What an incredible open admission of biased thinking. Wilczek admitted that the golden standard that physicists like him searched for, were mathematical principles that would ground and explain the fine-tuning of our universe to permit life. Or the right numbers that have to be inserted in the equations to have a life-sustaining universe, full of atoms, stars, and planets. And then he proceeds and says: There is the temptation, that we have to give up, and admit to the anthropic principle, or the fact that God is necessary to fine-tune the parameters. Why does he think that is a science stopper? Why is he hesitating to admit the obvious? Because he and his colleagues are staunched atheists, and they have done everything to exclude God. What has been a humiliation for the origin of life researchers, extends to physicists like him. It is a loss for atheists, but a win for us, that give praise to our creator.

Welcome to my library—a curated collection of research and original arguments exploring why I believe Christianity, creationism, and Intelligent Design offer the most compelling explanations for our origins. Otangelo Grasso

Fine tuning of the Universe

Go to page :  1, 2

1, 2

26 Re: Fine tuning of the Universe Thu May 19, 2022 2:46 pm

Re: Fine tuning of the Universe Thu May 19, 2022 2:46 pm

Otangelo

Admin

What an incredible open admission of biased thinking. Wilczek admitted that the golden standard that physicists like him searched for, were mathematical principles that would ground and explain the fine-tuning of our universe to permit life. Or the right numbers that have to be inserted in the equations to have a life-sustaining universe, full of atoms, stars, and planets. And then he proceeds and says: There is the temptation, that we have to give up, and admit to the anthropic principle, or the fact that God is necessary to fine-tune the parameters. Why does he think that is a science stopper? Why is he hesitating to admit the obvious? Because he and his colleagues are staunched atheists, and they have done everything to exclude God. What has been a humiliation for the origin of life researchers, extends to physicists like him. It is a loss for atheists, but a win for us, that give praise to our creator.

27 Re: Fine tuning of the Universe Tue Aug 30, 2022 12:49 pm

Re: Fine tuning of the Universe Tue Aug 30, 2022 12:49 pm

Otangelo

Admin

The teleological argument becomes more robust, the more it accumulates. One line of evidence leading to design as the best explanation is already good. 3 together is, IMHO, MUCH BETTER.

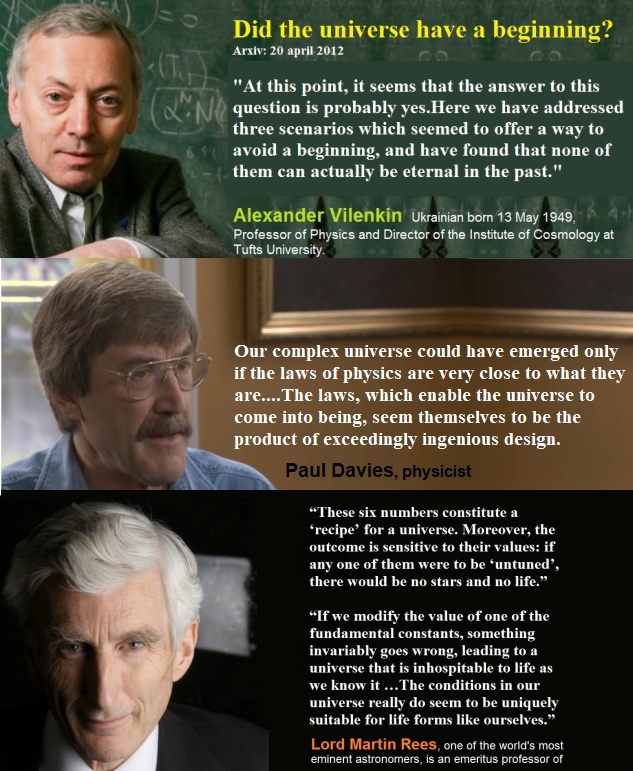

Mithani, and Vilenkin: Margenau and Varghese eds, La Salle, IL, Open Court, 1992, p. 83

Did the universe have a beginning?:

At this point, it seems that the answer to this question is probably yes. Here we have addressed three scenarios which seemed to offer a way to avoid a beginning, and have found that none of them can actually be eternal in the past.

http://arxiv.org/pdf/1204.4658v1.pdf

Astrophysicist Paul Davies declared: Our complex universe could have emerged only if the laws of physics are very close to what they are....The laws, which enable the universe to come into being, seem themselves to be the product of exceedingly ingenious design. If physics is the product of design, the universe must have a purpose, and the evidence of modern physics suggests strongly to me that the purpose includes us.

Superforce (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984), 243.

Martin Rees is an atheist and a qualified astronomer. He wrote a book called “Just Six Numbers: The Deep Forces That Shape The Universe”, (Basic Books: 2001). In it, he discusses 6 numbers that need to be fine-tuned in order to have a life-permitting universe. These six numbers constitute a ‘recipe’ for a universe. Moreover, the outcome is sensitive to their values: if any one of them were to be ‘untuned’, there would be no stars and no life. Is this tuning just a brute fact, a coincidence? Or is it the providence of a benign Creator? There are some atheists who deny the fine-tuning, but these atheists are in firm opposition to the progress of science. The more science has progressed, the more constants, ratios and quantities we have discovered that need to be fine-tuned.

The universe had a beginning

https://reasonandscience.catsboard.com/t1297-beginning-the-universe-had-a-beginning

1. The theory of the Big bang is a scientific consensus today: According to Hawking, Einstein, Rees, Vilenkin, Penzias, Jastrow, Krauss, and 100’s other physicists, finite nature (time/space/matter) had a beginning. While we cannot go back further than Planck's time, what we do know, permits us to posit a beginning.

2. The 2nd law of thermodynamics refutes the possibility of an eternal universe. Luke A. Barnes: The Second Law points to a beginning when, for the first time, the Universe was in a state where all energy was available for use; and an end in the future when no more energy will be available (referred to by scientists as a “heat death”, thus causing the Universe to “die.” In other words, the Universe is like a giant watch that has been wound up, but that now is winding down. The conclusion to be drawn from the scientific data is inescapable—the Universe is not eternal.

3. Philosophical reasons why the universe cannot be past eternal: If we start counting from now, we can count infinitely. We can always add one discrete section of time to another. If we count backwards from now, the same. But in both cases, there is a starting point. That is what we try to avoid when we talk about an infinite past without a beginning. So how can you even count without an end, forwards, or backwards, if there is no starting point? A reference point to start counting is necessary to get somewhere, or you never get "there".

Laws of Physics, fine-tuned for a life-permitting universe

https://reasonandscience.catsboard.com/t1336-laws-of-physics-fine-tuned-for-a-life-permitting-universe

1. The Laws of physics are like the computer software, driving the physical universe, which corresponds to the hardware. All the known fundamental laws of physics are expressed in terms of differentiable functions defined over the set of real or complex numbers. The properties of the physical universe depend in an obvious way on the laws of physics, but the basic laws themselves depend not one iota on what happens in the physical universe.There is thus a fundamental asymmetry: the states of the world are affected by the laws, but the laws are completely unaffected by the states. Einstein was a physicist and he believed that math is invented, not discovered. His sharpest statement on this is his declaration that “the series of integers is obviously an invention of the human mind, a self-created tool which simplifies the ordering of certain sensory experiences.” All concepts, even those closest to experience, are from the point of view of logic freely chosen posits. . .

2. The laws of physics are immutable: absolute, perfect mathematical relationships, infinitely precise in form. The laws were imprinted on the universe at the moment of creation, i.e. at the big bang, and have since remained fixed in both space and time.

3. The ultimate source of the laws transcend the universe itself, i.e. to lie beyond the physical world. The only rational inference is that the physical laws emanate from the mind of God.

https://arxiv.org/pdf/math/0302333.pdf

Fine-tuning of the universe

https://reasonandscience.catsboard.com/t1277-fine-tuning-of-the-universe

1. The existence of a life-permitting universe is very improbable on naturalism and very likely on theism.

2. A universe formed by naturalistic unguided means would have its parameters set randomly, and with high probability, there would be no universe at all. ( The fine-tune parameters for the right expansion-rate of the universe would most likely not be met ) In short, a randomly chosen universe is extraordinarily unlikely to have the right conditions for life.

3. A life-permitting universe is likely on theism, since a powerful, extraordinarily intelligent designer has the ability of foresight, and knowledge of what parameters, laws of physics, and finely-tuned conditions would permit a life-permitting universe.

4. Under bayesian terms, design is more likely rather than non-design. Therefore, the design inference is the best explanation for a finely tuned universe.

28 Re: Fine tuning of the Universe Sun Jan 08, 2023 12:49 pm

Re: Fine tuning of the Universe Sun Jan 08, 2023 12:49 pm

Otangelo

Admin

JULY 25, 2017 / CALUM MILLER

4. Justifying premise 4

There is often a great deal of misunderstanding over what, precisely, is meant by “fine tuning”. What is the universe fine tuned for? How can the universe be fine tuned for life if most of it is uninhabitable? Here, I hope to clarify the issue by giving a definition and defence of the truth of proposition F. This is that the laws of nature, the constants of physics and the initial conditions of the universe must have a very precise form or value for the universe to permit the existence of embodied moral agents. The evidence for each of these three groups of fine tuned conditions will be slightly different, as will the justification for premise 5 for each. I consider the argument from the laws of nature to be the most speculative and the weakest, and so include it here primarily for completeness.

4.1 The laws of nature

While there does not seem to be a quantitative measure in this case, it does seem as though our universe has to have particular kinds of laws to permit the existence of embodied moral agents. Laws comparable to ours are necessary for the specific kind of materiality needed for EMAs – Collins gives five examples of such laws: gravity, the strong nuclear force, electromagnetism, Bohr’s Quantization rule and the Pauli Exclusion Principle.

4.1.1 Gravity

Gravity, the universal attraction force between material objects, seems to be a necessary force for complex self-reproducing material systems. Its force between two material objects is given by the classical Newtonian law: F = Gm1m2/r², where G is the gravitational constant (equal to 6.672 x 10-11 N(m/kg)², this will be of relevance also for the argument from the values of constants), m1 and m2 are the masses of the two objects, and r is the distance between them. If there were no such long-range attractive force, there could be no sustenance of stars (the high temperature would cause dispersion of the matter without a counteracting attractive force) and hence no stable energy source for the evolution of complex life. Nor would there be planets, or any beings capable of staying on planets to evolve into EMAs. And so it seems that some similar law or force is necessary for the existence of EMAs.

4.1.2 The strong nuclear force

This is the force which binds neutrons and protons in atomic nuclei together, and which has to overcome the electromagnetic repulsion between protons. However, it must also have an extremely short range to limit atom size, and so its force must diminish much more rapidly than gravity or electromagnetism. If not, its sheer strength (1040 times the strength of gravity between neutrons and protons in a nucleus) would attract all the matter in the universe together to form a giant black hole. If this kind of short-range, extremely strong force (or something similar) did not exist, the kind of chemical complexity needed for life and for star sustenance (by nuclear fusion) would not be possible. Again, then, this kind of law is necessary for the existence of EMAs.

4.1.3 Electromagnetism

Electromagnetic forces are the primary attractive forces between electrons and nuclei, and thus are critical for atomic stability. Moreover, energy transmission from stars would be impossible without some similar force, and thus there could be no stable energy source for life, and hence embodied moral agents.

4.1.4 Bohr’s Quantization Rule

Danish physicist Niels Bohr proposed this at the beginning of the 20th century, suggesting that electrons can only occupy discrete orbitals around atoms. If this were not the case, then electrons would gradually reduce their energy (by radiation) and eventually (though very rapidly) lose their orbits. This would preclude atomic stability and chemical complexity, and so also preclude the existence of EMAs.

4.1.5 The Pauli Exclusion Principle

This principle, formalised in 1925 by Austrian physicist Wolfgang Pauli, says that no two particles with half-integer spin (fermions) can occupy the same quantum state at the same time. Since each orbital has only two possible quantum states, this implies that only two electrons can occupy each orbital. This prevents electrons from all occupying the lowest atomic orbital, and so facilitates complex chemistry.[2]

4.1.6 Conclusion

As noted, it is hard to give any quantification when discussing how probable these laws (aside from their strength) are, given different explanatory hypotheses. Similarly, there may be some doubts about the absolute necessity of some. But the fact nevertheless remains that the laws in general must be so as to allow for complex chemistry, stable energy sources and therefore the complex materiality needed for embodied moral agents. And it is far from clear that any arrangement or form of laws in a material universe would be capable of doing this. There has to be a particular kind of materiality, with laws comparable to these, in order for the required chemical and therefore biological complexity. So, though there is not the kind of precision and power found in support for F in this case as there is for the values of the constants of physics or for the initial conditions of the universe, it can yet reasonably be said that F obtains for the laws of nature.

4.2 The constants of physics

In the laws of physics, there are certain constants which have a particular value – these being constant, as far as we know, throughout the universe. Generally, the value of the constant tends to determine the strength of a particular force, or something equivalent. An example, mentioned previously, is the gravitational constant, in Newton’s equation: F = Gm1m2/r². The value of the gravitational constant thus, along with the masses and distance between them, determines the force of gravity.

Following Collins, I will call a constant fine-tuned “if the width of its life-permitting range, Wr, is very small in comparison to the width, WR, of some properly chosen comparison range: that is, Wr/WR << 1.” This will be explicated more fully later, but for now we will use standard comparison ranges in physics. An approximation to a standard measure of force strengths is comparing the strength of the different forces between two protons in a nucleus – these will have electromagnetic, strong nuclear and gravitational forces all acting between them and so provides a good reference frame for some of our comparison ranges. Although the cases of the cosmological and gravitational constants are perhaps the two most solid cases of fine tuning, I will also briefly consider three others: the electromagnetic force, the strong nuclear force and the proton/neutron mass difference.

4.2.1 The gravitational constant

Gravity is a relatively weak force, just 1/1040 of the strength of the strong nuclear force. And it turns out that this relative weakness is crucial for life. Consider an increase in its strength by a factor of 109: in this kind of world, any organism close to our size would be crushed. Compare then, Astronomer Royal Martin Rees’ statement that “In an imaginary strong gravity world, even insects would need thick legs to support them, and no animals could get much larger”. If the force of gravity were this strong, a planet which had a gravitational pull one thousand times the size of Earth’s would only be twelve metres in diameter – and it is inconceivable that even this kind of planet could sustain life, let alone a planet any bigger.

Now, a billion-fold increase seems like a large increase – indeed it is, compared to the actual value of the gravitational constant. But there are two points to be noted here. Firstly, that the upper life-permitting bound for the gravitational constant is likely to be much lower than 109 times the current value. Indeed, it is extraordinarily unlikely that the relevant kind of life, viz. embodied moral agents, could exist with the strength of gravity being any more than 3,000 times its current value, since this would prohibit stars from lasting longer than a billion years (compared with our sun’s current age of 4.5 billion years). Further, relative to other parameters, such as the Hubble constant and cosmological constant, it has been argued that a change in gravity’s strength by “one part in 1060 of its current value” would mean that “the universe would have either exploded too quickly for galaxies and stars to form, or collapsed back in on itself too quickly for life to evolve.” But secondly, and more pertinently, both these increases are minute compared with the total range of force strengths in nature – the maximum known being that of the strong nuclear force. This does not seem to be any consistency in supposing that gravity could have been this strong; this seems like a natural upper bound to the potential strength of forces in nature. But compared to this, even a billion-fold increase in the force of gravity would represent just one part in 1031 of the possible increases.

We do not have a comparable estimate for the lower life-permitting bound, but we do know that there must be some positive gravitational force, as demonstrated above. Setting a lower bound of 0 is even more generous to fine tuning detractors than the billion-fold upper limit, but even these give us an exceptionally small value for Wr/WR, in the order of 1/1031.

4.2.2 The cosmological constant

As Collins puts it, “the smallness of the cosmological constant is widely regarded as the single greatest problem confronting current physics and cosmology.” The cosmological constant, represented by Λ, was hypothesised by Albert Einstein as part of his modified field equation. The idea is that Λ is a constant energy density of space which acts as a repulsive force – the more positive Λ is, the more gravity would be counteracted and thus the universe would expand. If Λ is too negative, the universe would have collapsed before star/galaxy formation while, if Λ is too positive, the universe would have expanded at a rate that similarly precluded star/galaxy formation. The difficulty encountered is that the vacuum energy density is supposed to act in an equivalent way to the cosmological constant, and yet the majority of posited fields (e.g. the inflaton field, the dilaton field, Higgs fields) in physics contribute (negatively or positively) to this vacuum energy density orders of magnitude higher than the life-permitting region would allow. Indeed, estimates of the contribution from these fields have given values ranging from 1053 to 10120 times the maximum life-permitting value of the vacuum energy density, ρmax.

As an example, consider the inflaton field, held to be primarily responsible for the rapid expansion in the first 10-35 to 10-37 seconds of the universe. Since the initial energy density of the inflaton field was between 1053ρmax and 10123ρmax, there is an enormous non-arbitrary, natural range of possible values for the inflaton field and for Λeff.[3] And so the fact that Λeff < Λmax represents some quite substantial fine tuning – clearly, at least, Wr/WR is very small in this case.

Similarly, the initial energy density of the Higgs field was extremely high, also around 1053ρmax. According to the Weinberg-Salem-Glashow theory, the electromagnetic and weak forces in nature merge to become an electroweak force at extremely high temperatures, as was the case shortly after the Big Bang. Weinberg and Salem introduced the “Higgs mechanism” to modern particle physics, whereby symmetry breaking of the electroweak force causes changes in the Higgs field, so that the vacuum density of the Higgs field dropped from 1053ρmax to an extremely small value, such that Λeff < Λmax.

The final major contribution to Λvac is from the zero-point energies of the fields associated with forces and elementary particles (e.g. the electromagnetic force). If space is a continuum, calculations from quantum field theory give this contribution as infinite. However, quantum field theory is thought to be limited in domain, such that it is only appropriately applied up to certain energies. However, unless this “cutoff energy” is extremely low, then there is considerable fine tuning necessary. Most physicists consider a low cutoff energy to be unlikely, and the cutoff energy is more typically taken to be the Planck energy. But if this is the case, then we would expect the energy contribution from these fields to be around 10120ρmax. Again, this represents the need for considerable fine tuning of Λeff.

One proposed solution to this is to suggest that the cosmological constant must be 0 – this would presumably be less than Λmax, and gives a ‘natural’ sort of value for the effective cosmological constant, since we can far more plausibly offer some reasons for why a particular constant has a value of 0 than for why it would have a very small, arbitrary value (given that the expected value is so large). Indeed, physicist Victor Stenger writes,

…recent theoretical work has offered a plausible non-divine solution to the cosmological constant problem. Theoretical physicists have proposed models in which the dark energy is not identified with the energy of curved space-time but rather with a dynamical, material energy field called quintessence. In these models, the cosmological constant is exactly 0, as suggested by a symmetry principle called supersymmetry. Since 0 multiplied by 10120 is still 0, we have no cosmological constant problem in this case. The energy density of quintessence is not constant but evolves along with the other matter/energy fields of the universe. Unlike the cosmological constant, quintessence energy density need not be fine-tuned.

As Stenger seems to recognise, the immediate difficulty with this is that the effective cosmological constant is not zero. We do not inhabit a static universe – our universe is expanding at an increasing rate, and so the cosmological constant must be small and positive. But this lacks the explanatory elegance of a zero cosmological constant, and so the problem reappears – why is it that the cosmological constant is so small compared to its range of possible values? Moreover, such an explanation would have to account for the extremely large cosmological constant in the early universe – if there is some kind of natural reason for why the cosmological constant has to be 0, it becomes very difficult to explain how it could have such an enormous value just after the Big Bang. And so, as Collins puts it, “if there is a physical principle that accounts for the smallness of the cosmological constant, it must be (1) attuned to the contributions of every particle to the vacuum energy, (2) only operative in the later stages of the evolution of the cosmos (assuming inflationary cosmology is correct), and (3) something that drives the cosmological constant extraordinarily close to zero, but not exactly zero, which would itself seem to require fine-tuning. Given these constraints on such a principle, it seems that, if such a principle exists, it would have to be “well-design” (or “fine-tuned”) to yield a life-permitting cosmos. Thus, such a mechanism would most likely simply reintroduce the issue of design at a different level.”

Stenger’s proposal, then, involves suggesting that Λvac + Λbare = 0 by some natural symmetry, and thus that 0 < Λeff = Λq < Λmax. It is questionable whether this solves the problem at all – plausibly, it makes it worse. Quintessence alone is not clearly less problematic than the original problem, both on account of its remarkable ad hoc-ness and its own need for fine tuning. As Lawrence Krauss notes, “As much as I like the word, none of the theoretical ideas for this quintessence seems compelling. Each is ad hoc. The enormity of the cosmological constant problem remains.” Or, see Kolda and Lyth’s conclusion that “quintessence seems to require extreme fine tuning of the potential V(φ)” – their position that ordinary inflationary theory does not require fine tuning demonstrates that they are hardly fine-tuning sympathisers. And so it is not at all clear that Stenger’s suggestion that quintessence need not be fine tuned is a sound one. Quintessence, then, has the same problems as the cosmological constant, as well as generating the new problem of a zero cosmological constant.

There is much more to be said on the problem of the cosmological constant, but that is outside the scope of this article. For now, it seems reasonable to say, contra Stenger, that Wr/WR << 1 and therefore that F obtains for the value of the cosmological constant.

4.2.3 The electromagnetic force

As explicated in 4.2.1, the strong nuclear force is the strongest of the four fundamental forces in nature, and is roughly equal to 1040G0, where G0 is the force of gravity. The electromagnetic force is roughly 1037G0, a fourteen-fold increase in which would inhibit the stability of all elements required for carbon-based life. Indeed, a slightly larger increase would preclude the formation of any elements other than hydrogen. Taking 1040G0 as a natural upper bound for the possible theoretical range of forces in nature, then, we have a value for Wr/WR of (14 x 1037)/1040 = 0.014, and therefore Wr/WR << 1. See also 4.2.4 for an argument that an even smaller increase would most probably prevent the existence of embodied moral agents.

4.2.4 The strong nuclear force

It has been suggested that the strength of the strong nuclear force is essential for carbon-based life, with the most forceful evidence for a very low Wr/WR value coming from work by Oberhummer, Csótó and Schlattl. Since we are taking the strength of the strong nuclear force (that is, 1040G0) as the upper theoretical limit (though I think a higher theoretical range is plausible), our argument here will have to depend on a hypothetical decrease in the strength of the strong nuclear force. This, I think, is possible. In short, the formation of appreciable amounts of both carbon and oxygen in stars was first noted by Fred Hoyle to depend on several factors, including the position of the 0+ nuclear resonance states in carbon, the positioning of a resonance state in oxygen, and 8Be’s exceptionally long lifetime. These, in turn, depend on the strengths of the strong nuclear force and the electromagnetic force. And thus, Oberhummer et al concluded,

[A] change of more than 0.5% in the strength of the strong interaction or more than 4% in the strength of the [electromagnetic] force would destroy either nearly all C or all O in every star. This implies that irrespective of stellar evolution the contribution of each star to the abundance of C or O in the [interstellar medium] would be negligible. Therefore, for the above cases the creation of carbon-based life in our universe would be strongly disfavoured.

Since a 0.5% decrease in the strong nuclear force strength would prevent the universe from permitting the existence of EMAs, then, it seems we can again conclude that F obtains for the strong nuclear force.

4.2.5 The proton/neutron mass difference

Our final example is also related to nuclear changes in stars, and concerns the production of helium. Helium production depends on production of deuterium (hydrogen with a neutron added to the proton in the nucleus), the nucleus of which (a deuteron) is formed by the following reaction:

Proton + proton -> deuteron + positron + electron neutrino + 0.42 MeV of energy

Subsequent positron/electron annihilation causes a release of around 1 MeV of additional energy. The feasibility of this reaction depends on its exothermicity, but if the neutron were heavier by 1.4 MeV (around 1/700 of its actual mass) it would no longer be an exothermic reaction. Thus, it seems plausible to suggest that we have another instance of fine tuning here, where a change in 1 part in 700 of the mass of the neutron would prohibit life.

4.2.6 Conclusion

In contrast with the fine tuning of the laws of nature, we here have some reasonable quantitative estimates for the fine tuning of the universe. We have relatively reliable judgments on the life-permitting range of values for the different constants, along with some non-arbitrary, natural comparison ranges. This allows us to calculate (albeit crudely) some measures of Wr/WR, and therefore to establish the veracity of F for several different constants of physics. Several things must be noted here: firstly, that we have been relatively generous to detractors in our estimations (where they have been given in full, e.g. in 4.2.3) – it is likely that the life-permitting ranges for each of these constants is smaller than we have intimated here.

Secondly, we need not assume that all of these values for constants are independent of each other. It may be that some instances of fine tuned constants are all closely linked, such that the proton/neutron mass difference is dependent on, for example, the strong nuclear force. Indeed, there are almost certainly different examples of fine tuning given in wider literature which cannot be considered independent examples of fine tuning. To this end, I have tried to present examples from as wide a range as possible, and for which claims of interdependence are entirely speculative and hopeful, rather than grounded in evidence. Moreover, even the serial dependence of each of these on another does not provide a solution – we would still be left with one fine tuned constant, for which Wr/WR is extremely small. This alone would be sufficient to justify premise 2. What would be needed to undercut all these different instances of fine tuning is some natural function which not only explained all of them, but which was itself significantly more likely (on a similar probabilistic measure) to generate life-permitting values for all the constants when considered in its most simple form.[4]

Finally, we are not assuming that, on the theistic model, the constants are directly set by a divine act of God. It may well be dependent on a prior physical mechanism which itself may have been instantiated directly by God, or which may be dependent on yet another physical process. So, for example, if quintessence did turn out to be well substantiated, this would be perfectly compatible with the design hypothesis, and would not diminish the argument from fine tuning. All it would mean is that the need for fine tuning would be pushed back a step. Quintessence may, in turn, be dependent on another fine-tuned process, and so on. Thus, we need not consider caricatures of the fine tuning argument which suppose that advocates envisage a universe all but finished, with just a few constants (like those discussed above) left to put in place, before God miraculously tweaks these forces and masses to give the final product.

It therefore seems to me to be abundantly clear that F obtains for the constants of physics, and thus that premise 4 is true. The argument that F obtains in this case seems to me far clearer than in the case of the laws of nature – if one is inclined to accept the argument of section 4.1, it follows a fortiori that the argument of 4.2 is sound.

4.3 The initial conditions of the universe

Our final type of fine tuning is that of the initial conditions of the universe. In particular, the exceedingly low entropy at the beginning of the universe has become especially difficult to explain without recourse to some kind of fine tuning. Though arguments have been made for the necessity of fine tuning of other initial conditions, we will limit our discussion here to the low entropy state as elaborated by, among others, Roger Penrose. In short, this uses the idea of phase space – a measure of the possible configurations of mass-energy in a system. If we apply the standard measure of statistical mechanics to find the probability of the early universe’s entropy occupying the particular volume of phase space compatible with life, we come up with an extraordinarily low figure. As Penrose explains, “In order to produce a universe resembling the one in which we live, the Creator would have to aim for an absurdly tiny volume of the phase space of possible universes” – this is in the order of 1/10x, where x = 10123, based on Penrose’s calculations. Here, again, the qualifications of 4.2.6 apply, viz. that it may be the case (indeed, probably is) that the initial condition is dependent on some prior process, and that the theistic hypothesis is not necessarily envisaging a direct interference by God. The responses to these misconceptions of the fine tuning argument are detailed there. It seems, then, as though we have some additional evidence for premise 4 here, evidence with substantial force.

4.4 Conclusion

In sum, then, I think we have given good reason to accept premise 4 of the basic argument. This is that the laws of nature, the constants of physics and the initial conditions of the universe must have a very precise form or value for the universe to permit the existence of embodied life. I note that the argument would still seemingly hold even if one of these conditions obtained, though I think we have good reason to accept the whole premise. We have found, at least for the constants of physics and the initial conditions of the universe, that the life-permitting range is extremely small relative to non-arbitrary, standard physical comparison ranges, and that this is quantifiable in many instances. Nevertheless, it has not been the aim of this section to establish a sound comparison range that will come later. The key purpose of this section was to give a scientific underpinning to the premise, give an introduction to the scientific issues involved and the kinds of fine tuning typically thought to be pertinent.

We have seen that attempts to explain the fine tuning typically only move the fine tuning back a step or, worse still, amplify the problem, and we have little reason to expect this pattern to change. One such attempt, quintessence, was discussed in section 4.2.2, and was demonstrated to require similar fine tuning to the cosmological constant value it purportedly explained. Moreover, quintessence, in particular, raised additional problems that were not present previously. Though we have not gone into detail on purported explanations of other examples, it ought to be noted that these tend to bring up the same problems.

A wide range of examples have been considered, such that claims of interdependence of all the variables are entirely conjectural. As explained in 4.2.6, even if there was serial dependence of the laws, constants and conditions on each other, there would still be substantial fine tuning needed, with the only way to avoid this being an even more fundamental, natural law for which an equiprobability measure would yield a relatively high value for Wr/WR, and of which all our current fundamental laws are a direct function. The issue of dependence will be discussed further in a later section.

Finally, it will not suffice to come up with solutions to some instances of fine tuning and extrapolate this to the conclusion that all of them must have a solution. I have already noted that some cases of fine tuning in wider literature (and plausibly in this article) cannot be considered independent cases – that does not warrant us in making wild claims, far beyond the evidence, that all the instances will eventually be resolved by some grand unified theory. It is likely that some putative examples of fine tuning may turn out to be seriously problematic examples in the future – that does not mean that they all are. As Leslie puts it, “clues heaped upon clues can constitute weighty evidence despite doubts about each element in the pile”.

I conclude, therefore, that we are amply justified in accepting premise 4 of the basic fine tuning argument, as outlined in section 3.2.

Footnotes

2. It is likely that the laws mentioned in 4.1.4 and 4.1.5 are dependent on more fundamental laws governing quantum mechanics. See 4.2.6 and 4.4 for brief discussions of this. ^

3. This is the effective cosmological constant, which we could say is equal to Λvac + Λbare + Λq, where Λvac is the contribution to Λ from the vacuum energy density, Λbare is the intrinsic value of the cosmological constant, and Λq is the contribution from quintessence – this will be returned to. ^

4. See later for the assumption of natural variables when assigning probabilities. ^

https://web.archive.org/web/20171026023354/https://calumsblog.com/2017/07/25/full-defence-of-the-fine-tuning-argument-part-4/

29 Re: Fine tuning of the Universe Thu Mar 21, 2024 4:53 pm

Re: Fine tuning of the Universe Thu Mar 21, 2024 4:53 pm

Otangelo

Admin

https://www.richardcarrier.info/archives/20661?fbclid=IwAR1vwqKIvterhsYXkahn9p6oO7nJ9TrgR7nZ9yYNx1RwURyE-lCWoj5vXZU

1. Richard Carrier argues that Bayesian reasoning actually disfavors the existence of God when applied to the fine-tuning argument. He suggests that the fine-tuning of the universe, which is ostensibly improbable, becomes expected under naturalism due to the vastness and age of the universe.

Counter-Argument: The Bayesian approach actually supports theism when we consider the prior probability of a universe capable of supporting life. The fine-tuning necessary for life exceeds what we might expect from chance alone, given the specific and narrow conditions required. Therefore, theism provides a better prior probability because it posits a fine-tuner with intent, making the observation of fine-tuning more expected under theism than under naturalism.

2. Carrier points out what he considers a hidden premise in the fine-tuning argument: that God requires less luck than natural processes to explain the fine-tuning.

Counter-Argument: The "hidden premise" isn't hidden or a premise, but rather an inference from the observed fine-tuning. The complexity and specificity of the conditions necessary for life imply design, as they mirror human experiences of designed systems, which are known to come from intelligent agents. Therefore, positing an intelligent fine-tuner is not about luck but about aligning with our understanding of how complex, specific conditions arise.

3. Carrier argues that a theist might gerrymander their concept of God to fit the evidence, making God unfalsifiable and the theory weak.

Counter-Argument: The concept of God is not arbitrarily adjusted but is derived from philosophical and theological traditions. The fine-tuning argument doesn't redefine God to fit the evidence but uses established concepts of God's nature (omnipotence, omniscience, benevolence) to explain the fine-tuning as a deliberate act of creation, which is consistent with theistic doctrine.

4. Carrier claims that the probability logic used in the fine-tuning argument is flawed, as it fails to account for the naturalistic explanations that could account for the observed fine-tuning without invoking a deity.

Counter-Argument: while naturalistic explanations are possible, they often lack the explanatory power and simplicity provided by the theistic explanation. The principle of Occam's Razor, which favors simpler explanations, can be invoked here: positing a single intelligent cause for the fine-tuning is simpler and more coherent than postulating a multitude of unobserved naturalistic processes that would need to align perfectly to produce the fine-tuned conditions.

5. Carrier suggests that the fine-tuning argument misrepresents theistic predictions about the universe, making them seem more aligned with the evidence than they are.

Counter-Argument: Theism, particularly in its sophisticated philosophical forms, does not make specific predictions about the physical constants of the universe but rather about the character of the universe as being orderly, rational, and conducive to life. The fine-tuning we observe is consistent with a universe created by an intelligent, purposeful being, as posited by many theistic traditions.

While Carrier presents a comprehensive critique of the fine-tuning argument from a naturalistic perspective, counter-arguments rest on the inference to the best explanation, the coherence of theistic explanations with observed fine-tuning, and philosophical and theological considerations about the nature of a creator God.

30 Re: Fine tuning of the Universe Mon Apr 08, 2024 7:53 am

Re: Fine tuning of the Universe Mon Apr 08, 2024 7:53 am

Otangelo

Admin

Answering objections to the fine-tuning argument

Claim: The universe is rather hostile to life, than life-permitting

Reply: While its true that the permissible conditions exist only in a tiny region of our universe, but this does not negate the astounding simulations required to forge those circumstances. The entire universe was plausibly required as a cosmic incubator to birth and nurture this teetering habitable zone. To segregate our local premises from the broader unfolding undermines a unified and holistic perspective. The anthropic principle alone is a tautological truism. It does not preclude the rationality of additional causal explanations that provide a coherent account of why these propitious conditions exist. Refusing to contemplate ulterior forces based solely on this principle represents an impoverished philosophy. The coherent language of math and physics undergirding all existence betrays the artifacts of a cogent Mind. To solipsistically reduce this to unbridled chance defers rather than resolving the depth of its implications. While an eternal uncreated cause may appear counterintuitive, it arises from the philosophical necessity of avoiding infinite regression. All finite existences require an adequate eternal ground. Dismissing this avenue simply transfers the complexity elsewhere without principled justification. The extraordinary parameters and complexity we witness provide compelling indicators of an underlying intention and orchestrating intelligence that merits serious consideration, however incrementally it may be grasped. To a priori reject this speaks more to metaphysical preferences than impartial weighing of empirical signposts.

Claim: All these fine-tuning cases involve turning one dial at a time, keeping all the others fixed at their value in our Universe. But maybe if we could look behind the curtains, we’d find the Wizard of Oz moving the dials together. If you let more than one dial vary at a time, it turns out that there is a range of life-permitting universes. So the Universe is not fine-tuned for life.

Reply: The myth that fine-tuning in the universe's formation involved the alteration of a single parameter is widespread yet baseless. Since Brandon Carter's seminal 1974 paper on the anthropic principle, which examined the delicate balance between the proton mass, the electron mass, gravity, and electromagnetism, it's been clear that the universe's physical constants are interdependent. Carter highlighted how the existence of stars capable of both radiative and convective energy transfer is pivotal for the production of heavy elements and planet formation, which are essential for life.

William Press and Alan Lightman later underscored the significance of these constants in 1983, pointing out that for stars to produce photons capable of driving chemical reactions, a specific "coincidence" in their values must exist. This delicate balance is critical because altering the cosmic 'dials' controlling the mass of fundamental particles such as up quarks, down quarks, and electrons can dramatically affect atomic structures, rendering the universe hostile to life as we know it.

The term 'parameter space' used by physicists refers to a multidimensional landscape of these constants. The bounds of this space range from zero mass, exemplified by photons, to the upper limit of the Planck mass, which is about 2.4 × 10^22 times the mass of the electron—a figure so astronomically high that it necessitates a logarithmic scale for comprehension. Within this scale, each increment represents a tenfold increase.

Stephen Barr's research takes into account the lower mass bounds set by the phenomenon known as 'dynamical breaking of chiral symmetry,' which suggests that particle masses could be up to 10^60 times smaller than the Planck mass. This expansive range of values on each axis of our 'parameter block' underscores the vastness of the constants' possible values and the precise tuning required to reach the balance we observe in our universe.

While altering any single parameter would require adjustments to other parameters to maintain the delicate balance necessary for life, this interdependence does not arise from a physical necessity for the other constants to change in response to a change in one constant. The interdependence is more in the sense that if one parameter is changed, the others would need to be adjusted to maintain the specific conditions required for the existence of life. However, it is possible to change one constant while keeping all others fixed, even though such a scenario would likely result in a universe inhospitable to life. This distinction is important because it highlights the remarkable fine-tuning of our universe's parameters. Each constant could theoretically take on a vast range of values, the "parameter space" spanning many orders of magnitude. The fact that our universe's constants are set at the precise values required for the formation of stars, heavy elements, and ultimately life, is what makes the fine-tuning so remarkable and the subject of ongoing inquiry.

Claim: If their values are not independent of each other, those values drop and their probabilities wouldn't be multiplicative or even additive; if one changed the others would change.

Reply: This argument fails to recognize the profound implications of interdependent probabilities in the context of the universe's fine-tuning. If the values of these cosmological constants are not truly independent, it does not undermine the design case; rather, it strengthens it. Interdependence among the fundamental constants and parameters of the universe suggests an underlying coherence and interconnectedness that defies mere random chance. It implies that the values of these constants are inextricably linked, governed by a delicate balance and harmony that allows for the existence of a life-permitting universe. The fine-tuning of the universe is not a matter of multiplying or adding independent probabilities; it is a recognition of the exquisite precision and fine-tuning required for the universe to support life as we know it. The interdependence of these constants only amplifies the complexity of this fine-tuning, making it even more remarkable and suggestive of a designed implementation. The values of these constants are truly independent and could take any arbitrary combination. The scientific evidence we currently have does not point to the physical constants and laws of nature being derived from or contingent upon any deeper, more foundational principle or entity. As far as our present understanding goes, these constants and laws appear to be the foundational parameters and patterns that define and govern the behavior of the universe itself. Their specific values are not inherently constrained or interdependent. They are independent variables that could theoretically take on any alternative values. If these constants like the speed of light, gravitational constant, masses of particles etc. are the bedrock parameters of reality, not contingent on any deeper principles or causes, then one cannot definitively rule out that they could have held radically different values not conducive to life as we know it. Since that is the case, and a life-conducing universe depends on interdependent parameters, the likelihood of a life-permitting universe is even more remote, rendering our existence a cosmic fluke of incomprehensible improbability. However, the interdependence of these constants suggests a deeper underlying principle, a grand design that orchestrates their values in a harmonious and life-sustaining symphony. Rather than diminishing the argument for design, the interdependence of cosmological constants underscores the incredible complexity and precision required for a universe capable of supporting life. It highlights the web of interconnected factors that must be finely balanced, pointing to the existence of a transcendent intelligence that has orchestrated the life-permitting constants with breathtaking skill and purpose.

Claim: The puddle adapted to the natural conditions. Not the other way around.

Reply: Douglas Adams Puddle thinking: Without fine-tuning of the universe, there would be no puddle to fit the hole, because there would no hole in the first place. The critique of Douglas Adams' puddle analogy centers on its failure to acknowledge the necessity of the universe's fine-tuning for the existence of any life forms, including a hypothetical sentient puddle. The analogy suggests that life simply adapts to the conditions it finds itself in, much like a puddle fitting snugly into a hole. However, this perspective overlooks the fundamental prerequisite that the universe itself must first be conducive to the emergence of life before any process of adaptation can occur. The initial conditions of the universe, particularly those set in motion by the Big Bang, had to be precisely calibrated for the universe to develop beyond a mere expanse of hydrogen gas or collapse back into a singularity. The rate of the universe's expansion, the balance of forces such as gravity and electromagnetism, and the distribution of matter all had to align within an incredibly narrow range to allow for the formation of galaxies, stars, and eventually planets.

Without this fine-tuning, the very fabric of the universe would not permit the formation of complex structures or the chemical elements essential for life. For instance, carbon, the backbone of all known life forms, is synthesized in the hearts of stars through a delicate process that depends on the precise tuning of physical constants. The emergence of a puddle, let alone a reflective one, presupposes a universe where such intricate processes can unfold. Moreover, the argument extends to the rate of expansion of the universe post-Big Bang, which if altered even slightly, could have led to a universe that expanded too rapidly for matter to coalesce into galaxies and stars, or too slowly, resulting in a premature collapse. In such universes, the conditions necessary for life, including the existence of water and habitable planets, would not be met.

The puddle analogy fails to account for the antecedent conditions necessary for the existence of puddles or any life forms capable of evolution and adaptation. The fine-tuning of the universe is not just a backdrop against which life emerges; it is a fundamental prerequisite for the existence of a universe capable of supporting life in any form. Without the precise fine-tuning of the universe's initial conditions and physical constants, there would be no universe as we know it, and consequently, no life to ponder its existence or adapt to its surroundings.

Claim: There is only one universe to compare with: ours

Response: There is no need to compare our universe to another. We do know the value of Gravity G, and so we know what would have happened if it had been weaker or stronger (in terms of the formation of stars, star systems, planets, etc). The same goes for the fine-structure constant, other fundamental values etc. If they were different, there would be no life. We know that the subset of life-permitting conditions (conditions meeting the necessary requirements) is extremely small compared to the overall set of possible conditions. So it is justified to ask: Why are they within the extremely unlikely subset that eventually yields stars, planets, and life-sustaining planets?

Luke Barnes: Physicists have discovered that a small number of mathematical rules account for how our universe works. Newton’s law of gravitation, for example, describes the force of gravity between any two masses separated by any distance. This feature of the laws of nature makes them predictive – they not only describe what we have already observed; they place their bets on what we observe next. The laws we employ are the ones that keep winning their bets. Part of the job of a theoretical physicist is to explore the possibilities contained within the laws of nature to see what they tell us about the Universe, and to see if any of these scenarios are testable. For example, Newton’s law allows for the possibility of highly elliptical orbits. If anything in the Solar System followed such an orbit, it would be invisibly distant for most of its journey, appearing periodically to sweep rapidly past the Sun. In 1705, Edmond Halley used Newton’s laws to predict that the comet that bears his name, last seen in 1682, would return in 1758. He was right, though didn’t live to see his prediction vindicated. This exploration of possible scenarios and possible universes includes the constants of nature. To measure these constants, we calculate what effect their value has on what we observe. For example, we can calculate how the path of an electron through a magnetic field is affected by its charge and mass, and using this calculation we can we work backward from our observations of electrons to infer their charge and mass. Probabilities, as they are used in science, are calculated, relative to some set of possibilities; think of the high-school definition of a dozen (or so) reactions to fine-tuning probability as ‘favourable over possible’. We’ll have a lot more to say about probability in Reaction (o); here we need only note that scientists test their ideas by noting which possibilities are rendered probable or improbable by the combination of data and theory. A theory cannot claim to have explained the data by noting that, since we’ve observed the data, its probability is one. Fine-tuning is a feature of the possible universes of theoretical physics. We want to know why our Universe is the way it is, and we can get clues by exploring how it could have been, using the laws of nature as our guide. A Fortunate Universe Page 239 Link

Question: Is the Universe as we know it due to physical necessity? Do we know if other conditions and fine-tuning parameters were even possible?

Answer: The Standard Model of particle physics and general relativity do not provide a fundamental explanation for the specific values of many physical constants, such as the fine-structure constant, the strong coupling constant, or the cosmological constant. These values appear to be arbitrary from the perspective of our current theories.

"The Standard Model of particle physics describes the strong, weak, and electromagnetic interactions through a quantum field theory formulated in terms of a set of phenomenological parameters that are not predicted from first principles but must be determined from experiment." - J. D. Bjorken and S. D. Drell, "Relativistic Quantum Fields" (1965)

"One of the most puzzling aspects of the Standard Model is the presence of numerous free parameters whose values are not predicted by the theory but must be inferred from experiment." - M. E. Peskin and D. V. Schroeder, "An Introduction to Quantum Field Theory" (1995)

"The values of the coupling constants of the Standard Model are not determined by the theory and must be inferred from experiment." - F. Wilczek, "The Lightness of Being" (2008)

"The cosmological constant problem is one of the greatest challenges to our current understanding of fundamental physics. General relativity and quantum field theory are unable to provide a fundamental explanation for the observed value of the cosmological constant." - S. M. Carroll, "The Cosmological Constant" (2001)

"The fine-structure constant is one of the fundamental constants of nature whose value is not explained by our current theories of particle physics and gravitation." - M. Duff, "The Theory Formerly Known as Strings" (2009)

These quotes from prominent physicists and textbooks clearly acknowledge that the Standard Model and general relativity do not provide a fundamental explanation for the specific values of many physical constants.

As the universe cooled after the Big Bang, symmetries were spontaneously broken, "phase transitions" occurred, and discontinuous changes occurred in the values of various physical parameters (e.g., in the strengths of certain fundamental interactions or in the masses of certain species) . of the particle). So something happened that shouldn't/couldn't happen if the current state of things was based on physical necessities. Breaking symmetry is exactly what shows that there was no physical necessity for things to change in the early universe. There was a transition zone until one arrived at the composition of the basic particles that make up all matter. The current laws of physics did not apply [in the period immediately after the Big Bang]. They only became established when the density of the universe fell below the so-called Planck density. There is no physical constraint or necessity that causes the parameter to have only the updated parameter. There is no physical principle that says physical laws or constants must be the same everywhere and always. Since this is so, the question arises: What instantiated the life-permitting parameters? There are two options: luck or a lawmaker.

Standard quantum mechanics is an empirically successful theory that makes extremely accurate predictions about the behavior of quantum systems based on a set of postulates and mathematical formalism. However, these postulates themselves are not derived from a more basic theory - they are taken as fundamental axioms that have been validated by extensive experimentation. So in principle, there is no reason why an alternative theory with different postulates could not reproduce all the successful predictions of quantum mechanics while deviating from it for certain untested regimes or hypothetical situations. Quantum mechanics simply represents our current best understanding and extremely successful modeling of quantum phenomena based on the available empirical evidence. Many physicists hope that a theory of quantum gravity, which could unify quantum mechanics with general relativity, may eventually provide a deeper foundational framework from which the rules of quantum mechanics could emerge as a limiting case or effective approximation. Such a more fundamental theory could potentially allow or even predict deviations from standard quantum mechanics in certain extreme situations. It's conceivable that quantum behaviors could be different in a universe with different fundamental constants, initial conditions, or underlying principles. The absence of deeper, universally acknowledged principles that necessitate the specific form of quantum mechanics as we know it leaves room for theoretical scenarios about alternative quantum realities. Several points elaborate on this perspective:

Contingency on Constants and Conditions: The specific form and predictions of quantum mechanics depend on the values of fundamental constants (like the speed of light, Planck's constant, and the gravitational constant) and the initial conditions of the universe. These constants and conditions seem contingent rather than necessary, suggesting that different values could give rise to different physical laws, including alternative quantum behaviors.

Lack of a Final Theory: Despite the success of quantum mechanics and quantum field theory, physicists do not yet possess a "final" theory that unifies all fundamental forces and accounts for all aspects of the universe, such as dark matter and dark energy. This indicates that our current understanding of quantum mechanics might be an approximation or a special case of a more general theory that could allow for different behaviors under different conditions.

Theoretical Flexibility: Theoretical physics encompasses a variety of models and interpretations of quantum mechanics, some of which (like many-worlds interpretations, pilot-wave theories, and objective collapse theories) suggest fundamentally different mechanisms underlying quantum phenomena. This diversity of viable theoretical frameworks indicates a degree of flexibility in how quantum behaviors could be conceptualized.

Philosophical Openness: From a philosophical standpoint, there's no definitive argument that precludes the possibility of alternative quantum behaviors. The nature of scientific laws as descriptions of observed phenomena, rather than prescriptive or necessary truths, allows for the conceptual space in which these laws could be different under different circumstances or in different universes.

Exploration of Alternative Theories: Research in areas like quantum gravity, string theory, and loop quantum gravity often explores regimes where classical notions of space, time, and matter may break down or behave differently. These explorations hint at the possibility of alternative quantum behaviors in extreme conditions, such as near singularities or at the Planck scale.

Since our current understanding of quantum mechanics is not derived from a final, unified theory of everything grounded in deeper fundamental principles, it leaves open the conceptual possibility of alternative quantum behaviors emerging under different constants, conditions, or theoretical frameworks. The apparent fine-tuning of the fundamental constants and initial conditions that permit a life-sustaining universe could potentially hint at an underlying order or purpose behind the specific laws of physics as we know them. The cosmos exhibits an intelligible rational structure amenable to minds discerning the mathematical harmonies embedded within the natural order. From a perspective of appreciation for the exquisite contingency that allows for rich complexity emerging from simple rules, the subtle beauty and coherence we find in the theoretically flexible yet precisely defined quantum laws point to a reality imbued with profound elegance. An elegance that, to some, evokes intimations of an ultimate source of reasonability. Exploring such questions at the limits of our understanding naturally leads inquiry towards profound archetypal narratives and meaning-laden metaphors that have permeated cultures across time - the notion that the ground of being could possess the qualities of foresight, intent, and formative power aligned with establishing the conditions concordant with the flourishing of life and consciousness. While the methods of science must remain austerely focused on subjecting conjectures to empirical falsification, the underdetermination of theory by data leaves an opening for metaphysical interpretations that find resonance with humanity's perennial longing to elucidate our role in a potentially deeper-patterned cosmos. One perspective that emerges in this context is the notion of a universe that does not appear to be random in its foundational principles. The remarkable harmony and order observed in the natural world, from the microscopic realm of quantum particles to the macroscopic scale of cosmic structures, suggest an underlying principle of intelligibility. This intelligibility implies that the universe can be understood, predicted, and described coherently, pointing to a universe that is not chaotic but ordered and governed by discernible laws. While science primarily deals with the 'how' questions concerning the mechanisms and processes governing the universe, these deeper inquiries touch on the 'why' questions that science alone may not fully address. The remarkable order and fine-tuning of the universe often lead to the contemplation of a higher order or intelligence, positing that the intelligibility and purposeful structure of the universe might lead to its instantiation by a mind with foresight.

Question: If life is considered a miraculous phenomenon, why is it dependent on specific environmental conditions to arise?

Reply: Omnipotence does not imply the ability to achieve logically contradictory outcomes, such as creating a stable universe governed by chaotic laws. Omnipotence is bounded by the coherence of what is being created.

The concept of omnipotence is understood within the framework of logical possibility and the inherent nature of the goals or entities being brought into existence. For example, if the goal is to create a universe capable of sustaining complex life forms, then certain finely tuned conditions—like specific physical constants and laws—would be inherently necessary to achieve that stability and complexity. This doesn't diminish the power of the creator but rather highlights a commitment to a certain order and set of principles that make the creation meaningful and viable. From this standpoint, the constraints and fine-tuning we observe in the universe are reflections of an underlying logical and structural order that an omnipotent being chose to implement. This order allows for the emergence of complex phenomena, including life, and ensures the universe's coherence and sustainability. Furthermore, the limitations on creating contradictory or logically impossible entities, like a one-atom tree don't represent a failure of omnipotence but an adherence to principles of identity and non-contradiction. These principles are foundational to the intelligibility of the universe and the possibility of meaningful interaction within it.

God's act of fine-tuning the universe is a manifestation of his omnipotence and wisdom, rather than a limitation. The idea is that God, in his infinite power and knowledge, intentionally and meticulously crafted the fundamental laws, forces, and constants of the universe in such a precise manner to allow for the existence of life and the unfolding of his grand plan. The fine-tuning of the universe is not a constraint on God's omnipotence but rather a deliberate choice made by an all-knowing and all-powerful Creator. The specificity required for the universe to be life-permitting is a testament to God's meticulous craftsmanship and his ability to set the stage for the eventual emergence of life and the fulfillment of his divine purposes. The fine-tuning of the universe is an expression of God's sovereignty and control over all aspects of creation. By carefully adjusting the fundamental parameters to allow for the possibility of life, God demonstrates his supreme authority and ability to shape the universe according to his will and design. The fine-tuning of the universe is not a limitation on God's power but rather a manifestation of his supreme wisdom, sovereignty, and purposeful design in crafting a cosmos conducive to the existence of life and the realization of his divine plan.

Objection: Most places in the Universe would kill us. The universe is mostly hostile to life

Response: The presence of inhospitable zones in the universe does not negate the overall life-permitting conditions that make our existence possible. The universe, despite its vastness and diversity, exhibits remarkable fine-tuning that allows life to thrive. It is vast and filled with extreme environments, such as the intense heat and radiation of stars, the freezing vacuum of interstellar space, and the crushing pressures found in the depths of black holes. However, these inhospitable zones are not necessarily hostile to life but rather a manifestation of the balance and complexity that exists within the cosmos. Just as a light bulb, while generating heat, is designed to provide illumination and facilitate various activities essential for life, the universe, with its myriad of environments, harbors pockets of habitable zones where the conditions are conducive to the emergence and sustenance of life as we know it. The presence of these life-permitting regions, such as the Earth, is a testament to the remarkable fine-tuning of the fundamental constants and laws of physics that govern our universe. The delicate balance of forces, the precise values of physical constants, and the intricate interplay of various cosmic phenomena have created an environment where life can flourish. Moreover, the existence of inhospitable zones in the universe contributes to the diversity and richness of cosmic phenomena, which in turn drive the processes that enable and sustain life. For instance, the energy generated by stars through nuclear fusion not only provides light and warmth but also drives the chemical processes that enable the formation of complex molecules, the building blocks of life. The universe's apparent hostility in certain regions does not diminish its overall life-permitting nature; rather, it underscores the balance and complexity that make life possible. The presence of inhospitable zones is a natural consequence of the laws and processes that govern the cosmos, and it is within this that pockets of habitable zones emerge, allowing life to thrive and evolve.

Objection: The weak anthropic principle explains our existence just fine. We happen to be in a universe with those constraints because they happen to be the only set that will produce the conditions in which creatures like us might (but not must) occur. So, no initial constraints = no one to become aware of those initial constraints. This gets us no closer to intelligent design.

Response: The astonishing precision required for the fundamental constants of the universe to support life raises significant questions about the likelihood of our existence. Given the exacting nature of these intervals, the emergence of life seems remarkably improbable without the possibility of numerous universes where life could arise by chance. These constants predated human existence and were essential for the inception of life. Deviations in these constants could result in a universe inhospitable to stars, planets, and life. John Leslie uses the Firing Squad analogy to highlight the perplexity of our survival in such a finely-tuned universe. Imagine standing before a firing squad of expert marksmen, only to survive unscathed. While your survival is a known fact, it remains astonishing from an objective standpoint, given the odds. Similarly, the existence of life, while a certainty, is profoundly surprising against the backdrop of the universe's precise tuning. This scenario underscores the extent of fine-tuning necessary for a universe conducive to life, challenging the principles of simplicity often favored in scientific explanations. Critics argue that the atheistic leaning towards an infinite array of hypothetical, undetectable parallel universes to account for fine-tuning while dismissing the notion of a divine orchestrator as unscientific, may itself conflict with the principle of parsimony, famously associated with Occam's Razor. This principle suggests that among competing hypotheses, the one with the fewest assumptions should be selected, raising questions about the simplicity and plausibility of invoking an infinite number of universes compared to the possibility of a purposeful design.

Objection: Using the sharpshooter fallacy is like drawing the bullseye around the bullet hole. You are a puddle saying "Look how well this hole fits me. It must have been made for me" when in reality you took your shape from your surroundings.

Response: The critique points out the issue of forming hypotheses post hoc after data have been analyzed, rather than beforehand, which can lead to misleading conclusions. The argument emphasizes the extensive fine-tuning required for life to exist, from cosmic constants to the intricate workings of cellular biology, challenging the notion that such precision could arise without intentional design. This perspective is bolstered by our understanding that intelligence can harness mathematics, logic, and information to achieve specific outcomes, suggesting that a similar form of intelligence might account for the universe's fine-tuning.

1. The improbability of a life-sustaining universe emerging through naturalistic processes, without guidance, contrasts sharply with theism, where such a universe is much more plausible due to the presumed foresight and intentionality of a divine creator.

2. A universe originating from unguided naturalistic processes would likely have parameters set arbitrarily, making the emergence of a life-sustaining universe exceedingly rare, if not impossible, due to the lack of directed intention in setting these parameters.

3. From a theistic viewpoint, a universe conducive to life is much more likely, as an omniscient creator would know precisely what conditions, laws, and parameters are necessary for life and would have the capacity to implement them.

4. When considering the likelihood of design versus random occurrence through Bayesian reasoning, the fine-tuning of the universe more strongly supports the hypothesis of intentional design over the chance assembly of life-permitting conditions.

This line of argumentation challenges the scientific consensus by questioning the sufficiency of naturalistic explanations for the universe's fine-tuning and suggesting that alternative explanations, such as intelligent design, warrant consideration, especially in the absence of successful naturalistic models to replicate life's origin in controlled experiments.

Objection: Arguments from probability are drivel. We have only one observable universe. So far the likelihood that the universe would form the way it did is 1 in 1

Response: The argument highlights the delicate balance of numerous constants in the universe essential for life. While adjustments to some constants could be offset by changes in others, the viable configurations are vastly outnumbered by those that would preclude complex life. This leads to a recognition of the extraordinarily slim odds for a life-supporting universe under random circumstances. A common counterargument to such anthropic reasoning is the observation that we should not find our existence in a finely tuned universe surprising, for if it were not so, we would not be here to ponder it. This viewpoint, however, is criticized for its circular reasoning. The analogy used to illustrate this point involves a man who miraculously survives a firing squad of 10,000 marksmen. According to the counterargument, the man should not find his survival surprising since his ability to reflect on the event necessitates his survival. Yet, the apparent absurdity of this reasoning highlights the legitimacy of being astonished by the universe's fine-tuning, particularly under the assumption of a universe that originated without intent or design. This astonishment is deemed entirely rational, especially in light of the improbability of such fine-tuning arising from non-intelligent processes.

Objection: every sequence is just as improbable as another.

Answer:The crux of the argument lies in distinguishing between any random sequence and one that holds a specific, meaningful pattern. For example, a sequence of numbers ascending from 1 to 500 is not just any sequence; it embodies a clear, deliberate pattern. The focus, therefore, shifts from the likelihood of any sequence occurring to the emergence of a particularly ordered or designed sequence. Consider the analogy of a blueprint for a car engine designed to power a BMW 5X with 100 horsepower. Such a blueprint isn't arbitrary; it must contain a precise and complex set of instructions that align with the shared understanding and agreements between the engineer and the manufacturer. This blueprint, which can be digitized into a data file, say 600MB in size, is not just any collection of data. It's a highly specific sequence of information that, when correctly interpreted and executed, results in an engine with the exact characteristics needed for the intended vehicle.

When applying this analogy to the universe, imagine you have a hypothetical device that generates universes at random. The question then becomes: What are the chances that such a device would produce a universe with the exact conditions and laws necessary to support complex life, akin to the precise specifications needed for the BMW engine? The implication is that just as not any sequence of bits will result in the desired car engine blueprint, so too not any random configuration of universal constants and laws would lead to a universe conducive to life.

Objection: You cannot assign odds to something AFTER it has already happened. The chances of us being here is 100 %

Answer: The likelihood of an event happening is tied to the number of possible outcomes it has. For events with a single outcome, such as a unique event happening, the probability is 1 or 100%. In scenarios with multiple outcomes, like a coin flip, which has two (heads or tails), each outcome has an equal chance, making the total probability 1 or 100%, as one of the outcomes must occur. To gauge the universe's capacity for events, we can estimate the maximal number of interactions since its supposed inception 13.7 billion years ago. This involves multiplying the estimated number of atoms in the universe (10^80), by the elapsed time in seconds since the Big Bang (10^16), and by the potential interactions per second for all atoms (10^43), resulting in a total possible event count of 10^139. This figure represents the universe's "probabilistic resources."

If the probability of a specific event is lower than what the universe's probabilistic resources can account for, it's deemed virtually impossible to occur by chance alone.

Considering the universe and conditions for advanced life, we find:

- The universe's at least 157 cosmological features must align within specific ranges for physical life to be possible.

- The probability of a suitable planet for complex life forming without supernatural intervention is less than 1 in 10^2400.

Focusing on the emergence of life from non-life (abiogenesis) through natural processes:

- The likelihood of forming a functional set of proteins (proteome) for the simplest known life form, which has 1350 proteins each 300 amino acids long, by chance is 10^722000.

- The chance of assembling these 1350 proteins into a functional system is about 4^3600.

- Combining the probabilities for both a minimal functional proteome and its correct assembly (interactome), the overall chance is around 10^725600.