Salamanders are amazing

http://reasonandscience.heavenforum.org/t2603-salamanders-are-amazing

The Princeton Guide to Evolution, page 3:

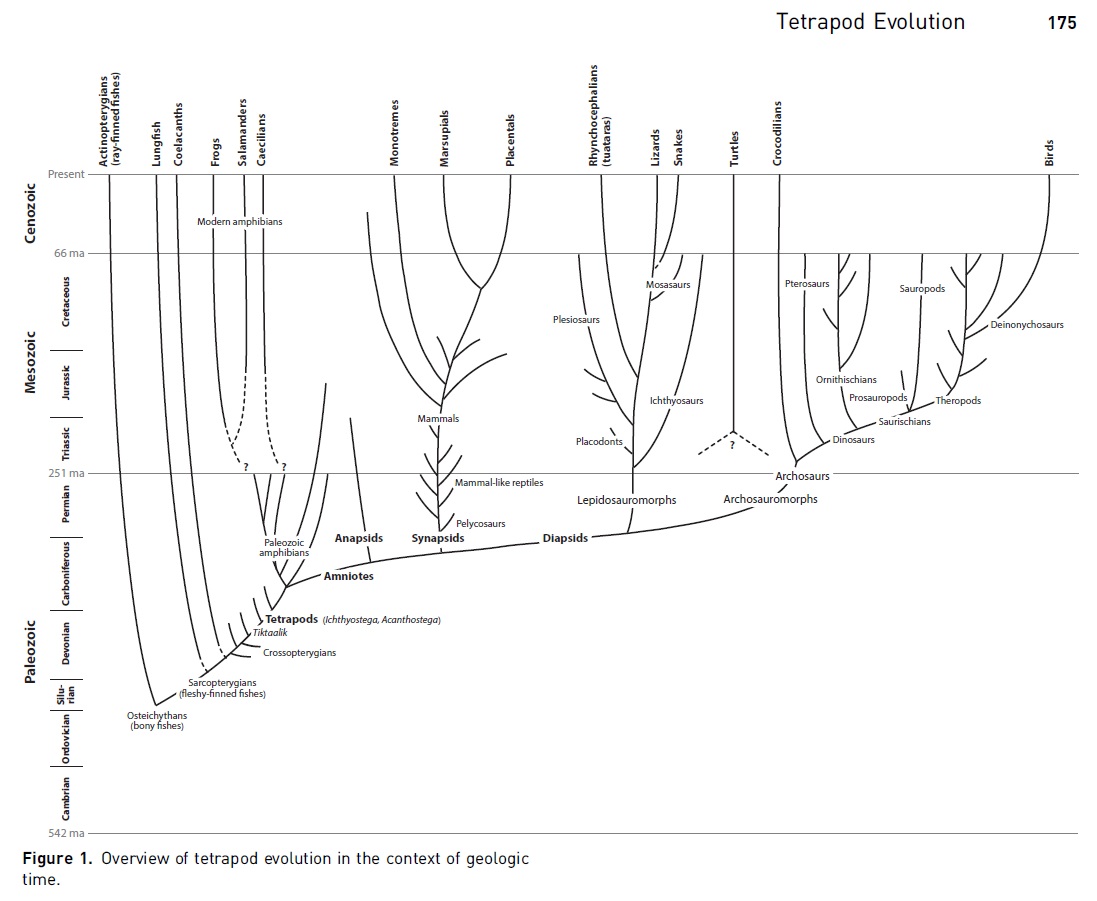

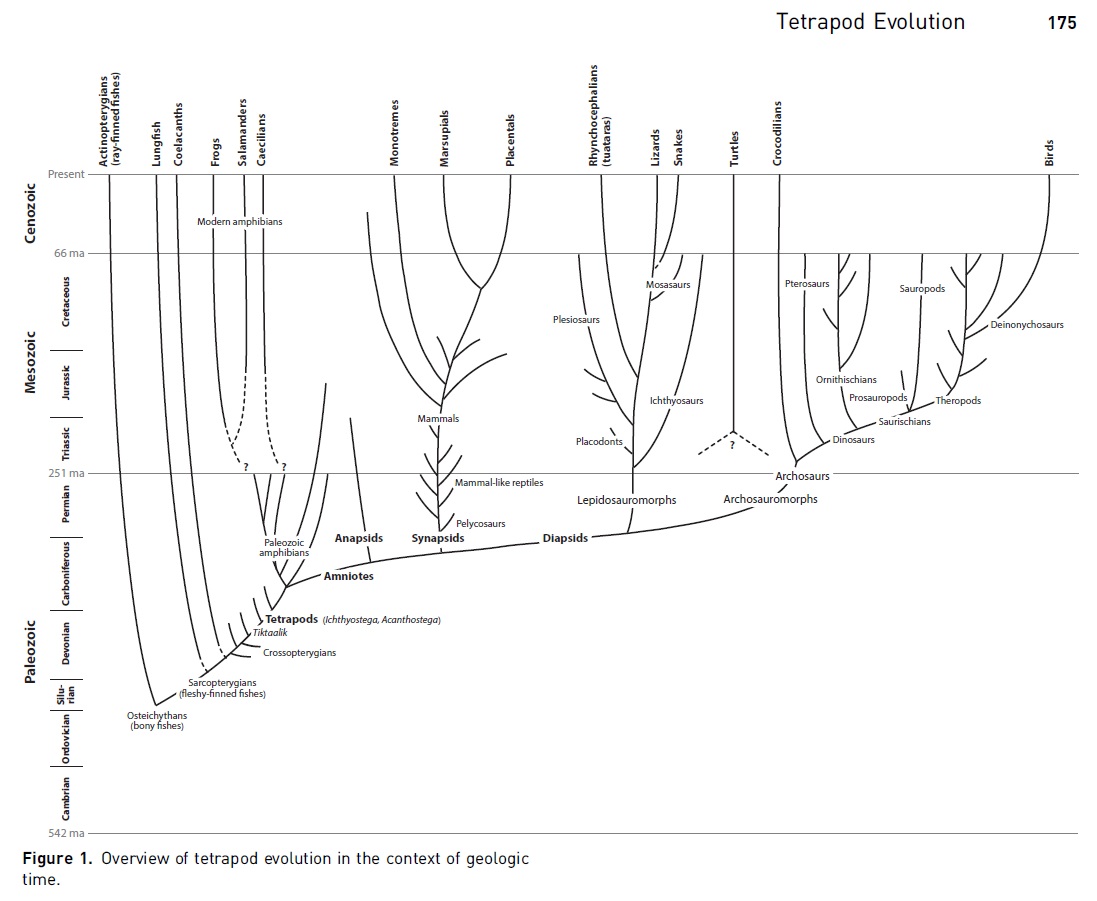

Approximately 375 million years ago, a large and vaguely salamander-like creature plodded from its aquatic home and began the vertebrate invasion of land, setting forth the chain of evolutionary events that led to the birds that fill our skies, the beasts that walk our soil, me writing this chapter, and you reading it.

Ancient Amphibian: Debate Over Origin Of Frogs And Salamanders Settled With Discovery Of Missing Link

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/05/080521131541.htm

The examination and detailed description of the fossil, Gerobatrachus hottoni (meaning Hotton's elder frog), proves the previously disputed fact that some modern amphibians, frogs and salamanders evolved from one ancient amphibian group called temnospondyls.

Salamanders have huge genomes because they lose DNA slowly

http://www.sciguru.org/newsitem/15368/salamanders-have-huge-sized-genomes-because-they-did-not-shed-their-genes

Whereas the human genome is made up of about 3.2 billion base pairs, a salamander genome may contain as many as 120 billion base pairs. Salamanders have the largest genome sizes among four-footed animals (tetrapods) and, with the exception of lungfishes, among vertebrates as a whole.

Slow DNA Loss in the Gigantic Genomes of Salamanders

https://academic.oup.com/gbe/article/4/12/1340/608259/Slow-DNA-Loss-in-the-Gigantic-Genomes-of

Salamanders have the largest genome sizes among tetrapods and, with the exception of lungfishes, among vertebrates as a whole. Genome sizes across the 624 species of salamanders range from ∼14 Gb to ∼120 Gb

Genetic elements that drive regeneration uncovered

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/04/160406140405.htm

Salamanders and fish possess genes that can enable healing of damaged tissue and even regrowth of missing limbs. The key to regeneration lies not only in the genes, but in the DNA sequences that regulate expression of those genes in response to an injury. Researchers have discovered regulatory sequences that they call ’tissue regeneration enhancer elements’ or TREEs, which can turn on genes in injury sites.

Modulation of tissue repair by regeneration enhancer elements

http://sci-hub.cc/10.1038/nature17644

How some salamanders regrow their limbs

http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2016/06/how-some-salamanders-regrow-their-limbs

The ability to grow a new limb may seem like something straight out of science fiction, but new research shows exactly how animals like salamanders and zebrafish perform this stunning feat—and how humans may share the biological machinery that lets them do it. Scientists have long known of the regenerative powers of some species of fish and amphibians: To recreate a limb or fin lost to a hungry predator, they can regrow everything from bone to muscle to blood vessels with stem cells that form at the site of the injury. But just how they do it at the genetic level is a mystery. To figure out what might be happening, scientists amputated the appendages of two ray-finned fish—zebrafish and bichir—and a salamander known as the axolotl, all of which can regrow their legs and fins. They then compared RNA from the site of the amputation. They found 10 microRNAs—small pieces of RNA that regulate gene expression—that were the same in all three species. What’s more, they seemed to function in the same way, despite the structural difference between the axolotl (pictured above) and the fishes. The finding supports an existing idea that the three master limb-replacers last shared a common ancestor about 420 million years ago, and it suggests that the evolutionary process of growing limbs is saved over time, not developed independently in separate species, the researchers report today in PLOS ONE. What does this mean for humans? If these microRNAs can be programmed to work like they do in salamanders and fish, humans could enhance their ability to heal from serious injuries. But don’t expect to get Wolverine-like powers just yet—scientists say such modifications are still a long way off.

Deep-time evolution of regeneration and preaxial polarity in tetrapod limb development

http://www.nature.com.sci-hub.bz/nature/journal/v527/n7577/full/nature15397.html

Among extant tetrapods, salamanders are unique in showing a reversed preaxial polarity in patterning of the skeletal elements of the limbs, and in displaying the highest capacity for regeneration, including full limb and tail regeneration. These features are particularly striking as tetrapod limb development has otherwise been shown to be a highly conserved process. It remains elusive whether the capacity to regenerate limbs in salamanders is mechanistically and evolutionarily linked to the aberrant pattern of limb development; both are features classically regarded as unique to urodeles. New molecular data suggest that salamander-specific orphan genes play a central role in limb regeneration and may also be involved in the preaxial patterning during limb development. Here we show that preaxial polarity in limb development was present in various groups of temnospondyl amphibians of the Carboniferous and Permian periods, including the dissorophoids Apateon and Micromelerpeton, as well as the stereospondylomorph Sclerocephalus. Limb regeneration has also been reported in Micromelerpeton , demonstrating that both features were already present together in antecedents of modern salamanders 290 million years ago. Furthermore, data from lepospondyl ‘microsaurs’ on the amniote stem indicate that these taxa may have shown some capacity for limb regeneration and were capable of tail regeneration , including re-patterning of the caudal vertebral column that is otherwise only seen in salamander tail regeneration. The data from fossils suggest that salamander-like regeneration is an ancient feature of tetrapods that was subsequently lost at least once in the lineage leading to amniotes. Salamanders are the only modern tetrapods that retained regenerative capacities as well as preaxial polarity in limb development.

Salamander Offers Two Evolutionary Quandaries: Non-Homologous Development and an ORFan

https://evolutionnews.org/2017/01/salamander_offe/

The evolution and phylogeny of crown group salamanders is plagued by homoplasy. In fact, a large a number of highly derived anatomical characters, including body elongation, tail autonomy, and life history pathways, have been demonstrated or are debated to have evolved multiple times. The findings of unique (non-homologous) development patterns, and lineage-specific genes make no sense on evolution. And attempts to explain these findings according to evolution with clever, detailed hypotheses just cause more problems. If you try to build a house on a faulty foundation, it will just get worse. Evolution is a flawed theory, and the more we learn about biology, the more evident that becomes.

No Salamander Evolution Evidence, Past or Present

http://www.icr.org/article/no-salamander-evolution-evidence-past/

Study of salamanders in ponds demonstrates 'invisible finger of evolution'

https://phys.org/news/2013-05-salamanders-ponds-invisible-finger-evolution.html

Algae that live inside the cells of salamanders are the first known vertebrate endosymbionts

https://phys.org/news/2011-04-algae-cells-salamanders-vertebrate-endosymbionts.html

Gene Thieves: Female Salamanders Hijack DNA from Multiple Males

https://www.livescience.com/59639-salamanders-steal-genes.html

In the natural world, stealing is a necessary and frequent strategy for survival. Every animal group includes opportunists that snatch others' fresh kills, pilfer nesting materials or swipe prospective mates from distracted rivals.

But only one type of animal uses thievery at the genetic level for reproduction — an all-female lineage of salamanders in the Ambystoma genus, which contains dozens of species and is widespread across North America. These females mate with multiple males from other Ambystoma species and hijack copies of their partners' genomes, researchers discovered about a decade ago. However, scientists recently found that the salamanders weren't just stealing the males' genomes. They're incorporating genetic material from males across multiple species into their own genetic code and using all of them at the same time — a process that is otherwise unheard of in animals, researchers reported in a new study.

Algae Invaders Actually Benefit Their Salamander Hosts

http://www.icr.org/article/algae-invaders-actually-benefit-their/

Xeroxed lung gene helps salamanders breathe through their skin

http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2016/01/xeroxed-lung-gene-helps-salamanders-breathe-through-their-skin

Almost all land animals need lungs to survive. The world’s largest group of salamanders is a rare exception. Now, researchers know how these amphibians came to breathe through their skin instead. A copy of a key lung gene shifted where it is active, rendering skin capable of efficient gas exchange, they reported here this week at the annual meeting of the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology. The loss of lungs represents major evolutionary change, one expected to limit the size, lifestyle, and whereabouts of any species. But the 448 species of a family of salamanders called plethodontids must not have gotten that message, as they roam across the Western Hemisphere, South Korea, and Italy; range from 25 millimeters to 27 centimeters long; and call burrows to tree tops home. So evolutionary developmental biologists tracked embryonic development of one of these species, the dusky salamander (Desmognathus fuscus), and discovered that although lungs do start to form, they never fully develop. Instead, this species produces extra blood vessels to the skin. Studies of gene activity in this and other vertebrates also revealed that there is a key gene in the vertebrate lung that exists in two copies in salamanders. That gene is active just in the lungs of lunged salamanders, but in lungless species is active in the skin, mouth, and throat as well. It codes for a protein that helps membranes be more receptive to gas exchange, and its presence in the skin and mouth helps explain why some salamanders don’t need lungs at all. Called a surfactant protein, this newly discovered protein may prove useful for treating breathing problems in people, the researchers note.

Mexican salamander helps uncover mysteries of stem cells and evolution

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/07/100711205804.htm

Scientists have been using a Mexican aquatic salamander called an axolotl to study the evolution and genetics of stem cells -- research that supports the development of regenerative medicine to treat the consequences of disease and injury using stem cell therapies.

03/25/2001

http://creationsafaris.com/crev03.htm

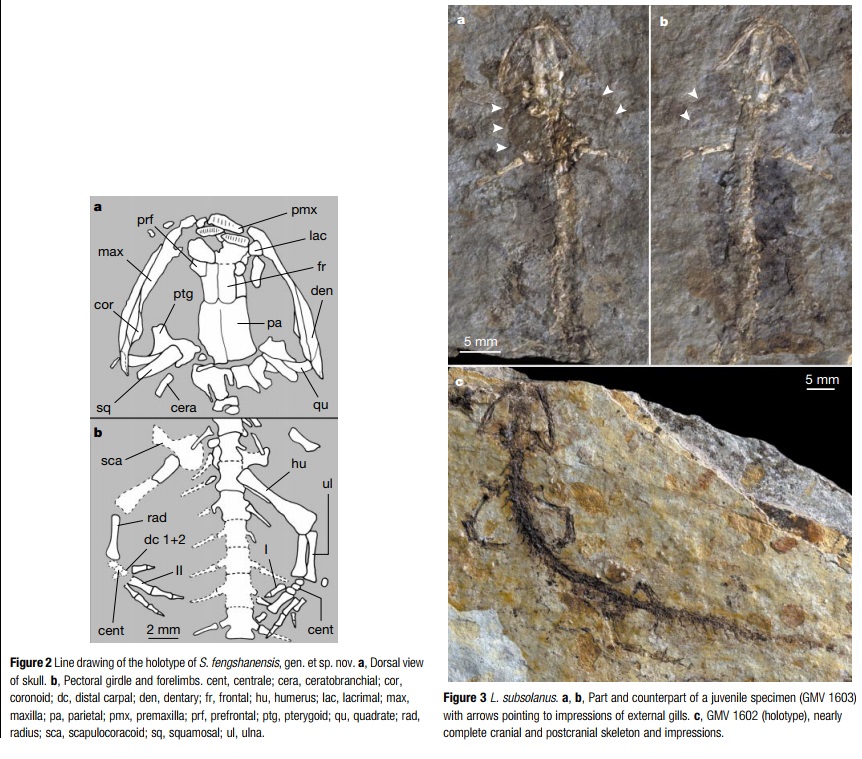

A new treasure-trove of exquisitely detailed salamander fossils has been found in China, according to Science Now. Evolutionists claim they are 150 million years old, the oldest salamander skeletons known, yet indistinguishable from modern species.

The evolution proponents immediately jump for joy at the prospect of studying salamander evolution here, but fail to ponder the logical question that if evolution is such a pervasive agent of change, why are today’s salamanders virtually identical to their 150 million-year-old parents? The article mentions “possible salamander ancestors in the Paleozoic,” leaving room for storytelling. The article says the fossils are dead ringers for those alive today, but in the next sentence quotes a paleontologist calling them “very primitive.” This is the Darwinian mindset, feeling compelled to shoehorn things into an evolutionary sequence, whether they fit or not. Salamanders are not primitive! They are highly complex vertebrates with exquisite capabilities for respiration in water and on land. The fossil record in general shows abrupt appearance of complex life-forms, and often catastrophic burial. That pattern is exemplified right here with these salamanders.

Fossil Salamanders Show No Evolution 03/27/2003

http://creationsafaris.com/crev0303.htm

If the Chinese team that found 200 fossil salamanders in Mongolia have their dates right, there has been little or no evolution for over 160 million years. Writing in the March 27 issue of Nature, they say (emphasis added):

Despite its Bathonian [161 million year] age, the new cryptobranchid shows extraordinary morphological similarity to its living relatives. This similarity underscores the stasis within salamander anatomical evolution. Indeed, extant cryptobranchid salamanders can be regarded as living fossils whose structures have remained little changed for over 160 million years. Furthermore, the new material from China reveals that the early diversification of salamanders was well underway by the Middle Jurassic; several extant taxa including hynobiids and cryptobranchids had already appeared by that time. Notably, this ancient pattern of taxonomic diversification does not correlate to any great disparity in anatomical structure.

This discovery predates the earlier record for this type by 100 million years. The specimens about 7 inches long and are so well preserved even soft tissue impressions are clear and distinct. BBC News has a report and picture.

These kinds of reports are becoming so common that predictions of abrupt appearance and stasis should be the norm, not the exception. The authors provide no evidence of an ancestral form; both types do not show “any great disparity in anatomical structure,” and were clearly fully operational as salamanders when they were buried. All they can say is that if evolution had split the two groups apart, it had to have happened before the Middle Jurassic. That’s like saying if Santa Claus really came, he must have done it before 8:00 p.m., because the presents were already under the tree, completely wrapped. Amazingly, National Geographic titles their article, “China Ash Yields Salamander Evolution Secrets.” Read their whole write-up with bewilderment that anyone could spin this story into evidence for evolution. Evolution is supposed to be this all-encompassing, all-pervasive force of change, yet look ye here: salamanders, nearly indistinguishable from living ones, with no evolution for 160 million years. The same could be said for horseshoe crabs, coelacanth fish, ginkgo trees, Wollemi pines, tuatara lizards, and a host of other known living fossils. Either (1) evolution is a myth, or (2) their dating methods are wrong. Pick any two.

Salamanders are ‘living fossils’!

http://creation.com/salamanders-are-living-fossils

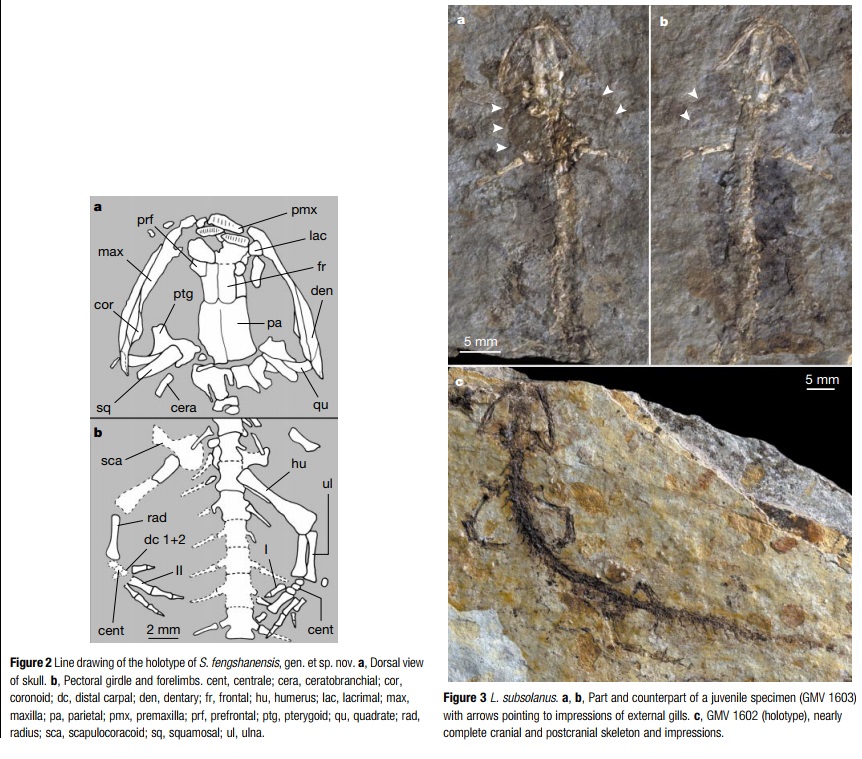

Late Jurassic salamanders from northern China

http://www.nature.com.sci-hub.bz/nature/journal/v410/n6828/full/410574a0.html

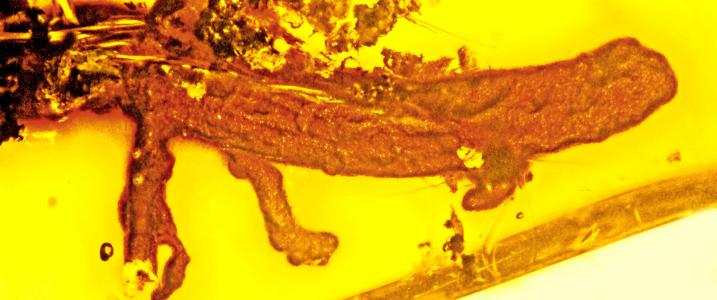

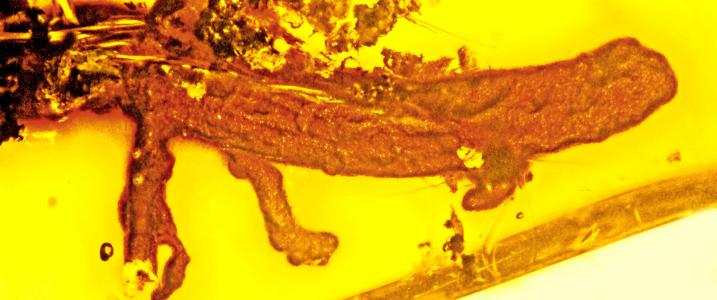

First-ever discovery of a salamander in amber sheds light on evolution of Caribbean islands

http://oregonstate.edu/ua/ncs/archives/2015/aug/first-ever-discovery-salamander-amber-sheds-light-evolution-caribbean-islands

More than 20 million years ago, a short struggle took place in what is now the Dominican Republic, resulting in one animal getting its leg bitten off by a predator just before it escaped. But in the confusion, it fell into a gooey resin deposit, to be fossilized and entombed forever in amber. The fossil record of that event has revealed something not known before – that salamanders once lived on an island in the Caribbean Sea. Today, they are nowhere to be found in the entire Caribbean area. The never-before-seen and now extinct species of salamander, named Palaeoplethodon hispaniolae by the authors of the paper, adds more clues to the ecological and geological history of the islands of the Caribbean. Findings about its brief life and traumatic end – it was just a baby – have been published in the journal Palaeodiversity, by researchers from Oregon State University and the University of California at Berkeley.

Salamanders, Order Caudata, together with frogs (Order Anura) and caecilians (Order Gymnophiona) (all clades), constitute the Class Amphibia. The number of salamander species is about 10% that of frogs, but they are three times more abundant than caecilians. Most taxonomies place salamanders in ten families: Ambystomatidae (1 genus, 32 species; North America), Amphiumidae (1 genus, 3 species; southeastern North America), Cryptobranchidae (2 genera, 3 species; eastern Asia, eastern North America), Dicamptodontidae (1 genus, 4 species; northwestern North America), Hynobiidae (9 or 10 genera, 52 species; Asia, entering eastern Europe), Plethodontidae (27 genera, 394 species; North, Middle, and South America, Korea, southern Europe), Proteidae (2 genera, 6 species; eastern North America, southern Europe), Rhyacotritonidae (1 genus, 4 species; northwestern North America), Salamandridae (20 or 21 genera, 81 species; Europe, Asia, North Africa, North America), Sirenidae (2 genera, 3 species; southeastern North America). The nearly 600 species of salamanders occur mainly in the Northern Hemisphere, but the Plethodontidae has successfully occupied the New World tropics, where nearly 40% of all salamander species are found. Several clades within Plethodontidae include the spelerpines (free-tongued species with larvae from eastern to central North America), desmognathines (eastern North American species with unique mouth-opening mechanisms), and New World tropical bolitoglossines (free-tongued species lacking larvae).

In the Old World a few members of the most widely distributed family, Salamandridae, reach the tropics in southern China and northern Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand. All but one of the families (Hynobiidae) live in North America, which has five endemic families (AmphibiaWeb 2009).

http://reasonandscience.heavenforum.org/t2603-salamanders-are-amazing

The Princeton Guide to Evolution, page 3:

Approximately 375 million years ago, a large and vaguely salamander-like creature plodded from its aquatic home and began the vertebrate invasion of land, setting forth the chain of evolutionary events that led to the birds that fill our skies, the beasts that walk our soil, me writing this chapter, and you reading it.

Ancient Amphibian: Debate Over Origin Of Frogs And Salamanders Settled With Discovery Of Missing Link

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/05/080521131541.htm

The examination and detailed description of the fossil, Gerobatrachus hottoni (meaning Hotton's elder frog), proves the previously disputed fact that some modern amphibians, frogs and salamanders evolved from one ancient amphibian group called temnospondyls.

Salamanders have huge genomes because they lose DNA slowly

http://www.sciguru.org/newsitem/15368/salamanders-have-huge-sized-genomes-because-they-did-not-shed-their-genes

Whereas the human genome is made up of about 3.2 billion base pairs, a salamander genome may contain as many as 120 billion base pairs. Salamanders have the largest genome sizes among four-footed animals (tetrapods) and, with the exception of lungfishes, among vertebrates as a whole.

Slow DNA Loss in the Gigantic Genomes of Salamanders

https://academic.oup.com/gbe/article/4/12/1340/608259/Slow-DNA-Loss-in-the-Gigantic-Genomes-of

Salamanders have the largest genome sizes among tetrapods and, with the exception of lungfishes, among vertebrates as a whole. Genome sizes across the 624 species of salamanders range from ∼14 Gb to ∼120 Gb

Genetic elements that drive regeneration uncovered

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/04/160406140405.htm

Salamanders and fish possess genes that can enable healing of damaged tissue and even regrowth of missing limbs. The key to regeneration lies not only in the genes, but in the DNA sequences that regulate expression of those genes in response to an injury. Researchers have discovered regulatory sequences that they call ’tissue regeneration enhancer elements’ or TREEs, which can turn on genes in injury sites.

Modulation of tissue repair by regeneration enhancer elements

http://sci-hub.cc/10.1038/nature17644

How some salamanders regrow their limbs

http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2016/06/how-some-salamanders-regrow-their-limbs

The ability to grow a new limb may seem like something straight out of science fiction, but new research shows exactly how animals like salamanders and zebrafish perform this stunning feat—and how humans may share the biological machinery that lets them do it. Scientists have long known of the regenerative powers of some species of fish and amphibians: To recreate a limb or fin lost to a hungry predator, they can regrow everything from bone to muscle to blood vessels with stem cells that form at the site of the injury. But just how they do it at the genetic level is a mystery. To figure out what might be happening, scientists amputated the appendages of two ray-finned fish—zebrafish and bichir—and a salamander known as the axolotl, all of which can regrow their legs and fins. They then compared RNA from the site of the amputation. They found 10 microRNAs—small pieces of RNA that regulate gene expression—that were the same in all three species. What’s more, they seemed to function in the same way, despite the structural difference between the axolotl (pictured above) and the fishes. The finding supports an existing idea that the three master limb-replacers last shared a common ancestor about 420 million years ago, and it suggests that the evolutionary process of growing limbs is saved over time, not developed independently in separate species, the researchers report today in PLOS ONE. What does this mean for humans? If these microRNAs can be programmed to work like they do in salamanders and fish, humans could enhance their ability to heal from serious injuries. But don’t expect to get Wolverine-like powers just yet—scientists say such modifications are still a long way off.

Deep-time evolution of regeneration and preaxial polarity in tetrapod limb development

http://www.nature.com.sci-hub.bz/nature/journal/v527/n7577/full/nature15397.html

Among extant tetrapods, salamanders are unique in showing a reversed preaxial polarity in patterning of the skeletal elements of the limbs, and in displaying the highest capacity for regeneration, including full limb and tail regeneration. These features are particularly striking as tetrapod limb development has otherwise been shown to be a highly conserved process. It remains elusive whether the capacity to regenerate limbs in salamanders is mechanistically and evolutionarily linked to the aberrant pattern of limb development; both are features classically regarded as unique to urodeles. New molecular data suggest that salamander-specific orphan genes play a central role in limb regeneration and may also be involved in the preaxial patterning during limb development. Here we show that preaxial polarity in limb development was present in various groups of temnospondyl amphibians of the Carboniferous and Permian periods, including the dissorophoids Apateon and Micromelerpeton, as well as the stereospondylomorph Sclerocephalus. Limb regeneration has also been reported in Micromelerpeton , demonstrating that both features were already present together in antecedents of modern salamanders 290 million years ago. Furthermore, data from lepospondyl ‘microsaurs’ on the amniote stem indicate that these taxa may have shown some capacity for limb regeneration and were capable of tail regeneration , including re-patterning of the caudal vertebral column that is otherwise only seen in salamander tail regeneration. The data from fossils suggest that salamander-like regeneration is an ancient feature of tetrapods that was subsequently lost at least once in the lineage leading to amniotes. Salamanders are the only modern tetrapods that retained regenerative capacities as well as preaxial polarity in limb development.

Salamander Offers Two Evolutionary Quandaries: Non-Homologous Development and an ORFan

https://evolutionnews.org/2017/01/salamander_offe/

The evolution and phylogeny of crown group salamanders is plagued by homoplasy. In fact, a large a number of highly derived anatomical characters, including body elongation, tail autonomy, and life history pathways, have been demonstrated or are debated to have evolved multiple times. The findings of unique (non-homologous) development patterns, and lineage-specific genes make no sense on evolution. And attempts to explain these findings according to evolution with clever, detailed hypotheses just cause more problems. If you try to build a house on a faulty foundation, it will just get worse. Evolution is a flawed theory, and the more we learn about biology, the more evident that becomes.

No Salamander Evolution Evidence, Past or Present

http://www.icr.org/article/no-salamander-evolution-evidence-past/

Study of salamanders in ponds demonstrates 'invisible finger of evolution'

https://phys.org/news/2013-05-salamanders-ponds-invisible-finger-evolution.html

Algae that live inside the cells of salamanders are the first known vertebrate endosymbionts

https://phys.org/news/2011-04-algae-cells-salamanders-vertebrate-endosymbionts.html

Gene Thieves: Female Salamanders Hijack DNA from Multiple Males

https://www.livescience.com/59639-salamanders-steal-genes.html

In the natural world, stealing is a necessary and frequent strategy for survival. Every animal group includes opportunists that snatch others' fresh kills, pilfer nesting materials or swipe prospective mates from distracted rivals.

But only one type of animal uses thievery at the genetic level for reproduction — an all-female lineage of salamanders in the Ambystoma genus, which contains dozens of species and is widespread across North America. These females mate with multiple males from other Ambystoma species and hijack copies of their partners' genomes, researchers discovered about a decade ago. However, scientists recently found that the salamanders weren't just stealing the males' genomes. They're incorporating genetic material from males across multiple species into their own genetic code and using all of them at the same time — a process that is otherwise unheard of in animals, researchers reported in a new study.

Algae Invaders Actually Benefit Their Salamander Hosts

http://www.icr.org/article/algae-invaders-actually-benefit-their/

Xeroxed lung gene helps salamanders breathe through their skin

http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2016/01/xeroxed-lung-gene-helps-salamanders-breathe-through-their-skin

Almost all land animals need lungs to survive. The world’s largest group of salamanders is a rare exception. Now, researchers know how these amphibians came to breathe through their skin instead. A copy of a key lung gene shifted where it is active, rendering skin capable of efficient gas exchange, they reported here this week at the annual meeting of the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology. The loss of lungs represents major evolutionary change, one expected to limit the size, lifestyle, and whereabouts of any species. But the 448 species of a family of salamanders called plethodontids must not have gotten that message, as they roam across the Western Hemisphere, South Korea, and Italy; range from 25 millimeters to 27 centimeters long; and call burrows to tree tops home. So evolutionary developmental biologists tracked embryonic development of one of these species, the dusky salamander (Desmognathus fuscus), and discovered that although lungs do start to form, they never fully develop. Instead, this species produces extra blood vessels to the skin. Studies of gene activity in this and other vertebrates also revealed that there is a key gene in the vertebrate lung that exists in two copies in salamanders. That gene is active just in the lungs of lunged salamanders, but in lungless species is active in the skin, mouth, and throat as well. It codes for a protein that helps membranes be more receptive to gas exchange, and its presence in the skin and mouth helps explain why some salamanders don’t need lungs at all. Called a surfactant protein, this newly discovered protein may prove useful for treating breathing problems in people, the researchers note.

Mexican salamander helps uncover mysteries of stem cells and evolution

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/07/100711205804.htm

Scientists have been using a Mexican aquatic salamander called an axolotl to study the evolution and genetics of stem cells -- research that supports the development of regenerative medicine to treat the consequences of disease and injury using stem cell therapies.

03/25/2001

http://creationsafaris.com/crev03.htm

A new treasure-trove of exquisitely detailed salamander fossils has been found in China, according to Science Now. Evolutionists claim they are 150 million years old, the oldest salamander skeletons known, yet indistinguishable from modern species.

The evolution proponents immediately jump for joy at the prospect of studying salamander evolution here, but fail to ponder the logical question that if evolution is such a pervasive agent of change, why are today’s salamanders virtually identical to their 150 million-year-old parents? The article mentions “possible salamander ancestors in the Paleozoic,” leaving room for storytelling. The article says the fossils are dead ringers for those alive today, but in the next sentence quotes a paleontologist calling them “very primitive.” This is the Darwinian mindset, feeling compelled to shoehorn things into an evolutionary sequence, whether they fit or not. Salamanders are not primitive! They are highly complex vertebrates with exquisite capabilities for respiration in water and on land. The fossil record in general shows abrupt appearance of complex life-forms, and often catastrophic burial. That pattern is exemplified right here with these salamanders.

Fossil Salamanders Show No Evolution 03/27/2003

http://creationsafaris.com/crev0303.htm

If the Chinese team that found 200 fossil salamanders in Mongolia have their dates right, there has been little or no evolution for over 160 million years. Writing in the March 27 issue of Nature, they say (emphasis added):

Despite its Bathonian [161 million year] age, the new cryptobranchid shows extraordinary morphological similarity to its living relatives. This similarity underscores the stasis within salamander anatomical evolution. Indeed, extant cryptobranchid salamanders can be regarded as living fossils whose structures have remained little changed for over 160 million years. Furthermore, the new material from China reveals that the early diversification of salamanders was well underway by the Middle Jurassic; several extant taxa including hynobiids and cryptobranchids had already appeared by that time. Notably, this ancient pattern of taxonomic diversification does not correlate to any great disparity in anatomical structure.

This discovery predates the earlier record for this type by 100 million years. The specimens about 7 inches long and are so well preserved even soft tissue impressions are clear and distinct. BBC News has a report and picture.

These kinds of reports are becoming so common that predictions of abrupt appearance and stasis should be the norm, not the exception. The authors provide no evidence of an ancestral form; both types do not show “any great disparity in anatomical structure,” and were clearly fully operational as salamanders when they were buried. All they can say is that if evolution had split the two groups apart, it had to have happened before the Middle Jurassic. That’s like saying if Santa Claus really came, he must have done it before 8:00 p.m., because the presents were already under the tree, completely wrapped. Amazingly, National Geographic titles their article, “China Ash Yields Salamander Evolution Secrets.” Read their whole write-up with bewilderment that anyone could spin this story into evidence for evolution. Evolution is supposed to be this all-encompassing, all-pervasive force of change, yet look ye here: salamanders, nearly indistinguishable from living ones, with no evolution for 160 million years. The same could be said for horseshoe crabs, coelacanth fish, ginkgo trees, Wollemi pines, tuatara lizards, and a host of other known living fossils. Either (1) evolution is a myth, or (2) their dating methods are wrong. Pick any two.

Salamanders are ‘living fossils’!

http://creation.com/salamanders-are-living-fossils

Late Jurassic salamanders from northern China

http://www.nature.com.sci-hub.bz/nature/journal/v410/n6828/full/410574a0.html

First-ever discovery of a salamander in amber sheds light on evolution of Caribbean islands

http://oregonstate.edu/ua/ncs/archives/2015/aug/first-ever-discovery-salamander-amber-sheds-light-evolution-caribbean-islands

More than 20 million years ago, a short struggle took place in what is now the Dominican Republic, resulting in one animal getting its leg bitten off by a predator just before it escaped. But in the confusion, it fell into a gooey resin deposit, to be fossilized and entombed forever in amber. The fossil record of that event has revealed something not known before – that salamanders once lived on an island in the Caribbean Sea. Today, they are nowhere to be found in the entire Caribbean area. The never-before-seen and now extinct species of salamander, named Palaeoplethodon hispaniolae by the authors of the paper, adds more clues to the ecological and geological history of the islands of the Caribbean. Findings about its brief life and traumatic end – it was just a baby – have been published in the journal Palaeodiversity, by researchers from Oregon State University and the University of California at Berkeley.

Salamanders, Order Caudata, together with frogs (Order Anura) and caecilians (Order Gymnophiona) (all clades), constitute the Class Amphibia. The number of salamander species is about 10% that of frogs, but they are three times more abundant than caecilians. Most taxonomies place salamanders in ten families: Ambystomatidae (1 genus, 32 species; North America), Amphiumidae (1 genus, 3 species; southeastern North America), Cryptobranchidae (2 genera, 3 species; eastern Asia, eastern North America), Dicamptodontidae (1 genus, 4 species; northwestern North America), Hynobiidae (9 or 10 genera, 52 species; Asia, entering eastern Europe), Plethodontidae (27 genera, 394 species; North, Middle, and South America, Korea, southern Europe), Proteidae (2 genera, 6 species; eastern North America, southern Europe), Rhyacotritonidae (1 genus, 4 species; northwestern North America), Salamandridae (20 or 21 genera, 81 species; Europe, Asia, North Africa, North America), Sirenidae (2 genera, 3 species; southeastern North America). The nearly 600 species of salamanders occur mainly in the Northern Hemisphere, but the Plethodontidae has successfully occupied the New World tropics, where nearly 40% of all salamander species are found. Several clades within Plethodontidae include the spelerpines (free-tongued species with larvae from eastern to central North America), desmognathines (eastern North American species with unique mouth-opening mechanisms), and New World tropical bolitoglossines (free-tongued species lacking larvae).

In the Old World a few members of the most widely distributed family, Salamandridae, reach the tropics in southern China and northern Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand. All but one of the families (Hynobiidae) live in North America, which has five endemic families (AmphibiaWeb 2009).

Last edited by Admin on Sat Aug 26, 2017 12:23 pm; edited 18 times in total