Fine-tuning of the Higgs-mass: It will knock your socks off.

https://reasonandscience.catsboard.com/t3142-fine-tuning-of-the-higgs-mass-it-will-knock-your-socks-off

Leonard Susskind The Cosmic Landscape: String Theory and the Illusion of Intelligent Design 2006, page 99

If it were as easy to “switch on” the Higgs field as it is to switch on the magnetic field, we could change the mass of the electron at will. Increasing the mass would cause the atomic electrons to be pulled closer to the nucleus and would dramatically change chemistry. The masses of quarks that comprise the proton and neutron would increase and modify the properties of nuclei, at some point destroying them entirely. Even more disruptive, shifting the Higgs field in the other direction would eliminate the mass ofthe electron altogether. The electron would become so light that it couldn’t be contained within the atom. Again, this is not something we would want to do where we live. The changes would have disastrous effects and render the world uninhabitable. Most significant changes in the Laws of Physics would be fatal

https://3lib.net/book/2472017/1d5be1

The Higgs Force: A force which role is dramatic: it allows all the elementary particles described in the table above to get a mass.

A Creator is a serious epistemic possibility. If our world is a massive peer-to-peer networked computer simulation, it probably had to be made. Peer-to-peer networking--particularly networking on this massive of a level--is incredibly complex and requires an incredible amount of processing power. The more someone understands physics and cosmology, the more miraculous this entire world seems to be. The following example of fine-tuning will knock your socks off. You may (or may not) have heard of the Standard Model of particle physics. While the Standard Model is widely thought to be incomplete, it is an exquisitely well-verified model. It makes crazy-precise predictions about what we should observe in particle colliders, and each of the particles it predicts has been observed. Indeed, the final "key to the puzzle"--the only particle the model predicted but had never been observed, the Higgs Boson--was finally observed (decades after its first prediction) just over two years ago. 2

The Higgs Boson is a unique particle unlike any other: it is the particle that all other known particles interact with that gives them mass. Without the Higgs, there would be nothing with mass at all! But, here's the really crazy thing. Although the Standard Model did not predict the Higgs' mass, its mass was found to be in literally the most improbable place you could expect to find it.

As you can see, the Higgs mass was found in a little sliver of the chart labeled "meta-stability." Let me explain what this means. Very roughly, an unstable or non-perturbative universe (red areas) are sort of what they sound like: they are universes that can't possibly work. A stable universe, on the other hand (green area), are universes that work all the time. Finally, there's "metastability" (yellow area), which means that the universe works sometimes but not always. In the metastable area, the Higgs is temporarily set at one value--the value that makes our universe go round--but will someday fall to a different value: yes, that's right, a value with all new physics (since the Higgs will then interact with all other particles in a different way). Not only are we in the yellow area (a place where it is very hard for the Higgs to 'stay'). We are in almost the littlest sliver of the yellow area: which means that our Higgs will be stable for a super-duper long time, but not always. Someday, the Higgs will change, and our universe will become another--one where, in an instant, none of us, none of our planets, stars, etc. exist. One in which all of physics changes. All in an instant. This is where we found the Higgs boson to be. We found it in the littlest, most unlikely sliver of the most unlikely area to find it.

Is a metastable universe is more confirmatory of a creator rather than a stable universe?

Maybe there is not a good answer. The basic idea is that the more improbable the world is--the more we find the world's parameters *could* have been one way, but instead occupy the most improbable values across a range of phenomena--the more reason we have to think that something fishy is going on. If you found one pile of rocks on a path in the shape of an arrow, you might reasonably chalk it up to happenstance. If you found two sets of rocks miles apart pointing in the same direction, you still might do so. If you found not only rocks shaped like arrows, but also arrows carved into trees, and so on, you would probably get suspicious that something fishy is going on. It *could* all just be chance, but all the same, the *chance* that it is just chance seems progressively smaller the more improbable coincidences one finds.

This is especially true if you think, as I do, that quantum mechanics *itself* is plausibly evidence that we live in a peer-to-peer simulation. But of course this is just my own position.

In any case, to address your positive suggestion, "it seems to me that a creator would prefer a stable universe, but I may be missing something"--there are a number of (admittedly speculative) reasons why a creator might have made a metastable universe. One reason might be to leave "breadcrumbs" to us that the world was created (along the lines of my suggestion above, that the more coincidences one finds--along with perhaps the best explanation of quantum mechanics being that we are in a simulation--the more probabilistic evidence we might have of creation). Another possible reason for creating a metastable universe might be to create different epochs. It is, after all, a fundamental part of most major religions that the world will be one way (Fallen/Imperfect) for a very long time, but then someday fundamentally change to a more perfect state. It could be that metastability is a burning wick of sorts to fundamentally alter the constitution and function of the universe--but of course, this is pure speculation (as is all this stuff, admittedly:).

Hugh Ross: Why the universe is the way it is, page 146

Revelation describes the new creation that will one day replace the universe as a place without decay, death, or cause for grief or frustration (see Rev. 21:4). The descriptive details imply that neither gravity nor electromagnetism will exist there. The physics and dimensionality of the new creation will be radically different from the laws and dimensions governing the present universe. With evil forever gone, God will replace the universe with a realm that includes unlimited relationships, intimacy, love, pleasure, and fulfillment

There is another way to put all of this. Imagine a very steep cliff with almost no jagged edges. If you were to roll a golf ball toward the edge of this cliff, where would you expect it to end up? Answer: one of two places: either someplace before the edge (i.e. on land before the cliff) or at the very bottom. The chances of the ball somehow stopping on just a tiny jagged edge would the most improbable thing you could imagine--sort of like the very well-known and justly famous cliff-climbing mountain goats:

The observed Higgs value tells us that our universe is like these goats. Or, to use another helpful image, consider an empty coffee cup. If you were to drop an individual coffee droplet out of the sky, where would you expect to find it? Answer: either in the coffee cup, or outside of it. You most certainly not expect to find it perfectly balanced on the lip of the coffee cup for 13.8 billion years, without ever rolling off one side or the other. But this, again, is what our Higgs--our universe--is like.

If you roll enough golf balls off a steep ledge, sooner or later one will fall (and stay) on a little outcropping (like mountain goats). That wouldn't be very shocking. But our universe is a bit more like *every* golf ball rolled off a steep ledge perching on the most precarious position possible, with *none* of them at the bottom of a cliff.

Even IF our universe would be one amongst an infinite number of potential multiverses, ours appears to be something like the least likely universe of all in the plurality of possible universes.

20 years ago the Higgs mass could have been pretty much anything, but there was one value that was singled out as special: m_H = 125-126 GeV is the boundary of the stability region. Isn't rather remarkable that it has this special value? How to explain it?

We know that the Lord is subtle but not malicious, but it seems to me that the message that He is now sending is very clear and not the slightest subtle: there is no new Physics beyond the Standard Model (BSM) and the SM is balancing at the brink of instability. Perhaps better to seek to understand this message instead of looking for another class of excuses to ignore it. This could be a string of astonishing coincidences. But, for all that, they are absolutely astonishing.

This universe evidently ended up in the most improbable of all possible universes. Why?

One 'instance' of fine-tuning (e.g. carbon fine-tuning) would be remarkable. But dozens of different, independent instances? This is like picking up one coin, flipping it a gazillion times, it landing 'heads' every single time; then picking up a six sided die, flipping it a gazillion times, it landing on '1' every single time; then picking up a twelve-sided die, flipping it a gazillion times, it landing on '11' *every* single time; and so on.

When physicists saw the Higgs boson for the first time in 2012, they observed its mass to be very small: 125 billion electronvolts, or 125 GeV. The measurement became a prime example of an issue that dogs particle physicists and astrophysicists today: the problem of fine-tuning versus naturalness. 1

To understand what’s fishy about the observable Higgs mass being so low, first you must know that it is actually the sum of two inputs: the bare Higgs mass (which we don’t know) plus contributions from all the other Standard Model particles, contributions collectively known as “quantum corrections.”

The second number in the equation is an enormous negative, coming in around minus 10^18 GeV. Compared to that, the result of the equation, 125 GeV, is extremely small, close to zero. That means the first number, the bare Higgs mass, must be almost the opposite, to so nearly cancel it out. To some physicists, this is an unacceptably strange coincidence.

Observable parameters that don’t seem to naturally emerge from a theory, but instead must be deliberately manipulated to fit, are called “finely tuned.”

My comment: Of course, that rises the question: Fine-tuned by whom ? Deliberation is a process of thoughtfully weighing options. Deliberation emphasizes the use of logic and reason. Decisions are generally made after deliberation which requires a mind.

“In general, what we want from our theories — and in some way, our universe — is that nothing seems too contrived.”

My comment: In other words, science pressuposes naturalness, that is, natural mechanisms. Contrived means deliberately created rather than arising naturally or spontaneously.

created or arranged in a way that seems artificial.

In a theory, “when you end up with numbers that are very different in size, one can adopt the point of view that this is just a representation of how nature works and there is no special meaning in the size of the numbers.

My comment: Of course, one can do that, but on what grounds ? If there are set up quantities, constants, numbers, or sizes, which are life-permitting, rather than not, and these numbers could be different and life-prohibiting, then this should be evidence that something special is going on. Something, that is rather unnatural or designed by a mind for specific purposes.

The Higgs mass requires fine-tuning on the order of 1-in-10^34.. Like all fine-tune constants, that demands an explanation. Not all physicists see situations that are described as fine-tuning as a problem. For them, there doesn’t need to be a reason that, say, two parameters have nearly equal, opposite values that result in cancellation. After all, coincidences happen.

My comment: True, but why is it a rational inference, resorting to coincidence, luck, or chance, when the odds or likelihood to get that particular, life-permitting outcome, are astronomically small?

Giuseppe Degrassi: Higgs mass and vacuum stability in the Standard Model at NNLO 30 Sep 2013 3

The indication for a Higgs mass in the range 125–126 GeV is the most important result from the LHC so far. If no new physics at the TeV scale is discovered, it will remain as one of the few and precious handles for us to understand the governing principles of nature. The apparent near criticality of the Higgs parameters may then contain information about physics at the deepest level. We do not know if this peculiar quasi-criticality of the Higgs parameters is just a capricious numerical coincidence or the herald of some hidden truth.

Luke A. Barnes:A Fortunate Universe September 21, 2016

The trouble with Higgs

The Higgs boson gives mass to fundamental particles. The discovery of the Higgs particle, while an immense success for particle physics, brings its own fine-tuning headaches. The problem is not with what has been discovered in particle accelerators, namely the Large Hadron Collider, but with what hasn’t been seen! We’ve already been introduced to the Standard Model of particle physics, describing the building blocks of matter and radiation in the Universe. The mathematical language in which the Standard Model is written goes by the scientific name of quantum field theory.

In the 1960s and ʼ70s, Particle physicists were exploring ideas that they hoped would unify the forces of physics, showing that electromagnetism and the weak nuclear force – of which we will learn more in the next chapter – are in fact different manifestations of one fundamental force. The equations, however, had a few undesirable consequences. A new particle – massless, spinless, and electrically charged – seemed to be required, but is not observed. In fact, several of the key features of particle physics, namely the gauge bosons, would have to be massless. These problems were solved by what is known as the Higgs mechanism, after the English physicist Peter Higgs. As usual, the discovery was not made in a vacuum; a number of physicists provided clues to and glimpses of the final solution. Higgs himself refers to the ‘ABEGHHK’tH mechanism’, after the physicists Anderson, Brout, Englert, Guralnik, Hagen, Higgs, Kibble and ’t Hooft.

Part of this solution is the postulation of a new field. Fields are central to modern physics. By definition, they attach some physical quantity (or set of quantities) to every point in space and time. You can think of the temperature in a room as an example of a scalar field, a field in which every point is associated with an individual value. More complicated vector fields describe magnetic and electric fields, attaching a value and direction to every point in space and time. Yet more complex physical phenomena are described by more complex forms of fields. The particles of the Standard Model of particle physics get their mass by interacting with the Higgs field. In particular, fundamental particles get their inertial mass from the Higgs field. Think of an elephant on roller-skates: inertia is what makes it hard to push when it is stopped, and hard to stop when it is moving. You can think of the Higgs field as filling space with syrup. Particles that interact with the field are slowed down, thus behaving as if they have mass. Note that the Higgs mechanism gives mass to the fundamental particles only. In composite particles, such as protons and neutrons, the individual quark masses make up only a tiny fraction of the mass. The remainder is in the form of the energy that binds the quarks together. So, the Higgs field is responsible for the mass of fundamental particles. Moreover, the field itself can vibrate, and these waves behave like particles. The particle in question is the Higgs boson, whose discovery was one of the key scientific achievements in recent years. The Higgs boson is about 133 times heavier than a proton, with a mass of ~125 GeV (again, in particle physics units) making it a quite massive member of the particle family.

Success all around, with scientists dancing in the street! Not so fast! Here’s where the fine-tuning headache begins. In our quantum mechanical view of the Universe, empty space is not truly empty, but seethes with quantum fluctuations, with particles popping in and out of existence. Yes, it sounds like something dreamt up in an opium haze, but we need to include this fluctuation of energy on small scales to accurately account for our observations of the Universe. So, when we talk about the mass of a particle, there are two contributions. Firstly, there is the intrinsic or bare mass. Secondly, there is the constant buzzing of these quantum hangers-on. Each particle is hauling not just itself, but a cloud of vacuum fluctuations. When we measure the mass of a particle, we get both contributions. For the electron, though there are an infinite number of extra contributions, when summed up, they make only a small difference to the total mass. But for the Higgs, things are not so simple. If we play the same game and add the contributions from the vacuum, they don’t get smaller, and when you add them all up, the mass of the Higgs boson we should measure would be infinite. Clearly, something is wrong. When faced with such divergences to infinity, physicists look for a place where we can stop adding all of these contributions. There is a hard upper limit, the Planck energy. We don’t have a quantum theory of gravity, so extrapolating past the Planck energy (or equivalently, Planck mass) is pointless. Adding this cut-off drastically reduces the expected mass of the Higgs boson from infinity down to about 10^18 GeV! Getting closer, but still a long, long way from the observed value. Since the masses of the fundamental particles of the Standard Model are tied to the Higgs field, if the Higgs mass were approximately equal to the Planck mass, then all of the Standard Model particles would be similarly Planck–proportioned. And, as we have seen, increasing the fundamental particle masses by even a factor of a few is a disaster for life; increasing by 10^16 would be ... well, don’t look. It’s not pretty. So, we suspect that we’re missing something, a physical effect that wipes out the additional mass added from quantum fluctuations, and does so very precisely. Wiping out a factor of 2 is not going to save the day, as the predicted Higgs mass would still be immensely larger than is measured. A factor of a hundred or a thousand does not help. Nor a billion, nor a trillion. No, we need to balance the contributions from the vacuum by a factor of about 10^16

https://3lib.net/book/3335826/1b6fa8

Sabine Hossenfelder: Sorry, 'Flash' Fans - There's No Evidence For A Multiverse Yet Oct 25, 2016,

Theoretical physicists are not satisfied with the currently best laws of nature they have: the standard model of particle physics plus general relativity. They want to do better. The standard model contains many parameters for which there is no deeper explanation, and scientists are hoping that there exists an underlying – more fundamental – theory from which the parameters can be calculated.

A parameter that irks theoretical physicists particularly is the mass of the recently discovered Higgs-boson. It comes out to be about 125 GeV. That value is somewhat more than 100 times the mass of a proton and, on its own, sounds pretty unremarkable. But the Higgs-boson is a special particle in that it’s the only known (fundamental) scalar, which means it has spin zero. As a consequence of this, the mass of the Higgs-boson acquires correction terms from quantum fluctuations, and these correction terms are very large – larger than the observed value by almost 15 orders of magnitude.

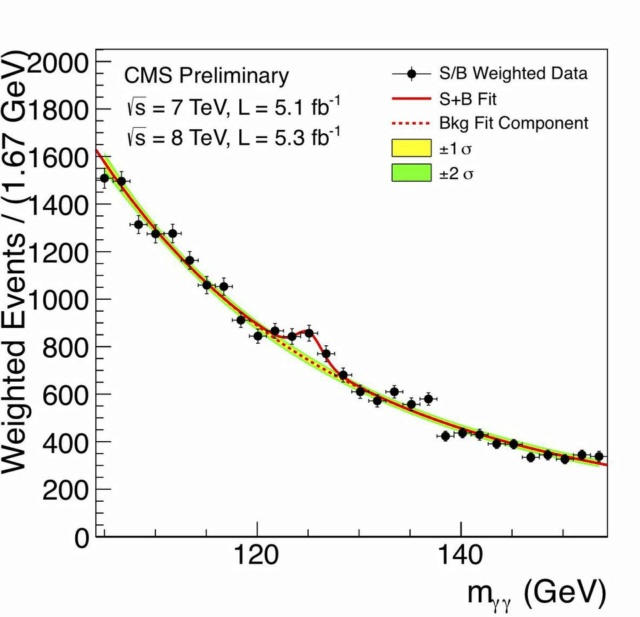

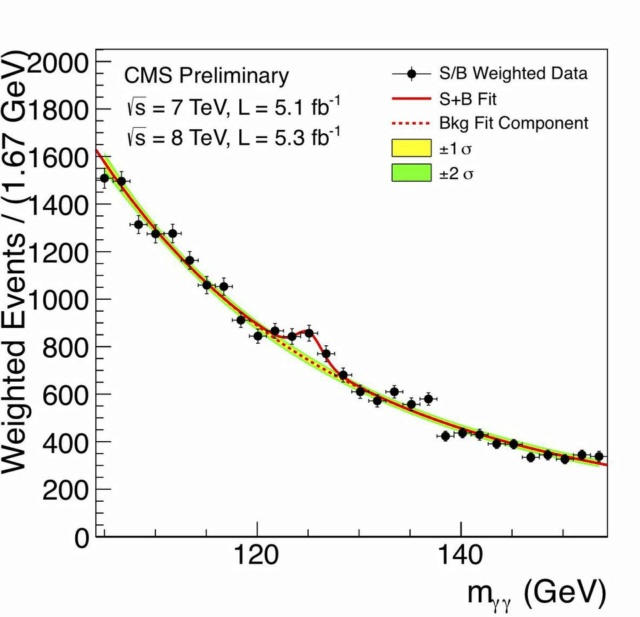

The discovery of the Higgs Boson in the di-photon (γγ) channel at CMS.

These large quantum-corrections to the Higgs-boson’s mass can be removed by subtracting a new term which is almost (but not exactly) equally large, so that the difference leaves behind the, comparably tiny, observed mass. This is possible because the observed mass is a parameter which has to be determined experimentally anyway. However, such a delicate cancellation requires finetuning: You need two constants that are equal for the first 15 digits and then differ in the 16th. If you’d pick two random numbers this would be extremely unlikely. It seems hand-selected and hence in need of explanation.

For this reason, physicists say that the small mass of the Higgs-boson is “not natural.”

The Higgs mass is the only parameter in the standard model which is not natural. Physicists understood this long before the Higgs itself was discovered, and for this reason many of them believed that the Large Hadron Collider LHC would also find evidence for new physics besides the Higgs. The new physics, so they thought, was necessary to explain the smallness of the Higgs mass and thereby make it natural.

The Standard Model particles and their supersymmetric counterparts. Exactly 50% of these particles have been discovered, and 50% have never shown a trace that they exist.

The best studied hypothesis to make the Higgs-mass natural is supersymmetry. In supersymmetric theories, every known particle comes with a partner-particle. One consequence of this doubling is that the troublesome quantum-contributions to the Higgs-mass cancel. The new symmetry enforces a cancellation, since there now must be equally large contributions to these quantum corrections with either sign: one from the normal particles and one from the supersymmetric ones.

At least, that would be so if supersymmetry were an exact symmetry of nature. We already know, however, that this can’t be the case, because then we should have seen superpartners of the standard model particles long ago. So, theoretical physicists concluded, supersymmetry must be broken, and it’s only restored above some energy scale, the “SUSY breaking scale.” The SUSY breaking scale should be in the range of the LHC, because this would make the Higgs-mass natural. If the SUSY breaking scale were much higher than that, the need to delicately cancel quantum contributions by fine-tuning would come back. The way things went, however, the LHC found the Higgs but no evidence for anything new besides that. No supersymmetry, no extra-dimensions, no black holes, no fourth generation, nothing. This means that the Higgs-mass just sits there, boldly unnatural. Since theoretical physicists haven’t found an explanation for the smallness of the Higgs-mass, they now try to accept that there simply may be no explanation.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/startswithabang/2016/10/25/no-the-lhc-hasnt-shown-that-we-live-in-a-multiverse/?sh=730014c441aa

My comment: Since theoretical physicists can’t explain the mass of the Higgs, any parameter can take on any possible value, and there might be a multiverse generator, and ours is the one that was generated by chance having the right parameters, permitting the Higgs particle.

Max Tegmark et al.: Dimensionless constants, cosmology, and other dark matters 2006

The origin of the dimensionless numbers

So why do we observe these 31 parameters to have the particular values listed in Table I? Interest in that question has grown with the gradual realization that some of these parameters appear fine-tuned for life, in the sense that small relative changes to their values would result in dramatic qualitative changes that could preclude intelligent life, and hence the very possibility of reflective observation. There are four common responses to this realization:

(1) Fluke—Any apparent fine-tuning is a fluke and is best ignored

(2) Multiverse—These parameters vary across an ensemble of physically realized and (for all practical purposes) parallel universes, and we find ourselves in one where life is possible.

(3) Design—Our universe is somehow created or simulated with parameters chosen to allow life.

(4) Fecundity—There is no fine-tuning because intelligent life of some form will emerge under extremely varied circumstances.

Options 1, 2, and 4 tend to be preferred by physicists, with recent developments in inflation and high-energy theory giving new popularity to option 2.

My comment: This is an interesting confession. Pointing to option 2, a multiverse, is based simply on personal preference, but not on evidence.

https://sci-hub.ren/10.1103/physrevd.73.023505

A multiverse is an interesting argument but it’s logically inconsistent. It relies on an expectation about what we mean by a “random number” or its probability distribution, respectively. There are infinitely many such distributions. The requirement that the numbers in the standard model should obey a certain distribution is merely a hypothesis that turned out to be incompatible with observation. That, really, is all we can conclude from the data: physicists had a hypothesis for what is “natural.” It turned out to be wrong.

My comment: Science understands how the Higgs gets its mass, but not why. Well, i for sure know why. God made it so to permit a universe filled with atmos, molecules, cells, and life.

1. https://www.symmetrymagazine.org/article/fine-tuning-versus-naturalness

2. https://philosopherscocoon.typepad.com/blog/2015/05/vacuum-stability-and-fine-tuning.html

3. https://arxiv.org/abs/1205.6497

https://reasonandscience.catsboard.com/t3142-fine-tuning-of-the-higgs-mass-it-will-knock-your-socks-off

Leonard Susskind The Cosmic Landscape: String Theory and the Illusion of Intelligent Design 2006, page 99

If it were as easy to “switch on” the Higgs field as it is to switch on the magnetic field, we could change the mass of the electron at will. Increasing the mass would cause the atomic electrons to be pulled closer to the nucleus and would dramatically change chemistry. The masses of quarks that comprise the proton and neutron would increase and modify the properties of nuclei, at some point destroying them entirely. Even more disruptive, shifting the Higgs field in the other direction would eliminate the mass ofthe electron altogether. The electron would become so light that it couldn’t be contained within the atom. Again, this is not something we would want to do where we live. The changes would have disastrous effects and render the world uninhabitable. Most significant changes in the Laws of Physics would be fatal

https://3lib.net/book/2472017/1d5be1

The Higgs Force: A force which role is dramatic: it allows all the elementary particles described in the table above to get a mass.

A Creator is a serious epistemic possibility. If our world is a massive peer-to-peer networked computer simulation, it probably had to be made. Peer-to-peer networking--particularly networking on this massive of a level--is incredibly complex and requires an incredible amount of processing power. The more someone understands physics and cosmology, the more miraculous this entire world seems to be. The following example of fine-tuning will knock your socks off. You may (or may not) have heard of the Standard Model of particle physics. While the Standard Model is widely thought to be incomplete, it is an exquisitely well-verified model. It makes crazy-precise predictions about what we should observe in particle colliders, and each of the particles it predicts has been observed. Indeed, the final "key to the puzzle"--the only particle the model predicted but had never been observed, the Higgs Boson--was finally observed (decades after its first prediction) just over two years ago. 2

The Higgs Boson is a unique particle unlike any other: it is the particle that all other known particles interact with that gives them mass. Without the Higgs, there would be nothing with mass at all! But, here's the really crazy thing. Although the Standard Model did not predict the Higgs' mass, its mass was found to be in literally the most improbable place you could expect to find it.

As you can see, the Higgs mass was found in a little sliver of the chart labeled "meta-stability." Let me explain what this means. Very roughly, an unstable or non-perturbative universe (red areas) are sort of what they sound like: they are universes that can't possibly work. A stable universe, on the other hand (green area), are universes that work all the time. Finally, there's "metastability" (yellow area), which means that the universe works sometimes but not always. In the metastable area, the Higgs is temporarily set at one value--the value that makes our universe go round--but will someday fall to a different value: yes, that's right, a value with all new physics (since the Higgs will then interact with all other particles in a different way). Not only are we in the yellow area (a place where it is very hard for the Higgs to 'stay'). We are in almost the littlest sliver of the yellow area: which means that our Higgs will be stable for a super-duper long time, but not always. Someday, the Higgs will change, and our universe will become another--one where, in an instant, none of us, none of our planets, stars, etc. exist. One in which all of physics changes. All in an instant. This is where we found the Higgs boson to be. We found it in the littlest, most unlikely sliver of the most unlikely area to find it.

Is a metastable universe is more confirmatory of a creator rather than a stable universe?

Maybe there is not a good answer. The basic idea is that the more improbable the world is--the more we find the world's parameters *could* have been one way, but instead occupy the most improbable values across a range of phenomena--the more reason we have to think that something fishy is going on. If you found one pile of rocks on a path in the shape of an arrow, you might reasonably chalk it up to happenstance. If you found two sets of rocks miles apart pointing in the same direction, you still might do so. If you found not only rocks shaped like arrows, but also arrows carved into trees, and so on, you would probably get suspicious that something fishy is going on. It *could* all just be chance, but all the same, the *chance* that it is just chance seems progressively smaller the more improbable coincidences one finds.

This is especially true if you think, as I do, that quantum mechanics *itself* is plausibly evidence that we live in a peer-to-peer simulation. But of course this is just my own position.

In any case, to address your positive suggestion, "it seems to me that a creator would prefer a stable universe, but I may be missing something"--there are a number of (admittedly speculative) reasons why a creator might have made a metastable universe. One reason might be to leave "breadcrumbs" to us that the world was created (along the lines of my suggestion above, that the more coincidences one finds--along with perhaps the best explanation of quantum mechanics being that we are in a simulation--the more probabilistic evidence we might have of creation). Another possible reason for creating a metastable universe might be to create different epochs. It is, after all, a fundamental part of most major religions that the world will be one way (Fallen/Imperfect) for a very long time, but then someday fundamentally change to a more perfect state. It could be that metastability is a burning wick of sorts to fundamentally alter the constitution and function of the universe--but of course, this is pure speculation (as is all this stuff, admittedly:).

Hugh Ross: Why the universe is the way it is, page 146

Revelation describes the new creation that will one day replace the universe as a place without decay, death, or cause for grief or frustration (see Rev. 21:4). The descriptive details imply that neither gravity nor electromagnetism will exist there. The physics and dimensionality of the new creation will be radically different from the laws and dimensions governing the present universe. With evil forever gone, God will replace the universe with a realm that includes unlimited relationships, intimacy, love, pleasure, and fulfillment

There is another way to put all of this. Imagine a very steep cliff with almost no jagged edges. If you were to roll a golf ball toward the edge of this cliff, where would you expect it to end up? Answer: one of two places: either someplace before the edge (i.e. on land before the cliff) or at the very bottom. The chances of the ball somehow stopping on just a tiny jagged edge would the most improbable thing you could imagine--sort of like the very well-known and justly famous cliff-climbing mountain goats:

The observed Higgs value tells us that our universe is like these goats. Or, to use another helpful image, consider an empty coffee cup. If you were to drop an individual coffee droplet out of the sky, where would you expect to find it? Answer: either in the coffee cup, or outside of it. You most certainly not expect to find it perfectly balanced on the lip of the coffee cup for 13.8 billion years, without ever rolling off one side or the other. But this, again, is what our Higgs--our universe--is like.

If you roll enough golf balls off a steep ledge, sooner or later one will fall (and stay) on a little outcropping (like mountain goats). That wouldn't be very shocking. But our universe is a bit more like *every* golf ball rolled off a steep ledge perching on the most precarious position possible, with *none* of them at the bottom of a cliff.

Even IF our universe would be one amongst an infinite number of potential multiverses, ours appears to be something like the least likely universe of all in the plurality of possible universes.

20 years ago the Higgs mass could have been pretty much anything, but there was one value that was singled out as special: m_H = 125-126 GeV is the boundary of the stability region. Isn't rather remarkable that it has this special value? How to explain it?

We know that the Lord is subtle but not malicious, but it seems to me that the message that He is now sending is very clear and not the slightest subtle: there is no new Physics beyond the Standard Model (BSM) and the SM is balancing at the brink of instability. Perhaps better to seek to understand this message instead of looking for another class of excuses to ignore it. This could be a string of astonishing coincidences. But, for all that, they are absolutely astonishing.

This universe evidently ended up in the most improbable of all possible universes. Why?

One 'instance' of fine-tuning (e.g. carbon fine-tuning) would be remarkable. But dozens of different, independent instances? This is like picking up one coin, flipping it a gazillion times, it landing 'heads' every single time; then picking up a six sided die, flipping it a gazillion times, it landing on '1' every single time; then picking up a twelve-sided die, flipping it a gazillion times, it landing on '11' *every* single time; and so on.

When physicists saw the Higgs boson for the first time in 2012, they observed its mass to be very small: 125 billion electronvolts, or 125 GeV. The measurement became a prime example of an issue that dogs particle physicists and astrophysicists today: the problem of fine-tuning versus naturalness. 1

To understand what’s fishy about the observable Higgs mass being so low, first you must know that it is actually the sum of two inputs: the bare Higgs mass (which we don’t know) plus contributions from all the other Standard Model particles, contributions collectively known as “quantum corrections.”

The second number in the equation is an enormous negative, coming in around minus 10^18 GeV. Compared to that, the result of the equation, 125 GeV, is extremely small, close to zero. That means the first number, the bare Higgs mass, must be almost the opposite, to so nearly cancel it out. To some physicists, this is an unacceptably strange coincidence.

Observable parameters that don’t seem to naturally emerge from a theory, but instead must be deliberately manipulated to fit, are called “finely tuned.”

My comment: Of course, that rises the question: Fine-tuned by whom ? Deliberation is a process of thoughtfully weighing options. Deliberation emphasizes the use of logic and reason. Decisions are generally made after deliberation which requires a mind.

“In general, what we want from our theories — and in some way, our universe — is that nothing seems too contrived.”

My comment: In other words, science pressuposes naturalness, that is, natural mechanisms. Contrived means deliberately created rather than arising naturally or spontaneously.

created or arranged in a way that seems artificial.

In a theory, “when you end up with numbers that are very different in size, one can adopt the point of view that this is just a representation of how nature works and there is no special meaning in the size of the numbers.

My comment: Of course, one can do that, but on what grounds ? If there are set up quantities, constants, numbers, or sizes, which are life-permitting, rather than not, and these numbers could be different and life-prohibiting, then this should be evidence that something special is going on. Something, that is rather unnatural or designed by a mind for specific purposes.

The Higgs mass requires fine-tuning on the order of 1-in-10^34.. Like all fine-tune constants, that demands an explanation. Not all physicists see situations that are described as fine-tuning as a problem. For them, there doesn’t need to be a reason that, say, two parameters have nearly equal, opposite values that result in cancellation. After all, coincidences happen.

My comment: True, but why is it a rational inference, resorting to coincidence, luck, or chance, when the odds or likelihood to get that particular, life-permitting outcome, are astronomically small?

Giuseppe Degrassi: Higgs mass and vacuum stability in the Standard Model at NNLO 30 Sep 2013 3

The indication for a Higgs mass in the range 125–126 GeV is the most important result from the LHC so far. If no new physics at the TeV scale is discovered, it will remain as one of the few and precious handles for us to understand the governing principles of nature. The apparent near criticality of the Higgs parameters may then contain information about physics at the deepest level. We do not know if this peculiar quasi-criticality of the Higgs parameters is just a capricious numerical coincidence or the herald of some hidden truth.

Luke A. Barnes:A Fortunate Universe September 21, 2016

The trouble with Higgs

The Higgs boson gives mass to fundamental particles. The discovery of the Higgs particle, while an immense success for particle physics, brings its own fine-tuning headaches. The problem is not with what has been discovered in particle accelerators, namely the Large Hadron Collider, but with what hasn’t been seen! We’ve already been introduced to the Standard Model of particle physics, describing the building blocks of matter and radiation in the Universe. The mathematical language in which the Standard Model is written goes by the scientific name of quantum field theory.

In the 1960s and ʼ70s, Particle physicists were exploring ideas that they hoped would unify the forces of physics, showing that electromagnetism and the weak nuclear force – of which we will learn more in the next chapter – are in fact different manifestations of one fundamental force. The equations, however, had a few undesirable consequences. A new particle – massless, spinless, and electrically charged – seemed to be required, but is not observed. In fact, several of the key features of particle physics, namely the gauge bosons, would have to be massless. These problems were solved by what is known as the Higgs mechanism, after the English physicist Peter Higgs. As usual, the discovery was not made in a vacuum; a number of physicists provided clues to and glimpses of the final solution. Higgs himself refers to the ‘ABEGHHK’tH mechanism’, after the physicists Anderson, Brout, Englert, Guralnik, Hagen, Higgs, Kibble and ’t Hooft.

Part of this solution is the postulation of a new field. Fields are central to modern physics. By definition, they attach some physical quantity (or set of quantities) to every point in space and time. You can think of the temperature in a room as an example of a scalar field, a field in which every point is associated with an individual value. More complicated vector fields describe magnetic and electric fields, attaching a value and direction to every point in space and time. Yet more complex physical phenomena are described by more complex forms of fields. The particles of the Standard Model of particle physics get their mass by interacting with the Higgs field. In particular, fundamental particles get their inertial mass from the Higgs field. Think of an elephant on roller-skates: inertia is what makes it hard to push when it is stopped, and hard to stop when it is moving. You can think of the Higgs field as filling space with syrup. Particles that interact with the field are slowed down, thus behaving as if they have mass. Note that the Higgs mechanism gives mass to the fundamental particles only. In composite particles, such as protons and neutrons, the individual quark masses make up only a tiny fraction of the mass. The remainder is in the form of the energy that binds the quarks together. So, the Higgs field is responsible for the mass of fundamental particles. Moreover, the field itself can vibrate, and these waves behave like particles. The particle in question is the Higgs boson, whose discovery was one of the key scientific achievements in recent years. The Higgs boson is about 133 times heavier than a proton, with a mass of ~125 GeV (again, in particle physics units) making it a quite massive member of the particle family.

Success all around, with scientists dancing in the street! Not so fast! Here’s where the fine-tuning headache begins. In our quantum mechanical view of the Universe, empty space is not truly empty, but seethes with quantum fluctuations, with particles popping in and out of existence. Yes, it sounds like something dreamt up in an opium haze, but we need to include this fluctuation of energy on small scales to accurately account for our observations of the Universe. So, when we talk about the mass of a particle, there are two contributions. Firstly, there is the intrinsic or bare mass. Secondly, there is the constant buzzing of these quantum hangers-on. Each particle is hauling not just itself, but a cloud of vacuum fluctuations. When we measure the mass of a particle, we get both contributions. For the electron, though there are an infinite number of extra contributions, when summed up, they make only a small difference to the total mass. But for the Higgs, things are not so simple. If we play the same game and add the contributions from the vacuum, they don’t get smaller, and when you add them all up, the mass of the Higgs boson we should measure would be infinite. Clearly, something is wrong. When faced with such divergences to infinity, physicists look for a place where we can stop adding all of these contributions. There is a hard upper limit, the Planck energy. We don’t have a quantum theory of gravity, so extrapolating past the Planck energy (or equivalently, Planck mass) is pointless. Adding this cut-off drastically reduces the expected mass of the Higgs boson from infinity down to about 10^18 GeV! Getting closer, but still a long, long way from the observed value. Since the masses of the fundamental particles of the Standard Model are tied to the Higgs field, if the Higgs mass were approximately equal to the Planck mass, then all of the Standard Model particles would be similarly Planck–proportioned. And, as we have seen, increasing the fundamental particle masses by even a factor of a few is a disaster for life; increasing by 10^16 would be ... well, don’t look. It’s not pretty. So, we suspect that we’re missing something, a physical effect that wipes out the additional mass added from quantum fluctuations, and does so very precisely. Wiping out a factor of 2 is not going to save the day, as the predicted Higgs mass would still be immensely larger than is measured. A factor of a hundred or a thousand does not help. Nor a billion, nor a trillion. No, we need to balance the contributions from the vacuum by a factor of about 10^16

https://3lib.net/book/3335826/1b6fa8

Sabine Hossenfelder: Sorry, 'Flash' Fans - There's No Evidence For A Multiverse Yet Oct 25, 2016,

Theoretical physicists are not satisfied with the currently best laws of nature they have: the standard model of particle physics plus general relativity. They want to do better. The standard model contains many parameters for which there is no deeper explanation, and scientists are hoping that there exists an underlying – more fundamental – theory from which the parameters can be calculated.

A parameter that irks theoretical physicists particularly is the mass of the recently discovered Higgs-boson. It comes out to be about 125 GeV. That value is somewhat more than 100 times the mass of a proton and, on its own, sounds pretty unremarkable. But the Higgs-boson is a special particle in that it’s the only known (fundamental) scalar, which means it has spin zero. As a consequence of this, the mass of the Higgs-boson acquires correction terms from quantum fluctuations, and these correction terms are very large – larger than the observed value by almost 15 orders of magnitude.

The discovery of the Higgs Boson in the di-photon (γγ) channel at CMS.

These large quantum-corrections to the Higgs-boson’s mass can be removed by subtracting a new term which is almost (but not exactly) equally large, so that the difference leaves behind the, comparably tiny, observed mass. This is possible because the observed mass is a parameter which has to be determined experimentally anyway. However, such a delicate cancellation requires finetuning: You need two constants that are equal for the first 15 digits and then differ in the 16th. If you’d pick two random numbers this would be extremely unlikely. It seems hand-selected and hence in need of explanation.

For this reason, physicists say that the small mass of the Higgs-boson is “not natural.”

The Higgs mass is the only parameter in the standard model which is not natural. Physicists understood this long before the Higgs itself was discovered, and for this reason many of them believed that the Large Hadron Collider LHC would also find evidence for new physics besides the Higgs. The new physics, so they thought, was necessary to explain the smallness of the Higgs mass and thereby make it natural.

The Standard Model particles and their supersymmetric counterparts. Exactly 50% of these particles have been discovered, and 50% have never shown a trace that they exist.

The best studied hypothesis to make the Higgs-mass natural is supersymmetry. In supersymmetric theories, every known particle comes with a partner-particle. One consequence of this doubling is that the troublesome quantum-contributions to the Higgs-mass cancel. The new symmetry enforces a cancellation, since there now must be equally large contributions to these quantum corrections with either sign: one from the normal particles and one from the supersymmetric ones.

At least, that would be so if supersymmetry were an exact symmetry of nature. We already know, however, that this can’t be the case, because then we should have seen superpartners of the standard model particles long ago. So, theoretical physicists concluded, supersymmetry must be broken, and it’s only restored above some energy scale, the “SUSY breaking scale.” The SUSY breaking scale should be in the range of the LHC, because this would make the Higgs-mass natural. If the SUSY breaking scale were much higher than that, the need to delicately cancel quantum contributions by fine-tuning would come back. The way things went, however, the LHC found the Higgs but no evidence for anything new besides that. No supersymmetry, no extra-dimensions, no black holes, no fourth generation, nothing. This means that the Higgs-mass just sits there, boldly unnatural. Since theoretical physicists haven’t found an explanation for the smallness of the Higgs-mass, they now try to accept that there simply may be no explanation.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/startswithabang/2016/10/25/no-the-lhc-hasnt-shown-that-we-live-in-a-multiverse/?sh=730014c441aa

My comment: Since theoretical physicists can’t explain the mass of the Higgs, any parameter can take on any possible value, and there might be a multiverse generator, and ours is the one that was generated by chance having the right parameters, permitting the Higgs particle.

Max Tegmark et al.: Dimensionless constants, cosmology, and other dark matters 2006

The origin of the dimensionless numbers

So why do we observe these 31 parameters to have the particular values listed in Table I? Interest in that question has grown with the gradual realization that some of these parameters appear fine-tuned for life, in the sense that small relative changes to their values would result in dramatic qualitative changes that could preclude intelligent life, and hence the very possibility of reflective observation. There are four common responses to this realization:

(1) Fluke—Any apparent fine-tuning is a fluke and is best ignored

(2) Multiverse—These parameters vary across an ensemble of physically realized and (for all practical purposes) parallel universes, and we find ourselves in one where life is possible.

(3) Design—Our universe is somehow created or simulated with parameters chosen to allow life.

(4) Fecundity—There is no fine-tuning because intelligent life of some form will emerge under extremely varied circumstances.

Options 1, 2, and 4 tend to be preferred by physicists, with recent developments in inflation and high-energy theory giving new popularity to option 2.

My comment: This is an interesting confession. Pointing to option 2, a multiverse, is based simply on personal preference, but not on evidence.

https://sci-hub.ren/10.1103/physrevd.73.023505

A multiverse is an interesting argument but it’s logically inconsistent. It relies on an expectation about what we mean by a “random number” or its probability distribution, respectively. There are infinitely many such distributions. The requirement that the numbers in the standard model should obey a certain distribution is merely a hypothesis that turned out to be incompatible with observation. That, really, is all we can conclude from the data: physicists had a hypothesis for what is “natural.” It turned out to be wrong.

My comment: Science understands how the Higgs gets its mass, but not why. Well, i for sure know why. God made it so to permit a universe filled with atmos, molecules, cells, and life.

1. https://www.symmetrymagazine.org/article/fine-tuning-versus-naturalness

2. https://philosopherscocoon.typepad.com/blog/2015/05/vacuum-stability-and-fine-tuning.html

3. https://arxiv.org/abs/1205.6497

Last edited by Otangelo on Tue Jun 22, 2021 6:56 am; edited 1 time in total