https://sabanasanta.org/ostensiones/

The Shroud of Turin: A History of Devotion, Art, and Dynasty

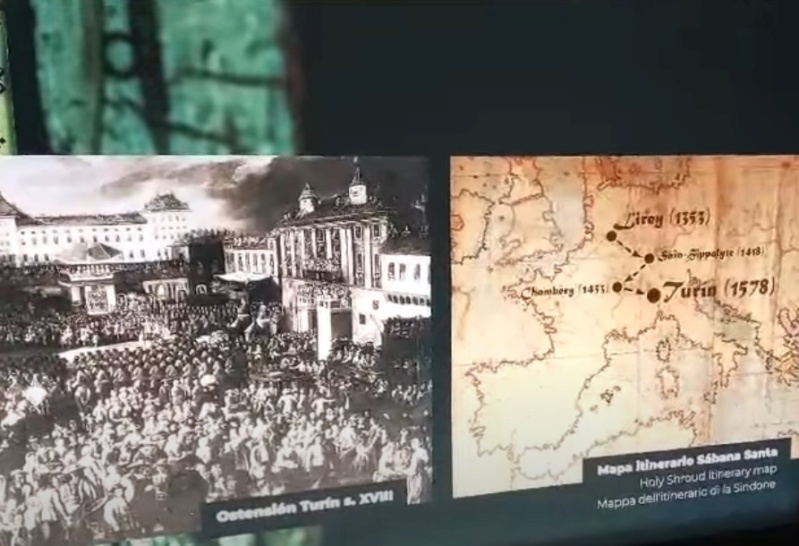

The Shroud of Turin, an enigmatic and revered religious artifact, has a complex and fascinating history. The first documented evidence of its existence is a medieval lead pilgrimage medallion found in 1855 at the bottom of the Seine in Paris, near the Pont au Change, and currently housed in the Musée de Cluny. This medallion, along with numerous other artifacts discovered in the same location, attests to the tradition of pilgrims throwing such items into the river as part of an apotropaic rite upon entering Paris. These findings underscore the devotional significance of the Shroud in France since the 14th century. The Shroud is primarily renowned for being an extraordinary image. It is a direct and objective representation that requires no mediation for recognition. Its existence as an image is undeniable, and it has been replicated in various forms since its appearance. The Shroud began to be reproduced in different styles, materials, and techniques, aimed at making this image widely accessible, especially to those unable to attend its public displays.

Initially, depictions of the Shroud were devotional in nature, a trend that persisted for a long time. The production of various images of the Holy Shroud began in the 16th century, peaked in the Baroque period, and then declined until it was virtually replaced by photographs in the late 19th century. These images were primarily designed for religious practices. Apart from devotional reproductions, a substantial number of images were created to commemorate historical events, particularly highlighting the relationship between the Savoy dynasty and this dynastic relic. The Savoy acquired the Shroud from Marguerite de Charny, a granddaughter (but not a direct descendant) of Geoffroy de Charny. The circumstances of the acquisition were complex, given Marguerite's precarious claim and legal challenges from the canons of Lirey.

Initially, the Shroud played a private, predominantly female devotional role in the Savoy household, often traveling with the court. Its public significance grew over time, notably after the 1503 public display in Bourg-en-Bresse and the 1506 granting of the liturgy of the Shroud. It gradually assumed its role as a dynastic relic, symbolizing the divine favor and legitimacy of the Savoy dynasty. The presence of such a significant religious object was a common practice in European courts, signifying divine favor and entrusting the dynasty with its care. For the Savoy family, guardianship of the Shroud, which bears the image of Christ's face and wounds, was particularly prestigious. However, this also obligated the sovereign to embody the virtues of a true Catholic prince, recalling figures like St. Charles Borromeo or Blessed Sebastiano Valfrè.

From a devotional standpoint, the Shroud of Turin has been represented in a multitude of ways. Frescoes, adorning both public and private spaces, serve as significant testimonies to the Shroud, although many have deteriorated or become illegible over time. These frescoes, often placed in highly visible areas like house doors or town entrances, served an apotropaic purpose. Representations of the Shroud alone are rare; it is usually depicted alongside the Virgin Mary, who helps present it, or with saints who had some connection to it. These saints might be linked to devotions to the Incarnation and Passion of Christ, like St. Francis, or to other local or popular devotions, or even to figures associated with the dynastic pantheon. Occasionally, these depictions include historical elements, such as public displays of the Shroud. These frescoes are found across various regions, from Savoyard France to Piedmont and even Lombardy, with less presence in areas more recently acquired by the Savoy State. Frescoes are also a part of the interior decoration in places of worship. However, the knowledge and depiction of the Shroud extended far beyond these regions, as evidenced by artworks like the large canvas attributed to Francesco Bassano the Younger in Treviso Cathedral or the late 16th-century depiction in the Vatican's Gallery of Maps. The latter illustrates the growing religious significance of the Shroud within the Savoy territories.

Additionally, there are paintings of various sizes, sometimes created by notable artists, and a variety of personal devotional items like Books of Hours, small paintings, prints, and embroideries. With the advent of printing, the reproduction of Shroud images became widespread, enabling mass dissemination. The increase in Shroud representations in the mid-16th century coincided with various needs. With Emanuele Filiberto moving the capital to Turin and asserting his dynasty after challenging years, there was a keen interest in promoting the dynastic relic. This policy continued with his successors, coupled with a genuine personal devotion shared by the sovereign, court, and public. For instance, King Charles Felix's deep religious devotion led to a public display of the Shroud during his unexpected accession. Public displays of the Shroud, especially during dynastic events, became increasingly elaborate, reflecting the relic's attributed significance. After relocating the capital from Chambéry to Turin, symbolizing a new political will, Emanuele Filiberto commissioned three works from court historian Emanuele Filiberto Pingon. These works aimed to strengthen the dynasty's image and the new political direction. They included a reconstruction of the Savoy genealogy, a text on Turin highlighting its role and antiquity, and a book on the Holy Shroud – the first dedicated entirely to the relic. Pingon's efforts, despite some challenges and lack of documentation, laid the foundation for subsequent reconstructions of the Shroud's history and confirmation of its status as a relic. Beyond the "Savoyan need," the ecclesiastical perspective played a role. Post-Council of Trent, the Church saw representations of relics and images as powerful tools for catechesis and strengthening spirituality and doctrine.

The Shroud, with its unique characteristics, emerged as a key instrument in the Catholic Reformation. Esteemed figures like St. Charles Borromeo and St. Francis de Sales championed its significance, reinforcing its role in applying the canons of the Catholic Reformation. The Shroud's influence was further amplified through literature, including the publication of sermons that, while often initiated by dynastic interests, delved into theological and pastoral perspectives. A notable example is the sermons of Camillo Balliani, a Dominican and Inquisitor of Turin, who was committed to upholding correct doctrine and promoting the Council's directives. Alongside these theological works, devotional prints featuring the Shroud, accompanied by prayers, became popular. These prints served as aids for meditation and as introductions to the mystery of salvation represented by the Shroud. Another significant method of dissemination were full-sized copies or scaled-down versions of the Shroud on canvas. These replicas, prevalent from the 16th to the 19th centuries, were often produced for solemn expositions. The Savoy family used these copies as prestigious gifts for kings, foreign ambassadors, and apostolic nuncios, employing them strategically to strengthen dynastic ties established through matrimonial and military alliances.

However, these political and diplomatic practices only partly capture the essence of replicating the Shroud. Creating a copy was seen as an act of engaging with the mystery of the Shroud, transcending mere practical or secular purposes to attain a deeply religious dimension. The process of replicating the Shroud was not just an artistic endeavor commissioned by the Prince; it was a sacred act that brought the artist's eye and hand into close contact with the image of Christ, necessitating spiritual awareness and preparation. This reverence is exemplified by the ritual prescribed by Emanuele Filiberto for creating a copy for Philip II. The Shroud was displayed in a private chapel, illuminated by numerous chandeliers and lamps. While the royal painter worked on the replica, kneeling and with an uncovered head, pious clergymen recited the prayer of the forty hours. This solemn process was intended to ensure respect and devotion during the replication, contrasting with previous instances where painters approached the task casually and subsequently encountered misfortune, believed to be a sign of divine displeasure. This anecdote, detailed in Bonafamiglia's "La Sacra historia della Santissima Sindone," highlights the profound respect and solemnity accorded to the task of reproducing the Shroud's image.

The replication of the Holy Shroud of Turin involved a unique ritualistic process, where copies were often physically placed against the original Shroud. This act was believed to transfer some of the Shroud's sacredness to the copies, allowing them to partake in and convey the mystery the Shroud represents.

These authorized and certified copies are highly valued, as not all replicas can claim direct lineage from the original due to the absence of objective verification. Around these copies, various stories, including tales of fraudulent productions or miraculous occurrences, have emerged, adding to local folklore. In some communities, these replicas of the Shroud have been integrated into official liturgical practices, particularly on Good Friday, and into various devotional forms developed by popular piety, such as the Entierro rite, mysteries, and penitential processions. Special brotherhoods have even been established to oversee the care and devotion to these copies. The oldest known copy of the Shroud dates back to 1516, currently preserved in Lierre, Belgium. While few copies bear the artist's signature, many include inscriptions affirming their resemblance to the original in Turin or come with documents of authentication, other writings, or dedications. These copies are often adorned with intricate borders and ornaments. One notable example is the copy believed to have been received by Charles Borromeo from the Bishop of Vercelli, Carlo Francesco Bonomi. Borromeo venerated this copy in his private chapel, making it a Borromean relic in its own right. Additionally, princesses Maria Apollonia and Francesca Caterina, daughters of Charles Emmanuel I and declared venerable in 1838, were known for their devotion to the Shroud. During their travels, they carried copies of the original and presented them as gifts to their hosts. Interestingly, the characteristic of the original Shroud behaving like a photographic negative was not understood during the peak period of these copies' production. This feature was only discovered after the first photograph of the Shroud was taken by Secondo Pia in 1898. Pia's subsequent attempt to photograph a reproduction of the 1670 painting by Count Gay of Montariolo revealed that these copies lacked the original's negative-like quality. Not all copies were likely made directly from the Shroud but rather using preparatory drawings or sketches. This could account for certain discrepancies between the copies and the original, often seen in groups of replicas from specific periods. These painted copies of the Shroud hold significant historical and documentary value. They are essential for understanding the evolution and spread of devotion to the sacred linen and its establishment in communities responsible for these revered objects.

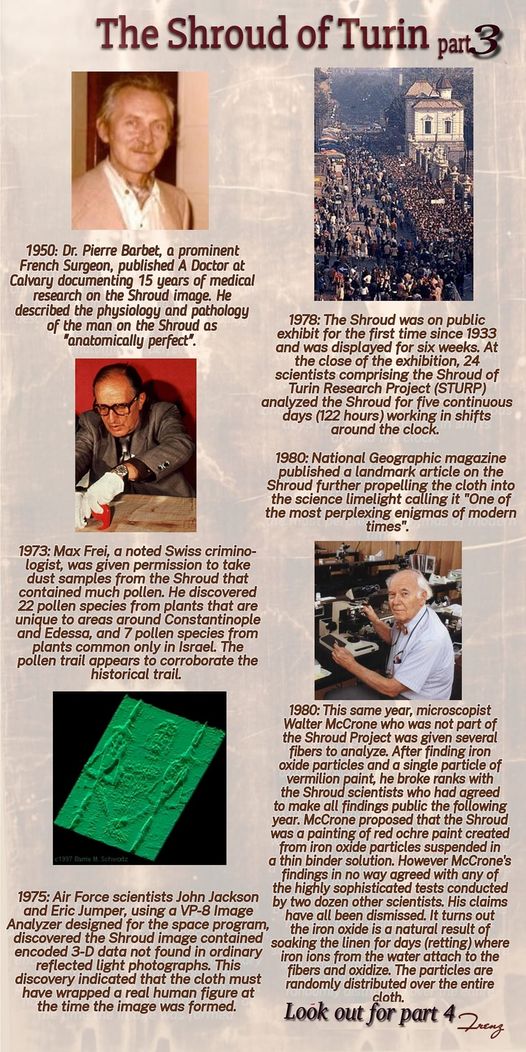

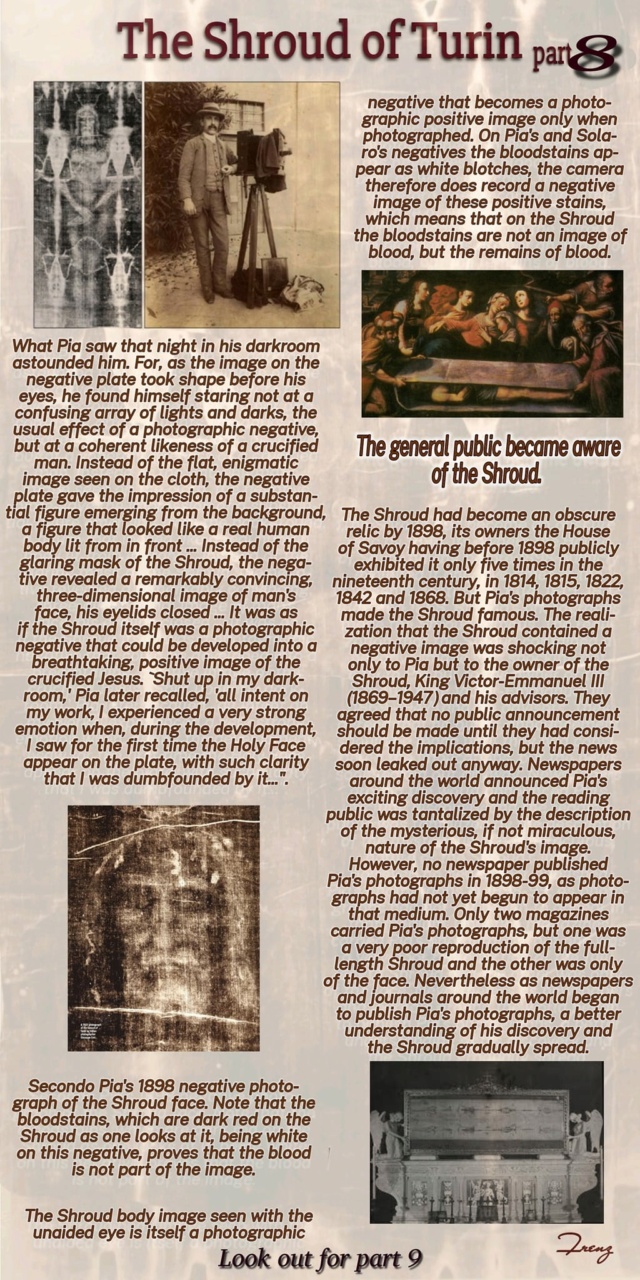

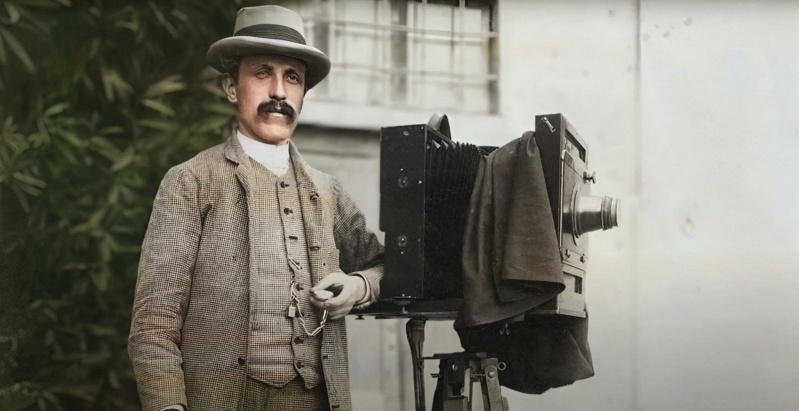

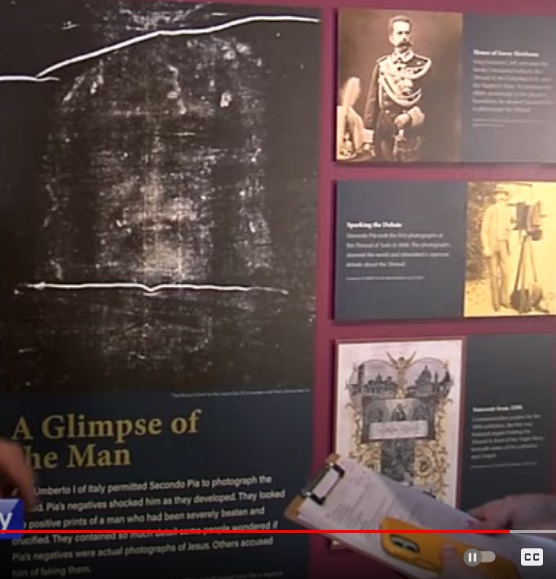

In 1898 Secondo Pia took the first official photograph of the Shroud

During the 1898 Exposition of the Shroud from 25 May to 2 June, Turin lawyer, city councillor and amateur but expert photographer, Secondo Pia (1855–1941), photographed the Shroud. Pia's first attempt to photograph the Shroud on 25 May was only partially successful. But he "managed two exposures and although they were less than perfect, already evident on these negatives was a rather strange effect".

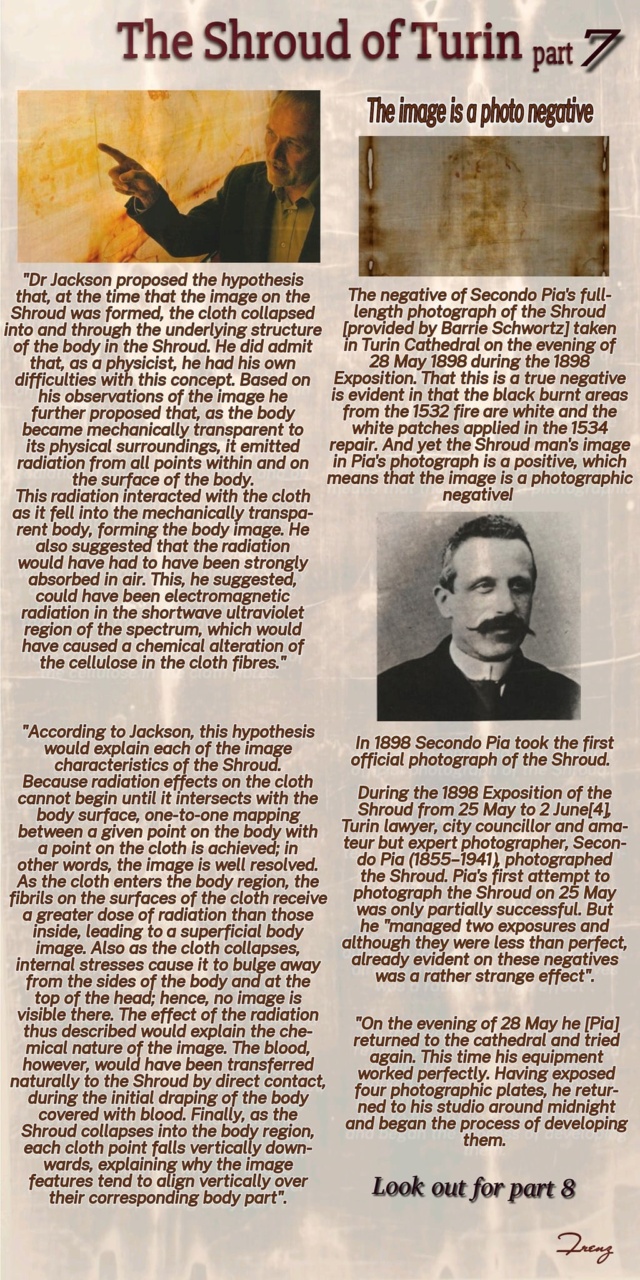

"On the evening of 28 May he [Pia] returned to the cathedral and tried again. This time his equipment worked perfectly. Having exposed four photographic plates, he returned to his studio around midnight and began the process of developing them. What Pia saw that night in his darkroom astounded him. For, as the image on the negative plate took shape before his eyes, he found himself staring not at a confusing array of lights and darks, the usual effect of a photographic negative, but at a coherent likeness of a crucified man. Instead of the flat, enigmatic image seen on the cloth, the negative plate gave the impression of a substantial figure emerging from the background, a figure that looked like a real human body lit from in front ... Instead of the glaring mask of the Shroud, the negative revealed a remarkably convincing, three-dimensional image of man's face, his eyelids closed ... It was as if the Shroud itself was a photographic negative that could be developed into a breathtaking, positive image of the crucified Jesus. `Shut up in my darkroom,' Pia later recalled, 'all intent on my work, I experienced a very strong emotion when, during the development, I saw for the first time the Holy Face appear on the plate, with such clarity that I was dumbfounded by it...".

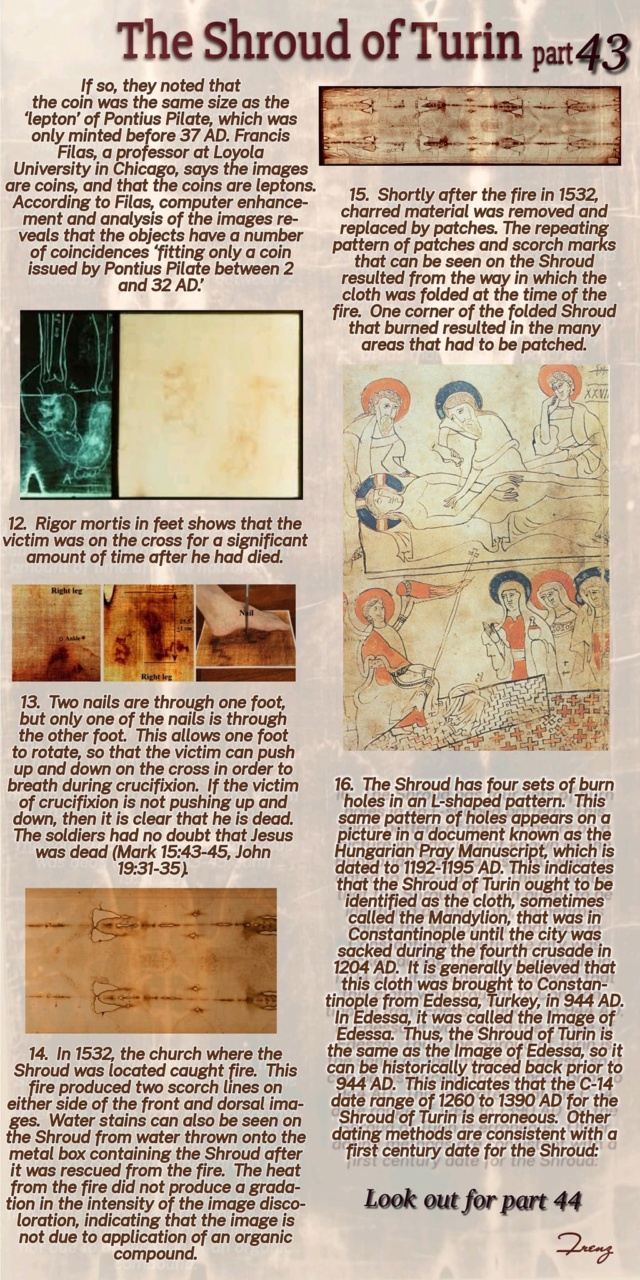

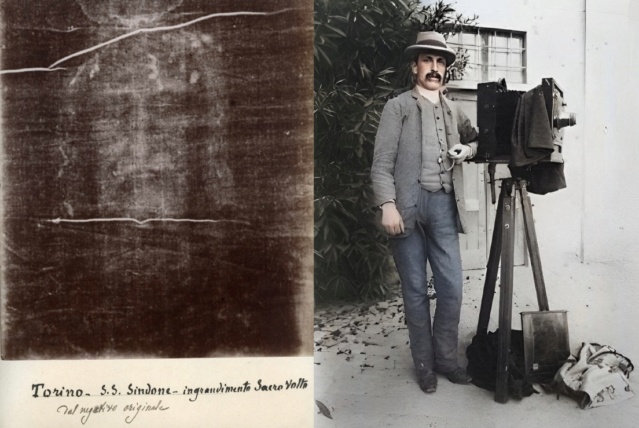

Secondo Pia's 1898 negative photograph of the Shroud face. Note that the bloodstains, which are dark red on the Shroud as one looks at it, being white on this negative, proves that the blood is not part of the image.

In the Museum of the Holy Shroud in Turin, which is located a short distance from the cathedral housing the Shroud itself, there is an antique plate camera with a precision Voigtländer lens dating back to the late nineteenth century. This camera played a pivotal role in reshaping the understanding of the Shroud's imprint in 1898. In that year, Italy was celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of its constitution, and as part of the festivities in Turin, there was a plan to publicly exhibit the Shroud. Don Nogier de Malijai, a twenty-seven-year-old Salesian priest and an enthusiastic amateur photographer, saw this as a unique opportunity to capture the Shroud's image through photography, a first of its kind. This concept wasn't entirely new, as back in 1842, during the celebration of the marriage of Savoy's Prince Victor Emmanuel, the Shroud had been displayed from the balcony of the Turin Royal Palace. At that time, a local instrument-maker named Enrico Jest had developed equipment that could replicate France's innovative daguerreotype photographic process. If the Shroud had been displayed on a brighter day and for a longer duration, Jest might have had the chance to create the very first photograph of it.

However, even half a century later, the idea of allowing the Shroud to be photographed was met with reluctance, as it was considered inappropriate for such a sacred relic. In the late 19th century, the Shroud of Turin, then owned by King Umberto I of Savoy of Italy, was a subject of great intrigue. Despite his initial reluctance, King Umberto eventually allowed an official photograph of the Shroud. This task was unexpectedly given to Secondo Pia, a 43-year-old lawyer with a passion for amateur photography, who had never seen the Shroud before. Pia faced several technical challenges during this assignment. He could only photograph the Shroud as it was displayed behind glass, above the altar in the dimly lit cathedral. The need for electric lighting, then a novel and unreliable technology, added to the complexity. Additionally, Pia had to construct a three-meter-high platform for his camera to capture the image from the appropriate angle. The first attempt to photograph the Shroud took place on May 25, 1898, but it was fraught with difficulties, including issues with the electric lamps. Despite these challenges, Pia managed two exposures. These initial photographs already hinted at an unusual effect, though they were not perfect. Pia returned on the night of May 28, accompanied by Don Nogier and Felice Fino, a cathedral security guard and fellow photography enthusiast. Starting at about 9:30 p.m., Pia conducted two trial exposures, followed by Nogier and Fino who also took some unofficial photos. For the final, official shots, Pia used a high-quality Voigtländer lens and took four exposures, each lasting between eight and fourteen minutes, but only officially recorded two of them. Later that night, in his darkroom, Pia developed the best of the four plates. Instead of the faint impressions of the Shroud's imprints, he observed an extraordinary effect. The images revealed something far more remarkable than anyone could have anticipated.

The negative images of the Shroud of Turin, captured by Secondo Pia, revealed a transformation of its enigmatic imprints. Where previously the figures appeared as indistinct shadows, difficult to interpret and often perceived as grotesque, they now exhibited clear, natural light and dark shading, adding depth and realism. The bloodstains, now white in the negative, seemed to flow authentically from the hands, feet, and around the crown of the head. The man in the Shroud, instead of appearing flat and undefined, was now seen as a well-built, proportionate figure. Most striking was the face, dignified even in death and remarkably lifelike against the dark background of the negative image. Pia felt a profound sense of history, believing he was witnessing the true appearance of Christ as he was laid in the tomb, captured in a photograph hidden within the fabric. The discovery quickly made headlines, with the first report appearing in L’Italia Reale Corriere Nazionale on June 1, followed by an unofficial photo. However, skepticism soon arose. The Italia Corriere suggested on June 15 that the effect was due to Pia using a yellow filter. Other theories proposed it was an accident of transparency, over-exposure, or refraction. More damaging were insinuations that Pia had tampered with the negative, creating a hoax. Over the next three years, even some prominent Roman Catholic churchmen expressed doubts, focusing on the Shroud's unclear historical origins before its appearance in 14th-century France. This skepticism cast a shadow over the Shroud and Pia's reputation, similar to the controversy following the 1988 radiocarbon dating. A new opportunity to examine the Shroud arose in 1931 during the wedding of Prince Umberto of Piedmont to Princess Maria José of Belgium. The event drew millions to Turin, and the Savoy family chose to display the Shroud publicly. Giuseppe Enrie, a professional Turin photographer, was appointed to take new, official photographs. Between May 21 and 23, Enrie captured a series of definitive black-and-white photographs, with the Shroud free from any protective glass, using advanced photographic equipment. He took twelve official photos, including full and sectional views of the Shroud, the complete back body imprint, and various close-ups of the face and wounds, all showcasing pre-digital-era photographic excellence. Enrie's work, especially the natural-size negative of the Shroud man's face, was highly acclaimed. The crown prince Umberto, for whom the exhibition was held, was reportedly overwhelmed with emotion upon seeing these images.

The historic glass plate is now a significant artifact housed in Turin’s Museum of the Shroud. This plate, along with thousands of other negative photographs of the Shroud's face taken over the years by both professionals and amateurs, has helped to dispel any lingering notions that the phenomenon first revealed by Secondo Pia in 1898 was a hoax. Remarkably, Pia, then aged seventy-six, lived to see his work vindicated. He was invited to witness the exhibition along with a public notary and photographic experts, ensuring that Giuseppe Enrie's process was free from any deception.

Four decades later, in 1973, Pope Paul VI expressed his profound reaction to Enrie’s photograph of the Shroud, which he first saw as a young priest in 1931. During a televised address accompanying the Shroud's first color television broadcast, he described the image as strikingly authentic and deeply moving, possessing both human and divine qualities unmatched by any other image. Similarly, Leo Vala, a well-known London photographer and self-professed agnostic, praised the image in a photographic journal in the same decade. Vala, experienced in various visual processes, attested to the authenticity of the Shroud's image, asserting that it could not have been fabricated with any contemporary technology, highlighting its precise photographic quality and the perfection of its negative.

http://www.acheiropoietos.info/proceedings/LavoieWeb.pdf

https://flora.org.il/books/turin/

Shroud Expositions in recent times

1898

In a landmark moment for both history and science, a breakthrough in technology enabled the first successful photographic capture of the enigmatic Holy Shroud. The images were the work of Secondo Pia, not a professional but a fervently dedicated amateur photographer. Accounts from that era depict the Shroud bathed in electric light, creating a spectacle of extraordinary magnificence. This remarkable exhibition, which ran from May 25 to June 2, drew crowds to Turin at an astounding rate of 25,000 daily visitors, a staggering feat considering the limited transportation infrastructure of the late 19th century. As Pia processed his photographs, he was struck by the profound significance of his endeavor. He confided to his assistant that, alone in the darkroom, the sight of the sacred visage emerging on the plate overwhelmed him with such a potent mix of astonishment and elation. That year's display of the Shroud marked the high point of a series of significant milestones for the city, including the 400th anniversary of the cathedral's completion, the 300th year since the founding of the Confraternity of the Holy Shroud, and the half-century mark of the Albertine Statute.

1931:

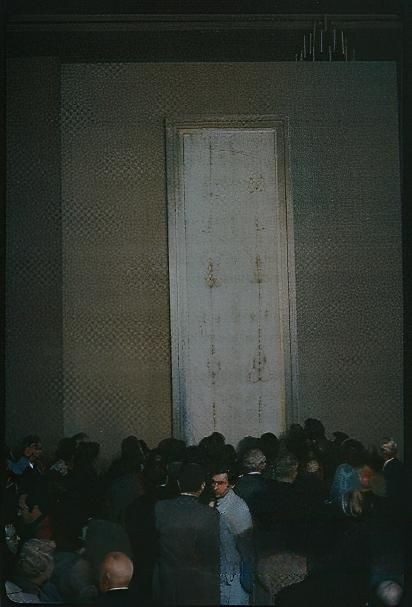

In 1931, a grand exhibition in Turin celebrated the nuptials of Prince Umberto II of Savoy and Princess Maria José of Belgium. The majestic Duomo of Turin played host to not just scores of pilgrims but also an assembly of nobility and clergy, making for a grand public spectacle. The air buzzed with anticipation as many had journeyed to witness the splendor of the royal court. Newspaper headlines heralded an unparalleled procession, a cavalcade of knights, soldiers, and clerics, arrayed in their most ornate uniforms. The scene was one to behold, with throngs of pilgrims thronging the Duomo's steps, orderly managed by a robust security detail, as the devout trickled in from every direction, by foot and by carriage. The event, commencing on the 3rd of May, was a magnet for the masses, drawn to the rare public display of the Shroud from the cathedral's grilles. To accommodate the overwhelming turnout, the sacred relic was exhibited in this manner throughout. Spanning a fortnight, the exhibition was a Papal decree by Pope Pius XI, Achille Ratti, to mark the extraordinary Holy Year and the nineteen centuries since the Christian narrative of redemption. The opening day was a gathering of monarchs and the clergy, with the presence of five queens, a cardinal, and numerous bishops, as reported by the press. The cathedral was bathed in radiance, the holy linen veiled under a colossal cover. Notably striking was the sight of crutches abandoned by those who had been healed, a testament to the sanctity of the event. These were prominently displayed on June 6th, a testament from devotees hailing from Switzerland, Spain, France, and Ireland. The newspapers painted a vivid picture of the international crowd, unprecedented in its diversity. Tokens left by the Italian faithful bore the names of their hometowns, a poignant touch to the miracle-woven narrative. The humeral veil, initially presented to the gathered multitudes in Piazza San Giovanni, was later elevated by the bishops and paraded down the main aisle in a solemn procession. It was a moment of profound reverence, punctuated by the pealing of the Duomo's bells, quickly echoed by the tolling from across the city.

1969

Between the 16th and 18th of June, the revered Shroud was displayed within the hallowed confines of the Royal Palace's Chapel of the Holy Shroud. This display was not just for public veneration but also for a meticulous examination by a study committee, overseen by Cardinal Michele Pellegrino. The fabric was subject to a battery of photographic techniques, this time using color imagery, under the expert guidance of Giovanni Battista Judica Cordiglia, who was tasked with the official photographic reproduction. The photographic endeavor was comprehensive, employing various lighting conditions, including normal and infrared light, to capture and elucidate as many details as possible from both the fabric and the enigmatic image it bore. These photographs, preserved to this day, serve as a testament to this detailed analysis. Giovanni Battista Judica Cordiglia, not only an esteemed member of the Commission but also an acknowledged photographer, was specifically called upon due to a provocative hypothesis put forth by Kurt Berna, the president of Switzerland's 'Foundation of the Holy Shroud.' Berna, claiming a close friendship with Cordiglia, promulgated pamphlets bearing his controversial theory: that the Shroud had enfolded not the remains of the deceased, but a body that was still alive.

1973

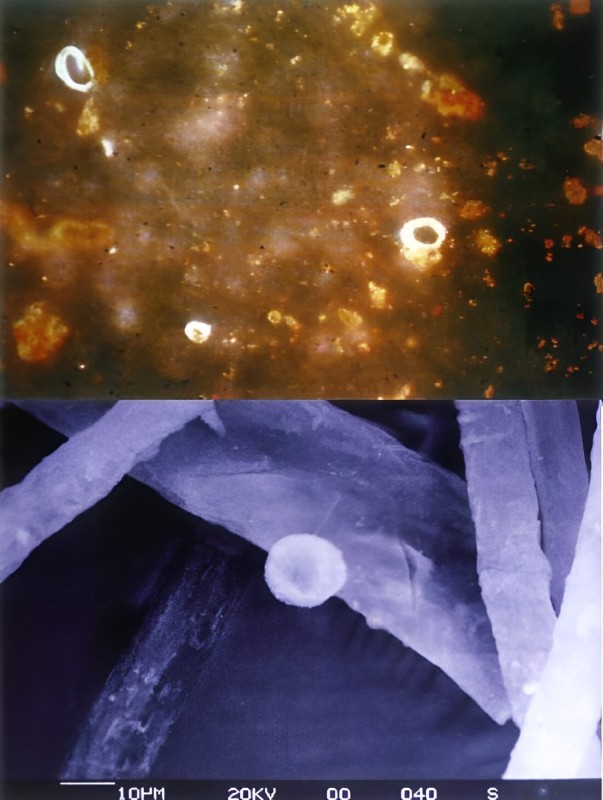

The exhibition marked a historic milestone as it became the first ever to be broadcast via television. Millions of individuals watched from the comfort of their homes, while thousands of devout followers gathered in the hall of the Swiss at the Royal Palace in Turin. In a break from tradition and to facilitate the television broadcast, the Shroud was displayed vertically rather than in the horizontal orientation that had been customary until then. The live transmission, showcasing what is believed to be the image of Jesus, was initiated abruptly following scholarly studies. As reported by Ugo Buzzolan of 'La Stampa', who is recognized as a pioneer in television criticism, this strategic approach was adopted because, during the initial official display, a small fragment of the Shroud's fabric was sampled. This was done in order to conduct analyses on the material present on the fabric and to examine the numerous particles embedded within the linen's weave. Among the microtraces discovered, particularly notable were the pollen grains, meticulously identified by Swiss biologist Max Frei Sulzer, who was the head of the Zurich Scientific Police. His studies revealed the presence of over fifty distinct pollen types.

1978

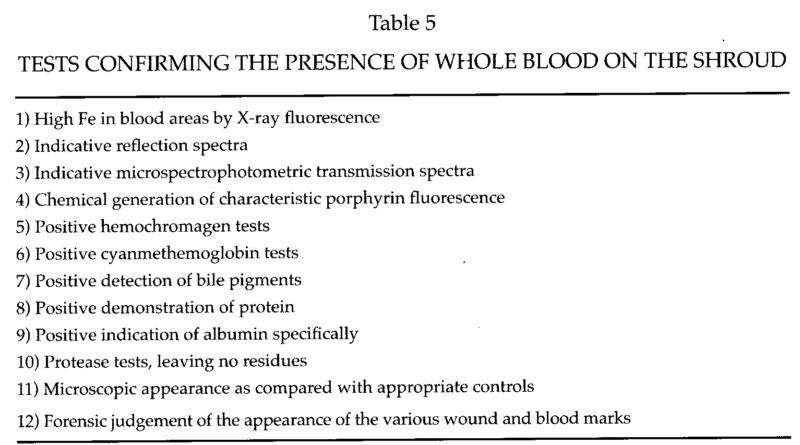

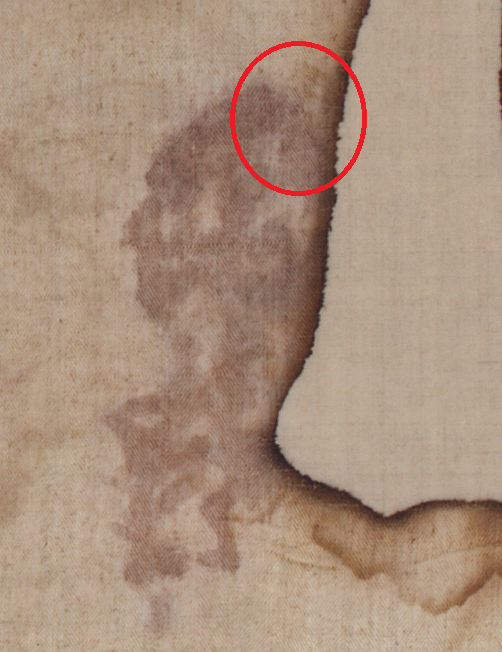

In a moment of profound synchronicity for those of the Catholic faith, a remarkable event unfolded on August 27, 1978. It was the day following the appointment of the 264th pontiff, Albino Luciani of Venice, who took the papal name John Paul I. This was also when the venerated Shroud underwent a public display, marking 400 years since its relocation from Chambéry to Turin, a ceremonial exhibition that drew over three million pilgrims to the city over a span of forty-two days. Following the period of public veneration, an international cohort of over two hundred scholars, along with the esteemed president of the Tribunal and the director of Turin's International Center of Sindonology, embarked on a meticulous examination of the Shroud's fabric, particularly areas marked by blood. Their investigations yielded findings consistent with human biochemistry, noting the presence of calcium, protein, and iron in proportions typical of the human constitution, further determining the blood type to be AB.

1998

At the dawn of the Internet age, a significant event marked the close of the second millennium: the final exhibition of the Shroud and the inaugural online transmission of the Holy Mass led by Pope John Paul II in the Duomo. This event also commemorated the 100th anniversary of Secondo Pia's pioneering photograph of the Holy Shroud. Over the course of forty-five days, Turin became a focal point for over 1.5 million individuals, including pilgrims, the inquisitive, and the scientific community, who came to witness and scrutinize the relic. Despite extensive analysis, a consensus on the Shroud's authenticity remained elusive. The preservation of the Shroud was enhanced by innovative means: encased in a dual-layered, five-millimeter-thick acrylic, with a small gap of air in between for protection, and an inner layer made of a resilient acrylic material. A specialized crystal overlay, designed to be anti-reflective and to shield against ultraviolet light, ensures the safeguarding of the fabric. Henceforth, the revered image on the Shroud, known as the Holy Face, will be securely displayed within this protective enclosure.

2000

The turn-of-the-millennium exhibition, orchestrated just a couple of years after its predecessor, was a heartfelt wish of Pope John Paul II, coinciding with the Jubilee, a significant event in Catholicism symbolizing forgiveness and spiritual renewal. This display made history not only for its unprecedented 72-day duration but also for its groundbreaking presentation: it marked the first use of a specialized aluminum case with slats, providing a new way for the public to view the mysterious image on the Shroud. As devotees made their pilgrimage from the Royal Gardens to the Cathedral, kneelers were thoughtfully provided along the path to invite moments of reflection and prayer. Despite the past adversity of a fire in the Guarini Chapel, the city proved its resilience, successfully hosting over two and a half million visitors. Turin was lauded for its exemplary management; throughout this extensive period, no untoward events occurred. Local businesses participated wholeheartedly, ensuring continuous service during the late August sales, while the city administration adeptly catered to every need of the vast crowds, offering an array of services including transportation, information booths, accommodations, and community dining experiences.

Shroud Exposition in Germany:

https://www.malteser-turinergrabtuch.de/literatur.html

Last edited by Otangelo on Wed Jan 17, 2024 7:20 am; edited 17 times in total

[/font

[/font