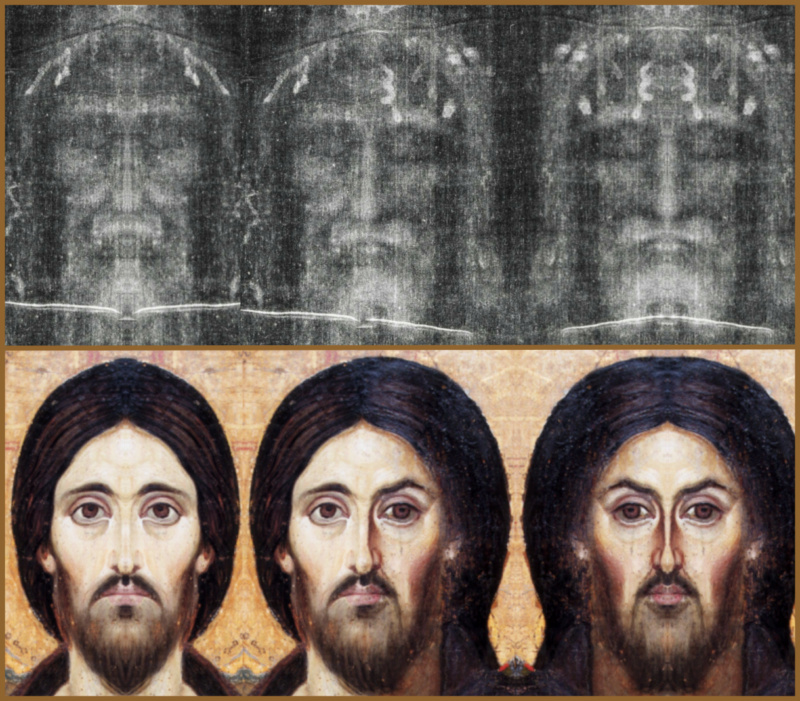

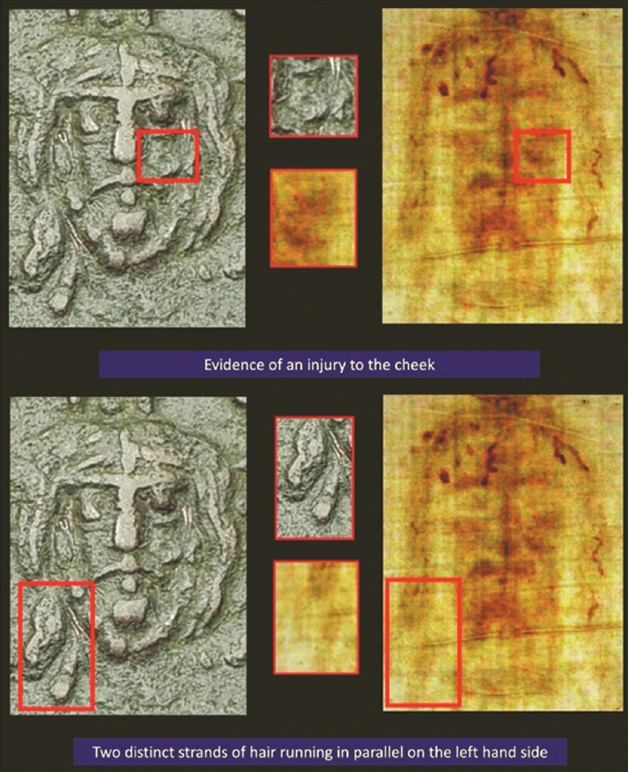

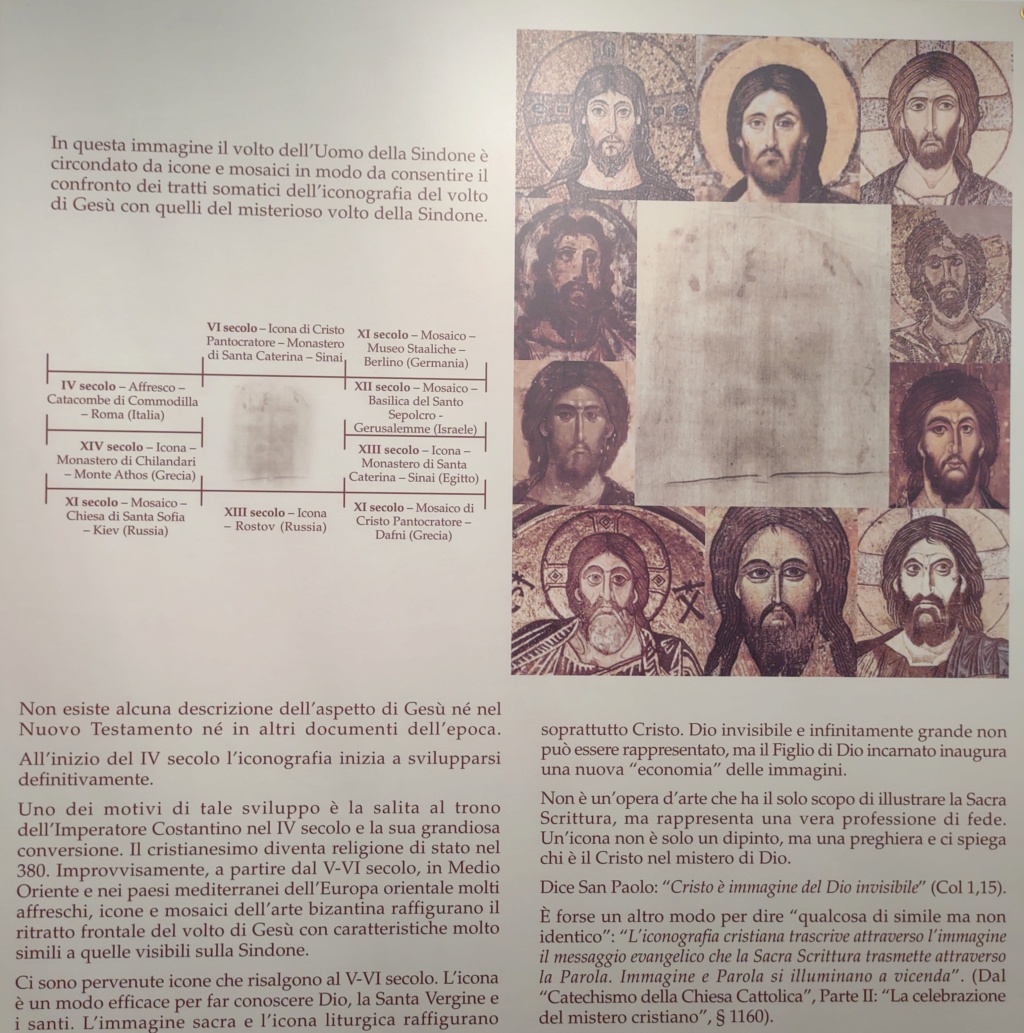

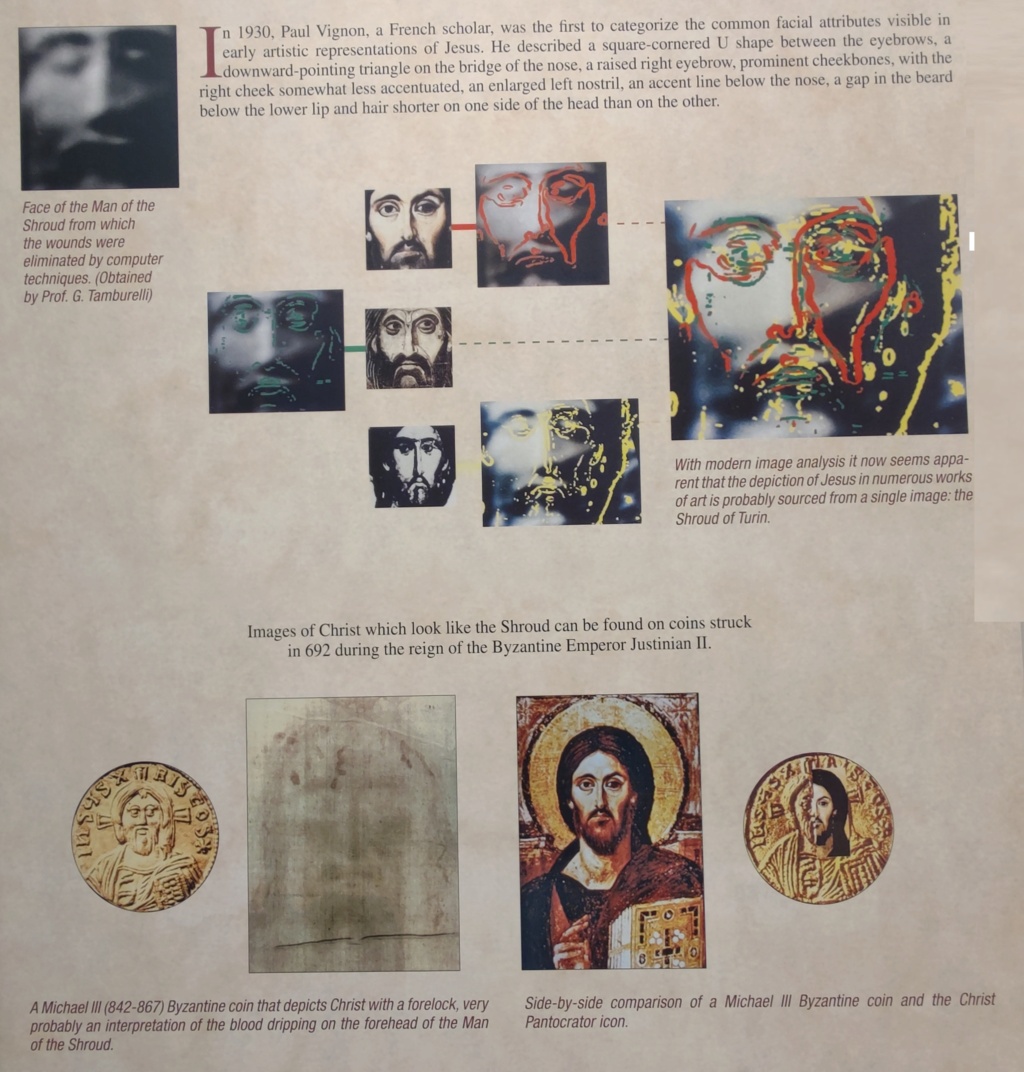

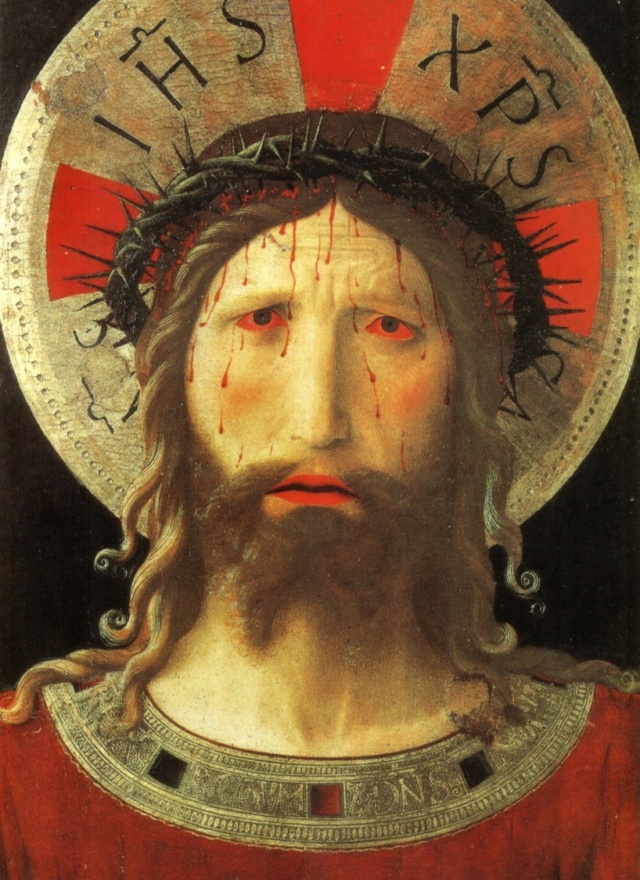

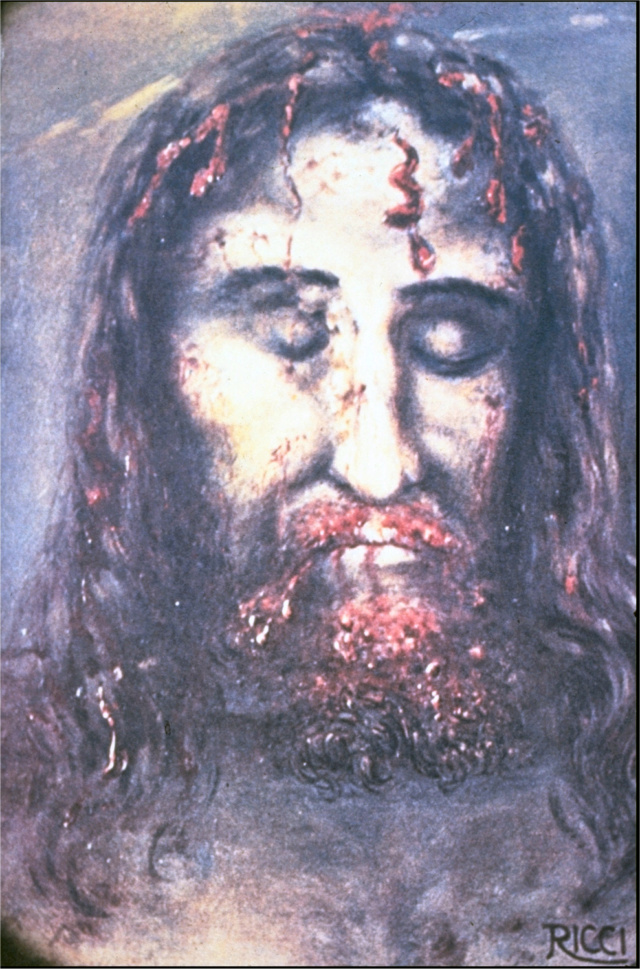

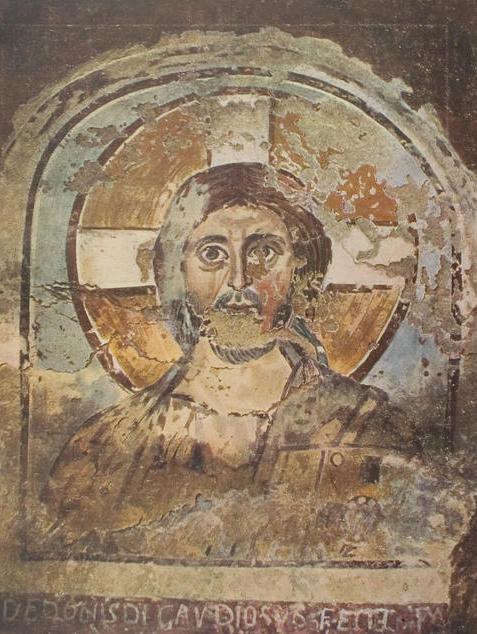

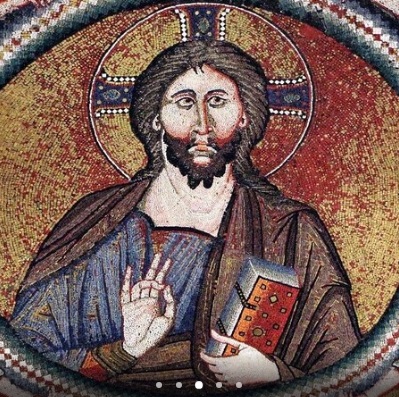

During these centuries, the emergence of new Christ images shows a notable influence from both the Shroud face and the Edessa Image. Wilson posited that artists replicated the facial area visible through the circular opening of the Image's slip cover, adapting it into various depictions of Jesus (Wilson 1979). This idea aligns with Vignon's earlier observation that numerous Pantocrator (Christ Enthroned) images bore a strong resemblance to the Shroud face, evident in the presence of distinctive "Vignon markings" (Wilson 1991).

One particular image in Rome’s Catacomb of St. Pontianus, dating back to the 7th century, drew attention due to its unorthodox features, such as an open topped square between Christ’s eyebrows, in addition to other characteristics aligned with the Shroud face, like a raised eyebrow and a long nose with one enlarged nostril (Wilson 1991).

Two 6th-century artworks in Rome – the mosaic in St. John Lateran and a painted panel in the Sancta Sanctorum Chapel – were both labeled as acheiropoietos, suggesting their inspiration from an original "not made by hands" image.

No known depictions of the Image in its frame exist from before the 10th century, yet certain works seem to capture the Christ face within a circular halo, similar to later representations of the Icon. Wilson identified two late 6th-century pilgrims' flasks (believed to be based on a now-lost mosaic from Jerusalem) and a 7th-century icon of Saints Sergius and Bacchus in Kiev, each featuring a rigid, front-facing face within a circular field (Wilson 1979).

The Veronica portrait, a revered Vatican relic potentially dating to the 8th century (though Wilson suggests the early 11th), is often considered by scholars to be a derivative of the Edessa Image (Meagher 2003). The more widely known Veronica image, displaying a very realistic face, likely diverges from the original icon’s appearance, which is thought to have had a more blurry, impressionistic texture akin to the Shroud.

During this era, the prevailing notion that the Edessa Icon was merely a small cloth depicting Jesus' face is contested by accounts implying a connection to the Turin Shroud and suggesting a larger cloth with more comprehensive imagery.

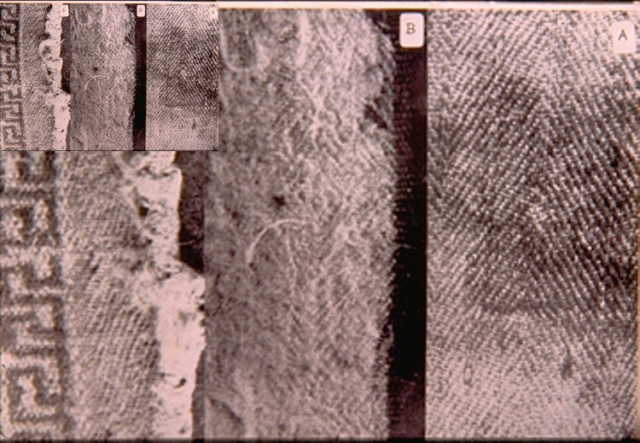

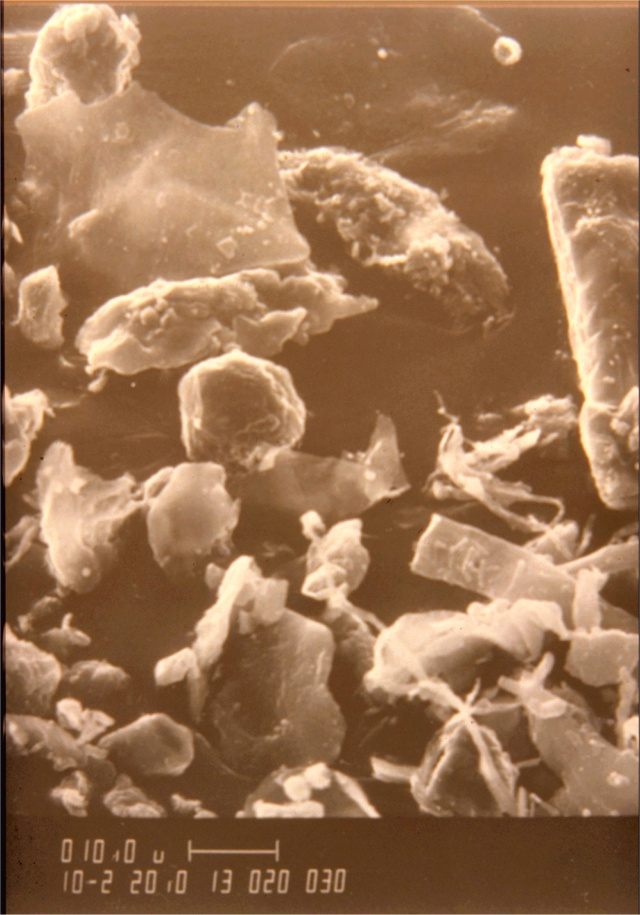

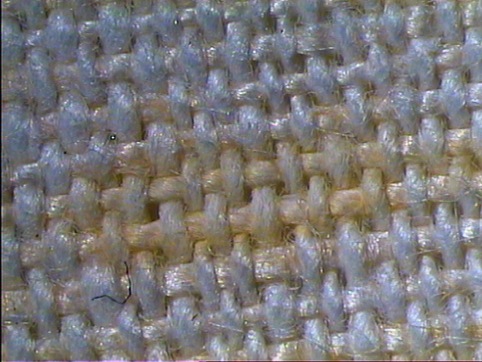

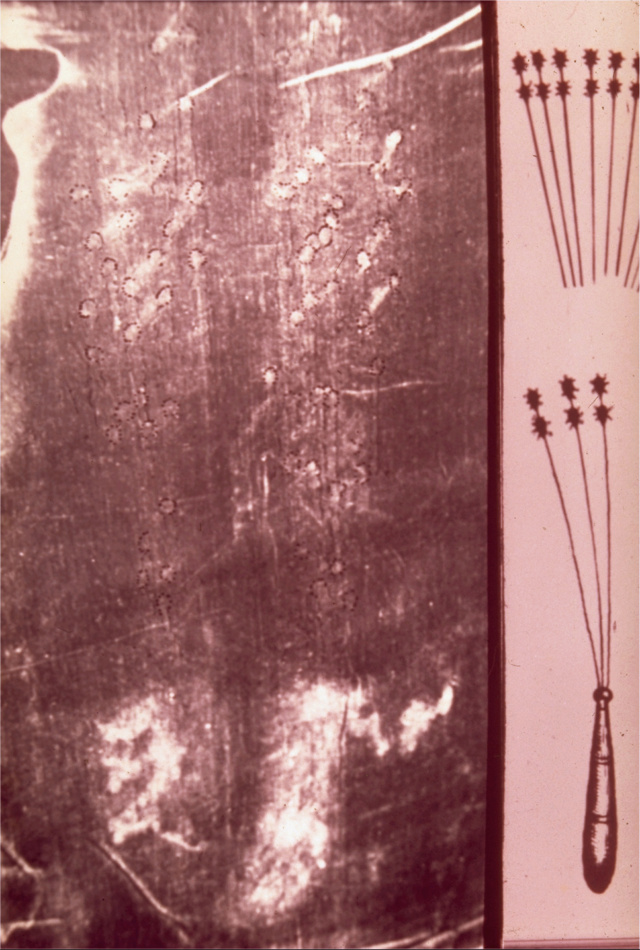

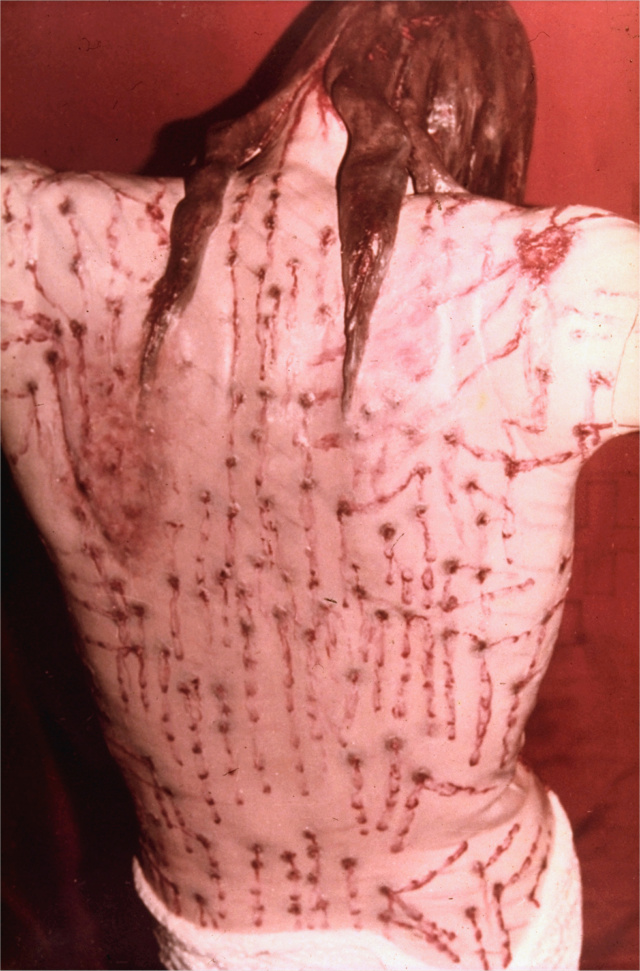

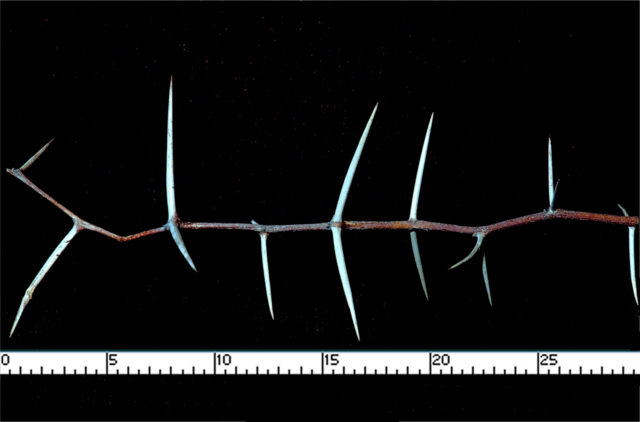

Wilson's observation of the term "tetradiplon" in the Acts of Thaddeus is particularly noteworthy. This term, indicating a cloth "doubled in four," in a narrative not primarily about the Image but rather Edessa's evangelization, implies firsthand knowledge of this unique characteristic. This detail becomes meaningful if the cloth was large, bearing a face in the same position as on the Turin Shroud. Andrew of Crete in the early 8th century described the Image as the imprint of Christ's "bodily appearance," diverging from descriptions limited to just a face. This implies a cloth large enough to cover a body, raising questions about its actual size compared to a mandil. John Damascene's reference to Christ imprinting his facial image onto Hanan's himation, an outer garment approximately the size of the Shroud, further supports this larger size hypothesis. The Image's color and texture are alluded to in the account of Athanasius bar Gumoye’s painter who reportedly "dulled" its colors. A 9th-century Constantinople writer, referring to an earlier description by Patriarch Germanos, described the Image’s face as "sweat-soaked." This term could be an attempt to describe the Shroud's unique, diffuse, monochromatic, and moist-like appearance, familiar to those acquainted with the icon colors of that era. Massoudi, a 10th-century Muslim historian, seemingly unaware of the Abgar story, understood the cloth to be used for drying Christ after baptism. Scavone interprets this as indicating a larger cloth used on a damp body, a more straightforward, natural explanation. Massoudi's awareness that the Icon "circulated" before reaching the Edessa cathedral suggests there may have been more extensive knowledge about its early history that has not been preserved. Yet, these references are merely suggestive. A more definitive link between the Icon and the Shroud would require a clear assertion of a full-body image, specifically depicting Christ’s Passion. Such evidence, indeed, does exist.

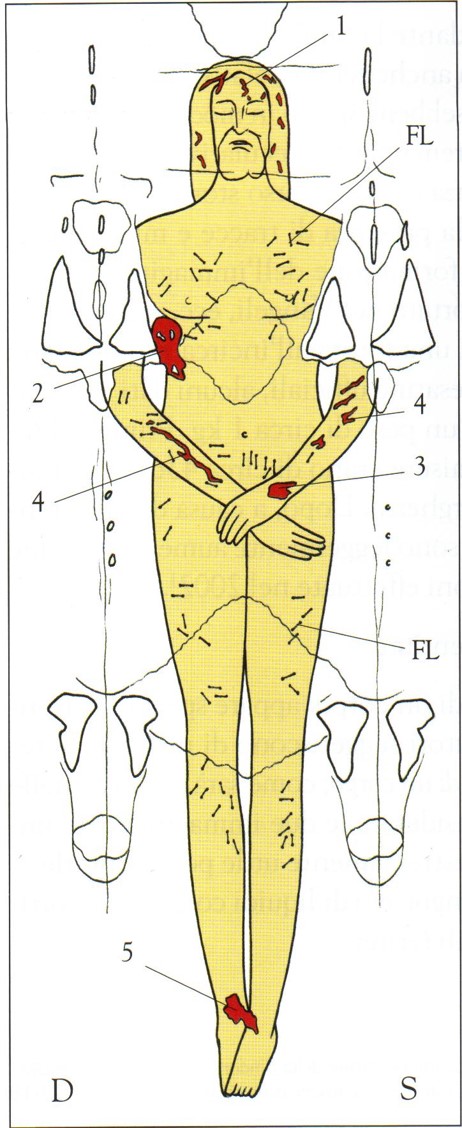

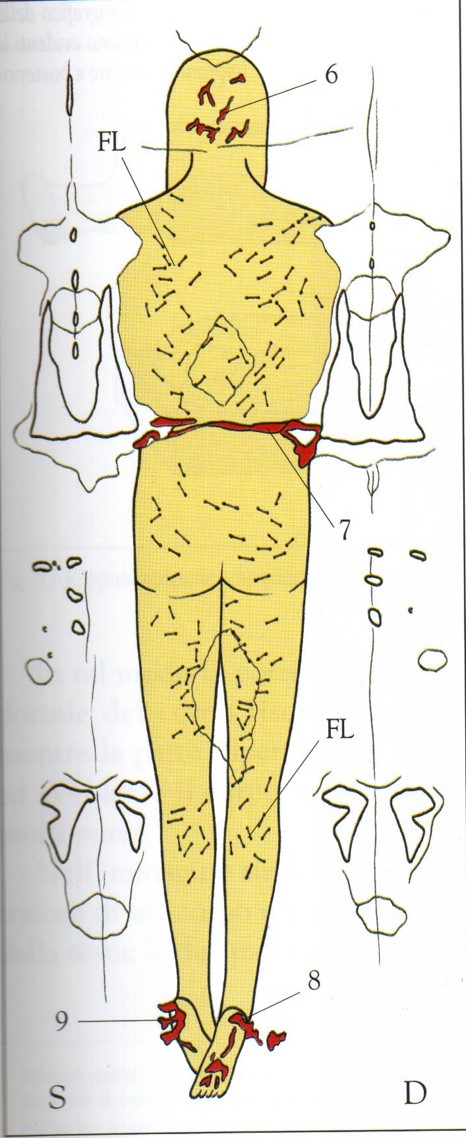

In the 1960s and 1970s, research into the Image of Edessa initially overlooked significant evidence that the Syrian custodians of the Icon might have been aware of the concealed full-body image within its folds. It was believed that the cloth was folded and framed during the time of Abgar and remained unchanged until the 11th century. However, a 12th-century Latin text by the monk Odericus Vitalis, one of the earliest to reveal the full-body image, suggested a different story. Ernest von Dobschutz, a 19th-century historian, had noted that this and similar Latin documents from around the same period, which reported a full-body image, likely had their origins in a Syriac text from around 800. This hypothesis was further supported in 1993 with the discovery of an earlier Latin text from the 10th century, known as Vossianus Latinus Q69. These manuscripts, containing the "Oldest Latin Abgar Legend," suggest that the Edessa Image depicted the entire body of Jesus and likely originated from a Syriac source predating 769. In these texts, Jesus responds to Abgar's request for a visitation by promising to send a linen cloth. This cloth, as described, would reveal not just the features of Jesus' face but a divinely replicated image of his entire body. The narrative then continues to unfold, providing further insights into the history and nature of the Edessa Image.

The 10th-century tract Vossianus Latinus Q69, translating a probable 8th-century Syriac text, describes the Edessa cloth as depicting a whole-body image of Christ. This revelation began to hint at the true nature of the icon, previously thought to be just a facial imprint. The tract vividly describes how Jesus laid his entire body on a white linen cloth, resulting in the divine transfer of not only the lordly features of his face but also the majestic form of his entire body. This linen, remarkably preserved over time, was said to be housed in a great cathedral in Edessa, Syrian Mesopotamia. The original source of this legend, likely an earlier Syriac text, brings into focus the possibility that the Edessa Image aligns with the image on the Shroud. Furthermore, some of these texts, including Vossianus Latinus Q69, subtly hint at a connection between the cloth and Christ’s Passion. One particular passage describes how the cloth's appearance changed throughout Easter day, mirroring Christ’s life stages from infancy in the early hours to the fullness of age at the ninth hour, coinciding with the time of Christ’s Passion and Crucifixion. This description, suggesting a dynamic and evolving image, has led some scholars to speculate that the Edessa cloth could have borne a wounded, bloodied whole-body image similar to that on the Shroud. The text implies that the image might have been revealed progressively during an Easter ritual. However, a clearer understanding of these mysteries would require additional evidence, ideally from eyewitness accounts. By the later part of the 10th century, more such witnesses appear, providing further clarification on the nature of the Edessa Image.

Vossianus Latinus Q69, describing the Edessa Icon, also intriguingly mentions a mysterious Easter ceremony during which the image seemed to transform throughout the day to depict various stages of Christ's life, culminating in his Passion. This reference to a dynamic, changing image during a ritual adds a layer of complexity to our understanding of the Icon. In the early 7th century, Byzantium, under Emperor Herakleios, witnessed a series of military victories that briefly restored its glory before the rise of militant Islam, which led to Edessa falling under Muslim control in 639. The subsequent centuries saw the empire endure two Arab sieges of Constantinople and grapple with internal strife, notably the iconoclasm controversy. This period was marked by a division between iconodules, who venerated religious images, and iconoclasts, who opposed them, often with the support of the emperor's authority. This conflict resulted in injuries, banishments, and the destruction of much religious art. Eventually, iconodules triumphed in 843, restoring the use of religious images in Byzantine life. The imperial family played a significant role in religious affairs and sought to acquire major icons and relics for prestige.

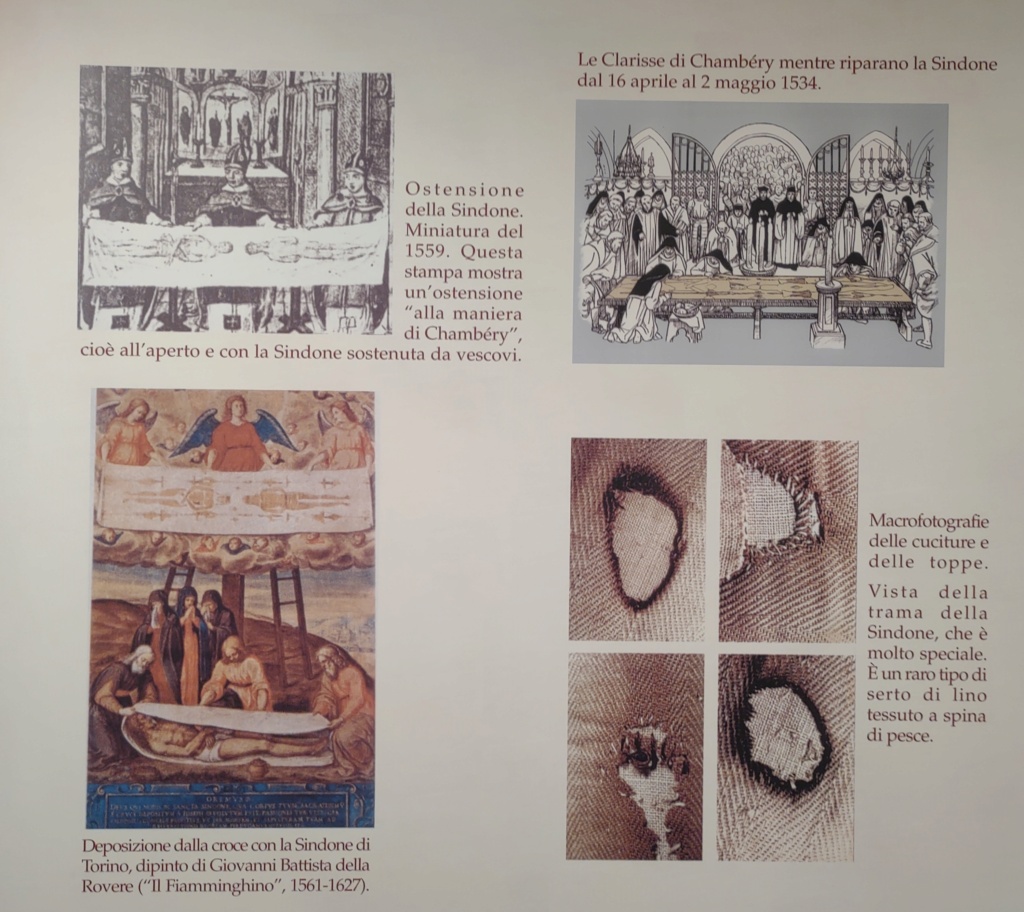

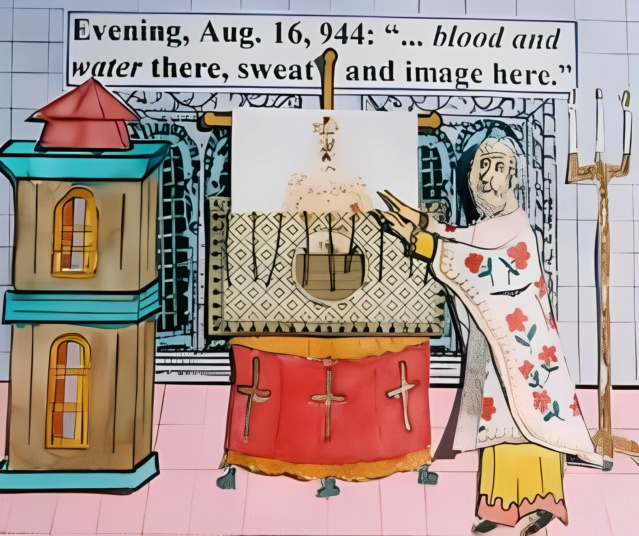

In 943, to mark the centenary of the "Triumph of Orthodoxy," Emperor Romanus Lacapenus sent an army to seize the Edessa Image from the Muslims. The declining military might of the Muslims meant little resistance to the Byzantine forces. Although Islam shared an iconoclastic stance, Muslim rulers appreciated the fame and economic benefits brought by pilgrims to cities harboring revered relics. In 944, a deal was struck with the city’s emir, involving payment, prisoner release, and assurance of no further attacks in exchange for the Image. However, the Christian populace resisted, initially offering copies. It was only after a bishop, familiar with the original, identified the true Icon that it was handed over, despite protests from the Edessan people. At this time, the Eastern Christian Empire was nearing its zenith. Constantinople, formerly Byzantium, stood as Europe's most splendid city. It was a hub of art, culture, and commerce, preserving the legacy of the Roman Empire. Its wealth from trade, along with its magnificent palaces, churches, and shrines, made it the envy of the world. This historical backdrop provides context to the reverence and intense devotion the Edessa Icon inspired, as well as the fervor surrounding its eventual transfer to Constantinople.

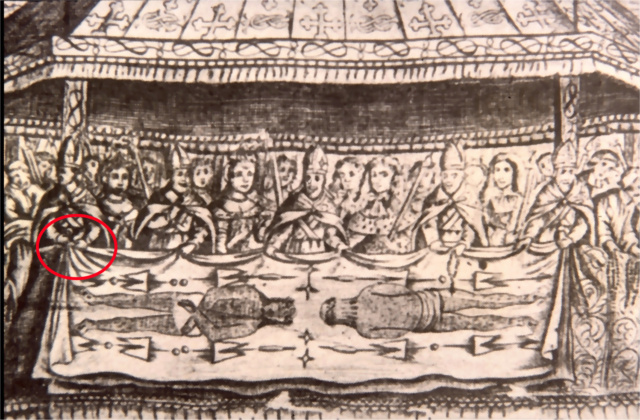

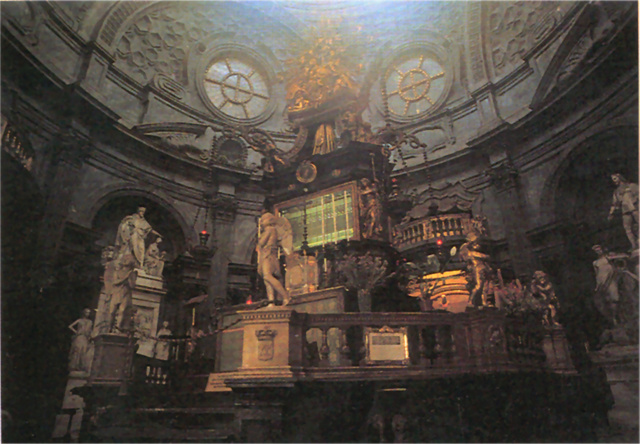

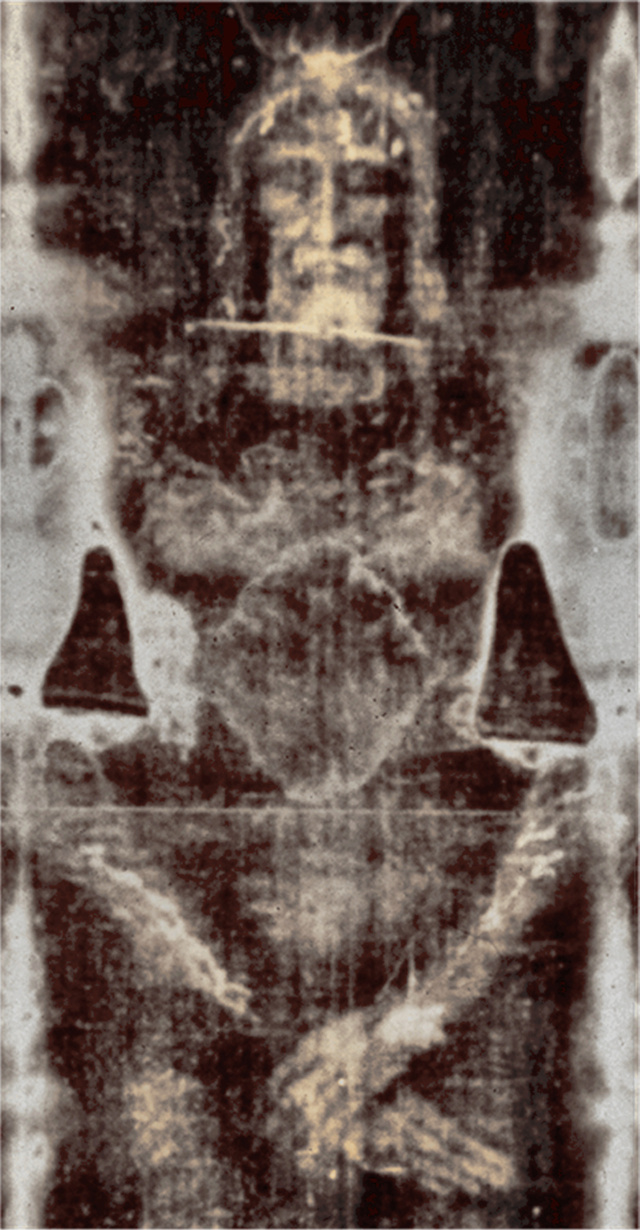

In the 10th century, Constantinople, Europe's most eminent city and the heart of the Orthodox Christian world, received the Holy Image of Edessa, the most venerated Christ picture of its time, into its treasury of relics. Subsequently, almost all Orthodox churches began to feature representations of this Image within their church art, as noted in the December 1983 issue of National Geographic. The Image was first brought to the Church of St. Mary Blachernae in the city's northwest corner on the evening of August 15, 944, coinciding with the Orthodox celebration of the Assumption of the Virgin. A select group of clergy and nobility gathered to preview this renowned picture. An event, possibly that same night or shortly after, was depicted in a small painted miniature from the 12th or 13th century, part of over 600 illustrations for a history by the Greek John Skylitzes. This miniature shows the aging emperor embracing a cloth with a typical Jesus face, stretched in a picture frame. Adjacent to the Image is a long cloth, possibly indicating the actual size of the cloth or a separate handling cloth used for protection (Crispino 1992).

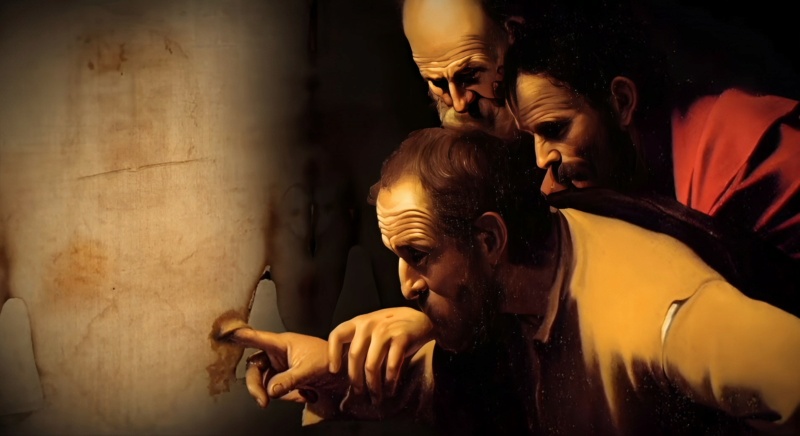

However, the later artist made a significant error in depicting the Jesus face. According to a 10th-century account by Symenon Magister, the emperor’s sons, present at the viewing, could barely make out a faint face, while their brother-in-law and future emperor, Constantine VII, an artist himself, could discern various facial features. This struggle to interpret the image suggests that the nobility, accustomed to the finest art in Christendom, were actually viewing a blurry image akin to that on the Shroud. The following day, the Image was officially welcomed into the city, described as the new palladium, amidst high psalmody, hymns, and a bright display of torchlight in a procession involving the entire populace. A contemporary history records the event, emphasizing the indescribable joy, tears, prayers, and thanksgiving from the entire city as the divine image was paraded through the streets. This historical account vividly captures the profound impact and reverence the Holy Image of Edessa held upon its arrival in Constantinople.

Shortly after the arrival of the Edessa Image in Constantinople in August 944, Emperor Romanus, his sons, and their entourage had a private viewing of this revered relic. Although a picture made about two hundred years later depicts a clearly imprinted face of Jesus on the cloth, contemporary accounts noted difficulties in discerning the face, as recorded in "The Catholic Counter-Reformation in the XXth Century, No. 237" (March 1991). During the grand celebration on August 16th, the Holy Image was placed on the Mercy Seat in the Hagia Sophia, the most prestigious church in Constantinople. It was later stored in the Pharos Chapel, a secretive area within the emperor's Great Palace, reserved for the most valued treasures. Around this time, another exclusive viewing occurred, likely for a select few. An 11th-century copy of a sermon preached during this event was discovered in 1986 by Shroud researcher Gino Zaninotto. The sermon was delivered by Gregory, an important cleric and archdeacon of Hagia Sophia, who possibly oversaw the Icon's reception in Constantinople. Gregory revealed in his sermon that a delegation had traveled to Edessa, hoping to uncover manuscripts detailing King Abgar's actions. They found numerous Syriac manuscripts, which they translated into Greek.

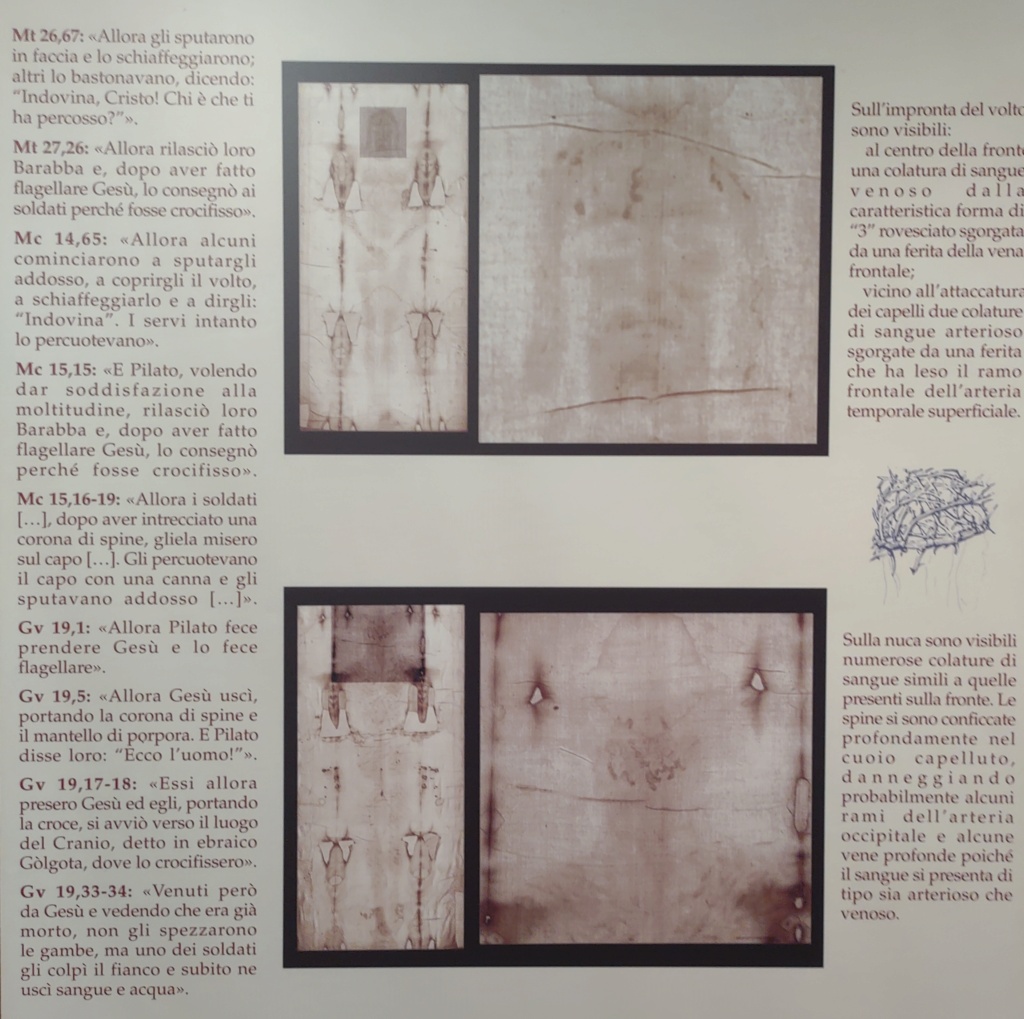

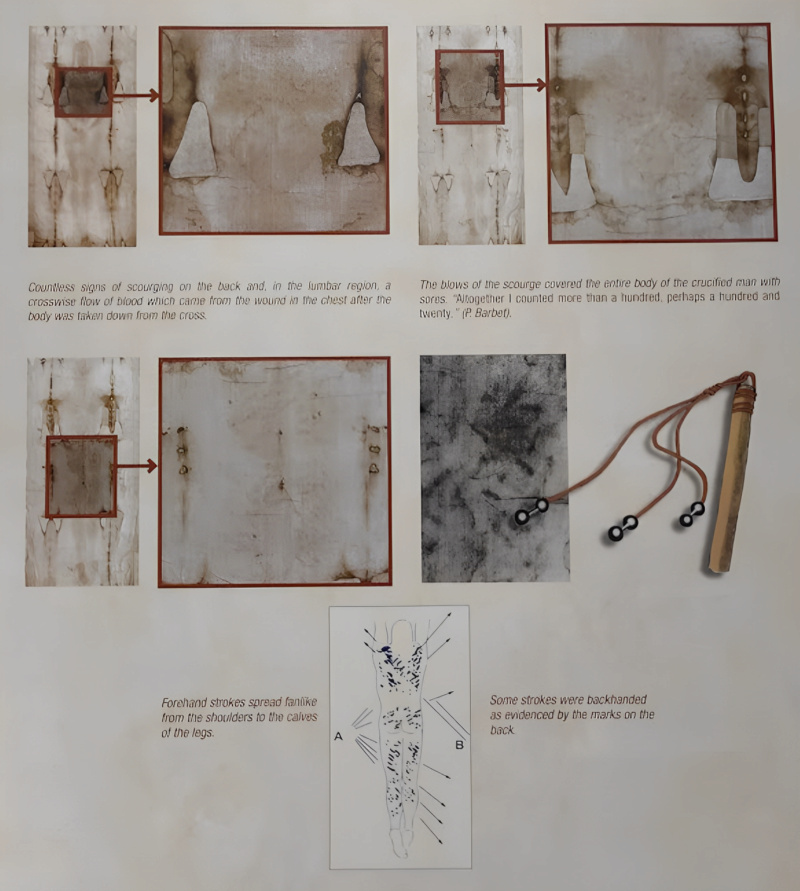

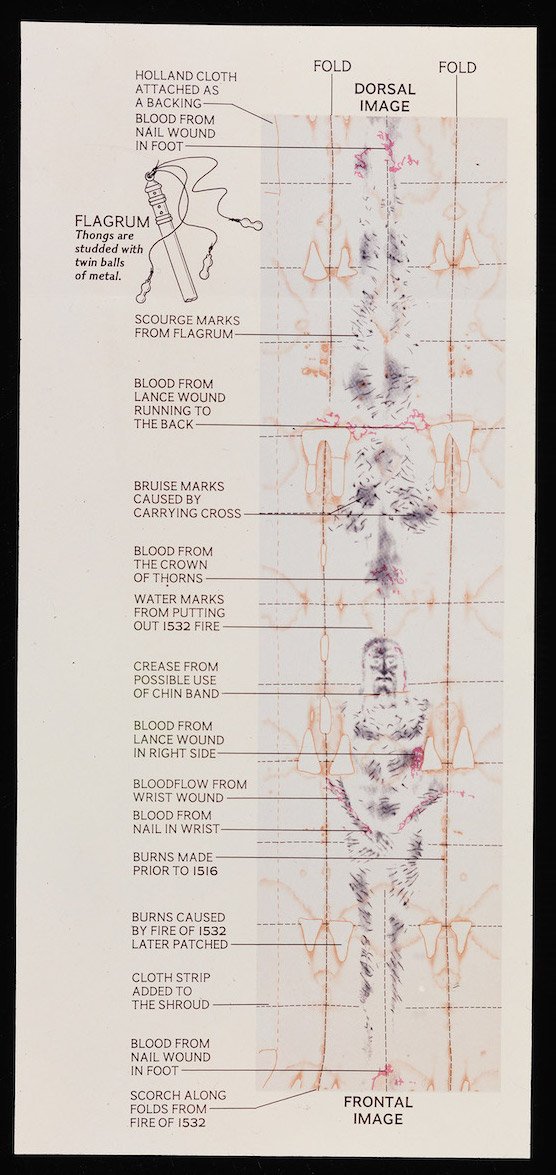

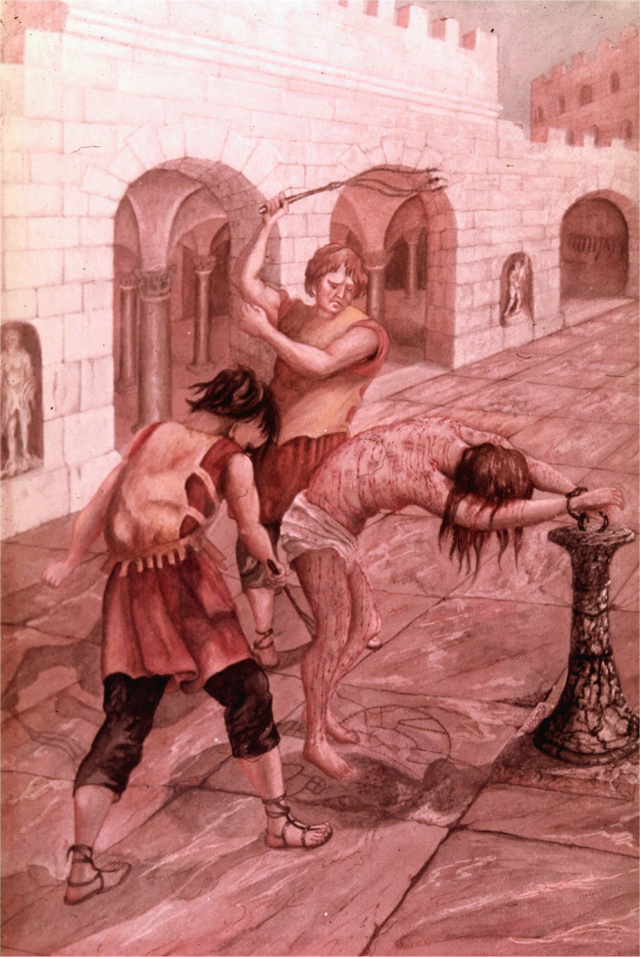

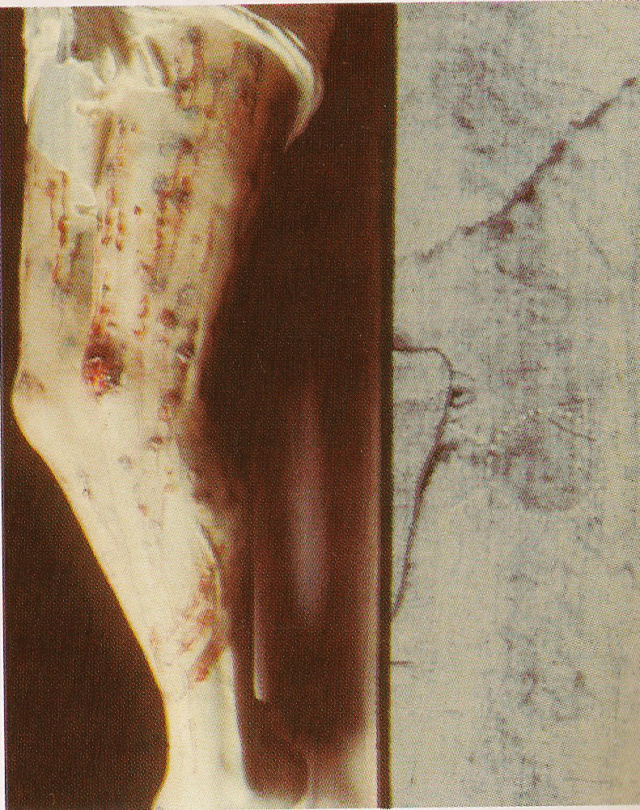

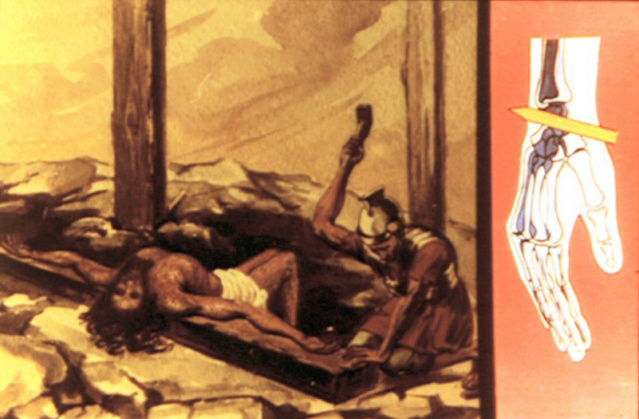

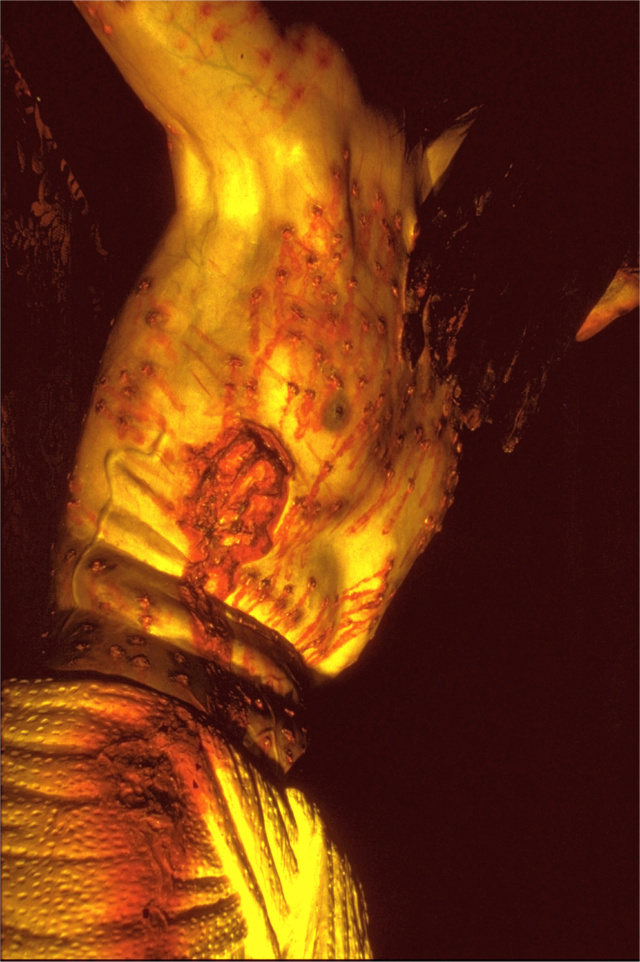

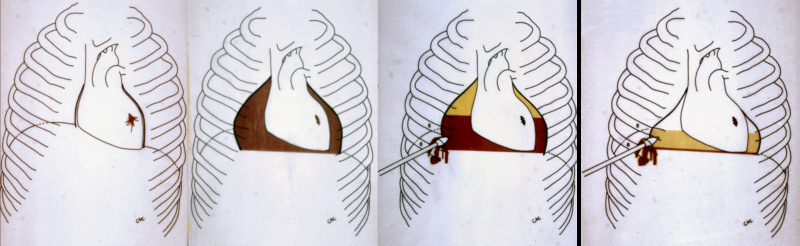

Gregory clarified in his sermon that the Image was not created during Christ's ministry, but rather when Jesus, enduring his passion, used the linen cloth to wipe his sweat, which was falling like drops of blood during his agony. As Gregory spoke, the Image was likely more visible to the audience than on any other public occasion. He described the reflection of Jesus' image as imprinted solely by his sweat, falling like drops of blood, and referred to it as the work of God. He mentioned the combination of sweat and image, and also noted the presence of blood on the Image, drawing parallels to the Gospel accounts of blood and water flowing from Jesus' side when lanced on the cross.

Gregory's words initially led many to believe he was indicating a visible wound on the Image, reflecting the wound on Christ's side. However, recent scholarship suggests that the Greek text only shows Gregory reflecting on the Gospel narrative, not observing such a wound on the Image. This interpretation still leaves open the possibility that the Image could have borne a side wound, seen or not. Gregory's account serves as a firsthand testimony, linking the Image more closely to the events of Jesus' Passion, and advancing the association with the Shroud.

After the Edessa Image's arrival in Constantinople in August 944, a privileged display was organized, where the knowledgeable cleric, Gregory, observed features reminiscent of “sweat ... falling like drops of blood” from Christ’s head, evoking thoughts of the wound in Jesus’ side. A few years later, Emperor Constantine VII, who had a significant collection of relics, mentioned possessing “blood from his side,” raising questions about its acquisition. In the following year, the Icon was honored with its own feast day on August 16th in the Orthodox calendar. To commemorate this event, a detailed history, possibly authored by Emperor Constantine VII, was written. Known as the "Story of the Image of Edessa," it's the first comprehensive account of the Image's 900-year history, offering a close-up eyewitness perspective since its arrival in Constantinople. Also called the “Festival Sermon,” it claims to be grounded in “painstaking inquiry into the true facts” from historians and Syrian traditions. This work likely drew from the same Syrian manuscripts as Gregory's earlier sermon. The Story recounts King Abgar's ailments and his request for Jesus to come to Edessa. According to the narrative, Jesus declined but promised to send a disciple after ascending to his Father. He then washed his face, leaving an impression of his likeness on the towel. A variation of this story in the manuscript suggests the Image was created during Jesus' agony in Gethsemane, where sweat, likened to drops of blood, transferred his divine face onto the cloth. Thaddaeus, the disciple sent by Christ, brought both the Gospel and the Image to Edessa. Abgar noted the Image's supernatural qualities, observing that its likeness was due to sweat, not pigments. The Story also details how the Image was revered in Edessa, later concealed atop a city gate during a period of Christian persecution, and then rediscovered during a Persian siege, as described by historian Evagrius. The narrative includes numerous miracles and may have been a lecture to a select audience, echoing Gregory's sermon.

However, historians view much of the early history of the cloth as described in the Story with skepticism, considering it semi-legendary. The narrative does not equate the Image with a burial shroud but speculates on the nature of the face, comparing it to blood marks on the Shroud and suggesting the bloody sweat from Gethsemane as a possible cause for its appearance. The Story aligns with a hypothesis that the Shroud, like the Image, was hidden and later rediscovered.

A significant flood in Edessa in 525 and subsequent rebuilding might have provided an opportunity for this rediscovery, aligning with the emergence of Shroud-like Jesus faces in Ravenna mosaics in the early 540s. Additionally, reports of Assyrian monks associated with the Edessa Image traveling as "icon evangelists" in the early 6th century lend credence to this theory. The Story also recounts a later event in Edessa's history when Turkish forces in 1146 destroyed the Christian civilization there. During their year-long search, they discovered many hidden treasures, suggesting a historical precedent for valuable items being lost and later found.

The early documents hinting at a full-body image on the Edessa Icon, alongside the more explicit claims in the "Oldest Latin Abgar Versions" and the observations of Jesus' Passion made by Gregory and others who closely examined the Image, gradually led its new custodians in Constantinople to consider that what they had acquired in 944 might actually be Christ's burial shroud. By 958, Emperor Constantine VII was aware of several Passion relics in his treasury, as detailed in a letter aimed to bolster his troops near Tarsus. He mentioned possessing relics like the precious wood, the unstained lance, and notably, the life-giving blood from Christ's side, and the sindon, among others. This reference to the sindon is considered the earliest mention of any burial cloth in Constantinople. The precise identity of this sindon has been a subject of debate, especially given the lack of a celebratory welcome for such an important artifact. However, its existence gains clarity in light of the rediscovered Gregory Sermon. If the Edessa Image was indeed the Turin Shroud, it's plausible that the emperor and chief clerics would recognize and utilize it as such. From this point forward, a shroud is documented in Constantinople at least once each century, albeit kept under great secrecy and never directly shown to the public until just before its 1204 departure.

The term "Mandylion," commonly used to refer to the Edessa Image and derived from the Arabic word "mandil" (handkerchief), was not initially used as a name for the Icon upon its arrival in Constantinople in 944. It became more commonly used later in the 10th century, although not by its caretakers. The late 10th-century writer Leon Diaconos still describes it as a large cloth, calling it a peplos (robe). Monasteries on Mt. Athos around this time or slightly later recorded the old Abgar stories, with the king now asking for a full-body painting of Christ. Once in Constantinople, a painted picture of the Image became standard in most Eastern churches, with the original considered the source of Christ's true appearance. Early depictions typically show Jesus' face in a circular opening of an ornate, trellis-pattern slipcover. The Icon's horizontal, landscape shape in many early pictures aligns with the Shroud being "doubled in four." Why the Edessa Image's true nature as a burial shroud was not openly declared raises questions. The depiction of a brutally beaten, bloodied, and naked Christ on the Shroud was contrary to early Christian sensibilities, which found such imagery abhorrent. Early Christian art was hesitant to depict Christ realistically on the cross, with more vivid portrayals emerging only in the 13th century in the West. The stark reality of the crucifixion's effects visible on the Shroud likely led to its cautious handling and prudent silence about its true nature. Understanding of the Christian Orient at the time suggests that the guardians of the Shroud were unlikely to publicly display it, particularly in conservative regions like Syria and even in the relatively more liberal Constantinople. Furthermore, Constantinople's authorities faced the challenge of how to present such a sensitive and significant relic.

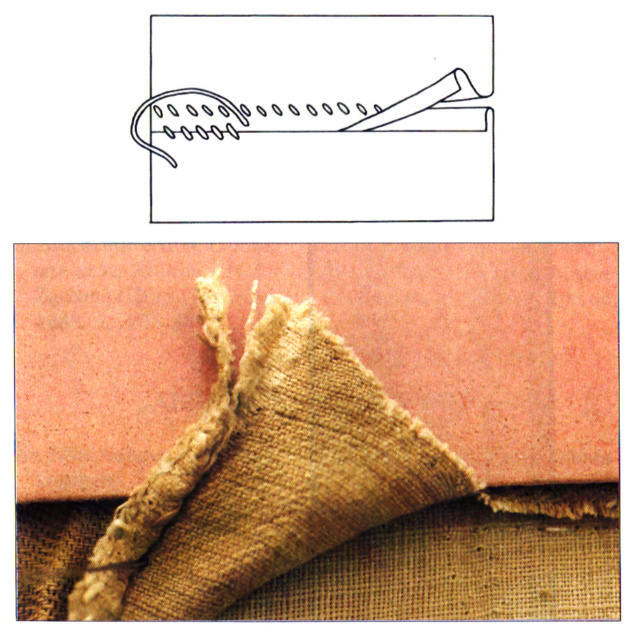

The dilemma faced by new Emperor Constantine VII and the Orthodox tradition was how to reconcile the deeply ingrained story of the Edessa Image, a face cloth believed to bear the imprint of Jesus, with emerging evidence suggesting it was more than just a facial portrait. This Icon had become a celebrated part of extra-biblical stories and a pillar in Orthodox tradition. The idea that it might have been something else all along would have been a challenging revelation for both the emperor and the patriarch. The Edessans had seemingly promoted the story of the Abgar facial portrait to obscure the full truth of the Image. However, various hints and versions of the story, including mentions of tetradiplon, himation, and the "Oldest Latin Abgar Legend" which alluded to a full-body image, indicated that the true nature of the relic was gradually being revealed. Faced with this situation, Emperor Constantine VII seems to have chosen a more nuanced approach. A possible solution was the introduction of a copy of the Mandylion into the emperor’s collection of relics. This strategy allowed for the continuation of the old Abgar tradition while simultaneously acknowledging the presence of burial linens. By the late 11th century, records indicate the existence of both a Mandylion and burial shrouds, suggesting that the original Edessa Image may have functioned in both capacities for a time. The Byzantines could thus preserve the old traditions and avoid disclosing the true origins of the new shroud. An additional point of interest regarding the Edessa Image, now referred to as the Mandylion and potentially also the Shroud of Constantinople, is the possibility of it having been folded or “doubled in four” for centuries. This hypothesis is supported by the presence of fold marks at one-eighth length intervals on the Turin Shroud, as observed by Dr. John Jackson, a leading scientist on the 1978 Shroud of Turin Research team. These folding patterns, not known to have been used during the Shroud's documented history since the 14th century, along with other crease lines, suggest a complex history yet to be fully uncovered.

Last edited by Otangelo on Sat 16 Dec 2023 - 15:06; edited 16 times in total