Atheism: Debates, Evidence, and Philosophical Perspectives

Atheist Professor Graham Oppi Gives REAL Definition of Atheism (very based): "Atheism is the view that there are no Gods" 1

Negative atheism, also called weak atheism and soft atheism is any type of atheism where a person does not believe in the existence of any deities but does not explicitly assert that there are none. Link

Positive atheism, also called strong atheism and hard atheism is the form of atheism that additionally asserts that no deities exist

Agnosticism is the view that the existence of God, of the divine or the supernatural, is unknown or unknowable. An agnostic can also hold neither of two opposing positions on a topic. Link

Skepticism (American English) or skepticism is generally any questioning attitude or doubt towards one or more items of putative knowledge or belief. Link

Freethought (or "free thought")is a philosophical viewpoint that holds that positions regarding truth should be formed based on logic, reason, and empiricism, rather than authority, tradition, revelation, or dogma Link

Anti-Theism The view that theism, religion, and belief in God must be opposed. The individual believes that religious belief is both dangerous and harmful. Anti-theists are often Strong Atheists. Link

Apatheism The individual lives as if there are no gods and explains natural phenomena without invoking the divine. Typically the individual doesn’t care whether or not God exists. Link

Explicit Atheism The individual makes a positive assertion regarding their lack of belief in God and/or gods. Implicit Atheism The absence of belief in one or more gods, without a conscious rejection of it. Link

There are further categorizations and nuances within atheism related to various philosophical, ethical, and epistemological stances. These categorizations often intersect with broader worldviews and can provide more specific insights into an individual's perspective on religion, deities, and the supernatural.

Practical Atheism: This stance involves living one's life without any reference to gods or deities, regardless of one's theoretical belief in them. Practical atheists may not spend much time considering the existence of deities because it has no practical impact on their daily lives.

Theological Noncognitivism: This is the position that religious language, particularly discourse about God or gods, is not cognitively meaningful. It suggests that statements like "God exists" do not express propositions that can be true or false in any meaningful sense. This can lead to a form of atheism because it denies the coherence of theistic claims.

Ignosticism: Similar to theological noncognitivism, ignosticism is the view that a coherent definition of God must be presented before the question of the existence of God can be meaningfully discussed. If the definition is unfalsifiable, the ignostic takes the theological noncognitivist stance that the question is meaningless.

Secular Humanism: While not strictly a form of atheism, secular humanism is a worldview and ethical system that emphasizes human well-being, ethical values, and natural explanations for phenomena without recourse to the supernatural. Many secular humanists are atheists, as they do not include the divine in their ethical or philosophical considerations.

Atheistic Religion: Some religions or belief systems, such as certain forms of Buddhism and Jainism, do not include a creator god in their doctrine, which makes them atheistic in a sense. However, followers may still engage in religious practices, and rituals, and hold spiritual beliefs.

Atheism and Spirituality: Some atheists identify as spiritual, finding awe and wonder in the natural world, humanity, and the universe without attributing these feelings to a deity. This form of atheism recognizes a sense of connectedness or transcendence that does not rely on traditional notions of theism.

Post-Theism: This stance posits that humanity is in a post-religious phase where the concept of god is unnecessary for explaining natural phenomena or for providing ethical guidelines. It sees theism as a historical phase that humanity has evolved beyond.

These categorizations show the diversity within atheism and related stances, highlighting that disbelief in deities can come with a variety of philosophical underpinnings and implications. Individuals may identify with multiple categories simultaneously, and these labels can often overlap or be used in combination to describe one's specific viewpoint.

Claim: Atheism is just about the rejection of the claim of the existence of God because there is no evidence for his existence. I am just not convinced about your arguments of God's existence.

Reply: The discussion around atheism often becomes tedious when individuals presume the need to educate others on its principles as if this would be the first encounter with such explanations. Atheists, like everyone else trying to make sense of the world, are not exempt from the burden of proof. Atheists believe that the significant questions of life can be addressed without resorting to the notion of a divine supernatural entity. In contrast, theists observe that naturalistic explanations often fall short, suggesting that the idea of an intelligent, transcendent force provides a more convincing explanation. In such instances, theists consider it logically sound to deduce a supernatural origin.

Atheism, in its essence, is defined by the rejection of a personal god. However, the spectrum of atheistic belief is broad, encompassing deists who accept a non-interventionist creator, agnostics who remain uncertain about the divine, materialists who deny anything beyond the physical, and even those who subscribe to panpsychism, believing in the inherent intelligence of the cosmos. Therefore, "atheist" serves as a catch-all term for anyone who does not identify as a theist.

Does atheism just as a ‘lack of belief’ make any sense?

Claim: Atheism is not a religion or philosophy. It is simply a lack of faith or belief in God(s).

Answer: The assertion "I lack belief in a god" is a stance frequently adopted by atheists, likening their skepticism about God to disbelief in fantastical notions such as invisible pink unicorns. They claim to maintain a neutral stance, devoid of any belief or disbelief regarding divinity, treating the subject as inconsequential. However, this perspective overlooks a critical aspect of human cognition: once introduced to an idea, neutrality is no longer viable. Exposure to a new concept necessitates some form of cognitive response, whether it's outright dismissal, contemplation of its validity, acceptance, rejection, or any stance in between. The claim of returning to a pre-exposure state of non-belief, defined as an absence of cognitive engagement, is untenable. Consider a child unaware of the concept of invisible pink unicorns. Upon learning of this concept later in life, the child must inherently form an opinion, ranging from belief to skepticism, amusement, indecision, or deferred judgment. The exposure compels the child to adopt a stance, moving beyond the initial state of unawareness. Some might argue that deferring judgment aligns with atheistic views on non-belief. However, choosing to withhold judgment following exposure to an idea is a form of engagement, differing from a lack of awareness. This stance, akin to agnosticism, reflects an open-mindedness to new information, acknowledging the possibility of the concept's existence pending further evidence. This is distinct from atheism, which is often characterized by a definitive lack of belief. To illustrate, consider the hypothetical suggestion of an ice cream factory on Jupiter. Upon hearing this, one might react with skepticism, amusement, curiosity for evidence, or whimsical musings about interplanetary ice cream. Such a notion is instinctively categorized as implausible, demonstrating that exposure to an idea inevitably leads to some form of judgment, thereby challenging the possibility of maintaining a true state of non-belief.

The argument that one can simply "lack belief" in a deity, as often claimed by atheists, overlooks the inherent human tendency to evaluate and categorize ideas from full endorsement to outright dismissal. This natural inclination challenges the notion of passive non-belief. Consider the analogy of animals and their apparent absence of belief in deities. For instance, my bulldog Bobby, a remarkably intelligent and engaging pet, demonstrated no understanding or belief in the concept of God. This lack of belief, however, doesn't classify him or other non-sentient entities like infants, plants, or inanimate objects as atheists. Atheism, in this context, seems applicable only to sentient beings capable of contemplating such concepts. Yet, the broader assertion by some atheists that their stance is merely a "lack of belief" seems to sidestep a more profound engagement with the philosophical and theological discussions surrounding atheism. This stance can be seen as a way to avoid the scrutiny and critique that comes with holding a more defined position. The growing discourse and critique from various religious and philosophical perspectives are challenging atheistic positions more rigorously, prompting a more defensive posture from the atheist community. This discourse is not just an intellectual exercise but a reflection of a deeper search for truth, with significant implications for the validity and sustainability of atheistic beliefs in the face of growing scrutiny and debate.

The assertion that atheism equates to a lack of concern is contradicted by the actions of many vocal atheists, who actively engage in discussions and debates about their disbelief. This suggests that atheism, for some, goes beyond the mere absence of belief in deities to a more defined stance, often articulated as the belief in the nonexistence of God. This active engagement raises questions about the depth and substance of one's identity if it primarily revolves around a disbelief in something. Weak atheists center on critiquing the beliefs of others rather than proposing a constructive worldview of their own. This comparison is drawn to highlight an inconsistency: while one might not actively campaign against belief in UFOs due to personal disbelief, some atheists adopt a more proactive stance in expressing their disbelief in God. The conversation around atheism often blurs the lines between weak atheism, agnosticism, and strong atheism, with various strategies employed to argue against theistic beliefs. Some atheists might use evasive tactics, such as claiming ignorance or deferring to science, as a means to sidestep deeper philosophical discussions about naturalism and the existence of a deity. This can come across as intellectual dishonesty, where the refusal to believe in a deity is seen not as a neutral lack of belief but as a deliberate choice influenced by personal will. The debate extends to the nature of evidence and belief. When atheists assert the absence of proof for a deity's existence, it raises the question of whether their stance on the natural world is similarly based on faith, given the lack of definitive proof that the natural world is all there is. This challenges the notion that atheism is a purely passive absence of belief, instead, it is an active choice to reject theistic evidence, which is often dismissed out of a reluctance to engage with the possibility of a deity's existence.

While asserting rational and open-minded approaches, some atheists are being closed off to any evidence or reasoning that might evidence the existence of God, which is a form of willful ignorance rather than true rational skepticism. Furthermore, the discussion often involves atheists making accusations of theists misunderstanding or oversimplifying concepts like atheism and evolution, which are evasive tactics rather than substantive arguments.

In his essay "Herding Cats: Why atheism will lose," Francois Tremblay suggests that atheism's credibility is undermined if atheists cannot substantiate their fundamental beliefs about reality and cognition, likening unfounded atheism to a "paper tiger." A meaningful stance on atheism requires intellectual engagement and the willingness to substantiate disbelief with reasoned arguments.

Why the “I Just Believe in One Less God than You” Argument Does Not Work

Argument: “I contend we are both atheists, I just believe in one less god than you do. When you understand why you dismiss all the other possible gods, you will understand why I dismiss yours.” Another way to phrase it: “I don’t have to take the time to reject Christ any more than you have to take the time to reject all the millions of gods that are out there. It just happens by default. The justification for my atheism is the same as yours concerning your rejection of all the other possible gods.” And another: "I don’t believe in Yahweh. I don’t believe in Hercules either."

Response: In addressing the contention that the distinction between atheists and theists is merely the disbelief in one additional deity, it's essential to delve into the nuanced nature of divine belief. The monotheistic concept of God stands apart from the pantheon of polytheistic gods not merely in number but in the very essence of divinity. Within the monotheistic framework, God is not envisioned as another entity within the cosmos but as the foundational underpinning of all reality, the very bedrock upon which existence itself is contingent. This conceptualization transcends the realm of superhuman beings governing specific domains, characteristic of polytheistic traditions, and ventures into a philosophical domain where God is the necessary "unmoved mover" or "first cause," a principle without parallel in the realm of polytheism.

The argument often overlooks the epistemological distinctions between innate knowledge and constructed beliefs. Monotheistic traditions posit an inherent, intuitive knowledge of a creator, discernible through the natural world's complexity and order, contrasting sharply with the culturally constructed deities of polytheism, which often fulfill explanatory or societal roles. Moreover, the dismissal of all deities based on the rejection of some neglects the independent lines of evidence and reasoning that might underpin the belief in a specific monotheistic God, such as cosmological, teleological, or moral considerations.

Asserting that atheism and theism differ only in the rejection of one additional god implies a false equivalence, treating all concepts of divinity as interchangeable and dismissible on identical grounds. This perspective fails to engage with the unique arguments and experiences that support a monotheistic belief, which demands consideration on its terms. Such a stance also involves a category error, erroneously equating the monotheistic God, not as a being within the universe but as the very ground of being and existence, with gods that, however powerful, exist within the universe's confines.

Furthermore, the historical and cultural evolution of religious beliefs from polytheism to monotheism in various traditions often reflected deeper philosophical and theological exploration rather than a mere reduction in the number of deities. The diversity of religious expressions and the multiplicity of gods across cultures might better be understood as humanity's manifold attempts to comprehend and articulate the divine, rather than evidence against the existence of a singular, ultimate deity.

In summary, the debate transcends a simplistic comparison between atheism and theism based on the number of gods rejected. It invites a deeper exploration into the nature of belief, the philosophical underpinnings of monotheism, and the logical and epistemological considerations that distinguish a grounded belief in a singular, foundational deity from the dismissal of an array of mythological figures.

The Burden of Proof: Is It Solely the Responsibility of Theists to Provide It?

The discourse around the burden of proof in debates between theists and atheists is often charged and polarized. In discussions about the existence of God, theists are typically asked to provide evidence for God's existence. This expectation is based on the philosophical principle that the one making an affirmative claim carries the burden to substantiate it. However, atheists, too, should bear a burden of proof, particularly when they posit naturalistic explanations for phenomena traditionally attributed to divine intervention or creation. If atheists challenge theistic views, they should also provide positive evidence for their naturalistic viewpoints, rather than solely critiquing theistic claims. A more constructive approach would involve articulating and defending a naturalistic view of the universe that explains the existence of the universe, life, biodiversity, and consciousness. Theists are not the only ones who have the burden of proof. Anyone making claims about the nature of reality, whether theistic or naturalistic, should be prepared to support their claims with evidence. This calls for a more balanced discourse where both sides are expected to present well-reasoned, evidence-based arguments for their respective worldviews, be they theistic, atheistic, or otherwise.

Is there a dispute between Science and Religion?

The most profound ideological conflict isn't between science and religion, which often find ways to coexist harmoniously, but rather between the philosophical perspectives of naturalism and theism. These viewpoints offer fundamentally different interpretations of reality and existence. Like abstract concepts such as numbers and logical principles, metaphysics transcends sensory experience, placing the debate between naturalism and theism firmly within the philosophical domain. Metaphysical naturalism posits that the entirety of reality is confined to the physical matter and energy within space-time, dismissing any existence beyond the natural world. This perspective inherently rejects supernatural entities or phenomena, such as deities, souls, or other spiritual beings, and negates the notion of an overarching purpose or design in the universe, as it denies the existence of any conscious designer. Conversely, theism presents the universe as the creation of a Supreme Being who not only initiated its existence but continues to sustain it, existing beyond the physical boundaries of the universe. By their very nature, these two ideologies are in direct opposition to one another. In the discourse surrounding the origins and complexity of life and the universe, Intelligent Design has been positioned as an emerging scientific theory on the cusp of gaining acceptance within the scientific community. A scientific theory is defined as a well-substantiated explanation for the natural world, one that is formulated based on rigorous testing, observation, and analysis in line with the scientific method. This process includes the critical examination of hypotheses through empirical study and the validation of findings according to established scientific standards.

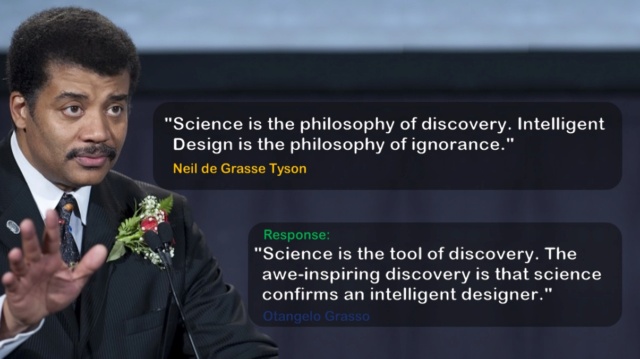

Neil deGrasse Tyson: "Science is the philosophy of discovery. Intelligent Design is the philosophy of ignorance. " 2

Response: "Science is the tool of discovery. The awe-inspiring discovery is that science confirms an intelligent designer. "

Science, in its essence, is a remarkable tool of discovery that continuously unveils previously unfathomable complexities and the majestic order of the universe. It's a journey through which humanity explores the vastness of space, the minutiae of cells, and the enigmatic laws of physics. This journey of discovery, far from distancing us from the notion of an intelligent designer, brings us closer to the awe-inspiring realization that the universe operates with precision and harmony that evidence a purposeful and intentional setup. Either in the quantum realms or farther in the cosmic expanse, we encounter patterns, laws, and a level of complexity that borders on the poetic. The constants and equations that govern the universe, the fine-tuning necessary for life to exist, and the beauty found in the natural world from the spirals of galaxies to the DNA's double helix structure, all evoke a sense of wonder and imply a designed instantiation. Moreover, the capacity for humans to appreciate beauty, pursue truth, and ponder their existence in the universe suggests a dimension of reality beyond mere survival and reproduction. These pursuits, while not tangible or quantifiable in the same way physical phenomena point to a depth of human experience that material explanations alone do not fully encompass. In this context, the idea of an intelligent designer is not necessarily at odds with the scientific endeavor but can be seen as a perspective that enriches our understanding of the universe. It invites us to consider not just how things are but why they might be, encouraging a holistic view of existence that marries the empirical with the existential. Thus, the unfolding revelations of science, rather than diminishing the possibility of an intelligent designer, amplify our sense of wonder and appreciation for the complexity and beauty of the world around us, pointing towards a greater purpose and design behind the cosmos.

Strong atheism is a faith-based worldview

Communal Gatherings: Atheists have formed communities and congregations that mirror the social and communal aspects of religious worship. Examples include "godless churches" and secular assemblies where individuals gather, not to worship deities, but to enjoy a sense of community, discuss ethical and philosophical issues, and support each other in their shared disbelief.

Foundational Texts: While not revered as divine scripture, works such as "The Atheist's Bible" serve as compilations of thoughts, arguments, and reflections that provide a foundation for atheist viewpoints, much like religious texts do for believers. These texts offer insights, moral philosophies, and reflections on the nature of the universe without appealing to a higher power.

Philosophical Frameworks: Atheism, particularly in its strong or "positive" form, which asserts the non-existence of gods, often relies on systematic philosophical arguments. Texts that outline atheism's reasoning against theological concepts provide a structured ideological framework that parallels the doctrinal treatises found in religious traditions.

Evangelism: Although atheism inherently lacks the divine mandate that often drives religious proselytization, some atheists actively engage in spreading their disbelief in gods, critiquing religious beliefs, and advocating for secularism. This "evangelical" aspect, where individuals are passionate about sharing and defending their atheistic views, resembles the missionary zeal found in many religions.

Prominent Figures: Just as religions have their revered leaders, prophets, or popes, atheism has its notable figures who are highly respected, influential, and often looked up to for guidance and inspiration. These individuals, through their writings, speeches, and debates, shape the atheistic discourse, much like religious leaders shape the faith and practices of their followers.

The perspective often associated with atheism, although not universally held or acknowledged by all who identify as atheists, implies a set of understandings about the universe that do not necessitate a divine creator. This worldview would suggest:

1. The existence and functionality of the natural world do not require a supernatural creator.

2. The complexity and order observed in nature arise naturally by unguided means, without the need for an intelligent designer.

3. The universe could have originated from natural phenomena, without the intervention of a divine force, or it might be part of an eternal cosmos.

4. The laws governing the physical universe emerge from its inherent properties, rather than being decreed by a higher power.

5. The apparent fine-tuning of universal constants and conditions could be a result of natural processes or multiple universes, rather than the actions of a purposeful designer.

6. Life and its origin can be explained through natural, chemical, and biochemical processes without invoking a supernatural life-giver.

7. The emergence of complex information, such as genetic codes, can be accounted for by chemical selection and/or eventually other evolutionary mechanisms.

8. Biological structures and systems can develop through evolutionary processes without the need for a divine architect.

9. The diversity of life on Earth can be understood through the theory of evolution, which explains how natural selection and genetic variation lead to speciation.

10. Consciousness and moral values can be seen as emergent properties of complex brain functions, not bestowed by a divine entity.

11. Meaning and purpose in life can be derived from personal experiences, relationships, and achievements, rather than being assigned by a higher power.

12. The concept of an afterlife is not necessary to give life significance or to understand human consciousness.

13. The lack of empirical evidence for deities is viewed not as a dismissal of the possibility but as a basis for focusing on the natural and observable world.

The Biblical Perspective on Atheism

The biblical perspective on atheism is deeply intertwined with its broader theological and moral teachings. Central to this perspective is the assertion found in Psalm 14:1, which declares, "The fool says in his heart, 'There is no God.'" This statement encapsulates the biblical stance that denying God's existence is not only mistaken but also a reflection of folly and moral corruption. From the outset, the Bible affirms the existence of God as a fundamental truth, beginning with the emphatic declaration in Genesis 1:1, "In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth." This foundational assertion sets the stage for understanding the biblical view of reality, one that is inherently theistic and sees God's creative power as evident in the world. The Bible articulates that the evidence of God's existence is manifest in the natural world, a principle echoed in Romans 1:20. This passage argues that God's "invisible qualities" are clearly perceived in the created order, rendering disbelief in God as indefensible and without excuse. Such a perspective implies that atheism is not a conclusion arrived at through impartial reasoning but is influenced by a predisposition toward unrighteousness and a rejection of divine authority. Ephesians 4:18 and Revelation 21:8 extend this argument, suggesting that atheism and other forms of unbelief are symptomatic of a deeper spiritual and moral estrangement from God. This estrangement is characterized by ignorance, hardness of heart, and a proclivity toward behaviors that are antithetical to God's moral law. The biblical narrative also posits that the natural world, in all its diversity and complexity, inherently points to a creator. This is illustrated in Job 12:7-9, where the harmony and order of the natural world are presented as testimonies to God's handiwork. Even the demons, as mentioned in James 2:19, acknowledge God's existence, further underscoring the irrationality of atheism from a biblical standpoint. The Bible presents atheism not merely as an intellectual position but as one rooted in moral and spiritual rebellion against God. It challenges the coherence of atheism by highlighting the evident design and purpose in creation, which testify to a Creator. The biblical critique of atheism extends beyond the mere denial of God's existence to address the underlying spiritual condition that fosters such disbelief. In doing so, the Bible shifts the focus from the question of God's existence to the nature of one's relationship with the true God, emphasizing the importance of knowing and worshiping God as revealed in the scriptures and through Jesus Christ.

Understanding the outspokenness of Atheists

The fervor with which some atheists and agnostics engage in discussions about faith and theism can be perplexing. This passion for promoting atheistic or agnostic viewpoints often seems aimed more at deconstructing the beliefs of others rather than constructing a positive framework for their own worldview. This approach focuses on the negation of faith rather than contributing constructively to personal or societal well-being, leading to a perception of atheism as embracing a void rather than offering an enriching alternative. Why do individuals who profess uncertainty or disbelief in theistic explanations invest significant energy in debating those who are content and fulfilled by their faith? The insistence on discussing the lack of evidence for deities or the origins of the universe, particularly when their stance is one of admitted ignorance on these ultimate questions, is counterintuitive. It raises questions about the motivation behind such engagements and whether the goal is to genuinely seek truth together or simply to undermine the convictions of others. The comparison between a fulfilled, content theist and an atheist engaging in such debates might resemble a juxtaposition between satisfaction and dissatisfaction. From this perspective, atheistic engagement is not a pursuit of shared understanding or enlightenment but an attempt to project one's own uncertainties or skepticism onto others. This approach focused more on dismantling rather than building, is not appealing or constructive to those who find solace and meaning in their faith. For those who hold theistic beliefs, especially those who find in them a deep sense of purpose and direction, the proposition to adopt a viewpoint characterized by doubt and uncertainty is unattractive. The inclination to engage with arguments that appear to offer nothing more than skepticism is understandably low, as such interactions can feel unproductive or even demeaning to one's deeply held convictions. The challenge then becomes one of dialogue and understanding. How can individuals with divergent views on theism and atheism engage in meaningful conversations that respect the integrity of each perspective? Is it possible to explore these profound questions of existence in a way that enriches rather than diminishes? For productive discourse to occur, there must be a mutual willingness to listen, understand, and appreciate the value and sincerity of each other's viewpoints, even if agreement is not reached. This requires moving beyond mere criticism and towards a more constructive exploration of the diverse ways humans seek meaning, purpose, and understanding.

The Skeptical Worldview and the Challenge of Origins of Our Physical Existence

Most skeptics pride themselves on their intellectual abilities and believe they hold no unsubstantiated beliefs. However, modern science has shown that everyone has beliefs, as this is how our brains function. Although we'd like to think our beliefs stem from evidence and logic, this is often not the case. In fact, we become emotionally attached to our worldviews, making significant worldview changes rare occurrences.

Principles of the Skeptical Worldview

1. All beliefs should be based on observational evidence. Unlike theists who partially base beliefs on religious texts, skeptics must rely entirely on physical evidence.

2. Skeptics must be logically consistent at all times. A skeptic cannot believe something contradicted by observational evidence.

3. Most skeptical atheists believe all phenomena have naturalistic causes, based on observing cause and effect in our world, with rare exceptions, if any.

However, insisting that supernatural events never occur is itself an unsubstantiated belief that can never be fully confirmed. To be truly open-minded, one must recognize the possibility that supernatural events do occur, even if rarely. Let's examine a major problem with the skeptical worldview: the origin of the universe. Before the 20th century, atheists assumed the universe was eternal. However, Einstein's theory of relativity and early observational evidence indicated the universe is expanding. Extrapolating backward revealed our universe had most likely a beginning, leading to the widely accepted Big Bang theory.

Attempts to circumvent a universe beginning have met observational difficulties. The oscillating universe theory was disproven by the insufficient matter in the universe and the inevitability of a "Big Crunch" instead of another Big Bang. So we've come to realize the universe began some finite time ago. Atheists face a dilemma, as the principle that everything that begins to exist must have a cause has never been refuted or overcome. Logic requires admitting the universe had a cause. Most atheists claim this cause was a natural phenomenon, or that we simply don't know yet what that cause might have been. Thus, any atheist definitively denying God's possible existence violates their own principle of basing beliefs on observational evidence. The problem worsens, as the physical laws allowing for life and matter's existence fall within narrow ranges, suggesting design. If true, the observational evidence actually leans toward God's existence, contradicting strong atheism. The prospect of finding a naturalistic cause for the universe's origin is bleak, as the laws of physics indicate we can never escape our universe to investigate its cause.

Strong atheists often employ a variety of scientific hypotheses to explain the origins and nature of the universe, life, and consciousness without recourse to a divine creator. These explanations span from the cosmological to the biological, attempting to provide a comprehensive naturalistic account of reality.

Multiverses: This hypothesis suggests that our universe is just one of many universes, potentially with varying physical constants and laws. The existence of a multiverse could provide a naturalistic explanation for the fine-tuning of the physical constants in our universe, which some argue is necessary for life. In a multiverse, it's statistically probable that at least one universe would have the right conditions for life.

Steady-State Universe: This now largely outdated model proposed that the universe is eternal and unchanging on a large scale, with matter continuously created to keep the density constant despite expansion. It was an alternative to the Big Bang theory but has fallen out of favor due to observational evidence supporting the Big Bang.

Oscillating Universes: This hypothesis posits that the universe undergoes infinite cycles of expansion and contraction, commonly referred to as "Big Bang" and "Big Crunch" phases. Each cycle is thought to renew the universe, potentially explaining its existence without a divine cause.

Virtual Particles: In quantum field theory, virtual particles spontaneously appear and disappear in a vacuum due to quantum fluctuations. Some atheists suggest that the universe could have arisen from such fluctuations, with virtual particles contributing to the energy density of the vacuum, possibly leading to the Big Bang.

Big Bang Theory: This widely accepted cosmological model describes the universe's expansion from an extremely hot, dense initial state. While it doesn't provide a complete explanation for the universe's initial conditions, it offers a detailed account of its development over 13.8 billion years, supported by extensive observational evidence.

Accretion Theory In the context of planetary formation, accretion theory describes how planets form from the dust and gas surrounding a new star. This naturalistic explanation accounts for the diversity and arrangement of planets in our solar system without invoking supernatural intervention.

Abiogenesis: This hypothesis seeks to explain the origin of life from non-living matter. Various models suggest that life began through simple organic compounds forming in Earth's early environment, eventually leading to more complex structures capable of replication and evolution.

Common Ancestry: Central to the theory of evolution, common ancestry posits that all life on Earth shares a common origin. Supported by genetic, fossil, and morphological evidence, this concept explains the diversity of life through natural selection and adaptation to different environments.

Evolution: The theory of evolution by natural selection, first articulated by Charles Darwin, explains the diversity of life as a result of genetic variation and environmental pressures. It's a cornerstone of modern biology and provides a naturalistic framework for understanding the complexity of life without supernatural design.

Monism: In the philosophy of mind, monism asserts that the mind and body are not distinct substances but one entity. Physicalist monism, in particular, argues that consciousness and mental states arise solely from physical processes in the brain, challenging dualistic notions that invoke a soul or spirit.

Strong atheists often argue that these and other scientific theories offer naturalistic explanations for phenomena traditionally attributed to divine action. They contend that invoking a supernatural entity is unnecessary and that science, though not yet complete in its explanations, is progressively unveiling the workings of a purely material universe. In addition to the scientific theories and hypotheses previously mentioned, strong atheists often draw on a broader spectrum of naturalistic explanations to account for various aspects of reality, challenging traditional theistic interpretations. These additional assertions and propositions encompass a range of disciplines, from physics and cosmology to biology and neuroscience.

Quantum Mechanics: This fundamental theory in physics provides a framework for understanding the behavior of particles at the subatomic level. Some atheists propose that quantum mechanics, with its inherent randomness and non-deterministic events, could offer insights into the origin of the universe and the apparent indeterminacy in the natural world, reducing the need for a divine prime mover.

Biogenesis: Going beyond abiogenesis, biogenesis focuses on the mechanisms of life's development and diversification after its initial emergence. This includes the complex processes of cell division, genetic inheritance, and molecular biology, all of which are explained through natural biochemical reactions and evolutionary principles.

Neuroscience and Consciousness: Advances in neuroscience have led to a deeper understanding of the brain's role in generating consciousness and mental phenomena. By mapping the correlations between neural activity and subjective experiences, strong atheists argue that consciousness can be fully explained as an emergent property of brain processes, negating the need for a soul or spiritual essence.

Anthropic Principle: Some atheists reference the Weak Anthropic Principle, which posits that our observations of the universe are necessarily conditioned by the fact that we exist within it. This principle suggests that while the universe's laws appear fine-tuned for life, this tuning is simply a prerequisite for our existence and observation, not evidence of divine design.

Sociobiology and Evolutionary Psychology:

These fields examine the biological basis of social behavior and psychological traits, attributing many aspects of human culture, morality, and religion to evolutionary pressures. Strong atheists might use these disciplines to argue that religious belief and moral intuitions are byproducts of evolutionary adaptations rather than divinely instilled truths.

Simulated Universe Hypothesis: While more speculative, some atheists entertain the possibility that our perceived reality is actually a sophisticated computer simulation. This hypothesis, inspired by advancements in virtual reality and computational complexity, challenges traditional notions of a physically real universe, although it raises further questions about the simulator's nature.

Emergence Theory: This scientific and philosophical concept describes how complex systems and patterns arise from the interactions of simpler entities. Atheists might use emergence to explain the origin of complex structures and phenomena in the universe, from galaxies to life forms, as natural outcomes of basic physical laws rather than the result of intelligent design.

Cultural Evolution: Beyond biological evolution, cultural evolution examines how ideas, beliefs, and technologies evolve over time through social transmission. Strong atheists may argue that religion itself is a cultural construct that evolved to meet various social, psychological, and existential needs, rather than a reflection of divine truth.

Natural Moral Philosophy: Some atheists propose naturalistic foundations for morality, based on human well-being, social cooperation, and evolutionary ethics. They contend that moral values can be objectively grounded in the consequences of actions on sentient beings, without recourse to divine commandments.

Cosmological Natural Selection: This speculative theory suggests that universes may reproduce through black holes, with each generation of universes potentially having different physical constants. Over time, this could lead to the selection of universes with properties conducive to the emergence of complexity and life, offering a naturalistic explanation for the fine-tuning of physical laws.

These additional propositions underscore the diversity of naturalistic explanations available to strong atheists in their endeavor to understand the cosmos, life, and human experience without invoking supernatural causes. While not all of these ideas are universally accepted or free from controversy, they collectively represent an attempt to construct a coherent, naturalistic worldview grounded in scientific inquiry and philosophical reasoning.

The various naturalistic explanations for the universe, life, and consciousness fall short of providing a compelling account of our reality. These explanations, ranging from multiverse hypotheses to the principles of quantum mechanics, and from the processes of abiogenesis to the complex theories of evolution and neuroscience, inherently lack the capacity to address the fundamental questions of purpose, meaning, and the origin of the "first cause."

The inadequacy of naturalistic explanations in several key issues related to Origins

The Problem of the First Cause: Many naturalistic hypotheses, such as quantum fluctuations, trace the universe's origin to a singularity or "nothingness." Yet, they fail to explain how something could emerge from nothing without an external cause, or in the case of virtual particles, the cause of a quantum field, supposedly giving rise to the virtual particles, leaving room for the notion of a "first cause" or "unmoved mover" as a more convincing explanation for the universe's existence.

Fine-Tuning and the Anthropic Principle: The precise tuning of physical constants necessary for life challenges naturalistic accounts like the multiverse hypothesis, which lacks empirical support. This fine-tuning is irrefutable evidence of a fine-tuner with purposes, goals, and foresight, pointing towards a universe intentionally crafted to support life. None of the proposed alternatives bear evidence, nor make sense. There is no reason to add a multitude of entities. Occam's razor is well applied here.

Consciousness and the Mind-Body Problem: Naturalistic explanations struggle to account for consciousness, subjective experiences, and the "hard problem" of consciousness. There is evidence that consciousness extends beyond mere physical processes. Penfield: The mind may be a distinct and different essence. I reconsider the present-day neurophysiological evidence on the basis of two hypotheses: (a) that man's being consists of one fundamental element and (b) that it consists of two.

Penfield: I conclude that there is no good evidence, in spite of new methods, such as the employment of stimulating electrodes, the study of conscious patients, and the analysis of epileptic attacks, that the brain alone can carry out the work that the mind does.

Moral Realism and Objective Values: The existence of objective moral values challenges the naturalistic view, as purely naturalistic explanations fail to ground these values, hinting at a transcendent source of morality. If you agree, that its wrong in any circumstances to rape, torture, and kill little babies for fun, then you agree that objective moral values exist. Since they objectively exist, but do not exist in the material realm, the moral law was made by Someone Who lives in the immaterial realm.

The Existential and Metaphysical Questions: Naturalistic approaches fall short in addressing existential questions about meaning, purpose, and ultimate reality, pointing to the fact that there are aspects of reality that transcend the empirical realm. The perspective that life is a fleeting, accidental occurrence in the vast cosmos leads to a sense of existential nihilism—the belief that life is without objective meaning, purpose, or intrinsic value. From this viewpoint, if we are merely the by-products of random events in the universe, then any meaning we ascribe to our existence is self-delusional because it is an attempt to impose significance on something that, at its core, is devoid of inherent meaning. Self-ascribed meaning is inherently flawed because it relies on one's subjective perspective, which is transient and limited. If our existence is the result of accidental cosmic events, then any meaning we derive from our experiences, relationships, and achievements is temporary and ultimately insignificant on the cosmic scale. Any personal or collective sense of purpose is a construction, a mere distraction from the fundamental meaninglessness of existence.

Origins of Life (Abiogenesis): The transition from non-living matter to life poses significant challenges for naturalistic hypotheses, which have yet to fully explain or replicate this process, hinting at the possibility of an external guiding force or intelligence. In over 70 years of scientific experiments, scientists have failed to elucidate any of the required steps, to go from the goo, to a fully self-replicating, autonomous living cell.

Information in DNA: The complex information within DNA, the genetic code operating like a translation manual, and the mechanisms required for its processing point to the involvement of an intelligent source, refuting naturalistic explanations. The odds to create even just one of the myriads of proteins required to have a first living cell, are beyond the probabilistic resources of the entire universe, even giving the entire life span of 13,8 billion years, to do the shuffling and attempts.

Laws of Nature: The uniformity and existence of the laws of nature, essential for a habitable universe, raise questions about their origin and finely-tuned parameters, challenging naturalistic frameworks that take these laws for granted.

Mathematical Universality: The "unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics" in describing the physical world suggests a pre-existing harmony between abstract mathematical principles and the universe's structure, pointing towards a transcendent rational mind.

Language and Symbolic Thought: The human capacity for language and abstract reasoning exceeds what natural selection and adaptive advantages alone can account for, suggesting a different origin for these cognitive abilities.

Aesthetic Experience: The human experience of beauty and the drive to create art challenges purely naturalistic explanations, suggesting that our aesthetic impulses may point to a reality beyond the material.

Altruism and Sacrificial Love: Instances of genuine altruism and sacrificial love, particularly when they confer no evolutionary advantage, challenge naturalistic accounts based on genetic self-interest or social cooperation.

Religious Experience: The prevalence of religious experiences and a sense of the numinous across cultures suggest dimensions of human consciousness and reality beyond what naturalistic explanations can fully encompass.

These examples underscore the challenges faced by naturalistic propositions in accounting for the full spectrum of human experience and the intricacies of the cosmos, suggesting the need for a broader explanatory framework that can encompass both the empirical and the transcendent aspects of reality. Naturalistic explanations fall short of addressing the deeper, metaphysical questions that define our existence. The limitations and gaps in these explanations, coupled with the profound intuition of purpose and design in the cosmos, provide a compelling case for a transcendent, intelligent cause at the foundation of all reality.

Atheist Professor Graham Oppi Gives REAL Definition of Atheism (very based): "Atheism is the view that there are no Gods" 1

Negative atheism, also called weak atheism and soft atheism is any type of atheism where a person does not believe in the existence of any deities but does not explicitly assert that there are none. Link

Positive atheism, also called strong atheism and hard atheism is the form of atheism that additionally asserts that no deities exist

Agnosticism is the view that the existence of God, of the divine or the supernatural, is unknown or unknowable. An agnostic can also hold neither of two opposing positions on a topic. Link

Skepticism (American English) or skepticism is generally any questioning attitude or doubt towards one or more items of putative knowledge or belief. Link

Freethought (or "free thought")is a philosophical viewpoint that holds that positions regarding truth should be formed based on logic, reason, and empiricism, rather than authority, tradition, revelation, or dogma Link

Anti-Theism The view that theism, religion, and belief in God must be opposed. The individual believes that religious belief is both dangerous and harmful. Anti-theists are often Strong Atheists. Link

Apatheism The individual lives as if there are no gods and explains natural phenomena without invoking the divine. Typically the individual doesn’t care whether or not God exists. Link

Explicit Atheism The individual makes a positive assertion regarding their lack of belief in God and/or gods. Implicit Atheism The absence of belief in one or more gods, without a conscious rejection of it. Link

There are further categorizations and nuances within atheism related to various philosophical, ethical, and epistemological stances. These categorizations often intersect with broader worldviews and can provide more specific insights into an individual's perspective on religion, deities, and the supernatural.

Practical Atheism: This stance involves living one's life without any reference to gods or deities, regardless of one's theoretical belief in them. Practical atheists may not spend much time considering the existence of deities because it has no practical impact on their daily lives.

Theological Noncognitivism: This is the position that religious language, particularly discourse about God or gods, is not cognitively meaningful. It suggests that statements like "God exists" do not express propositions that can be true or false in any meaningful sense. This can lead to a form of atheism because it denies the coherence of theistic claims.

Ignosticism: Similar to theological noncognitivism, ignosticism is the view that a coherent definition of God must be presented before the question of the existence of God can be meaningfully discussed. If the definition is unfalsifiable, the ignostic takes the theological noncognitivist stance that the question is meaningless.

Secular Humanism: While not strictly a form of atheism, secular humanism is a worldview and ethical system that emphasizes human well-being, ethical values, and natural explanations for phenomena without recourse to the supernatural. Many secular humanists are atheists, as they do not include the divine in their ethical or philosophical considerations.

Atheistic Religion: Some religions or belief systems, such as certain forms of Buddhism and Jainism, do not include a creator god in their doctrine, which makes them atheistic in a sense. However, followers may still engage in religious practices, and rituals, and hold spiritual beliefs.

Atheism and Spirituality: Some atheists identify as spiritual, finding awe and wonder in the natural world, humanity, and the universe without attributing these feelings to a deity. This form of atheism recognizes a sense of connectedness or transcendence that does not rely on traditional notions of theism.

Post-Theism: This stance posits that humanity is in a post-religious phase where the concept of god is unnecessary for explaining natural phenomena or for providing ethical guidelines. It sees theism as a historical phase that humanity has evolved beyond.

These categorizations show the diversity within atheism and related stances, highlighting that disbelief in deities can come with a variety of philosophical underpinnings and implications. Individuals may identify with multiple categories simultaneously, and these labels can often overlap or be used in combination to describe one's specific viewpoint.

Claim: Atheism is just about the rejection of the claim of the existence of God because there is no evidence for his existence. I am just not convinced about your arguments of God's existence.

Reply: The discussion around atheism often becomes tedious when individuals presume the need to educate others on its principles as if this would be the first encounter with such explanations. Atheists, like everyone else trying to make sense of the world, are not exempt from the burden of proof. Atheists believe that the significant questions of life can be addressed without resorting to the notion of a divine supernatural entity. In contrast, theists observe that naturalistic explanations often fall short, suggesting that the idea of an intelligent, transcendent force provides a more convincing explanation. In such instances, theists consider it logically sound to deduce a supernatural origin.

Atheism, in its essence, is defined by the rejection of a personal god. However, the spectrum of atheistic belief is broad, encompassing deists who accept a non-interventionist creator, agnostics who remain uncertain about the divine, materialists who deny anything beyond the physical, and even those who subscribe to panpsychism, believing in the inherent intelligence of the cosmos. Therefore, "atheist" serves as a catch-all term for anyone who does not identify as a theist.

Does atheism just as a ‘lack of belief’ make any sense?

Claim: Atheism is not a religion or philosophy. It is simply a lack of faith or belief in God(s).

Answer: The assertion "I lack belief in a god" is a stance frequently adopted by atheists, likening their skepticism about God to disbelief in fantastical notions such as invisible pink unicorns. They claim to maintain a neutral stance, devoid of any belief or disbelief regarding divinity, treating the subject as inconsequential. However, this perspective overlooks a critical aspect of human cognition: once introduced to an idea, neutrality is no longer viable. Exposure to a new concept necessitates some form of cognitive response, whether it's outright dismissal, contemplation of its validity, acceptance, rejection, or any stance in between. The claim of returning to a pre-exposure state of non-belief, defined as an absence of cognitive engagement, is untenable. Consider a child unaware of the concept of invisible pink unicorns. Upon learning of this concept later in life, the child must inherently form an opinion, ranging from belief to skepticism, amusement, indecision, or deferred judgment. The exposure compels the child to adopt a stance, moving beyond the initial state of unawareness. Some might argue that deferring judgment aligns with atheistic views on non-belief. However, choosing to withhold judgment following exposure to an idea is a form of engagement, differing from a lack of awareness. This stance, akin to agnosticism, reflects an open-mindedness to new information, acknowledging the possibility of the concept's existence pending further evidence. This is distinct from atheism, which is often characterized by a definitive lack of belief. To illustrate, consider the hypothetical suggestion of an ice cream factory on Jupiter. Upon hearing this, one might react with skepticism, amusement, curiosity for evidence, or whimsical musings about interplanetary ice cream. Such a notion is instinctively categorized as implausible, demonstrating that exposure to an idea inevitably leads to some form of judgment, thereby challenging the possibility of maintaining a true state of non-belief.

The argument that one can simply "lack belief" in a deity, as often claimed by atheists, overlooks the inherent human tendency to evaluate and categorize ideas from full endorsement to outright dismissal. This natural inclination challenges the notion of passive non-belief. Consider the analogy of animals and their apparent absence of belief in deities. For instance, my bulldog Bobby, a remarkably intelligent and engaging pet, demonstrated no understanding or belief in the concept of God. This lack of belief, however, doesn't classify him or other non-sentient entities like infants, plants, or inanimate objects as atheists. Atheism, in this context, seems applicable only to sentient beings capable of contemplating such concepts. Yet, the broader assertion by some atheists that their stance is merely a "lack of belief" seems to sidestep a more profound engagement with the philosophical and theological discussions surrounding atheism. This stance can be seen as a way to avoid the scrutiny and critique that comes with holding a more defined position. The growing discourse and critique from various religious and philosophical perspectives are challenging atheistic positions more rigorously, prompting a more defensive posture from the atheist community. This discourse is not just an intellectual exercise but a reflection of a deeper search for truth, with significant implications for the validity and sustainability of atheistic beliefs in the face of growing scrutiny and debate.

The assertion that atheism equates to a lack of concern is contradicted by the actions of many vocal atheists, who actively engage in discussions and debates about their disbelief. This suggests that atheism, for some, goes beyond the mere absence of belief in deities to a more defined stance, often articulated as the belief in the nonexistence of God. This active engagement raises questions about the depth and substance of one's identity if it primarily revolves around a disbelief in something. Weak atheists center on critiquing the beliefs of others rather than proposing a constructive worldview of their own. This comparison is drawn to highlight an inconsistency: while one might not actively campaign against belief in UFOs due to personal disbelief, some atheists adopt a more proactive stance in expressing their disbelief in God. The conversation around atheism often blurs the lines between weak atheism, agnosticism, and strong atheism, with various strategies employed to argue against theistic beliefs. Some atheists might use evasive tactics, such as claiming ignorance or deferring to science, as a means to sidestep deeper philosophical discussions about naturalism and the existence of a deity. This can come across as intellectual dishonesty, where the refusal to believe in a deity is seen not as a neutral lack of belief but as a deliberate choice influenced by personal will. The debate extends to the nature of evidence and belief. When atheists assert the absence of proof for a deity's existence, it raises the question of whether their stance on the natural world is similarly based on faith, given the lack of definitive proof that the natural world is all there is. This challenges the notion that atheism is a purely passive absence of belief, instead, it is an active choice to reject theistic evidence, which is often dismissed out of a reluctance to engage with the possibility of a deity's existence.

While asserting rational and open-minded approaches, some atheists are being closed off to any evidence or reasoning that might evidence the existence of God, which is a form of willful ignorance rather than true rational skepticism. Furthermore, the discussion often involves atheists making accusations of theists misunderstanding or oversimplifying concepts like atheism and evolution, which are evasive tactics rather than substantive arguments.

In his essay "Herding Cats: Why atheism will lose," Francois Tremblay suggests that atheism's credibility is undermined if atheists cannot substantiate their fundamental beliefs about reality and cognition, likening unfounded atheism to a "paper tiger." A meaningful stance on atheism requires intellectual engagement and the willingness to substantiate disbelief with reasoned arguments.

Why the “I Just Believe in One Less God than You” Argument Does Not Work

Argument: “I contend we are both atheists, I just believe in one less god than you do. When you understand why you dismiss all the other possible gods, you will understand why I dismiss yours.” Another way to phrase it: “I don’t have to take the time to reject Christ any more than you have to take the time to reject all the millions of gods that are out there. It just happens by default. The justification for my atheism is the same as yours concerning your rejection of all the other possible gods.” And another: "I don’t believe in Yahweh. I don’t believe in Hercules either."

Response: In addressing the contention that the distinction between atheists and theists is merely the disbelief in one additional deity, it's essential to delve into the nuanced nature of divine belief. The monotheistic concept of God stands apart from the pantheon of polytheistic gods not merely in number but in the very essence of divinity. Within the monotheistic framework, God is not envisioned as another entity within the cosmos but as the foundational underpinning of all reality, the very bedrock upon which existence itself is contingent. This conceptualization transcends the realm of superhuman beings governing specific domains, characteristic of polytheistic traditions, and ventures into a philosophical domain where God is the necessary "unmoved mover" or "first cause," a principle without parallel in the realm of polytheism.

The argument often overlooks the epistemological distinctions between innate knowledge and constructed beliefs. Monotheistic traditions posit an inherent, intuitive knowledge of a creator, discernible through the natural world's complexity and order, contrasting sharply with the culturally constructed deities of polytheism, which often fulfill explanatory or societal roles. Moreover, the dismissal of all deities based on the rejection of some neglects the independent lines of evidence and reasoning that might underpin the belief in a specific monotheistic God, such as cosmological, teleological, or moral considerations.

Asserting that atheism and theism differ only in the rejection of one additional god implies a false equivalence, treating all concepts of divinity as interchangeable and dismissible on identical grounds. This perspective fails to engage with the unique arguments and experiences that support a monotheistic belief, which demands consideration on its terms. Such a stance also involves a category error, erroneously equating the monotheistic God, not as a being within the universe but as the very ground of being and existence, with gods that, however powerful, exist within the universe's confines.

Furthermore, the historical and cultural evolution of religious beliefs from polytheism to monotheism in various traditions often reflected deeper philosophical and theological exploration rather than a mere reduction in the number of deities. The diversity of religious expressions and the multiplicity of gods across cultures might better be understood as humanity's manifold attempts to comprehend and articulate the divine, rather than evidence against the existence of a singular, ultimate deity.

In summary, the debate transcends a simplistic comparison between atheism and theism based on the number of gods rejected. It invites a deeper exploration into the nature of belief, the philosophical underpinnings of monotheism, and the logical and epistemological considerations that distinguish a grounded belief in a singular, foundational deity from the dismissal of an array of mythological figures.

The Burden of Proof: Is It Solely the Responsibility of Theists to Provide It?

The discourse around the burden of proof in debates between theists and atheists is often charged and polarized. In discussions about the existence of God, theists are typically asked to provide evidence for God's existence. This expectation is based on the philosophical principle that the one making an affirmative claim carries the burden to substantiate it. However, atheists, too, should bear a burden of proof, particularly when they posit naturalistic explanations for phenomena traditionally attributed to divine intervention or creation. If atheists challenge theistic views, they should also provide positive evidence for their naturalistic viewpoints, rather than solely critiquing theistic claims. A more constructive approach would involve articulating and defending a naturalistic view of the universe that explains the existence of the universe, life, biodiversity, and consciousness. Theists are not the only ones who have the burden of proof. Anyone making claims about the nature of reality, whether theistic or naturalistic, should be prepared to support their claims with evidence. This calls for a more balanced discourse where both sides are expected to present well-reasoned, evidence-based arguments for their respective worldviews, be they theistic, atheistic, or otherwise.

Is there a dispute between Science and Religion?

The most profound ideological conflict isn't between science and religion, which often find ways to coexist harmoniously, but rather between the philosophical perspectives of naturalism and theism. These viewpoints offer fundamentally different interpretations of reality and existence. Like abstract concepts such as numbers and logical principles, metaphysics transcends sensory experience, placing the debate between naturalism and theism firmly within the philosophical domain. Metaphysical naturalism posits that the entirety of reality is confined to the physical matter and energy within space-time, dismissing any existence beyond the natural world. This perspective inherently rejects supernatural entities or phenomena, such as deities, souls, or other spiritual beings, and negates the notion of an overarching purpose or design in the universe, as it denies the existence of any conscious designer. Conversely, theism presents the universe as the creation of a Supreme Being who not only initiated its existence but continues to sustain it, existing beyond the physical boundaries of the universe. By their very nature, these two ideologies are in direct opposition to one another. In the discourse surrounding the origins and complexity of life and the universe, Intelligent Design has been positioned as an emerging scientific theory on the cusp of gaining acceptance within the scientific community. A scientific theory is defined as a well-substantiated explanation for the natural world, one that is formulated based on rigorous testing, observation, and analysis in line with the scientific method. This process includes the critical examination of hypotheses through empirical study and the validation of findings according to established scientific standards.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: "Science is the philosophy of discovery. Intelligent Design is the philosophy of ignorance. " 2

Response: "Science is the tool of discovery. The awe-inspiring discovery is that science confirms an intelligent designer. "

Science, in its essence, is a remarkable tool of discovery that continuously unveils previously unfathomable complexities and the majestic order of the universe. It's a journey through which humanity explores the vastness of space, the minutiae of cells, and the enigmatic laws of physics. This journey of discovery, far from distancing us from the notion of an intelligent designer, brings us closer to the awe-inspiring realization that the universe operates with precision and harmony that evidence a purposeful and intentional setup. Either in the quantum realms or farther in the cosmic expanse, we encounter patterns, laws, and a level of complexity that borders on the poetic. The constants and equations that govern the universe, the fine-tuning necessary for life to exist, and the beauty found in the natural world from the spirals of galaxies to the DNA's double helix structure, all evoke a sense of wonder and imply a designed instantiation. Moreover, the capacity for humans to appreciate beauty, pursue truth, and ponder their existence in the universe suggests a dimension of reality beyond mere survival and reproduction. These pursuits, while not tangible or quantifiable in the same way physical phenomena point to a depth of human experience that material explanations alone do not fully encompass. In this context, the idea of an intelligent designer is not necessarily at odds with the scientific endeavor but can be seen as a perspective that enriches our understanding of the universe. It invites us to consider not just how things are but why they might be, encouraging a holistic view of existence that marries the empirical with the existential. Thus, the unfolding revelations of science, rather than diminishing the possibility of an intelligent designer, amplify our sense of wonder and appreciation for the complexity and beauty of the world around us, pointing towards a greater purpose and design behind the cosmos.

Strong atheism is a faith-based worldview

Communal Gatherings: Atheists have formed communities and congregations that mirror the social and communal aspects of religious worship. Examples include "godless churches" and secular assemblies where individuals gather, not to worship deities, but to enjoy a sense of community, discuss ethical and philosophical issues, and support each other in their shared disbelief.

Foundational Texts: While not revered as divine scripture, works such as "The Atheist's Bible" serve as compilations of thoughts, arguments, and reflections that provide a foundation for atheist viewpoints, much like religious texts do for believers. These texts offer insights, moral philosophies, and reflections on the nature of the universe without appealing to a higher power.

Philosophical Frameworks: Atheism, particularly in its strong or "positive" form, which asserts the non-existence of gods, often relies on systematic philosophical arguments. Texts that outline atheism's reasoning against theological concepts provide a structured ideological framework that parallels the doctrinal treatises found in religious traditions.

Evangelism: Although atheism inherently lacks the divine mandate that often drives religious proselytization, some atheists actively engage in spreading their disbelief in gods, critiquing religious beliefs, and advocating for secularism. This "evangelical" aspect, where individuals are passionate about sharing and defending their atheistic views, resembles the missionary zeal found in many religions.

Prominent Figures: Just as religions have their revered leaders, prophets, or popes, atheism has its notable figures who are highly respected, influential, and often looked up to for guidance and inspiration. These individuals, through their writings, speeches, and debates, shape the atheistic discourse, much like religious leaders shape the faith and practices of their followers.

The perspective often associated with atheism, although not universally held or acknowledged by all who identify as atheists, implies a set of understandings about the universe that do not necessitate a divine creator. This worldview would suggest:

1. The existence and functionality of the natural world do not require a supernatural creator.

2. The complexity and order observed in nature arise naturally by unguided means, without the need for an intelligent designer.

3. The universe could have originated from natural phenomena, without the intervention of a divine force, or it might be part of an eternal cosmos.

4. The laws governing the physical universe emerge from its inherent properties, rather than being decreed by a higher power.

5. The apparent fine-tuning of universal constants and conditions could be a result of natural processes or multiple universes, rather than the actions of a purposeful designer.

6. Life and its origin can be explained through natural, chemical, and biochemical processes without invoking a supernatural life-giver.

7. The emergence of complex information, such as genetic codes, can be accounted for by chemical selection and/or eventually other evolutionary mechanisms.

8. Biological structures and systems can develop through evolutionary processes without the need for a divine architect.

9. The diversity of life on Earth can be understood through the theory of evolution, which explains how natural selection and genetic variation lead to speciation.

10. Consciousness and moral values can be seen as emergent properties of complex brain functions, not bestowed by a divine entity.

11. Meaning and purpose in life can be derived from personal experiences, relationships, and achievements, rather than being assigned by a higher power.

12. The concept of an afterlife is not necessary to give life significance or to understand human consciousness.

13. The lack of empirical evidence for deities is viewed not as a dismissal of the possibility but as a basis for focusing on the natural and observable world.

The Biblical Perspective on Atheism

The biblical perspective on atheism is deeply intertwined with its broader theological and moral teachings. Central to this perspective is the assertion found in Psalm 14:1, which declares, "The fool says in his heart, 'There is no God.'" This statement encapsulates the biblical stance that denying God's existence is not only mistaken but also a reflection of folly and moral corruption. From the outset, the Bible affirms the existence of God as a fundamental truth, beginning with the emphatic declaration in Genesis 1:1, "In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth." This foundational assertion sets the stage for understanding the biblical view of reality, one that is inherently theistic and sees God's creative power as evident in the world. The Bible articulates that the evidence of God's existence is manifest in the natural world, a principle echoed in Romans 1:20. This passage argues that God's "invisible qualities" are clearly perceived in the created order, rendering disbelief in God as indefensible and without excuse. Such a perspective implies that atheism is not a conclusion arrived at through impartial reasoning but is influenced by a predisposition toward unrighteousness and a rejection of divine authority. Ephesians 4:18 and Revelation 21:8 extend this argument, suggesting that atheism and other forms of unbelief are symptomatic of a deeper spiritual and moral estrangement from God. This estrangement is characterized by ignorance, hardness of heart, and a proclivity toward behaviors that are antithetical to God's moral law. The biblical narrative also posits that the natural world, in all its diversity and complexity, inherently points to a creator. This is illustrated in Job 12:7-9, where the harmony and order of the natural world are presented as testimonies to God's handiwork. Even the demons, as mentioned in James 2:19, acknowledge God's existence, further underscoring the irrationality of atheism from a biblical standpoint. The Bible presents atheism not merely as an intellectual position but as one rooted in moral and spiritual rebellion against God. It challenges the coherence of atheism by highlighting the evident design and purpose in creation, which testify to a Creator. The biblical critique of atheism extends beyond the mere denial of God's existence to address the underlying spiritual condition that fosters such disbelief. In doing so, the Bible shifts the focus from the question of God's existence to the nature of one's relationship with the true God, emphasizing the importance of knowing and worshiping God as revealed in the scriptures and through Jesus Christ.

Understanding the outspokenness of Atheists