Paley's watchmaker argument

https://reasonandscience.catsboard.com/t2608-paley-s-watchmaker-argument

William Paley’s “watch” argument. Basically, this argument says that after seeing a watch, with all its intricate parts, which work together in a precise fashion to keep time, one must deduce that this piece of machinery has a creator, since it is far too complex to have simply come into being by some other means, such as evolution. The skeleton of the argument is as follows:

1.Human artifacts are products of intelligent design; they have a purpose.

2.The universe resembles these human artifacts.

3.Therefore: It is probable that the universe is a product of intelligent design, and has a purpose.

4. However, the universe is vastly more complex and gigantic than a human artifact is.

5. Therefore: There is probably a powerful and vastly intelligent designer who created the universe. 1

Hume suggests that in cases where we justifiably infer from the existence of some phenomenon that a certain kind of cause must have existed, we do so on the basis of an observed pattern of correlations:

Objection: The great sceptic David Hume disposed of this sort of wishful analogical thinking nearly 250 years ago. Anyone trotting out this argument would do well to read him first before pole vaulting to untenable conclusions.

Response: Hume proposed that the universe "reproduced". His unstated assumption was that the universe did always exist ( which was the predominant view in his time) and produces "worlds" through some kind of seeding process. In fact, we know that the universe began to exist and started with the Big Bang. David Hume objected to the analogy that the universe looked like a watch, since he assumed that there was no evidence for design. However, this assumption was also based upon ignorance. Hume did not know that the universe is a finely crafted masterpiece, and that even minor changes to the laws of physics would result in a universe that didn't even contain matter! So, Hume's main argument turns out to be completely wrong.

Here is Hume's "cosmology":

In like manner as a tree sheds its seeds into the neighbouring fields, and produces other trees; so the great vegetable, the world, or this planetary system, produces within itself certain seeds, which, being scattered into the surrounding chaos, vegetate into new worlds. A comet, for instance, is the seed of a world; and after it has been fully ripened, by passing from sun to sun, and star to star, it is at last tossed into the unformed elements which every where surround this universe, and immediately sprouts up into a new system.

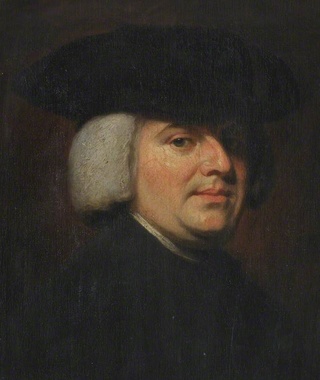

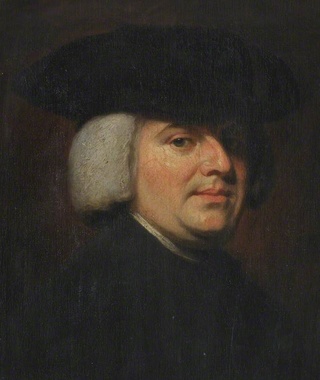

William Paley (July 1743 – 25 May 1805) was an English clergyman, Christian apologist, philosopher, and utilitarian. He is best known for his natural theology exposition of the teleological argument for the existence of God in his work Natural Theology or Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity, which made use of the watchmaker analogy. 1

I love analogies, and Paleys watchmaker analogy is a classic:

In WILLIAM PALEY's book :

Natural Theology or Evidence of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity, collected from the appearances of nature 2, page 46, he writes :

In crossing a heath, suppose I pitched my foot against a stone, and were asked how the stone came to be there, I might possibly answer, that, for any thing I knew to the contrary, it had lain there for ever: nor would it perhaps be very easy to shew the absurdity of this answer. But suppose I had found a watch* upon the ground, and it should be enquired how the watch happened to be in that place, I should hardly think of the answer which I had before given, that, for any thing I knew, the watch might have always been there. Yet why should not this answer serve for the watch, as well as for the stone? Why is it not as admissible in the second case, as in the first? For this reason, and for no other, viz. that, when we come to inspect the watch, we perceive (what we could not discover in the stone) that its several parts are framed and put together for a purpose, e.g. that they are so formed and adjusted as to produce motion, and that motion so regulated as to point out the hour of the day; that, if the several parts had been differently shaped from what they are, of a different size from what they are, or placed after any other manner, or in any other order, than that in which they are placed, either no motion at all would have been carried on in the machine, or none which would have answered the use, that is now served by it.

My comment: Without knowing about biology as we do today, Paley made an observation, which is spot on, and has astounding significance and correctness, applied to the reality of the molecular world. Let's list the points he mentioned again:

- parts differently shaped

- different size

- placed after any other manner

- or in any other order

no motion would be the result.

That applies precisely as well to biological systems, and cells. Each of these four points must evolve correctly, or no improved or new biological function is granted. How many mutations would be required to get from a unicellular organism to multicellular organism? Would evolution not have to go in a gradual slow, increasing manner from one eukaryotic cell to an organism with two cells, 3 cells, and so on, to get in the end an organism with millions, and billions of cells? Let's suppose there were unicellular organisms, and evolutionary pressure to go from one to two cells. What and how many mutations would be required in the genome? Mutations would have to provide the change of a considerable number of internal cell functions and created NEW information for AT LEAST all four requirements mentioned by Paley, but many more, as listed here :

https://reasonandscience.catsboard.com/t2010-unicellular-and-multicellular-organisms-are-best-explained-through-design#5651

He continues: To reckon up a few of the plainest of these parts, and of their offices, all tending to one result:––We see a cylindrical box containing a coiled elastic spring, which, by its endeavor to relax, turns round the box. We next observe a flexible chain (artificially wrought for the sake of flexure) communicating the action of the spring from the box to the fusee. We then find a series of wheels, the teeth of which catch in, and apply to, each other, conducting the motion from the fusee to the balance, and from the balance to the pointer; and at the same time, by the size and shape of those wheels, so regulating that motion, as to terminate in causing an index, by an equable and measured progression, to pass over a given space in a given time. We take notice that the wheels are made of brass, in order to keep them from rust; the springs of steel, no other metal being so elastic; that over the face of

the watch there is placed a glass, a material employed in no other part of the work, but, in the room of which, if there had been any other than a transparent substance, the hour could not be seen without opening the case.

My comment: The choice of materials is also an essential ingredient and factor to be considered. Bones are totally different in terms of consistency than collagen - both essential for advanced multicellular organisms, and its synthesis is highly complex, ordered, it depends on the right substrates, right intake of the cell, complex mechanisms to transform brute forms of molecules into useful form, complex molecular machines, and manufacturing processes, and the information to direct the material to the right place. A lot of things to inform and to get right, in order for natural selection to choose just the right random mutations, no?

This mechanism* being observed (it requires indeed an examination of the instrument, and perhaps some previous knowledge of the subject, to perceive and understand it; but being once, as we have said, observed and understood), the inference, we think, is inevitable; that the watch must have had a maker; that there must have existed, at some time and at some place or other, an artificer or artificers who formed it for the purpose which we find it actually to answer; who comprehended its construction, and designed its use.

My comment: Now Paley goes to address the common objections: " We have never observed a being of any capacity creating biological systems and life."

I. Nor would it, I apprehend, weaken the conclusion, that we had never seen a watch made; that we had never known an artist capable of making one; that we were altogether incapable of executing such a piece of workmanship ourselves, or of understanding in what manner it was performed: all this being no more than what is true of some exquisite remains of ancient art, of some lost arts, and, to the generality of mankind, of the more curious productions of modern manufacture. Does one man in a million know how oval frames are turned? Ignorance of this kind exalts our opinion of the unseen and unknown artist’s skill, if he be unseen and unknown, but raises no

doubt in our minds of the existence and agency of such an artist, at some former time, and in some place or other. Nor can I perceive that it varies at all the inference, whether the question arise concerning a human agent, or concerning an agent of a different species, or an agent possessing, in some respects, a different nature.

Next objection: Does bad design mean no design?

II. Neither, secondly, would it invalidate our conclusion, that the watch sometimes went wrong, or that it seldom went exactly right. The purpose of the machinery, the design, and the designer, might be evident, and in the case supposed would be evident, in whatever way we accounted for the irregularity of the movement, or whether we could account for it or not. It is not necessary that a machine be perfect, in order to shew with what design it was made: still less necessary, where the only question is, whether it were made with any design at all.

Objection: We don't know the use of a particular organ in a biological system:

III. Nor, thirdly, would it bring any uncertainty into the argument, if there were a few parts of the watch, concerning which we could not discover, or had not yet discovered, in what manner they conduced to the general effect; or even some parts, concerning which we could not ascertain, whether they conduced to that effect in any manner whatever. For, as to the first branch of the case; if, by the loss, or disorder, or decay of the parts in question, the movement of the watch were found in fact to be stopped, or disturbed, or retarded, no doubt would remain in our minds as to the utility or intention of these parts, although we should be unable to investigate the manner according to which, or the connection by which, the ultimate effect depended upon their action or assistance: and the more complex is the machine, the more likely is this obscurity to arise. Then, as to the second thing supposed, namely, that there were parts, which might be spared without prejudice to the movement of the watch, and that we had proved this by experiment,––these superfluous parts, even if we were completely assured that they were such, would not vacate the reasoning which we had instituted concerning other parts. The indication of contrivance remained, with respect to them, nearly as it was before.

Objection: Physical laws, rather than design, explain the origin of complex systems:

And not less surprised to be informed, that the watch in his hand was nothing more than the result of the laws of metallic nature. It is a perversion of language to assign any law, as the efficient, operative, cause of anything. A law presupposes an agent; for it is only the mode, according to which an agent proceeds: it implies a power; for it is the order, according to which that power acts. Without this agent, without this power, which are both distinct from itself, the law does nothing; is nothing. The expression, ‘the law of metallic nature,’ may sound strange and harsh to a philosophic ear, but itseems quite as justifiable as some others which are more familiar to him, such as ‘the law of vegetable nature’––‘the law of animal nature,’ or indeed as ‘the law of nature’ in general, when assigned as the cause of phænomena, in exclusion of agency and power; or when it is substituted into the place of these.

Paley explains these similarities and differences with the aid of mechanical metaphors:

Arkwright’s mill was invented for the spinning of cotton. We see it employed for the spinning of wool, flax, and hemp, with such modifications of the original principle, such variety in the same plan, as the texture of those different materials rendered necessary. Of the machine’s being put together with design ... we could not refuse any longer our assent to the proposition, ‘‘that intelligence ... had been employed, as well in the primitive plan as in the several changes and accommodations which it is made to undergo.’’ (1850, 143)

1. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Paley

2. Natural Theology or Evidence of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity, collected from the appearances of nature

https://philosophy.lander.edu/intro/paley.shtml

1. http://www.qcc.cuny.edu/SocialSciences/ppecorino/INTRO_TEXT/Chapter%203%20Religion/Teleological.htm

https://reasonandscience.catsboard.com/t2608-paley-s-watchmaker-argument

William Paley’s “watch” argument. Basically, this argument says that after seeing a watch, with all its intricate parts, which work together in a precise fashion to keep time, one must deduce that this piece of machinery has a creator, since it is far too complex to have simply come into being by some other means, such as evolution. The skeleton of the argument is as follows:

1.Human artifacts are products of intelligent design; they have a purpose.

2.The universe resembles these human artifacts.

3.Therefore: It is probable that the universe is a product of intelligent design, and has a purpose.

4. However, the universe is vastly more complex and gigantic than a human artifact is.

5. Therefore: There is probably a powerful and vastly intelligent designer who created the universe. 1

Hume suggests that in cases where we justifiably infer from the existence of some phenomenon that a certain kind of cause must have existed, we do so on the basis of an observed pattern of correlations:

Objection: The great sceptic David Hume disposed of this sort of wishful analogical thinking nearly 250 years ago. Anyone trotting out this argument would do well to read him first before pole vaulting to untenable conclusions.

Response: Hume proposed that the universe "reproduced". His unstated assumption was that the universe did always exist ( which was the predominant view in his time) and produces "worlds" through some kind of seeding process. In fact, we know that the universe began to exist and started with the Big Bang. David Hume objected to the analogy that the universe looked like a watch, since he assumed that there was no evidence for design. However, this assumption was also based upon ignorance. Hume did not know that the universe is a finely crafted masterpiece, and that even minor changes to the laws of physics would result in a universe that didn't even contain matter! So, Hume's main argument turns out to be completely wrong.

Here is Hume's "cosmology":

In like manner as a tree sheds its seeds into the neighbouring fields, and produces other trees; so the great vegetable, the world, or this planetary system, produces within itself certain seeds, which, being scattered into the surrounding chaos, vegetate into new worlds. A comet, for instance, is the seed of a world; and after it has been fully ripened, by passing from sun to sun, and star to star, it is at last tossed into the unformed elements which every where surround this universe, and immediately sprouts up into a new system.

William Paley (July 1743 – 25 May 1805) was an English clergyman, Christian apologist, philosopher, and utilitarian. He is best known for his natural theology exposition of the teleological argument for the existence of God in his work Natural Theology or Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity, which made use of the watchmaker analogy. 1

I love analogies, and Paleys watchmaker analogy is a classic:

In WILLIAM PALEY's book :

Natural Theology or Evidence of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity, collected from the appearances of nature 2, page 46, he writes :

In crossing a heath, suppose I pitched my foot against a stone, and were asked how the stone came to be there, I might possibly answer, that, for any thing I knew to the contrary, it had lain there for ever: nor would it perhaps be very easy to shew the absurdity of this answer. But suppose I had found a watch* upon the ground, and it should be enquired how the watch happened to be in that place, I should hardly think of the answer which I had before given, that, for any thing I knew, the watch might have always been there. Yet why should not this answer serve for the watch, as well as for the stone? Why is it not as admissible in the second case, as in the first? For this reason, and for no other, viz. that, when we come to inspect the watch, we perceive (what we could not discover in the stone) that its several parts are framed and put together for a purpose, e.g. that they are so formed and adjusted as to produce motion, and that motion so regulated as to point out the hour of the day; that, if the several parts had been differently shaped from what they are, of a different size from what they are, or placed after any other manner, or in any other order, than that in which they are placed, either no motion at all would have been carried on in the machine, or none which would have answered the use, that is now served by it.

My comment: Without knowing about biology as we do today, Paley made an observation, which is spot on, and has astounding significance and correctness, applied to the reality of the molecular world. Let's list the points he mentioned again:

- parts differently shaped

- different size

- placed after any other manner

- or in any other order

no motion would be the result.

That applies precisely as well to biological systems, and cells. Each of these four points must evolve correctly, or no improved or new biological function is granted. How many mutations would be required to get from a unicellular organism to multicellular organism? Would evolution not have to go in a gradual slow, increasing manner from one eukaryotic cell to an organism with two cells, 3 cells, and so on, to get in the end an organism with millions, and billions of cells? Let's suppose there were unicellular organisms, and evolutionary pressure to go from one to two cells. What and how many mutations would be required in the genome? Mutations would have to provide the change of a considerable number of internal cell functions and created NEW information for AT LEAST all four requirements mentioned by Paley, but many more, as listed here :

https://reasonandscience.catsboard.com/t2010-unicellular-and-multicellular-organisms-are-best-explained-through-design#5651

He continues: To reckon up a few of the plainest of these parts, and of their offices, all tending to one result:––We see a cylindrical box containing a coiled elastic spring, which, by its endeavor to relax, turns round the box. We next observe a flexible chain (artificially wrought for the sake of flexure) communicating the action of the spring from the box to the fusee. We then find a series of wheels, the teeth of which catch in, and apply to, each other, conducting the motion from the fusee to the balance, and from the balance to the pointer; and at the same time, by the size and shape of those wheels, so regulating that motion, as to terminate in causing an index, by an equable and measured progression, to pass over a given space in a given time. We take notice that the wheels are made of brass, in order to keep them from rust; the springs of steel, no other metal being so elastic; that over the face of

the watch there is placed a glass, a material employed in no other part of the work, but, in the room of which, if there had been any other than a transparent substance, the hour could not be seen without opening the case.

My comment: The choice of materials is also an essential ingredient and factor to be considered. Bones are totally different in terms of consistency than collagen - both essential for advanced multicellular organisms, and its synthesis is highly complex, ordered, it depends on the right substrates, right intake of the cell, complex mechanisms to transform brute forms of molecules into useful form, complex molecular machines, and manufacturing processes, and the information to direct the material to the right place. A lot of things to inform and to get right, in order for natural selection to choose just the right random mutations, no?

This mechanism* being observed (it requires indeed an examination of the instrument, and perhaps some previous knowledge of the subject, to perceive and understand it; but being once, as we have said, observed and understood), the inference, we think, is inevitable; that the watch must have had a maker; that there must have existed, at some time and at some place or other, an artificer or artificers who formed it for the purpose which we find it actually to answer; who comprehended its construction, and designed its use.

My comment: Now Paley goes to address the common objections: " We have never observed a being of any capacity creating biological systems and life."

I. Nor would it, I apprehend, weaken the conclusion, that we had never seen a watch made; that we had never known an artist capable of making one; that we were altogether incapable of executing such a piece of workmanship ourselves, or of understanding in what manner it was performed: all this being no more than what is true of some exquisite remains of ancient art, of some lost arts, and, to the generality of mankind, of the more curious productions of modern manufacture. Does one man in a million know how oval frames are turned? Ignorance of this kind exalts our opinion of the unseen and unknown artist’s skill, if he be unseen and unknown, but raises no

doubt in our minds of the existence and agency of such an artist, at some former time, and in some place or other. Nor can I perceive that it varies at all the inference, whether the question arise concerning a human agent, or concerning an agent of a different species, or an agent possessing, in some respects, a different nature.

Next objection: Does bad design mean no design?

II. Neither, secondly, would it invalidate our conclusion, that the watch sometimes went wrong, or that it seldom went exactly right. The purpose of the machinery, the design, and the designer, might be evident, and in the case supposed would be evident, in whatever way we accounted for the irregularity of the movement, or whether we could account for it or not. It is not necessary that a machine be perfect, in order to shew with what design it was made: still less necessary, where the only question is, whether it were made with any design at all.

Objection: We don't know the use of a particular organ in a biological system:

III. Nor, thirdly, would it bring any uncertainty into the argument, if there were a few parts of the watch, concerning which we could not discover, or had not yet discovered, in what manner they conduced to the general effect; or even some parts, concerning which we could not ascertain, whether they conduced to that effect in any manner whatever. For, as to the first branch of the case; if, by the loss, or disorder, or decay of the parts in question, the movement of the watch were found in fact to be stopped, or disturbed, or retarded, no doubt would remain in our minds as to the utility or intention of these parts, although we should be unable to investigate the manner according to which, or the connection by which, the ultimate effect depended upon their action or assistance: and the more complex is the machine, the more likely is this obscurity to arise. Then, as to the second thing supposed, namely, that there were parts, which might be spared without prejudice to the movement of the watch, and that we had proved this by experiment,––these superfluous parts, even if we were completely assured that they were such, would not vacate the reasoning which we had instituted concerning other parts. The indication of contrivance remained, with respect to them, nearly as it was before.

Objection: Physical laws, rather than design, explain the origin of complex systems:

And not less surprised to be informed, that the watch in his hand was nothing more than the result of the laws of metallic nature. It is a perversion of language to assign any law, as the efficient, operative, cause of anything. A law presupposes an agent; for it is only the mode, according to which an agent proceeds: it implies a power; for it is the order, according to which that power acts. Without this agent, without this power, which are both distinct from itself, the law does nothing; is nothing. The expression, ‘the law of metallic nature,’ may sound strange and harsh to a philosophic ear, but itseems quite as justifiable as some others which are more familiar to him, such as ‘the law of vegetable nature’––‘the law of animal nature,’ or indeed as ‘the law of nature’ in general, when assigned as the cause of phænomena, in exclusion of agency and power; or when it is substituted into the place of these.

Paley explains these similarities and differences with the aid of mechanical metaphors:

Arkwright’s mill was invented for the spinning of cotton. We see it employed for the spinning of wool, flax, and hemp, with such modifications of the original principle, such variety in the same plan, as the texture of those different materials rendered necessary. Of the machine’s being put together with design ... we could not refuse any longer our assent to the proposition, ‘‘that intelligence ... had been employed, as well in the primitive plan as in the several changes and accommodations which it is made to undergo.’’ (1850, 143)

1. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Paley

2. Natural Theology or Evidence of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity, collected from the appearances of nature

https://philosophy.lander.edu/intro/paley.shtml

1. http://www.qcc.cuny.edu/SocialSciences/ppecorino/INTRO_TEXT/Chapter%203%20Religion/Teleological.htm

Last edited by Otangelo on Mon Jan 02, 2023 3:10 pm; edited 8 times in total