Ottoia - priapulid worms from the Cambrian

http://reasonandscience.heavenforum.org/t2666-ottoia-priapulid-worms-from-the-cambrian

Ottoia is a stem-group archaeopriapulid worm known from Cambrian fossils. Although priapulid-like worms from various Cambrian deposits are often referred to Ottoia on spurious grounds, the only clear Ottoia macrofossils come from the Burgess Shale of British Columbia, which was deposited 508 million years ago.[1] Microfossils extend the record of Ottoia throughout the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin, from the mid- to late- Cambrian. 2

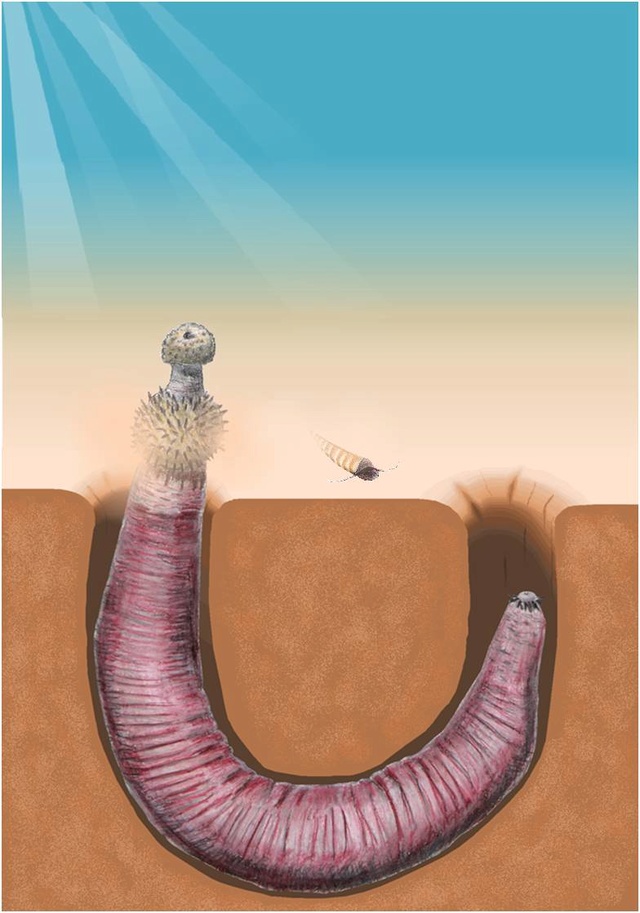

Ottoia is a priapulid worm with a tooth-lined mouthpart (proboscis) that could be inverted into the trunk; a short posterior tail extension could also be inverted. Ottoia reached 15 cm in length; the smallest specimens – presumably juveniles, but identical to adults – were just 1 cm long. The proboscis was adorned with 28 rows of hooks interspersed with a variety of spines. The worms are usually found curved into a U-shape, with their sediment-filled guts often visible running down the centre of the organism. The trunk was annulated, and bore two sets of four hooks arranged in a ring towards the rear end; these are the only traces of bilateral symmetry, with a radial symmetry superimposed on the organism. Ottoia periodically shed its cuticle to allow growth. 4

This 505-million-year-old phallus-like creature actually had a throat full of teeth. 5

Now, scientists who took a close look at the teeth of fossilized penis worms (or priapulids) have discovered a new species.

This fossil shows the new species, Ottoia tricuspida.

At just a few inches long, O. prolifica lived inside burrows and had a proboscis that was lined with rows of little hooks, teeth and spines. This mouthpart could be inverted into the creature's trunk (as this animation from the Royal Ontario Museum shows), and it allowed O. prolifica to feast on shelled creatures known as hyolithids (although O. prolifica may also have occasionally cannibalized other penis worms), according to the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

In a new report, researchers led by Martin Smith of the University of Cambridge in England created a "dentist's handbook" of O. prolifica teeth. Under a microscope, they looked at 40 O. prolifica fossils from a location called the Upper Walcott Quarry that are now in a collection at the Smithsonian Institution, and 70 other specimens from the Lower Walcott Quarry that are housed in the Royal Ontario Museum.

The researchers found some unexpected differences between the teeth in the two groups of fossils. For example, the specimens from the Lower Walcott Quarry had some teeth with a central prong that was flanked by just two skinny, hollow "denticles," whereas up to eight denticles were common in the corresponding teeth of the Upper Walcott Quarry specimens.

Paleontologist Charles Walcott first discovered O. prolifica in 1911 in the Burgess Shale, a geologic formation in the Canadian Rockies that contains fossils of bizarre critters, such as trilobites and velvet worms, from the middle Cambrian period.

The most abundant type of creature preserved in the Burgess Shale is a type of worm, a member of the Phylum Priapulidae and now thanks to a detailed study of the teeth, hooks and spines on this tubular predator, scientists have discovered a method of identifying new species and also of determining just how abundant these creatures actually may have been. 3

Ottoia fossils from the Burgess Shale of British Columbia (Canada), measure just a few centimetres in length and they are one of the few types of creature preserved in those 5o5 million year old sediments that can be associated with a living animal group, the entirely marine priapulids. At least fifteen hundred specimens have been excavated from the Burgess Shale deposits. These creatures may have lived in “U” shaped burrows and ambushed other creatures that wandered or swam to close to the burrow’s entrance. It could grab food with a proboscis, an extendible mouth which was equipped with tiny hooks and lined with teeth and spines. The team of scientists from Cambridge University and the University of Leicester, writing in the on line Journal “Palaeontology” used a variety of techniques to examine micro-fossils to identify different types of teeth from Ottoia It is from this analysis that the team discovered that the most common type of priapulid associated with the Burgess Shale, Ottoia prolifica, actually represented two species.

As a result of this research, a new species of Ottoia worm has been identified in the Burgess Shale deposits – Ottoia tricuspida. O. tricuspida has been so named as it has distinctive, three-pronged teeth. Using various microscopy techniques to examine the tiny teeth recovered from drill cores and from other samples, the scientists propose that subtle variations in the teeth could help to identify more species in Cambrian biota and in addition, as the teeth are more likely to be preserved than the soft bodies of these creatures, the teeth could help to establish how widespread such worms were in the Cambrian geological period.

Ottoia prolifica was named by Charles Doolittle Walcott in 1911. Walcott, an American invertebrate palaeontologist, discovered the Burgess Shale deposits in the Canadian Rockies back in 1909. These bands of mudstone and shale are very rich in fossils. The frequency of Ottoia fossil material might not be anything to do with the abundance of these types of animals in the biota, the numbers found could reflect the fact that these animals lived in soft sediment. If one of these worms died in their burrow, then they could set in motion the fossilisation process. The soft mud would act as an excellent medium to promote the preservation of creatures that lived in the sediment.

Ancient flesh-eating ‘penis worm’ dragged itself around by teeth 6

Carnivorous penis-shaped worms could turn their mouths inside out and drag themselves along by their teeth during the Cambrian Period, 500 million years ago

It sounds like something out of a Frank Herbert fantasy novel, but flesh-eating ‘penis worms’ roamed the Earth 500 million years ago.

The creature was able to turn its mouth inside out and use its tooth-lined throat – which resembled a cheese grater – to drag itself around the Cambrian world.

Unlike the monsters in Herbert’s novel Dune, these creatures were only the size of a finger, and lived in burrows under the sea.

However they were voracious predators, gobbling up anything that crossed their path, including worms, shrimp and other marine creatures.

The phallic-shaped animals, officially known as priapulids, emerged during the ‘Cambrian explosion’, a period of rapid evolutionary development about half a billion years ago, when most major animal groups first appear in the fossil record.

Scientists at the University of Cambridge have been studying fossil remains of their teeth to work out how far penis worms spread across the world

During the Cambrian, most animals were soft-bodied, like worms and sponges. Therefore, outside of the few very special places where conditions are just right to enable preservation of soft-bodied creatures, it is difficult to know for certain how far certain species were distributed.

The teeth of the ‘penis worms’ had different shapes according to their function: some were shaped like a cone fringed with tiny prickles and hairs, some were shaped like a bear claw, and some like a city skyline.

But they are so tiny that they had previously been misidentified as spores. Now that the teeth can be identified, it proves that the worms inhabited certain areas.

“As teeth are the most hardy and resilient parts of animals, they are much more common as fossils than whole soft-bodied specimens,” said Dr Martin Smith, a postdoctoral researcher in Cambridge’s Department of Earth Sciences and the paper’s lead author.

“But when these teeth – which are only about a millimetre long – are found, they are easily misidentified as algal spores, rather than as parts of animals. Now that we understand the structure of these tiny fossils, we are much better placed to a wide suite of enigmatic fossils.”

Penis worms still exist today and live in the sediment of ocean beds.

These teeth were not just used for eating food, however. By turning their mouths inside out, penis worms could also use their teeth sort of like miniature grappling hooks, using them to grip a surface and then pull the rest of their bodies along behind.

“Modern penis worms have been pushed to the margins of life, generally living in extreme underwater environments,” added Dr Smith. “But during the Cambrian, they were fearsome beasts, and extremely successful ones at that.”

For this study, the researchers examined fossils of Ottoia, a type of penis worm, about the length of a finger, which lived during the Cambrian.

The fossils originated from the Burgess Shale in Western Canada, the world’s richest source of fossils from the period.

Using high resolution electron and optical microscopy, they were able to expose the curious structure of Ottoia’s teeth for the first time.

By reconstructing the structure of these teeth in detail, the researchers were then able to identify fossilised teeth of a number of previously-unrecognised penis worm species from all over the world.

“Teeth hold all sorts of clues, both in modern animals and in fossils,” said Dr Smith.

“It’s entirely possible that unrecognised species await discovery in existing fossil collections, just because we haven’t been looking closely enough at their teeth, or in the right way.”

1. http://www.lifebeforethedinosaurs.com/2011/06/ottoia.html

2. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ottoia

3. https://blog.everythingdinosaur.co.uk/blog/_archives/2015/05/09/it-was-a-worms-world-back-in-the-cambrian.html

4. http://burgess-shale.rom.on.ca/en/fossil-gallery/view-species.php?id=95

5. https://www.livescience.com/50748-cambrian-penis-worm-discovered.html

6. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/11582988/Ancient-flesh-eating-penis-worm-dragged-itself-around-by-teeth.html

http://reasonandscience.heavenforum.org/t2666-ottoia-priapulid-worms-from-the-cambrian

Ottoia is a stem-group archaeopriapulid worm known from Cambrian fossils. Although priapulid-like worms from various Cambrian deposits are often referred to Ottoia on spurious grounds, the only clear Ottoia macrofossils come from the Burgess Shale of British Columbia, which was deposited 508 million years ago.[1] Microfossils extend the record of Ottoia throughout the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin, from the mid- to late- Cambrian. 2

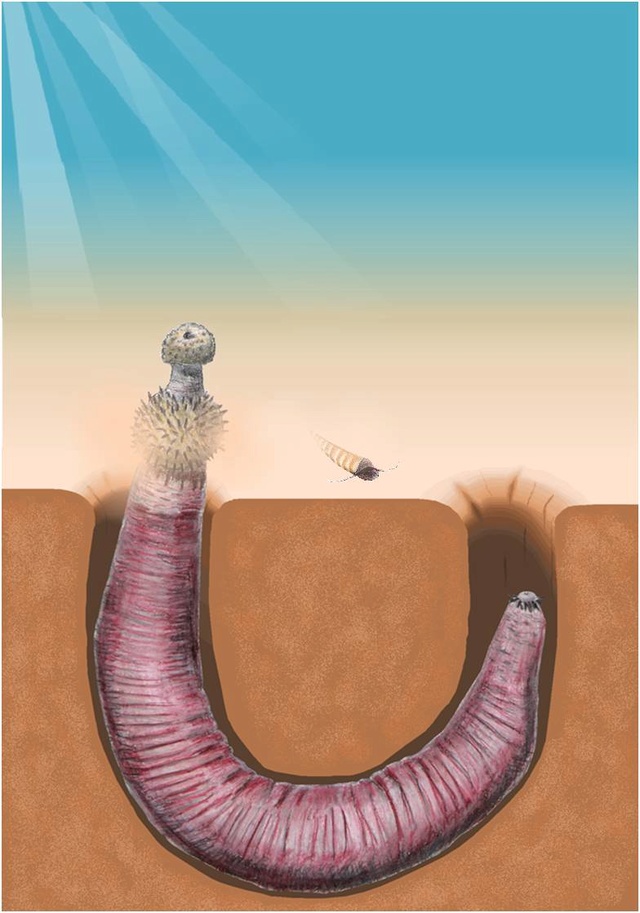

Ottoia is a priapulid worm with a tooth-lined mouthpart (proboscis) that could be inverted into the trunk; a short posterior tail extension could also be inverted. Ottoia reached 15 cm in length; the smallest specimens – presumably juveniles, but identical to adults – were just 1 cm long. The proboscis was adorned with 28 rows of hooks interspersed with a variety of spines. The worms are usually found curved into a U-shape, with their sediment-filled guts often visible running down the centre of the organism. The trunk was annulated, and bore two sets of four hooks arranged in a ring towards the rear end; these are the only traces of bilateral symmetry, with a radial symmetry superimposed on the organism. Ottoia periodically shed its cuticle to allow growth. 4

This 505-million-year-old phallus-like creature actually had a throat full of teeth. 5

Now, scientists who took a close look at the teeth of fossilized penis worms (or priapulids) have discovered a new species.

This fossil shows the new species, Ottoia tricuspida.

At just a few inches long, O. prolifica lived inside burrows and had a proboscis that was lined with rows of little hooks, teeth and spines. This mouthpart could be inverted into the creature's trunk (as this animation from the Royal Ontario Museum shows), and it allowed O. prolifica to feast on shelled creatures known as hyolithids (although O. prolifica may also have occasionally cannibalized other penis worms), according to the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

In a new report, researchers led by Martin Smith of the University of Cambridge in England created a "dentist's handbook" of O. prolifica teeth. Under a microscope, they looked at 40 O. prolifica fossils from a location called the Upper Walcott Quarry that are now in a collection at the Smithsonian Institution, and 70 other specimens from the Lower Walcott Quarry that are housed in the Royal Ontario Museum.

The researchers found some unexpected differences between the teeth in the two groups of fossils. For example, the specimens from the Lower Walcott Quarry had some teeth with a central prong that was flanked by just two skinny, hollow "denticles," whereas up to eight denticles were common in the corresponding teeth of the Upper Walcott Quarry specimens.

Paleontologist Charles Walcott first discovered O. prolifica in 1911 in the Burgess Shale, a geologic formation in the Canadian Rockies that contains fossils of bizarre critters, such as trilobites and velvet worms, from the middle Cambrian period.

The most abundant type of creature preserved in the Burgess Shale is a type of worm, a member of the Phylum Priapulidae and now thanks to a detailed study of the teeth, hooks and spines on this tubular predator, scientists have discovered a method of identifying new species and also of determining just how abundant these creatures actually may have been. 3

Ottoia fossils from the Burgess Shale of British Columbia (Canada), measure just a few centimetres in length and they are one of the few types of creature preserved in those 5o5 million year old sediments that can be associated with a living animal group, the entirely marine priapulids. At least fifteen hundred specimens have been excavated from the Burgess Shale deposits. These creatures may have lived in “U” shaped burrows and ambushed other creatures that wandered or swam to close to the burrow’s entrance. It could grab food with a proboscis, an extendible mouth which was equipped with tiny hooks and lined with teeth and spines. The team of scientists from Cambridge University and the University of Leicester, writing in the on line Journal “Palaeontology” used a variety of techniques to examine micro-fossils to identify different types of teeth from Ottoia It is from this analysis that the team discovered that the most common type of priapulid associated with the Burgess Shale, Ottoia prolifica, actually represented two species.

As a result of this research, a new species of Ottoia worm has been identified in the Burgess Shale deposits – Ottoia tricuspida. O. tricuspida has been so named as it has distinctive, three-pronged teeth. Using various microscopy techniques to examine the tiny teeth recovered from drill cores and from other samples, the scientists propose that subtle variations in the teeth could help to identify more species in Cambrian biota and in addition, as the teeth are more likely to be preserved than the soft bodies of these creatures, the teeth could help to establish how widespread such worms were in the Cambrian geological period.

Ottoia prolifica was named by Charles Doolittle Walcott in 1911. Walcott, an American invertebrate palaeontologist, discovered the Burgess Shale deposits in the Canadian Rockies back in 1909. These bands of mudstone and shale are very rich in fossils. The frequency of Ottoia fossil material might not be anything to do with the abundance of these types of animals in the biota, the numbers found could reflect the fact that these animals lived in soft sediment. If one of these worms died in their burrow, then they could set in motion the fossilisation process. The soft mud would act as an excellent medium to promote the preservation of creatures that lived in the sediment.

Ancient flesh-eating ‘penis worm’ dragged itself around by teeth 6

Carnivorous penis-shaped worms could turn their mouths inside out and drag themselves along by their teeth during the Cambrian Period, 500 million years ago

It sounds like something out of a Frank Herbert fantasy novel, but flesh-eating ‘penis worms’ roamed the Earth 500 million years ago.

The creature was able to turn its mouth inside out and use its tooth-lined throat – which resembled a cheese grater – to drag itself around the Cambrian world.

Unlike the monsters in Herbert’s novel Dune, these creatures were only the size of a finger, and lived in burrows under the sea.

However they were voracious predators, gobbling up anything that crossed their path, including worms, shrimp and other marine creatures.

The phallic-shaped animals, officially known as priapulids, emerged during the ‘Cambrian explosion’, a period of rapid evolutionary development about half a billion years ago, when most major animal groups first appear in the fossil record.

Scientists at the University of Cambridge have been studying fossil remains of their teeth to work out how far penis worms spread across the world

During the Cambrian, most animals were soft-bodied, like worms and sponges. Therefore, outside of the few very special places where conditions are just right to enable preservation of soft-bodied creatures, it is difficult to know for certain how far certain species were distributed.

The teeth of the ‘penis worms’ had different shapes according to their function: some were shaped like a cone fringed with tiny prickles and hairs, some were shaped like a bear claw, and some like a city skyline.

But they are so tiny that they had previously been misidentified as spores. Now that the teeth can be identified, it proves that the worms inhabited certain areas.

“As teeth are the most hardy and resilient parts of animals, they are much more common as fossils than whole soft-bodied specimens,” said Dr Martin Smith, a postdoctoral researcher in Cambridge’s Department of Earth Sciences and the paper’s lead author.

“But when these teeth – which are only about a millimetre long – are found, they are easily misidentified as algal spores, rather than as parts of animals. Now that we understand the structure of these tiny fossils, we are much better placed to a wide suite of enigmatic fossils.”

Penis worms still exist today and live in the sediment of ocean beds.

These teeth were not just used for eating food, however. By turning their mouths inside out, penis worms could also use their teeth sort of like miniature grappling hooks, using them to grip a surface and then pull the rest of their bodies along behind.

“Modern penis worms have been pushed to the margins of life, generally living in extreme underwater environments,” added Dr Smith. “But during the Cambrian, they were fearsome beasts, and extremely successful ones at that.”

For this study, the researchers examined fossils of Ottoia, a type of penis worm, about the length of a finger, which lived during the Cambrian.

The fossils originated from the Burgess Shale in Western Canada, the world’s richest source of fossils from the period.

Using high resolution electron and optical microscopy, they were able to expose the curious structure of Ottoia’s teeth for the first time.

By reconstructing the structure of these teeth in detail, the researchers were then able to identify fossilised teeth of a number of previously-unrecognised penis worm species from all over the world.

“Teeth hold all sorts of clues, both in modern animals and in fossils,” said Dr Smith.

“It’s entirely possible that unrecognised species await discovery in existing fossil collections, just because we haven’t been looking closely enough at their teeth, or in the right way.”

1. http://www.lifebeforethedinosaurs.com/2011/06/ottoia.html

2. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ottoia

3. https://blog.everythingdinosaur.co.uk/blog/_archives/2015/05/09/it-was-a-worms-world-back-in-the-cambrian.html

4. http://burgess-shale.rom.on.ca/en/fossil-gallery/view-species.php?id=95

5. https://www.livescience.com/50748-cambrian-penis-worm-discovered.html

6. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/11582988/Ancient-flesh-eating-penis-worm-dragged-itself-around-by-teeth.html