On Amazon:

From Forensics to Faith: The Shroud of Turin's History and Authenticity Under Scrutiny

Paperback:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0CV81QVH9/

Kindle version:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0CV65HNTD/

The infographic panels can be downloaded here:

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1yUUQfz_CGQejruIJwOKMMX8xNluAhPjL?usp=sharing

Joe Marino, Author of: The 1988 C-14 Dating Of The Shroud of Turin: A Stunning Exposé

Grasso’s book is an up-to-date treatment of the mysterious Shroud of Turin, believed by many to be the actual burial cloth in which Jesus was buried, although there are numerous skeptics who believe the Shroud is nothing but a clever medieval forgery.

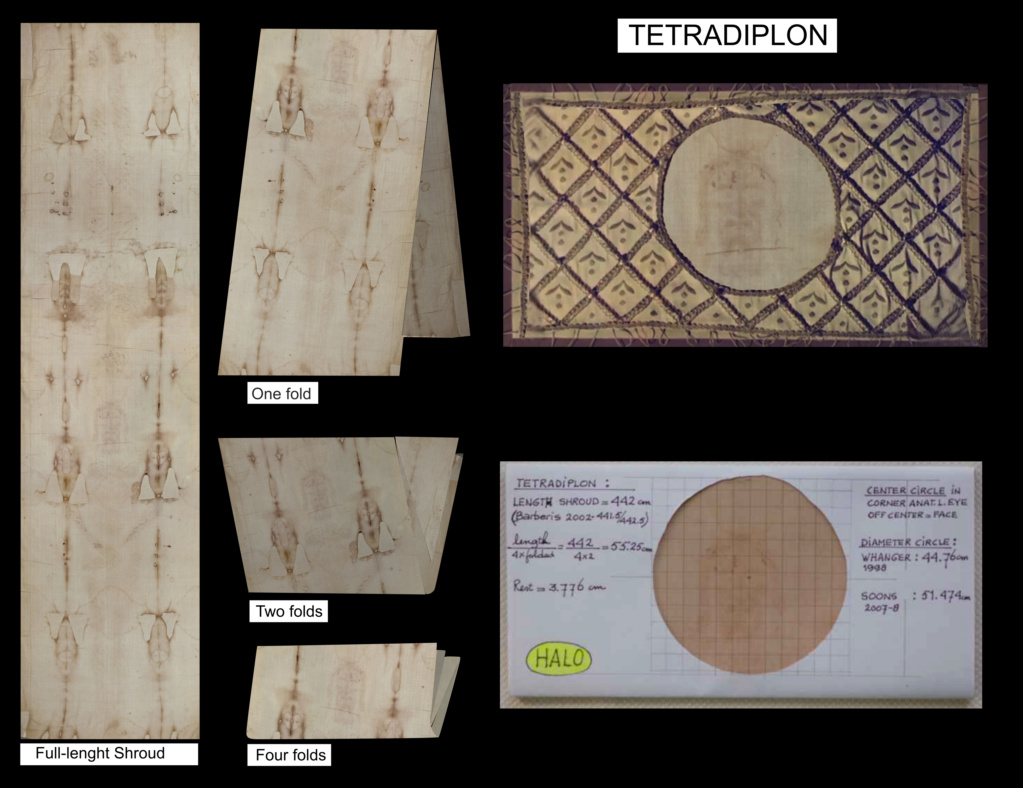

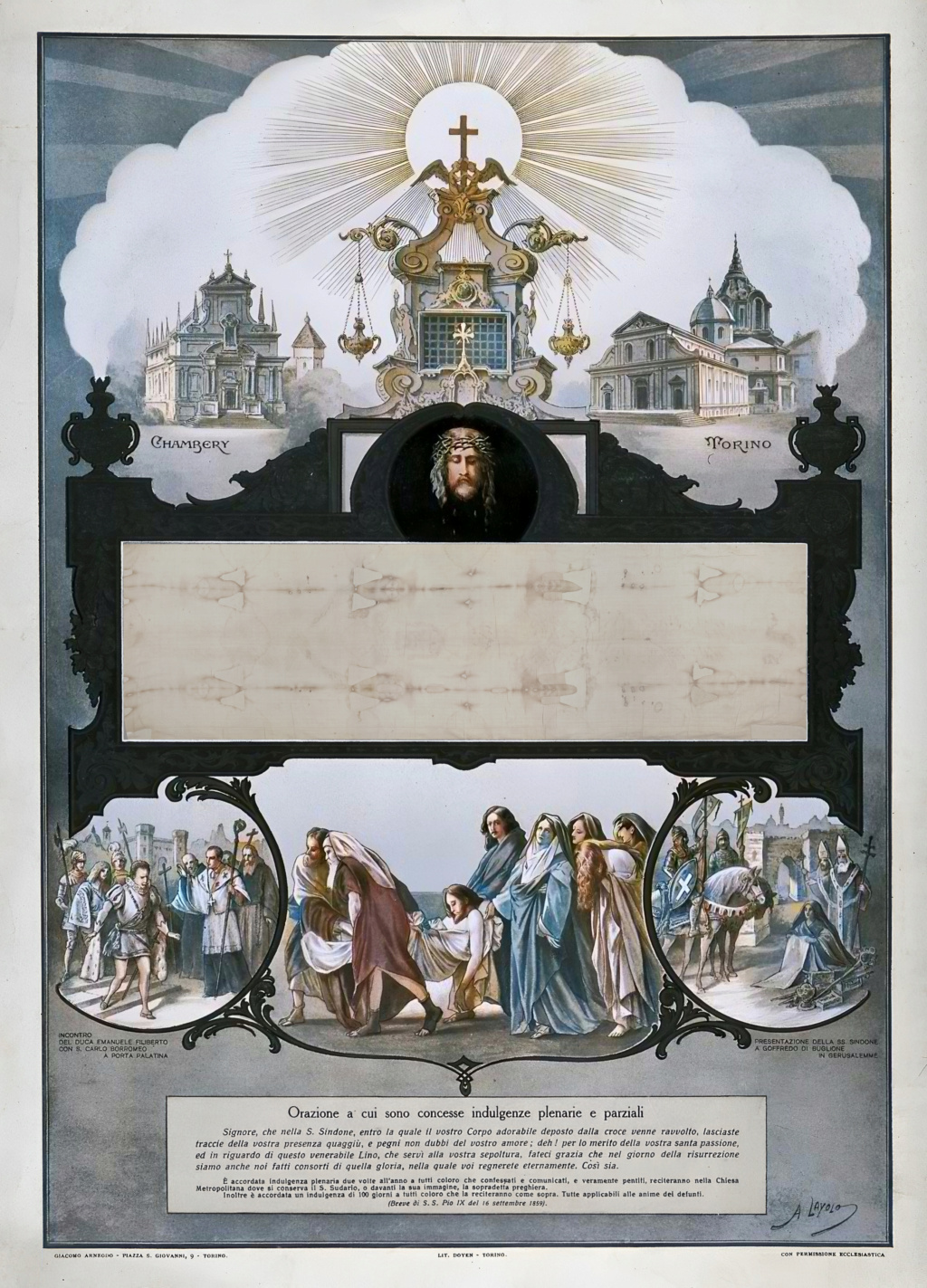

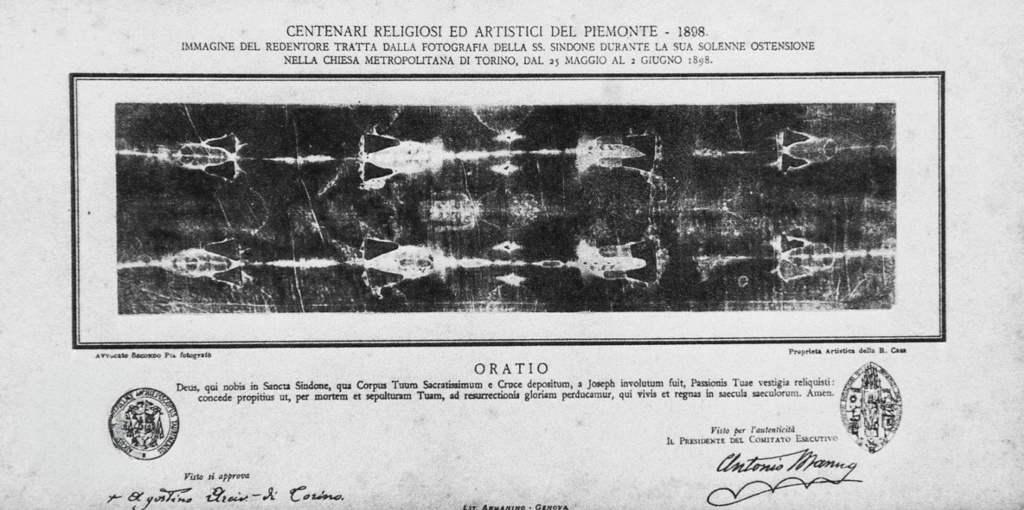

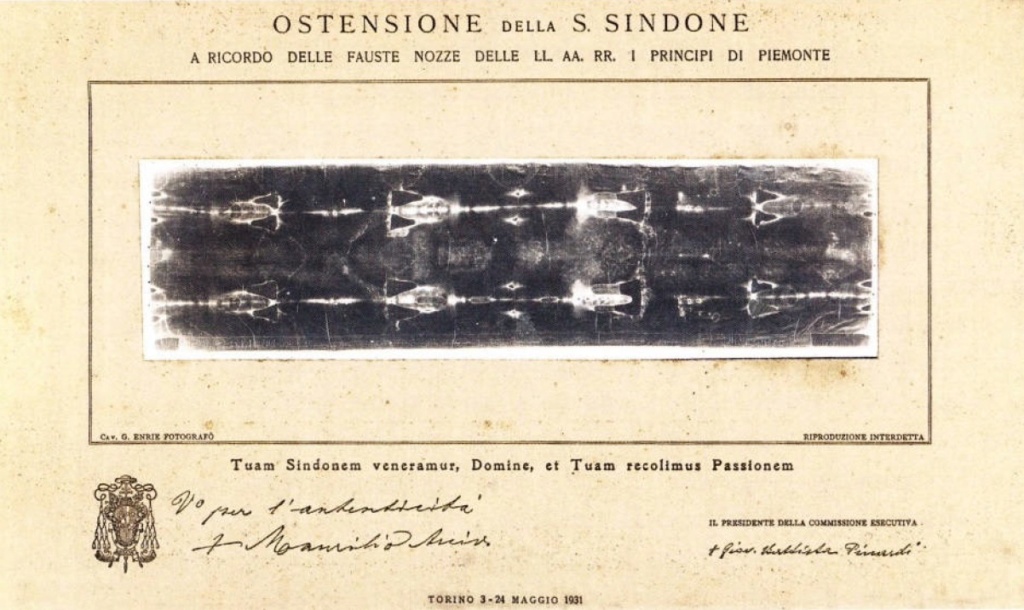

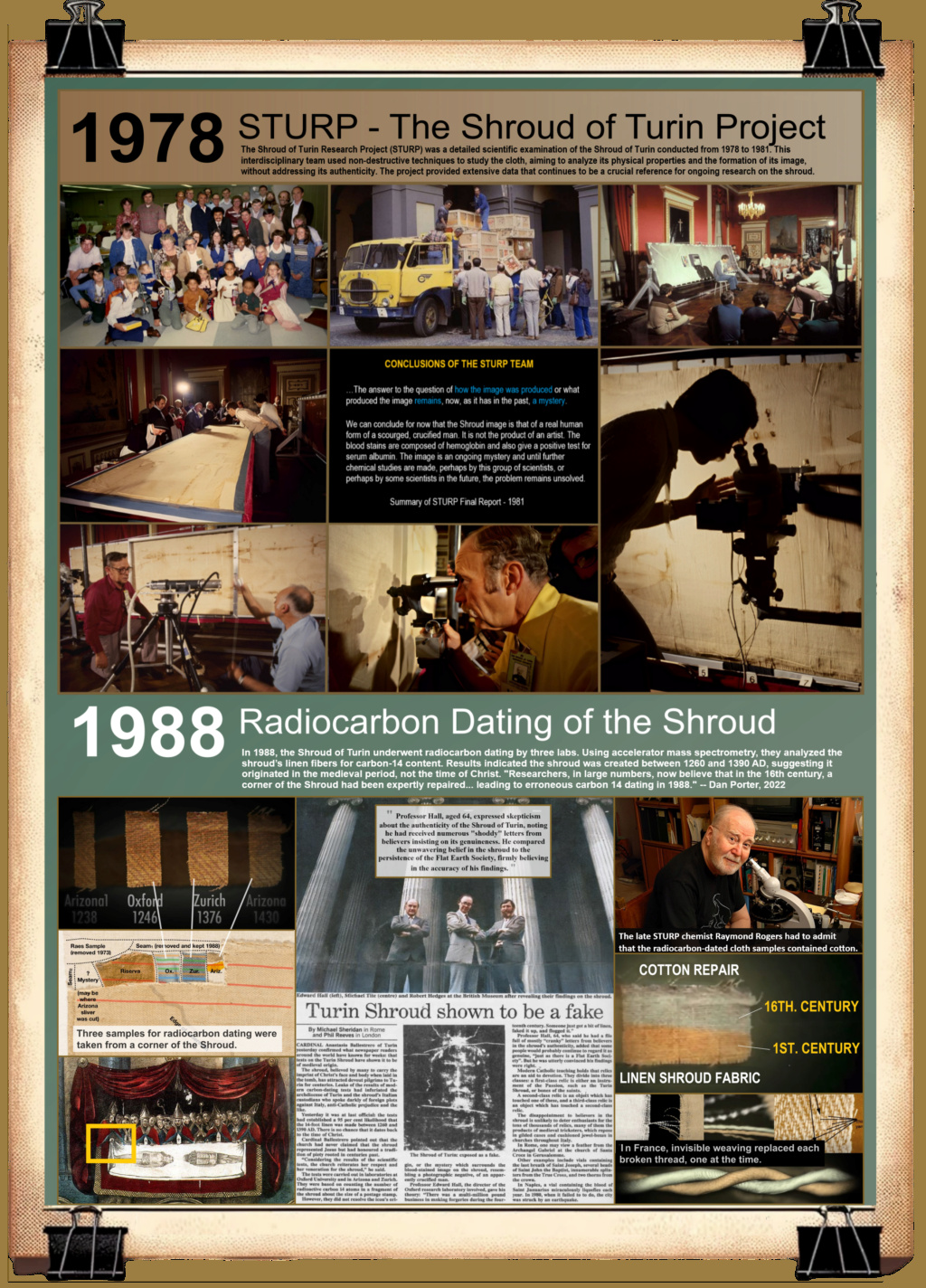

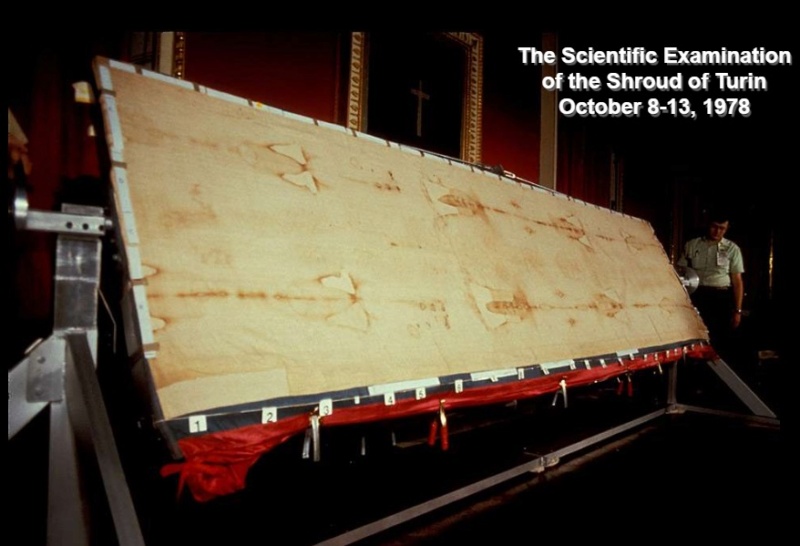

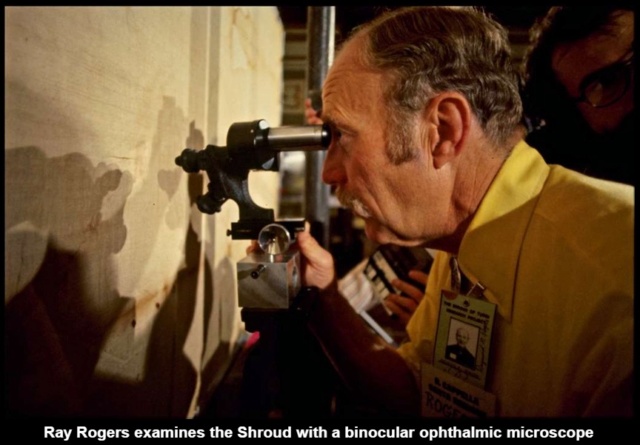

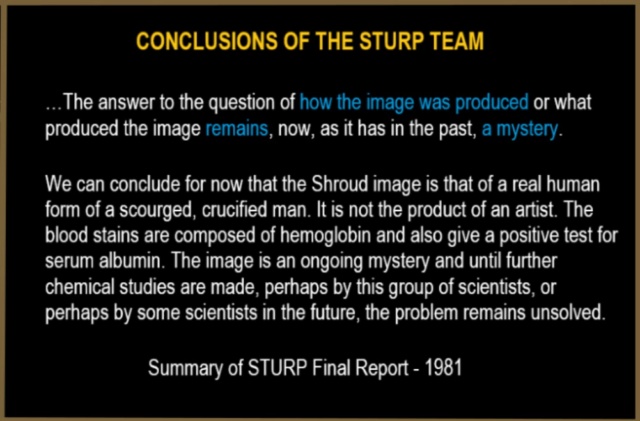

Grasso painstakingly examines all aspects of the Shroud and incorporates recent “infographics,” with its many excellent photos and graphics that complement the text. He meticulously analyzes the Shroud’s correspondence with the gospel accounts; a detailed look at the mechanics of crucifixion; the Shroud’s possible history back to the 1st century; the science of the Shroud from the first photos taken in 1898; the extensive 1978 examination of the Shroud by “The Shroud of Turin Research Project;” the unique image properties of the images, including blood, pollen and 3D information; the infamous C-14 dating in 1988; various proposed hypotheses of how it could have been faked; the virtual impossibility of it having been forged, textile analysis, including Old Testament and New Testament background; a look at the Sudarium of Oviedo, believed by some to be the face cloth mentioned in the Gospel of John; the Shroud’s link with the Resurrection, the implications of the Shroud and addresses common objections against the Shroud’s authenticity.

This is one of the finest books on the Shroud available and should be in the library of anyone interested in the Shroud.

Robert A. Rucker, nuclear engineer, www.shroudresearch.net

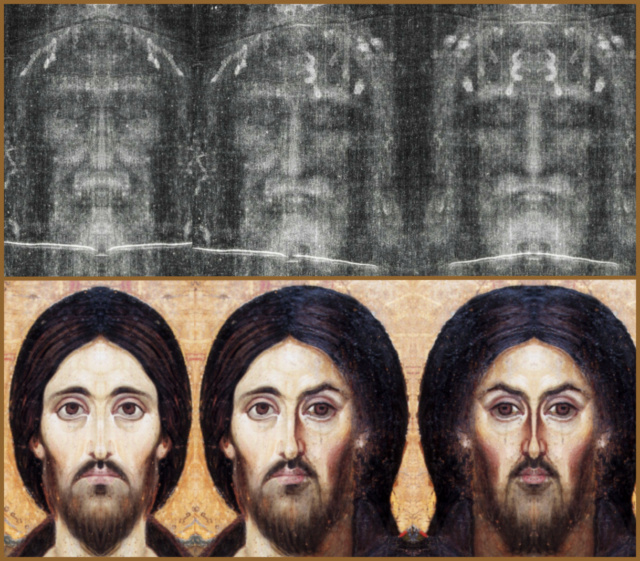

The 2024 book “From Forensics to Faith” by Otangelo Grasso covers extensive discussion of all essential topics related to the Shroud of Turin in about 540 pages. This includes what can be seen on the Shroud (Chapter 1), history of the Shroud (Chapters 2 to 4), scientific examination (Chapters 5 and 6) and carbon dating of the Shroud (Chapters 7), how the images were produced (Chapters 8 and 9), fabric, blood, and other evidence (Chapters 10 to 13), comparison of the Shroud to Biblical evidence (Chapters 14 to 20), and meaning of the Shroud for us today (Chapters 21 and 22). Of special delight is the images created by the author related to the Shroud and Jesus, especially Jesus’ face on the cover of the book that was produced from the front image on the Shroud. What a delight it would be to leave this book face up on your coffee table or other prominent location to allow others to see the face of the most important person who ever lived.

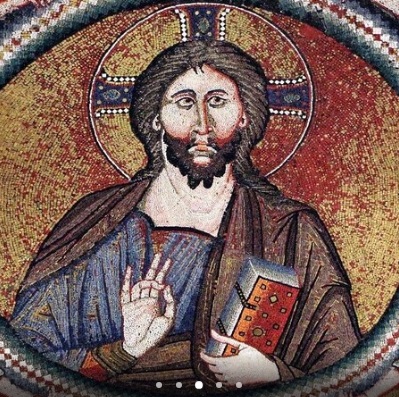

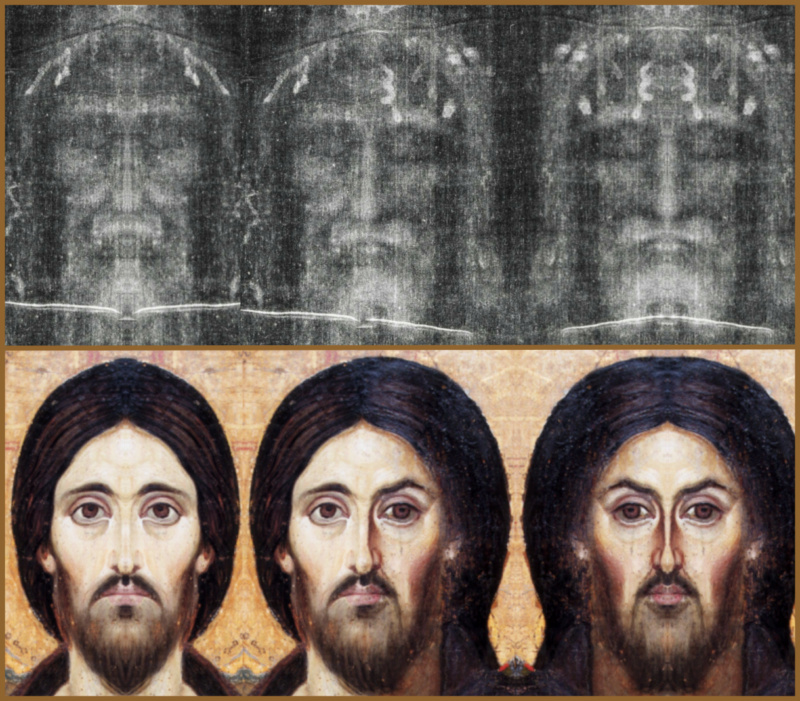

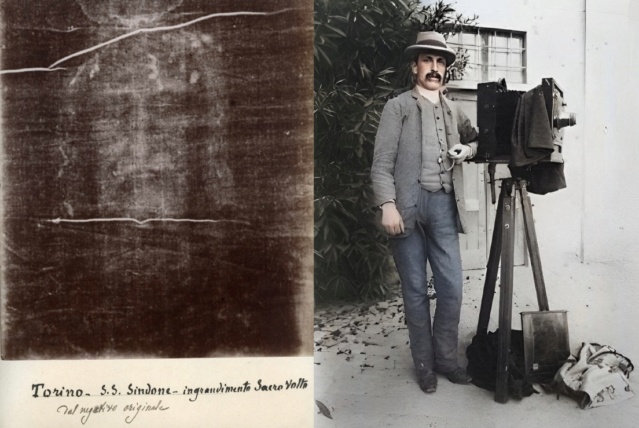

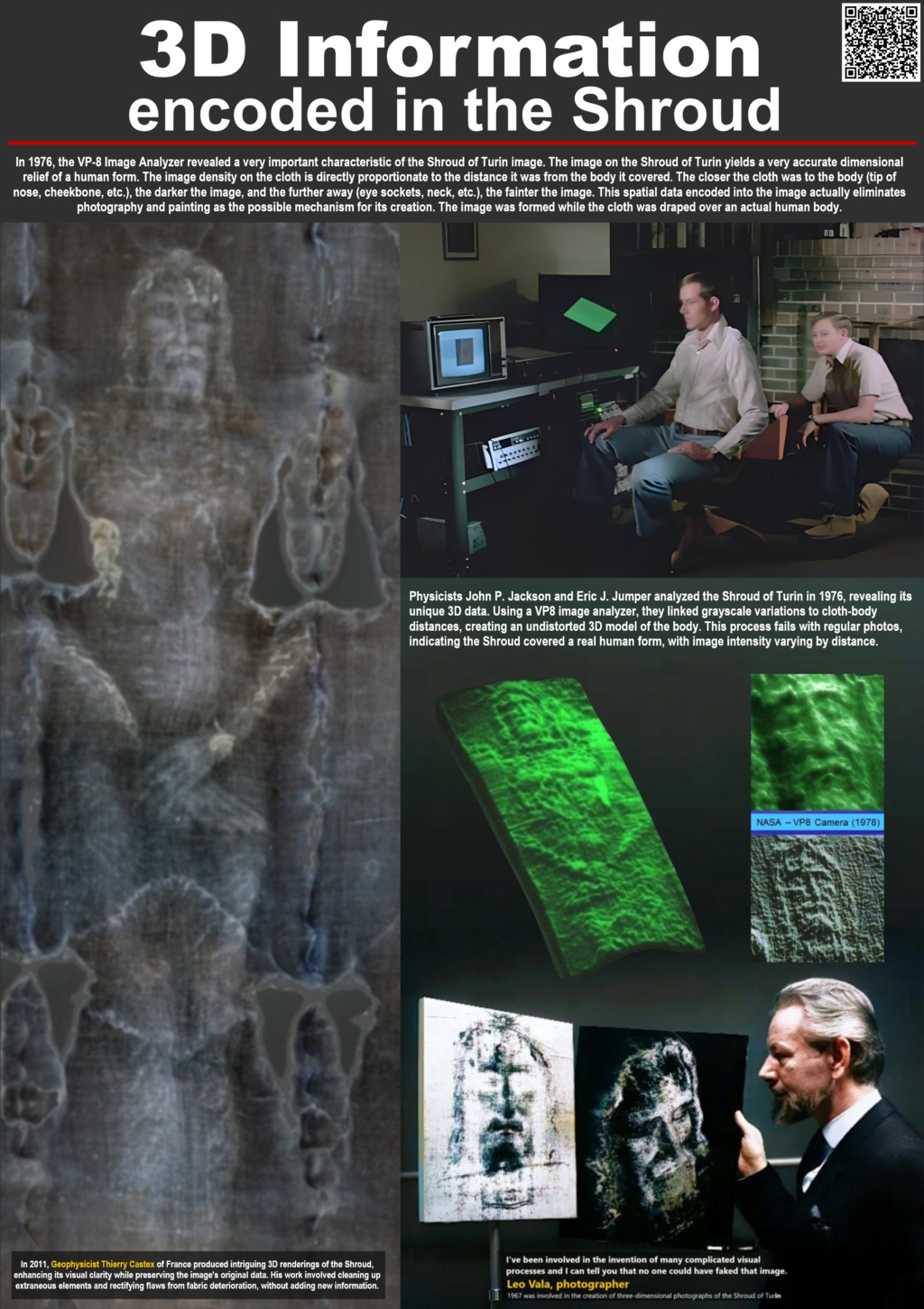

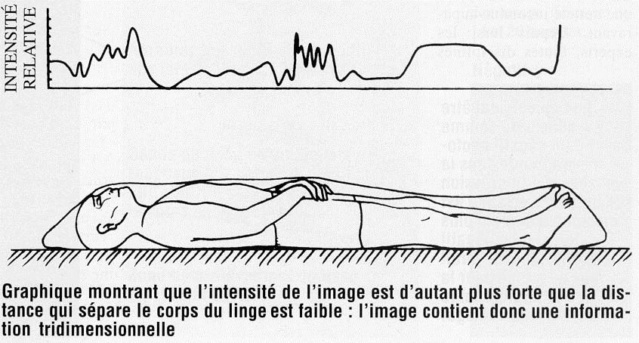

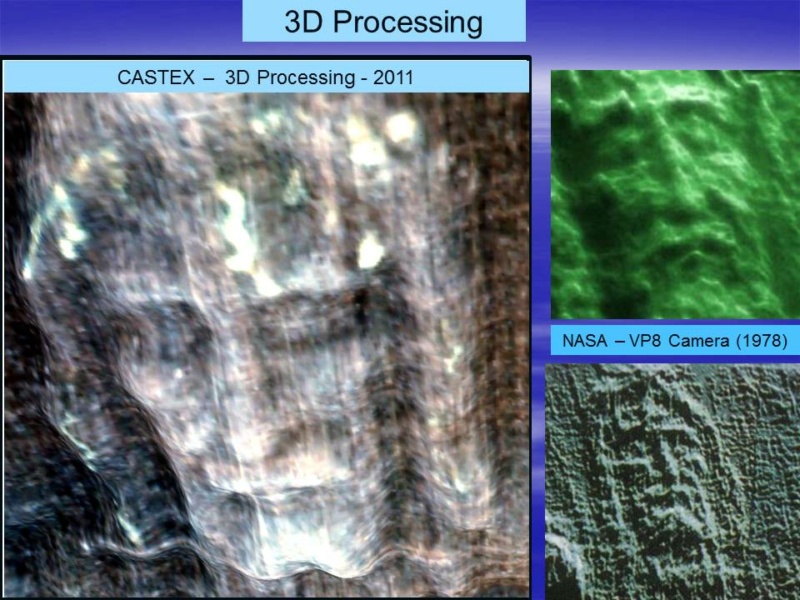

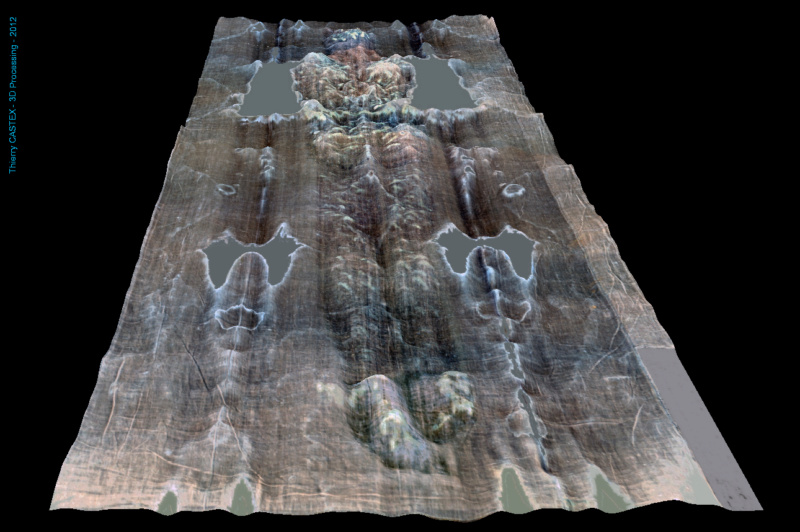

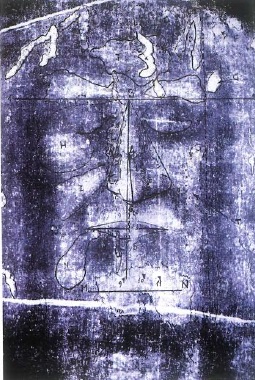

The Shroud is the empirical link to the gospels, confirming all the narratives as true. Discovered to be photonegative in 1898 by Secondo Pia, the negative of the Shroud's image revealed a more distinct and detailed view of the man's face and body, enhancing the realism and depth of the figure. Further intrigue was added in 1976 when analysis with a VP-8 Image Analyzer revealed encoded 3D information in the Shroud's image, unlike any conventional 2D image, indicating a unique image formation process. And now, using modern advanced AI tools, Otangelo Grasso was able to get a very close realistic image of how the man on the Shroud that many believe to be Jesus looked like in real life.

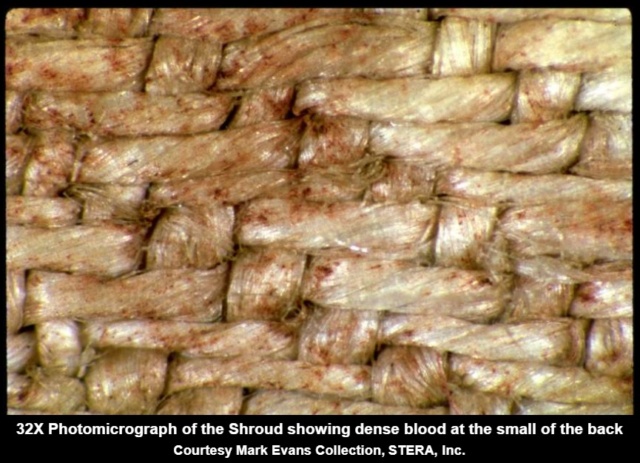

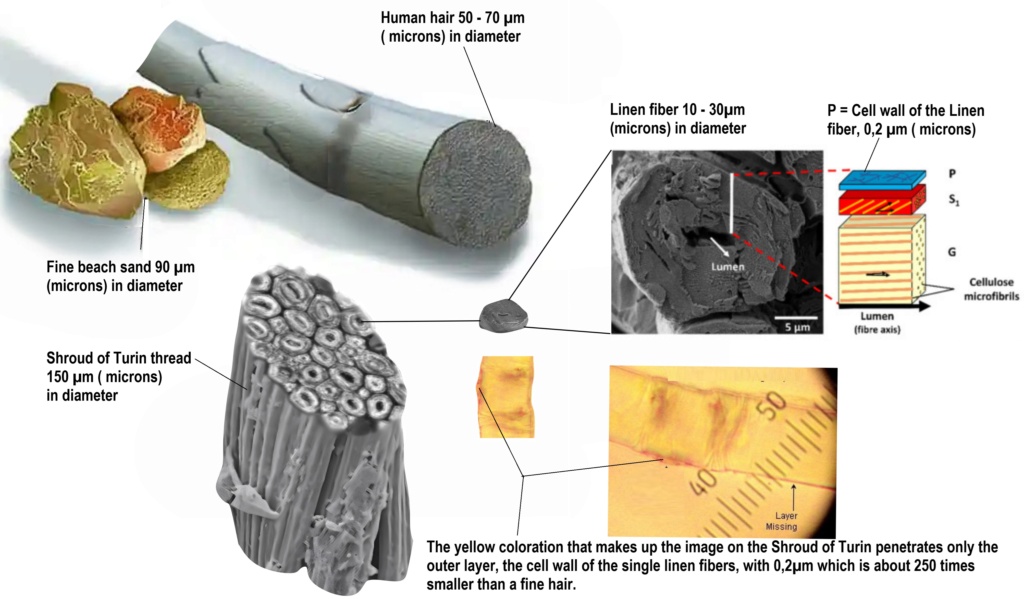

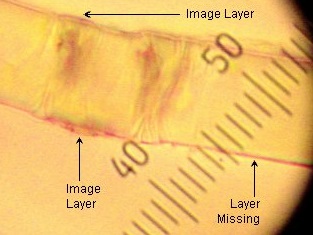

The photonegative, and 3D characteristic strengthens the case for the authenticity of the Shroud. Pollen grains found on the Shroud have been traced to plants native to the regions around Jerusalem, lending geographical credibility to its origins. The weave and textile patterns of the linen cloth are consistent with materials available in the first century, aligning with the historical period of Jesus's life and death. The bloodstains on the Shroud have been analyzed and identified as type AB, with properties consistent with genuine human blood, containing traces of bilirubin, a compound produced by the human body in response to severe torture. The image on the Shroud resides on the utmost surface of the linen cloth, and investigations by the Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP) confirmed it is not a painting, adding to its enigma.

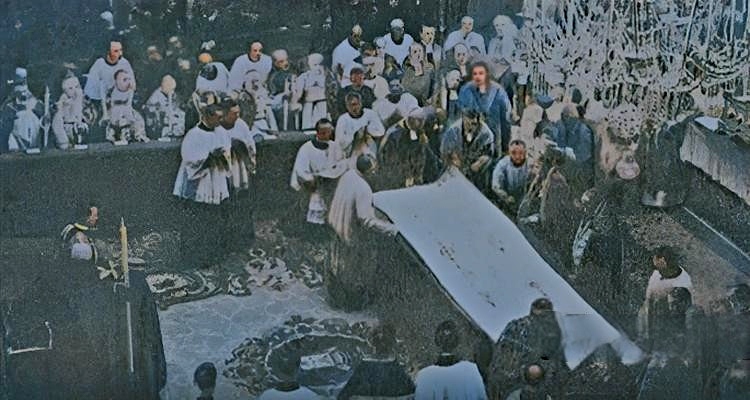

In November 2022, I visited the Othonia Atheneum Apostolorum Shroud Exposition in Rome. Upon returning home, it struck me that the informational panels I had seen were nearly two decades old, dating back to 2005. Considering the advancements and discoveries made in the scientific study of the Shroud since then, I felt a compelling need to update these materials. Motivated by the significant developments in understanding the Shroud's imagery, I embarked on a project to create a new series of infographics. These were designed to be more visually driven and less reliant on text, reflecting the latest insights. From December 2023 to January 2024, I crafted 20 such infographics and compiled comprehensive background information to support each panel. This endeavor culminated in the creation of a book that presents this updated and enriched perspective on the Shroud.

Chapter 1 Intro and description of the Shroud & History of the Shroud

Chapter 2 6th. to 14th. century of the Shroud

Chapter 3 Secondo Pia's 1898 discovery

Chapter 4 3d Information on the Shroud

Chapter 5 STURP Investigation from 1978

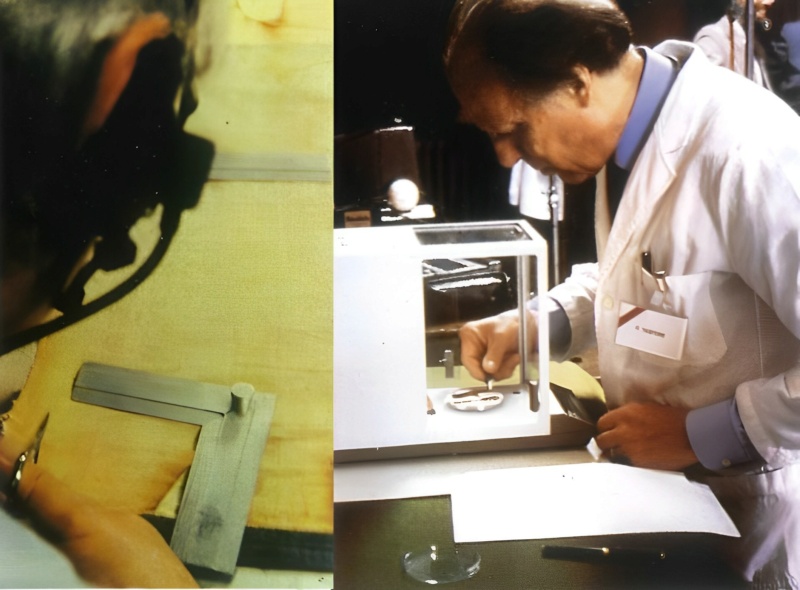

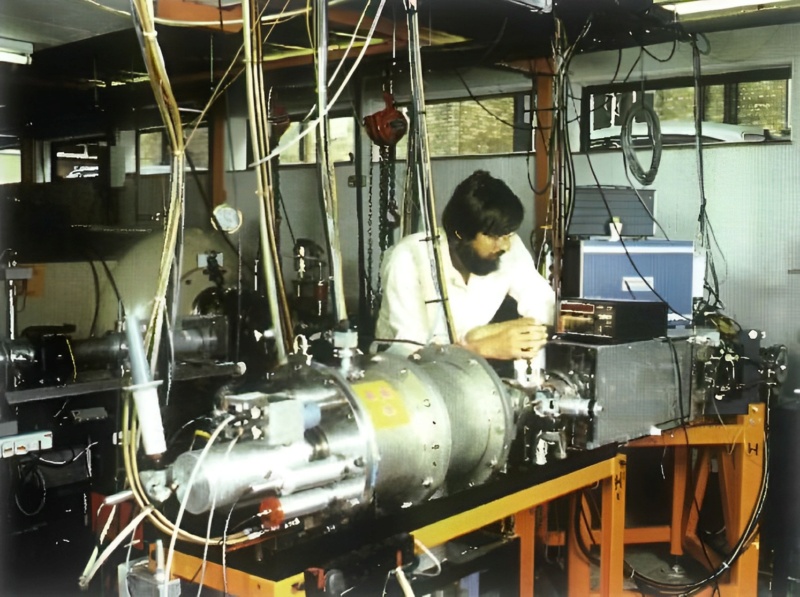

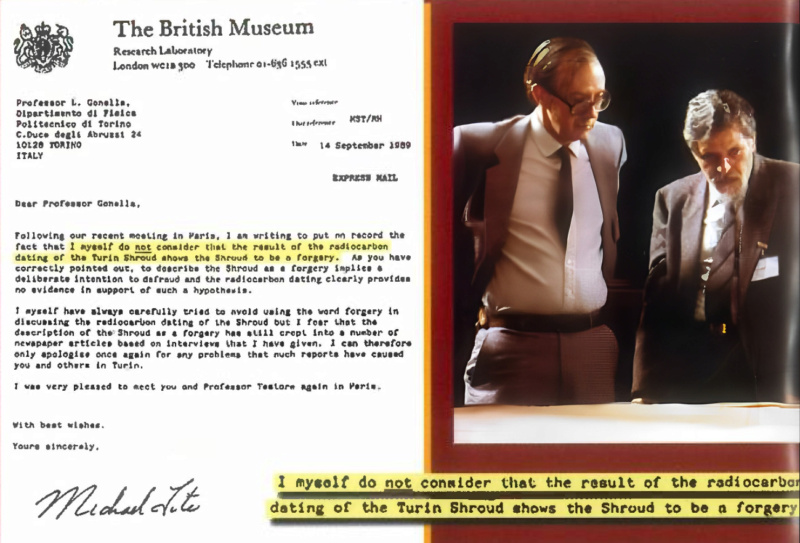

Chapter 6 The Radiocarbon dating

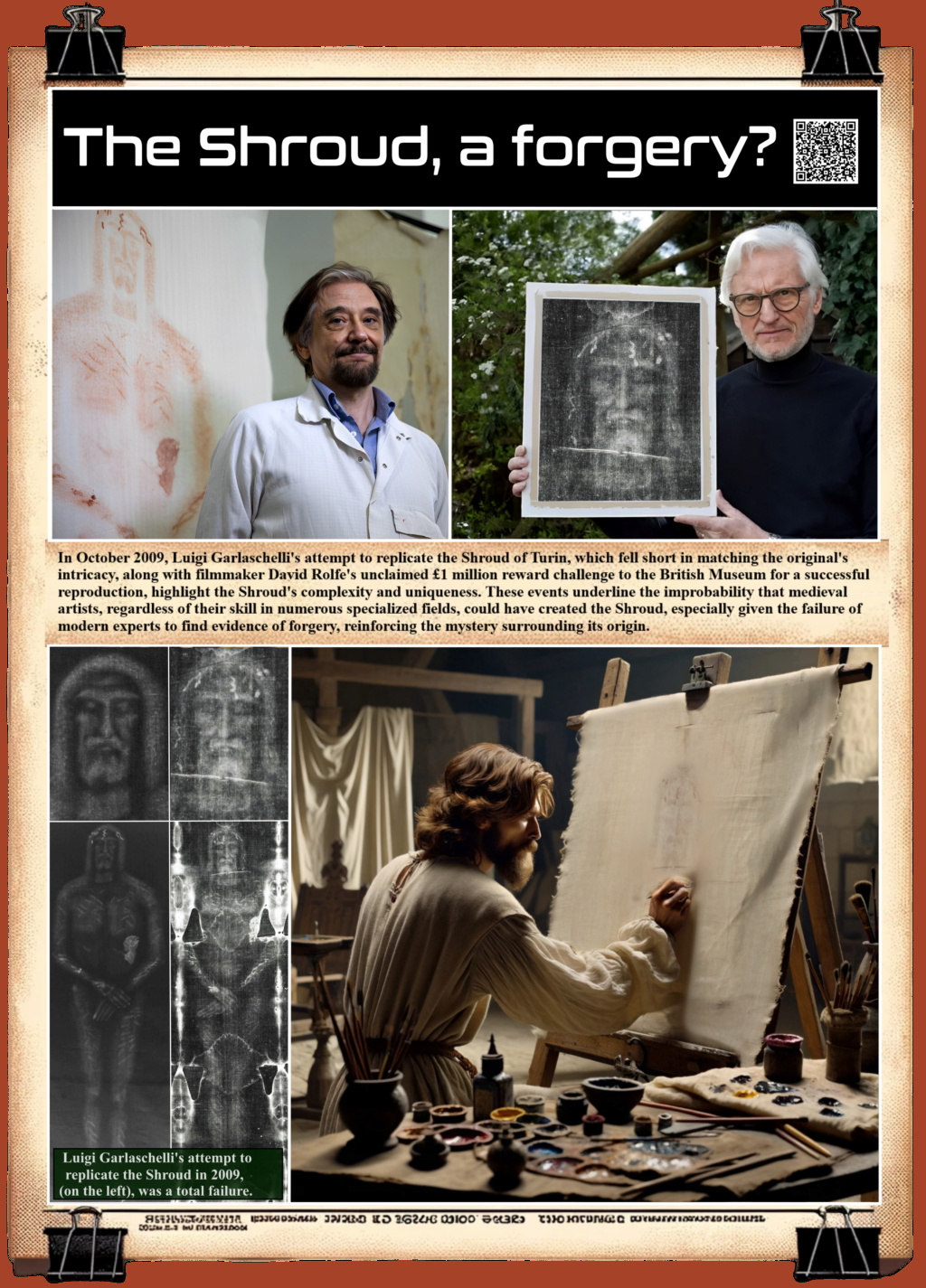

Chapter 7 The Shroud, a forgery?

Chapter 8 How was the image made?

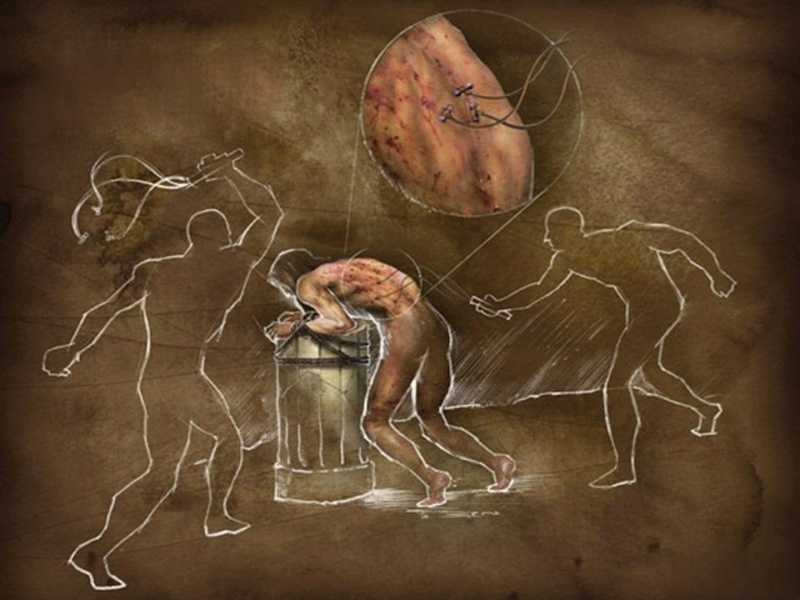

Chapter 9 The Flagellation

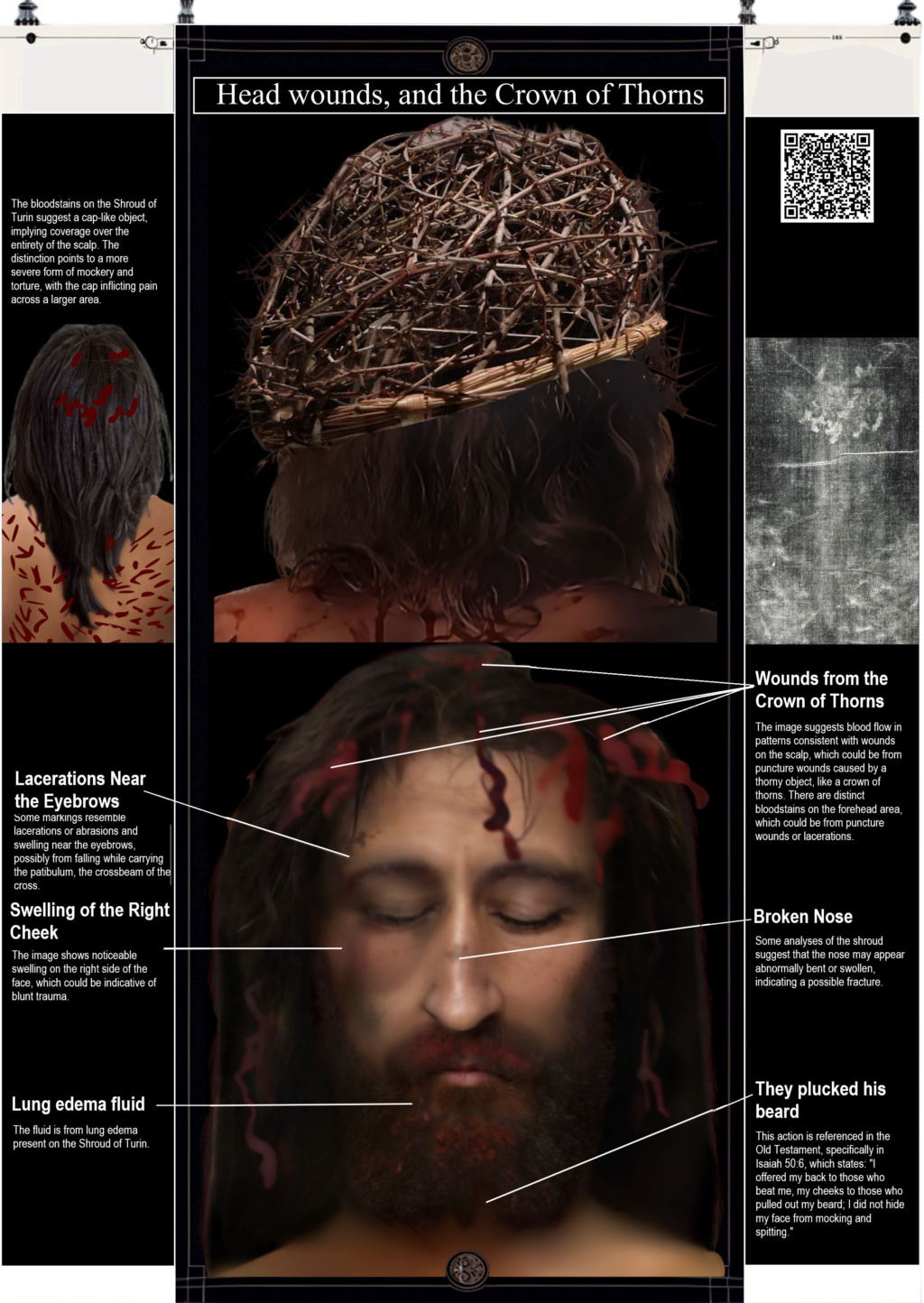

Chapter 10 Head Wounds, and the Crown of Thorns

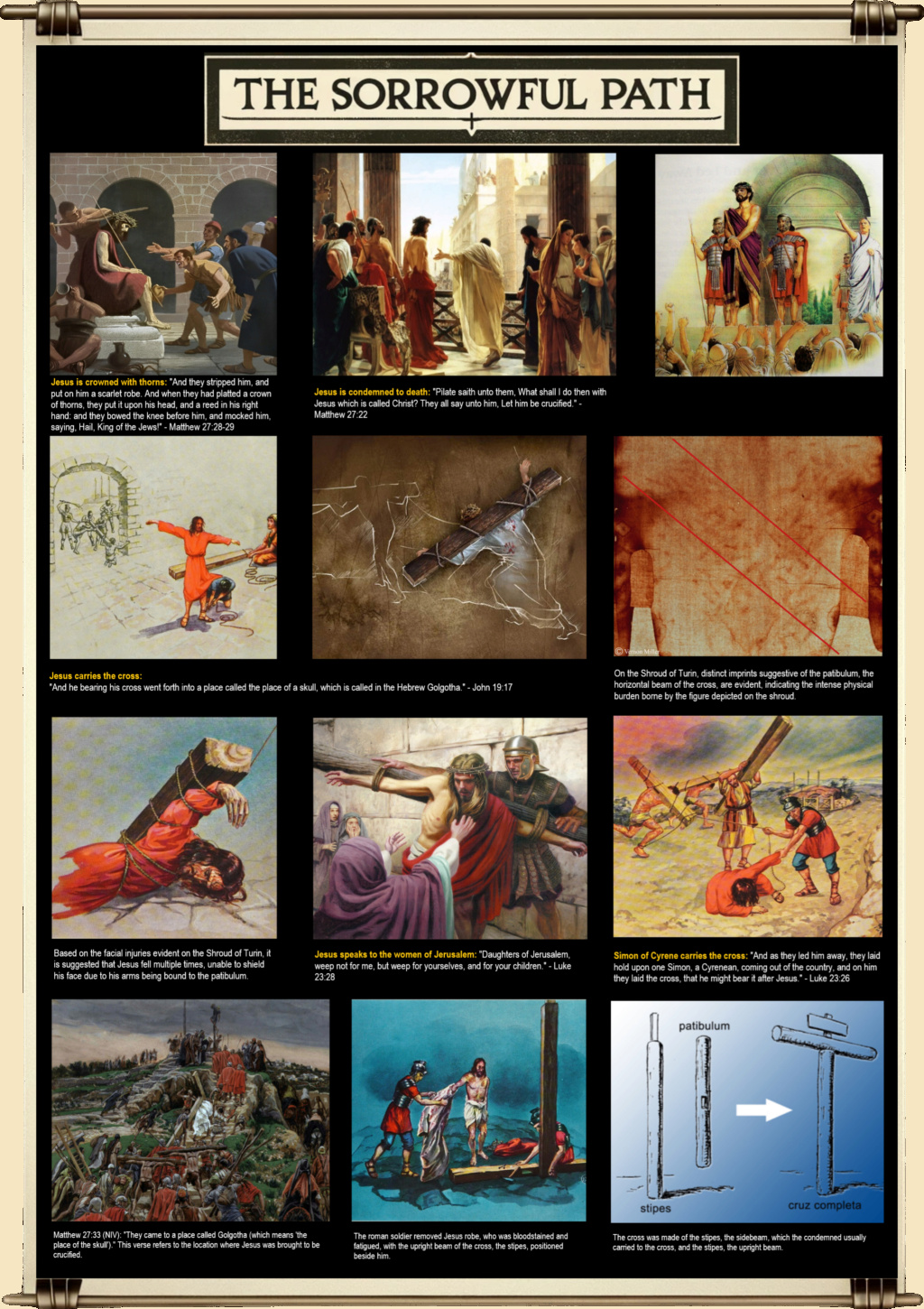

Chapter 11 The Sorrowful Path

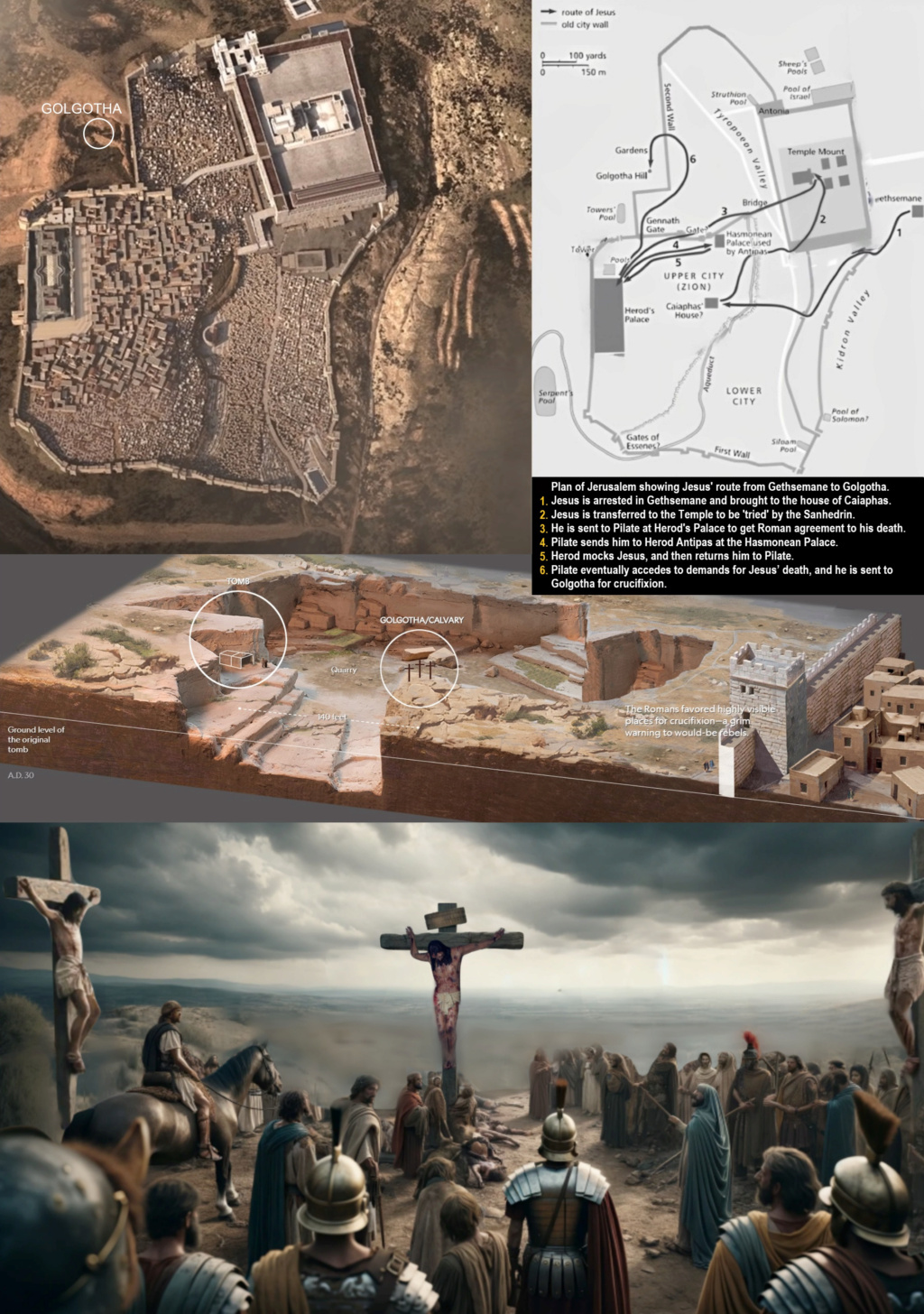

Chapter 12 Golgotha - Calvary - The Crucifixion

Chapter 13 The death

Chapter 14 The burial

Chapter 15 The Resurrection

Chapter 16 The Linen

Chapter 17 The Blood

Chapter 18 Pollen, Limestone, and Micro traces

Chapter 19 Bought, Purchased, Randomed and Redeemed

Chapter 209 Addressing Common Objections about the Shroud & Some Renderings & Images

Chapter 1

What is the Shroud of Turin?

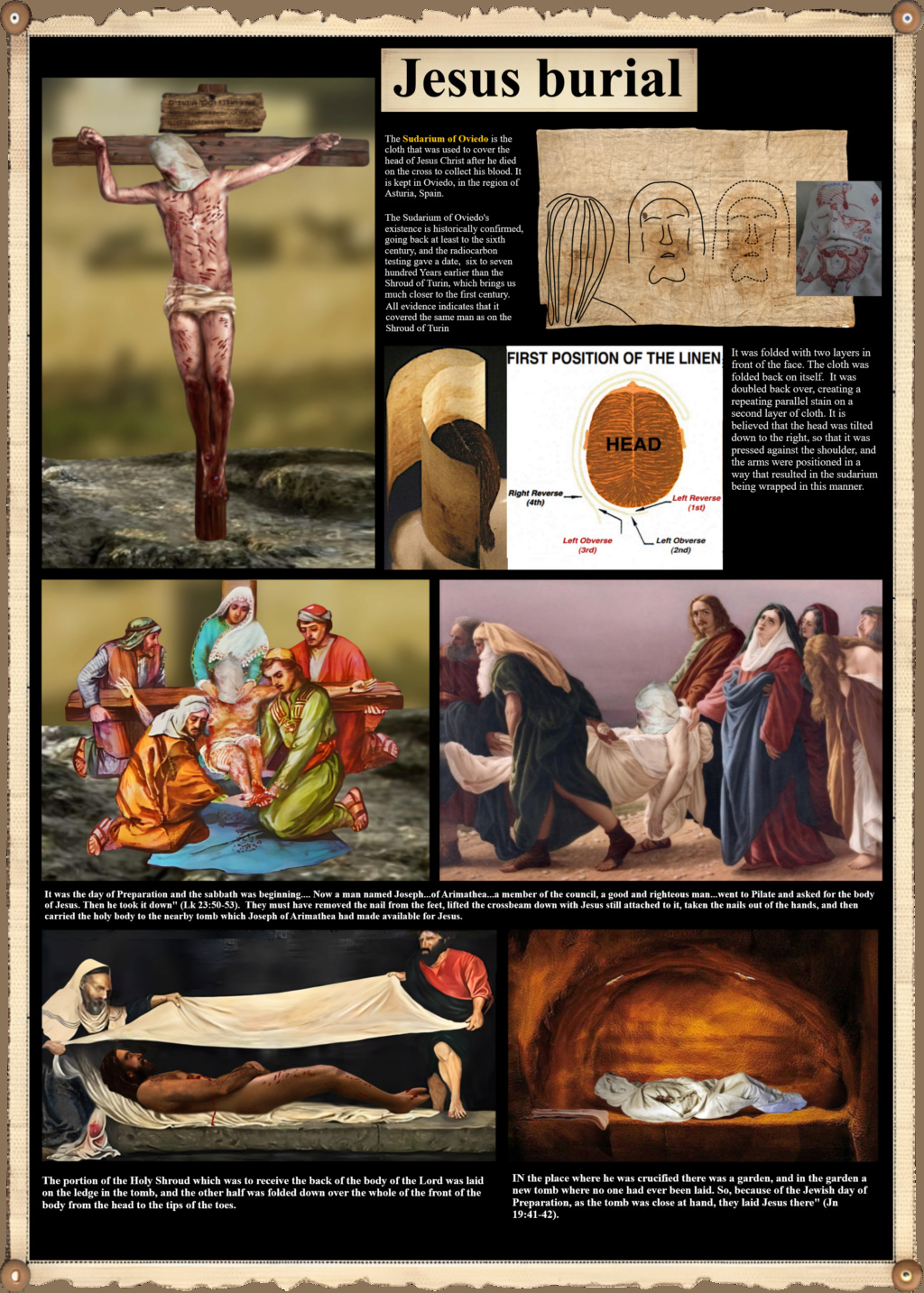

Bible References To The Burial Shroud Of Jesus

1. Matthew 27:59

And Joseph took the body and wrapped it in a clean linen shroud

2. Mark 15:46

And Joseph bought a linen shroud, and taking him down, wrapped him in the linen shroud and laid him in a tomb that had been cut out of the rock. And he rolled a stone against the entrance of the tomb.

3. Luke 23:53

Then he took it down and wrapped it in a linen shroud and laid him in a tomb cut in stone, where no one had ever yet been laid.

4. John 19:40

So they took the body of Jesus and bound it in linen cloths with the spices, as is the burial custom of the Jews.

5. John 20:5

And stooping to look in, he saw the linen cloths lying there, but he did not go in.

6. John 20:6

Then Simon Peter came, following him, and went into the tomb. He saw the linen cloths lying there,

7. John 20:7

and the face cloth, which had been on Jesus' head, not lying with the linen cloths but folded up in a place by itself.

The Shroud of Jesus presents an image that captures a pivotal moment, the most important event in human history: the resurrection of Christ. It acts as a physical validation of the narratives found in the New Testament, underscoring the veracity of the teachings and prophecies of both the Old and New Testaments concerning the Messiah. This remarkable relic is a divine testament, providing tangible evidence of God's power. It is also the receipt of the unfathomably high price paid through the sacrifice made by Christ, shedding his blood on the cross for our sins. Those who investigate and study it will find undeniable evidence that strengthens their faith, alleviates uncertainties, dispels any doubts, and brings hope, joy, and peace into their hearts. We are not alone. The sentiment it evokes affirms the belief that we have a benevolent, loving creator, that has a plan individually for each of us, that extends into all eternity. We are created by Him, to live with Him and to be a part of His family. The purpose of our existence is simple and elegant: To love God, to love others, and to be loved by Him.

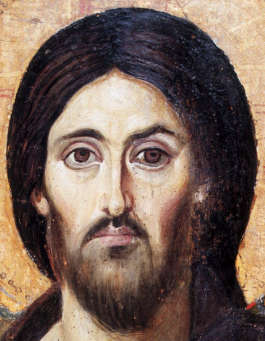

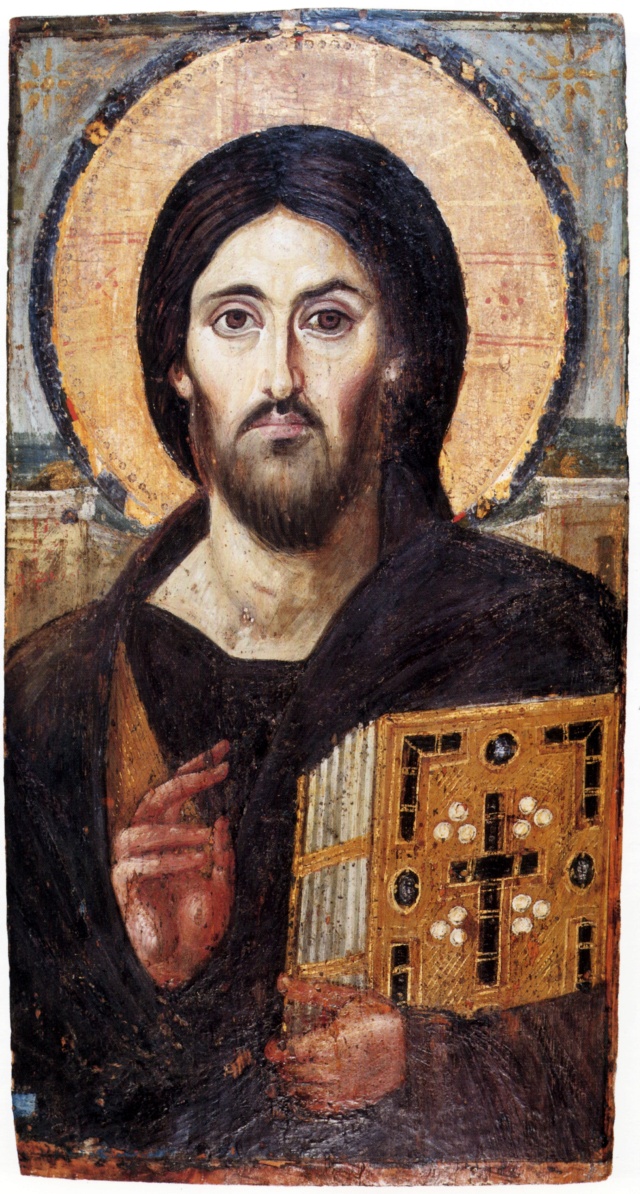

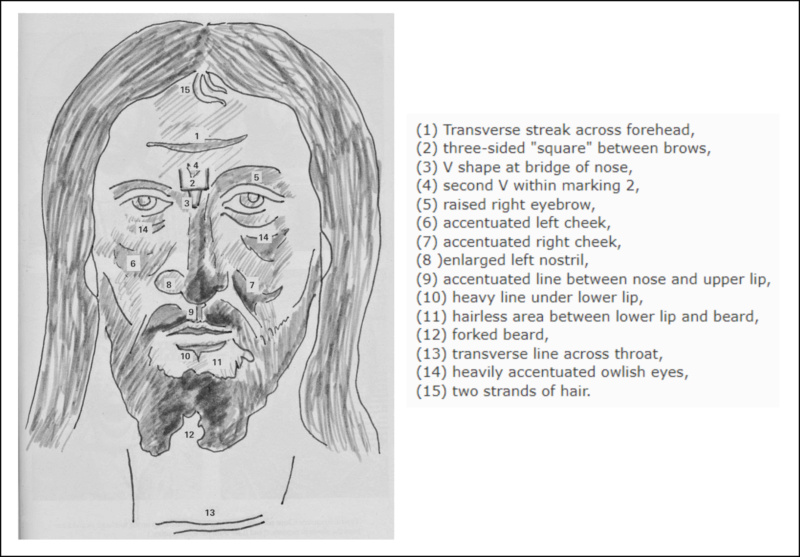

The facial features of the man on the shroud, while indistinct, convey a sense of nobility, Lordship, peace, serenity, and solemnity. The eyes are closed, giving an impression of peace or repose.

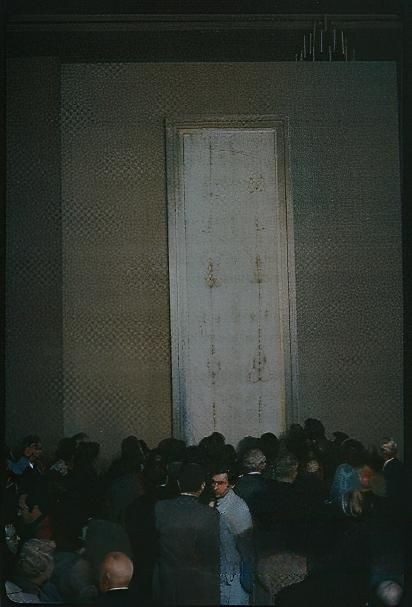

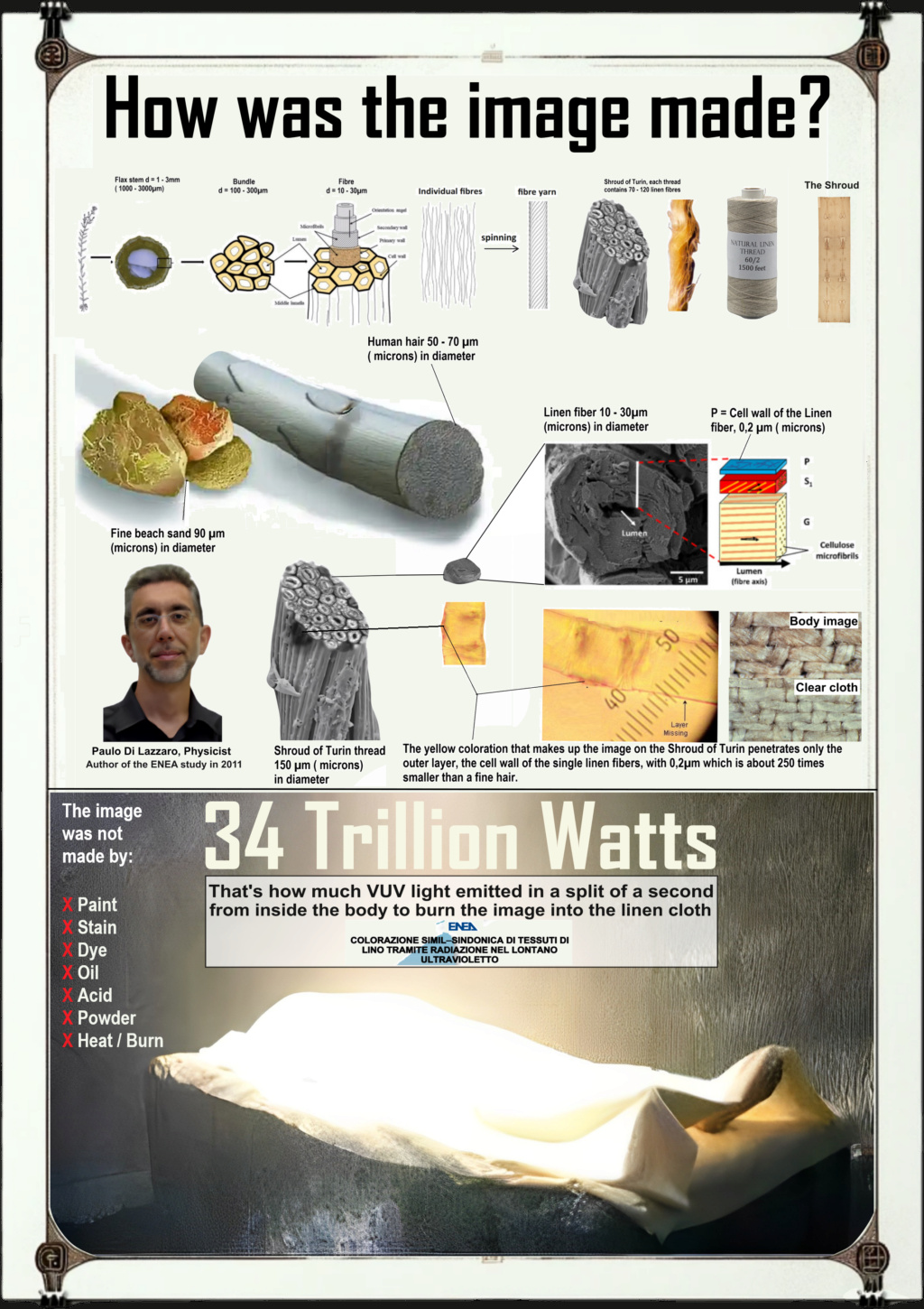

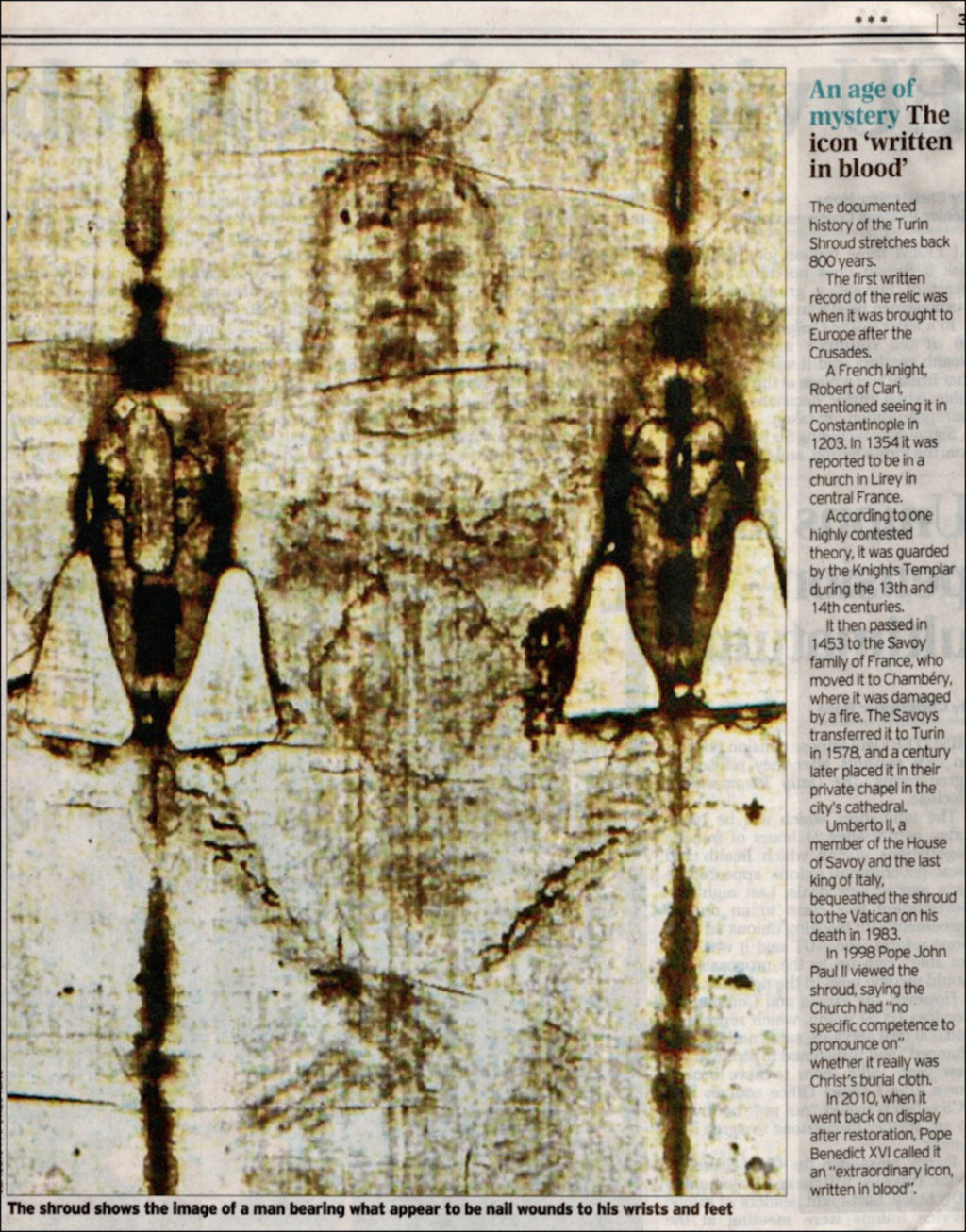

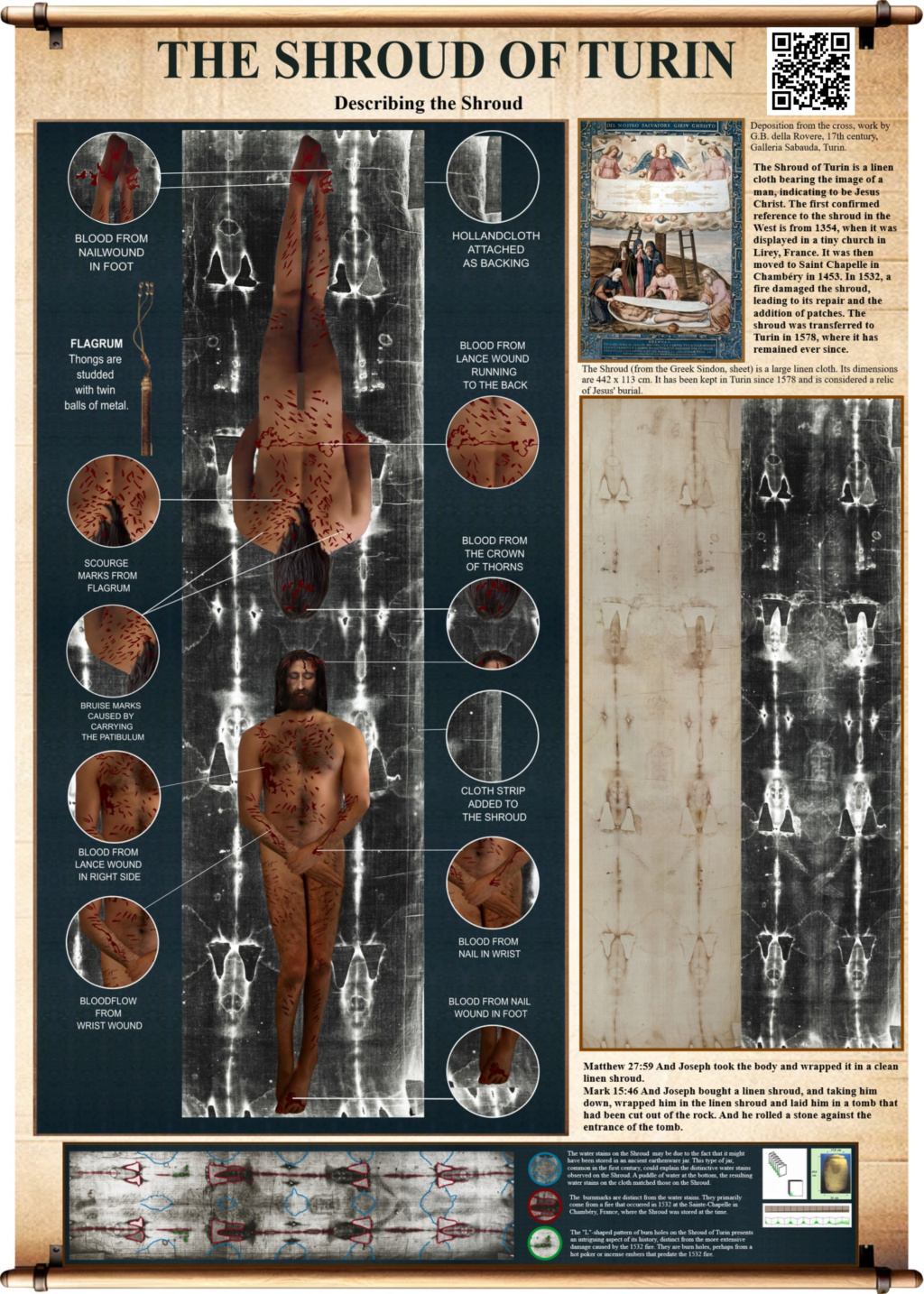

The Shroud, commonly called the Shroud of Turin is a piece of linen cloth that bears the image of a man who has been crucified. It is a rectangular linen cloth measuring approximately 14.3 feet by 3.7 feet and is kept in the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist in Turin, Italy. There is powerful evidence the shroud is the burial cloth of Jesus Christ, that bears his actual image. The image on the shroud appears as a negative image ( like a negative of a photograph) and has most likely been formed by the imprint of the body that had been wrapped in the cloth after death. The Gospels do describe the burial of Jesus in a linen cloth, which is a reference to the shroud. The Gospels describe Joseph of Arimathea taking Jesus' body, wrapping it in a clean linen cloth, and placing it in his tomb (Matthew 27:57-60, Mark 15:46, Luke 23:53). The Gospel of John also mentions the burial cloth, stating that Nicodemus helped Joseph of Arimathea prepare Jesus' body for burial by bringing a mixture of myrrh and aloes. They took Jesus' body, and wrapped it in linen cloths with the spices, according to Jewish burial customs (John 19:38-40). Scientists have inferred that a burst of 34 thousand billion Watts of vacuum-ultraviolet radiation produced a discoloration on the uppermost surface of the Shroud’s fibrils (without scorching it), which gave rise to a perfect three-dimensional negative image of both the frontal and dorsal parts of the body wrapped in it.

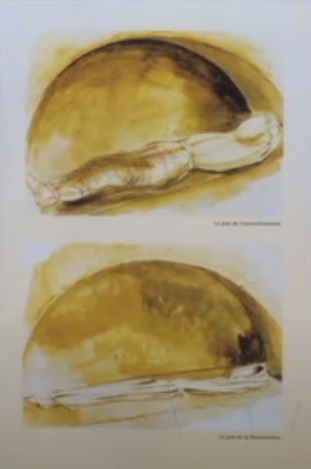

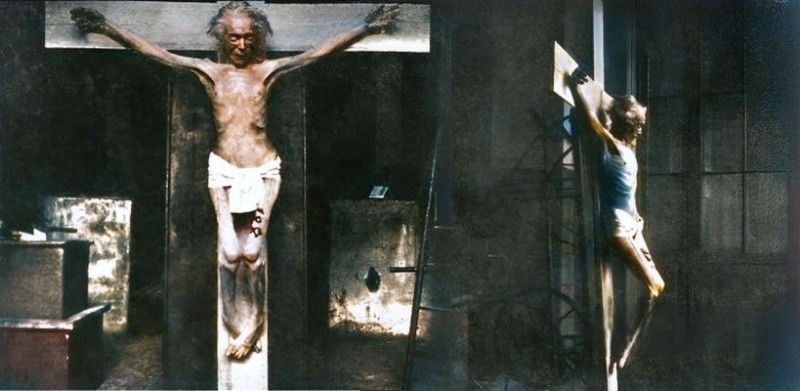

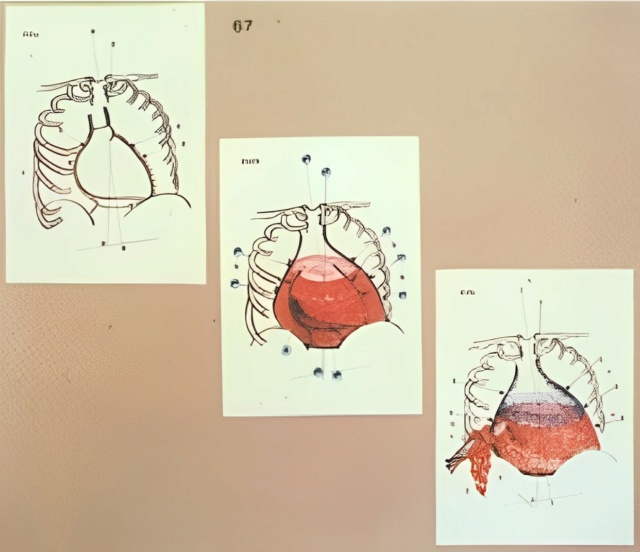

Rigor Mortis and the Crucifixion Imprint

Rigor mortis, the postmortem stiffening of muscles, is a critical forensic marker for determining the time elapsed since death. This process begins within 2 to 6 hours of death, initially affecting smaller muscles such as those in the jaw and neck, before progressing to the larger muscles of the limbs. The condition typically encompasses the entire body within 12 hours and remains for up to 72 hours before the onset of decomposition causes it to dissipate.

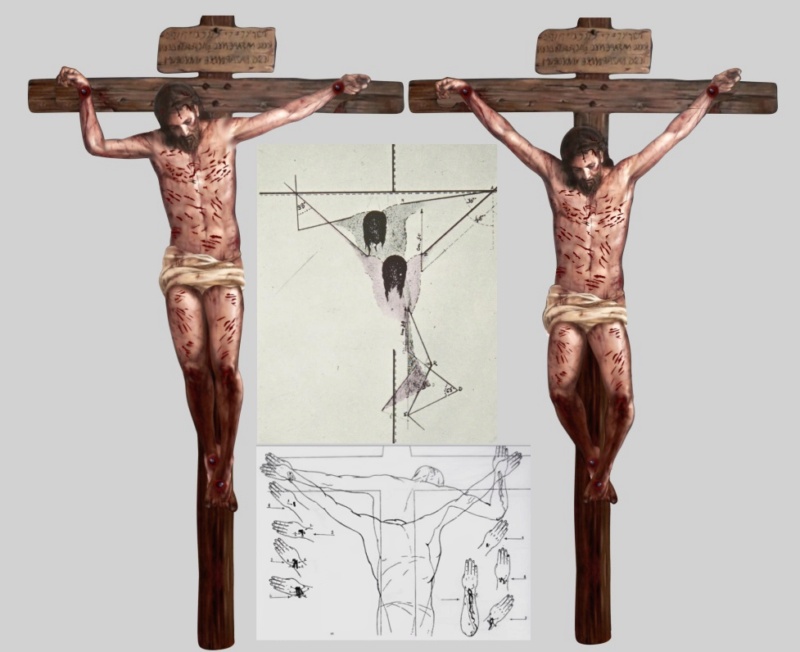

When rigor mortis is observed in the extremities, such as the feet, it signifies that the phenomenon has advanced through its initial stages and reached the lower parts of the body, indicating that a considerable period has passed since the individual's death. This is particularly relevant in forensic analysis when a body is discovered in a position reminiscent of crucifixion. The detection of rigor mortis in the lower limbs not only confirms the passage of time since death but also suggests that the body was maintained in a suspended state for an extended duration postmortem. The body's posture at the time of death can significantly influence the manifestation of rigor mortis. In cases where the body is suspended, the force of gravity may accelerate the stiffening process in the lower limbs. This aspect is crucial for forensic experts as they work to reconstruct the death timeline and understand the circumstances surrounding the individual's final moments. The comprehensive analysis of rigor mortis, along with other postmortem changes such as livor mortis and algor mortis, aids forensic investigators in estimating the postmortem interval more accurately. This thorough examination is essential for a deeper understanding of the events leading to and following death. The Shroud offers a unique case study in this regard. The detailed imprints on the Shroud are consistent with the forensic expectations of a crucified individual, providing insights into the posture and the nature of the wounds. The positioning of the body, as evidenced by the Shroud, aligns with the known effects of crucifixion and subsequent rigor mortis, offering a tangible link to ancient practices and the conditions of the period. This alignment between the Shroud's evidence and forensic science underscores the value of interdisciplinary studies in uncovering historical truths, further enriching our understanding of significant historical events and figures.

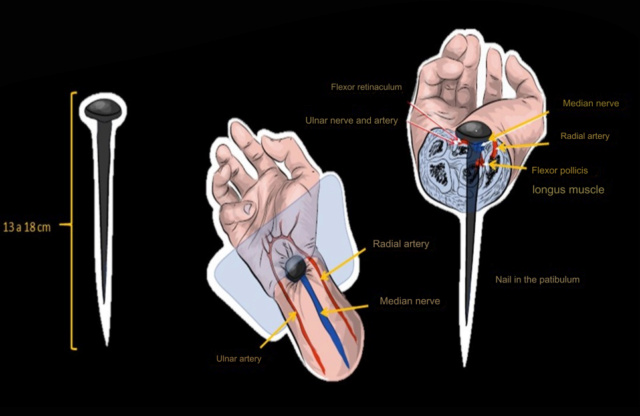

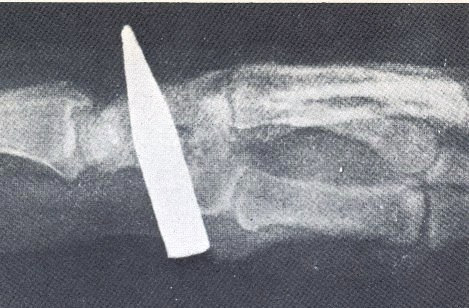

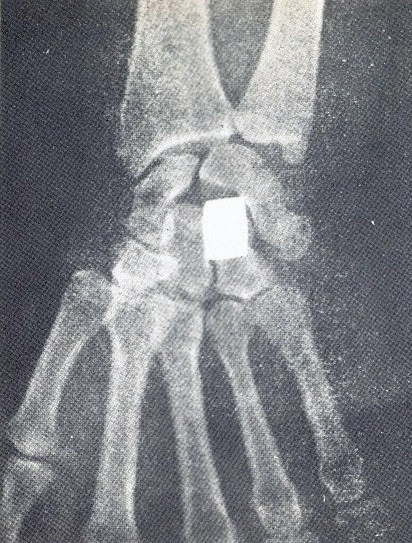

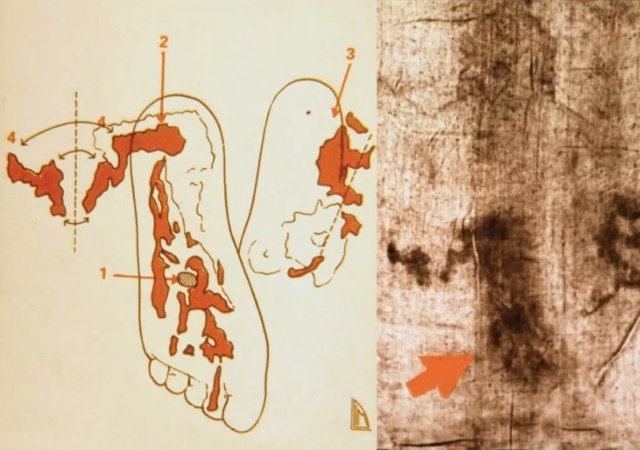

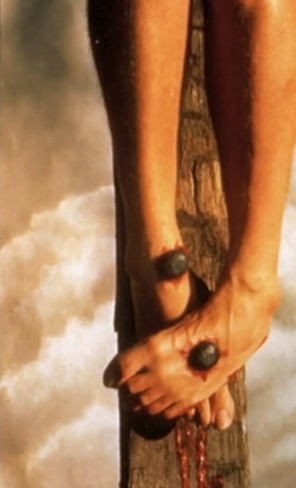

Crucifixion Mechanics and the Certainty of Death

The method of crucifixion, a historical execution practice, is characterized by its excruciating and prolonged nature. The positioning and nailing of the feet played a significant role in the victim's ability to prolong life during this agonizing process. The use of two nails for one foot and a single nail for the other was not merely a matter of convenience or cruelty; it served a specific purpose in the mechanics of crucifixion. This arrangement allowed for one foot to have a limited range of movement, enabling the victim to alternately push up to breathe and then relax, a cycle that could be sustained only while the victim remained alive. This ability to push up was crucial for the victim to stave off asphyxiation, as the crucifixion posture severely impeded normal respiration. The cessation of this movement was a clear indicator of death. Observers, particularly the Roman soldiers tasked with carrying out and overseeing executions, were well-versed in these signs. Their expertise in such matters was critical, given the Roman emphasis on ensuring the death of the condemned. The historical accounts indicating that the soldiers did not feel the need to break Jesus' legs, as was customary to hasten death in crucifixion if the victim was still alive, underscores their certainty of His death. This practice of breaking the legs, known as crurifragium, was a brutal method to induce rapid asphyxiation, ensuring the victim could no longer lift themselves to breathe. The narrative that the soldiers refrained from breaking Jesus' legs due to their confidence in His death aligns with the forensic analysis of crucifixion techniques and the physiological effects on the human body. This congruence between historical descriptions and modern forensic understanding lends support to the authenticity of the accounts of Jesus' death on the cross. Furthermore, the detailed analysis of crucifixion practices, including the specific use of nails in the feet, enriches our comprehension of the historical and physical realities of this form of capital punishment, providing a deeper context to the events described in historical texts.

The 1532 Fire

In 1532, a significant event tested the resilience of the revered cloth: a fire broke out in the church where it was safeguarded. This calamity led to the formation of two distinct scorch lines flanking the central image on both the front and dorsal sides, a testament to the intensity of the flames that threatened its destruction. Additionally, the aftermath of the rescue efforts is marked by water stains, remnants of the urgent attempts to quench the fire and save the cloth by dousing the metal container in which it was stored. The fire's heat, while causing damage, did not alter the image's integrity in a manner consistent with the application of organic compounds. If the image had been the result of such materials, the intense heat would likely have caused a gradation in the discoloration intensity, fading or altering the image in a discernible pattern. However, the absence of such gradation provides compelling evidence against the theory that the image was crafted using organic pigments or dyes. This resilience of the image, despite the exposure to extreme conditions, adds another layer of intrigue to the cloth's history. It suggests that the method of the image's formation is unlike any known artistic or chemical application, supporting the argument for its authenticity. The survival of the image, undistorted by the fire's heat, aligns with the understanding that the image's formation is not merely the result of human craftsmanship but possibly of a profound and mysterious event. The 1532 fire, rather than diminishing the cloth's value, has inadvertently contributed to its historical and scientific examination. The scorch marks and water stains have become part of its unique fingerprint, providing additional data points for researchers. These features offer insights into the cloth's material resilience and the conditions it has endured, further enriching the ongoing dialogue about its origins and the circumstances surrounding the image it bears.

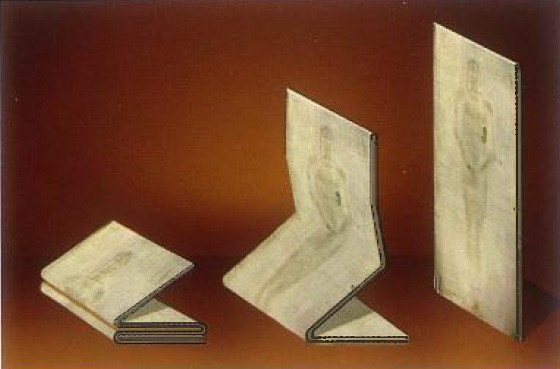

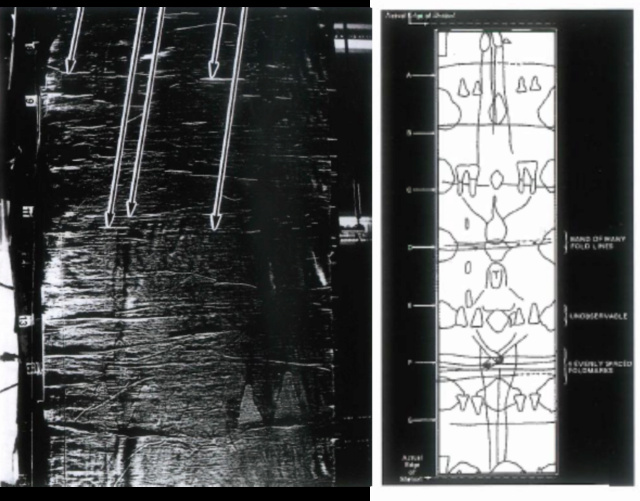

Understanding the Patches and Patterns on the Shroud

In the wake of the 1532 fire, a meticulous effort was undertaken to preserve the integrity of the sacred cloth. The fire's aftermath left parts of the cloth charred, necessitating the removal of the damaged material. These areas were carefully restored with patches, a testament to the dedication to preserving this invaluable artifact for future generations. The distribution of these patches, along with the scorch marks, traces back to the cloth's folded state during the calamity, revealing a pattern that speaks volumes about the event's impact on the cloth. How the cloth was folded meant that a single corner bore the brunt of the fire's damage. This resulted in multiple sections, once unfolded, displaying the need for repair and thus the subsequent placement of patches. The pattern formed by these repairs and the scorch marks provide a unique insight into the cloth's condition at the time of the fire, illustrating how a moment of crisis has become an integral part of its history. The strategic placement of these patches, mirroring the scorch marks, not only served a restorative purpose but also added a new layer to the cloth's rich tapestry of history. Each patch, carefully sewn into place, represents a chapter in the ongoing story of the cloth's survival and reverence through centuries. This pattern of preservation, marked by the alternating patches and scorches, stands as a visible record of the community's dedication to safeguarding the cloth. Furthermore, the meticulous approach to the cloth's preservation, particularly in the aftermath of the fire, underscores the reverence afforded to it, consistent with its perceived authenticity. The care taken to maintain its integrity, despite the challenges posed by the fire, reflects a recognition of its significance beyond mere historical or artistic value. This reverence and the efforts to preserve the cloth in the face of adversity contribute to the ongoing dialogue about its origins, enhancing its mystique and the reverence it commands.

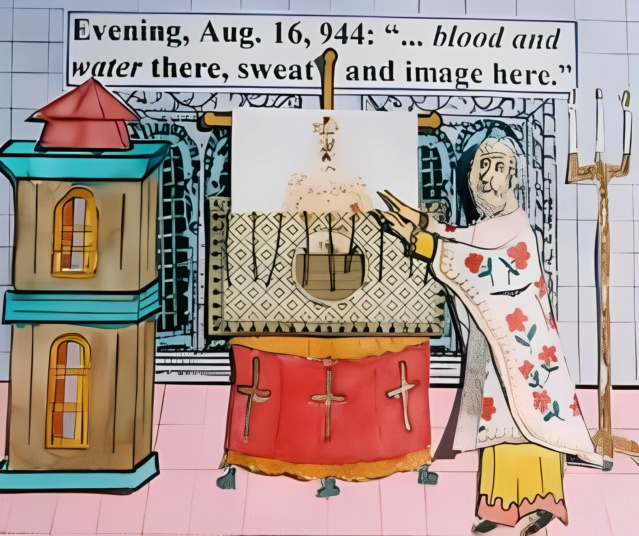

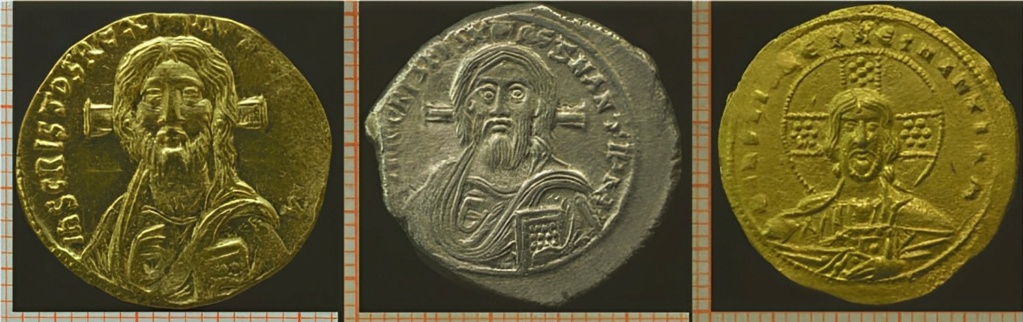

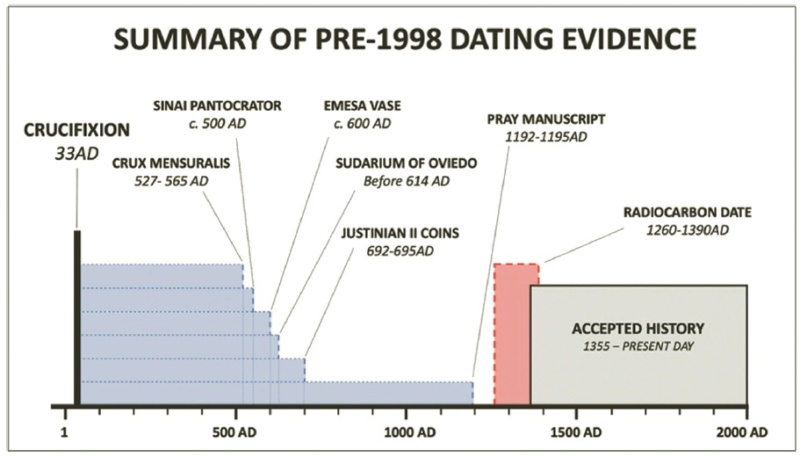

From Edessa to Turin

The Shroud's intricate history is illuminated by the distinctive L-shaped pattern of burn holes, a feature that intriguingly mirrors depictions found in the Hungarian Pray Manuscript, dated between 1192-1195 AD. This correlation is pivotal, as it suggests the Shroud's presence in Constantinople before the city's sacking in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade. The manuscript's depiction predates the commonly cited carbon-14 dating range of 1260 to 1390 AD, thus challenging these results and supporting the Shroud's earlier existence. Historically referred to as the Mandylion, the cloth's journey from Edessa, Turkey, to Constantinople, encapsulates its significance across centuries. Known as the Image of Edessa, its revered status in early Christian history is well-documented, positioning the Shroud as an artifact of profound historical and spiritual import, traceable back beyond 944 AD. This lineage underpins the argument against the carbon-14 dating, proposing that the Shroud's origins are indeed much older. Supporting this standpoint are various dating methodologies that align with a first-century origin. The analysis of the linen's tensile strength and reflectivity, the distinctive stitching patterns akin to those found at Masada, the Shroud's dimensions correlating with ancient measurements, the historical context of crucifixion practices, and the presence of a Roman Lepton coin dating to the era of 27-30 AD, collectively suggest an earlier date for the Shroud. These elements not only challenge the carbon-14 dating but also enrich the narrative of the Shroud's authenticity and its historical journey. The discrepancies in carbon dating have prompted alternative hypotheses, such as the possibility of an invisible reweaving or the impact of neutron absorption on the linen's nitrogen content, which could skew the carbon dating results. These theories, set against the backdrop of the Shroud's storied past, invite a reevaluation of its dating and further investigation into its origins. As scholars and enthusiasts gather to delve into these complexities, the conference will serve as a forum for robust discussion on the Shroud's dating, exploring the myriad of evidence and perspectives that surround this enigmatic artifact. The dialogue promises to shed light on the Shroud's historical journey, from its origins in Edessa to its current resting place in Turin, offering insights into its enduring significance and the mysteries that continue to envelop it.

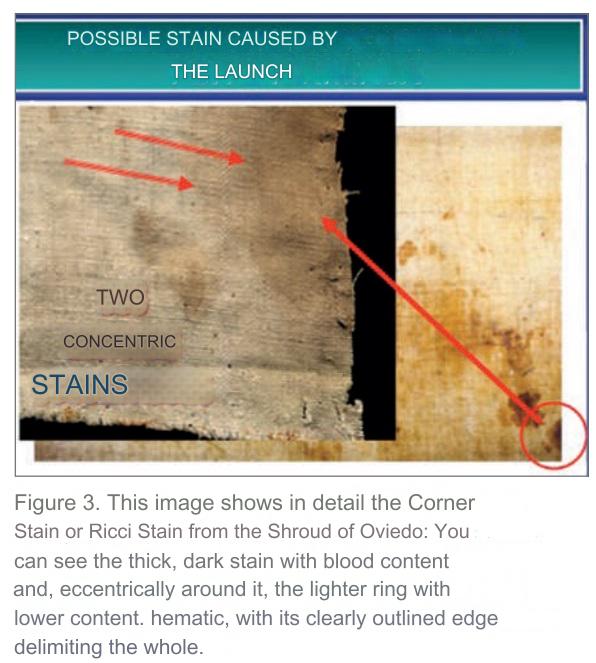

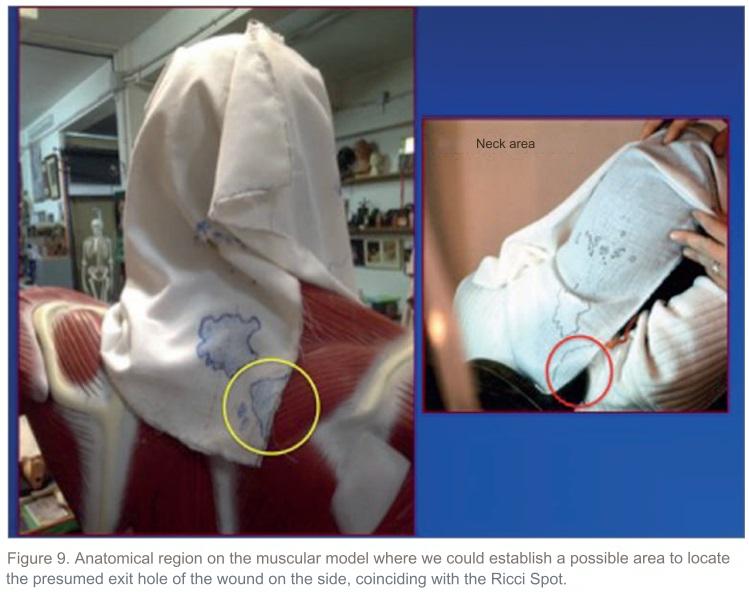

The Forensic Testimony of the Shroud

The dorsal image of the Shroud reveals a compelling detail in the form of separated blood and clear serum emanating from the side wound, a feature that corroborates the biblical account of the crucifixion. This separation is a significant forensic clue, indicating that the heart had ceased its function long enough for the red blood cells to settle, a process that occurs postmortem. This detail not only aligns with the historical practice of crucifixion but also with the specific account of the piercing of Jesus' side, as described in the Gospel of John, where "blood and water" were observed to flow out. This alignment between the Shroud's markings and the biblical narrative is striking, offering a tangible link to the events described in the scriptures. The presence of both blood components on the Shroud suggests a level of physiological realism that adds depth to its authenticity. In the context of crucifixion, the occurrence of such a wound after death would not induce a typical bleeding response but rather a separation of blood components, mirroring the description found in John 19:34. The correlation of this detail with the scriptural account provides a nuanced layer of verification to the events surrounding the crucifixion. It serves as a bridge between the physical evidence present on the Shroud and the spiritual testimony found in the Bible, reinforcing the historicity of the narrative. This confluence of forensic evidence and scriptural description enriches the dialogue surrounding the Shroud, inviting a deeper reflection on its significance and the events it purports to document. This forensic detail, when considered alongside the broader context of the Shroud's imagery and historical journey, contributes to a multidimensional understanding of the artifact. It underscores the potential of the Shroud to serve as a focal point for interdisciplinary study, bridging the realms of science, history, and theology.

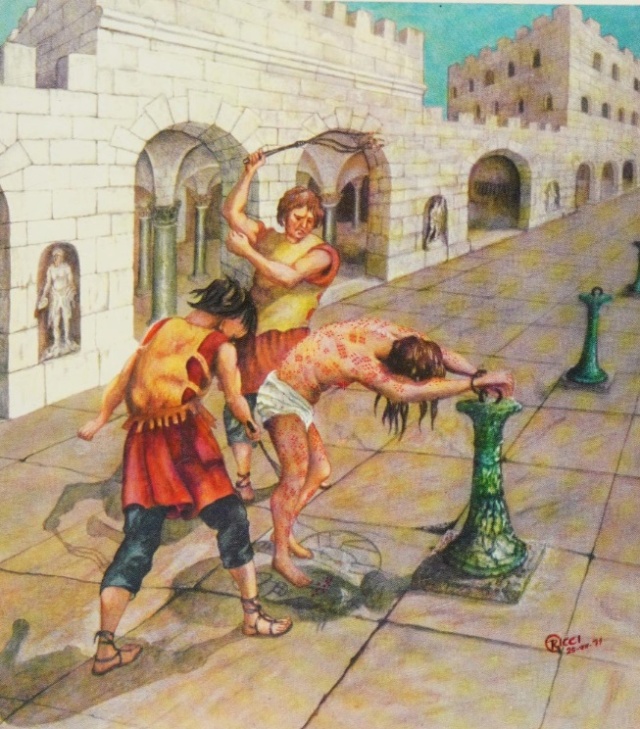

The Marks of Sacrifice

The detailed examination of the scourge marks evident on the cloth reveals a harrowing narrative of suffering, aligned with the historical practices of Roman punishment. Between 100 to 120 scourge marks, consistent with the brutal application of Roman flagrums, are visible across the fabric. These flagrums, typically fitted with dumbbell-shaped weights at the ends of their leather straps, were designed to inflict maximum pain and damage, a fact that the pattern of wounds on the cloth attests to. The distribution of these marks, emanating from both sides, suggests a methodical approach by two executioners, each delivering blows from different angles. What is particularly remarkable about these wounds is the presence of blood serum halos that encircle the dried blood exudates, a detail only discernible under ultraviolet light. This phenomenon indicates that after the infliction of the wounds, blood seeped out, and as the red blood cells coagulated to form the central clot, the clearer serum separated and spread outwards, creating a distinct ring. This subtle but significant detail underscores the authenticity of the wounds represented on the cloth, as it reflects a natural physiological response to severe lacerations. The presence of these serum rings adds a layer of forensic credibility to the cloth, suggesting that the depiction of wounds is not merely artistic but bears the hallmarks of genuine bodily injury. This physiological accuracy reinforces the proposition that the cloth is an authentic burial shroud, bearing the true imprints of a crucified individual. The correlation of these scourge marks with historical accounts of Roman flagellation practices provides a tangible link to the period and manner of execution. This congruence between the physical evidence on the cloth and the historical context of Roman crucifixion methods further solidifies the argument for the cloth's authenticity.

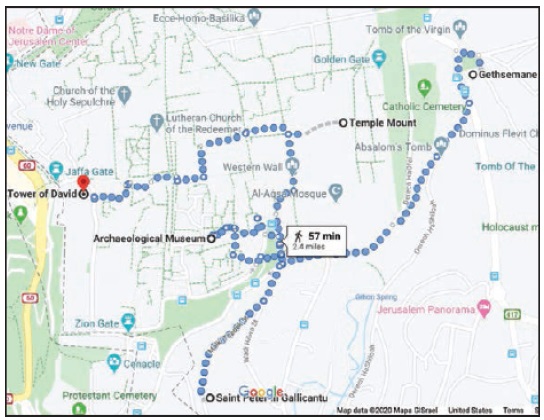

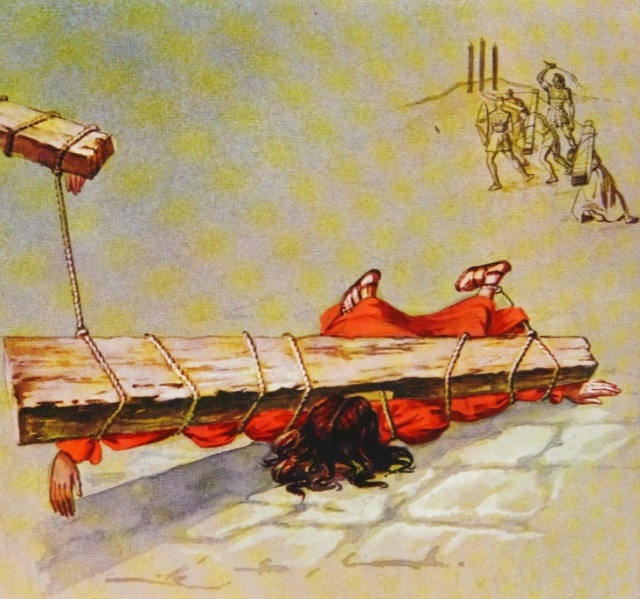

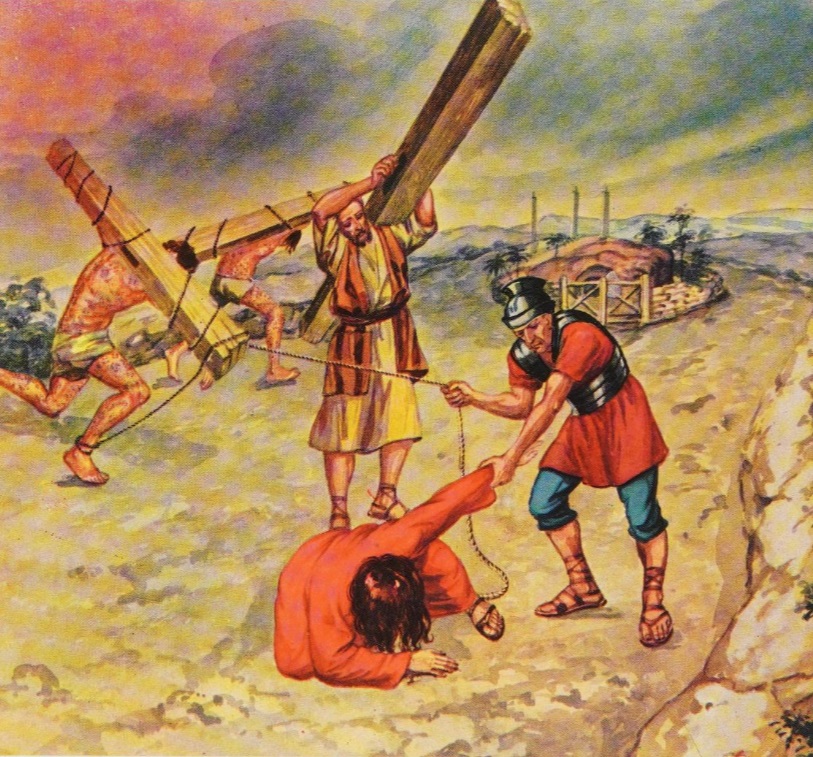

The Burden of the Cross

The cloth bears silent testimony to a journey of immense suffering, as evidenced by the abrasions on both shoulders. These marks are consistent with the harsh impact of carrying a heavy, rough object across a significant distance. This physical burden, as imprinted on the cloth, aligns with the historical account of Jesus bearing his cross to the site of the crucifixion, as described in John 19:17. It is widely understood that the cross referred to in this passage denotes the horizontal beam, or patibulum, which the condemned were often required to carry to the place of execution, where the vertical stake would have already been erected. The presence of these abrasions on the cloth provides a tangible connection to the narrative of the Passion, offering a forensic detail that corroborates the biblical account. The specificity of these marks, located precisely where the patibulum would have rested and caused friction against the skin while being carried, underscores the authenticity of the cloth as a true burial shroud of a crucified individual. This detail adds a layer of historical and physical realism to the narrative, grounding it in the tangible reality of Roman execution methods. Moreover, the abrasions suggest a level of detail and physiological accuracy that transcends mere artistic representation. They reflect a genuine human experience of pain and endurance, captured in the fabric's weave. This confluence of historical, scriptural, and forensic evidence enhances the argument for the cloth's authenticity, providing a multifaceted perspective on the events it is believed to represent.

Crown of Thorns

The cloth meticulously records the echoes of a brutal act, with puncture wounds visible on both the front and back of the head area. These wounds are consistent with injuries that would be sustained from a sharp, thorn-like object being forcibly applied to the scalp. This evidence aligns with the biblical accounts of the crown of thorns placed upon Jesus' head and subsequently beaten into place with rods, as detailed in Matthew 27:30 and Mark 15:17-19. The presence of these puncture wounds on the cloth serves as a poignant physical testament to the narrative of suffering and humiliation described in the scriptures. The detailed imprints of these wounds on the cloth go beyond mere artistic depiction, suggesting a level of authenticity and specificity that points to a real event. The distribution and nature of these wounds correspond with the crown of thorns' description, reinforcing the cloth's role as a genuine burial shroud of a crucified individual. This correlation between the physical evidence on the cloth and the scriptural descriptions provides a tangible link to the historical events of the crucifixion. Furthermore, the forensic analysis of these wounds offers insights into the nature of the object used and the severity of the act. The wounds suggest a cap-like application of thorns, pressed and beaten into the scalp, causing multiple, deep puncture wounds. This brutal act, captured in the fabric of the cloth, echoes the scriptural accounts of mockery and torture, providing a stark visual representation of the suffering endured. The examination of these wounds within the context of the cloth's wider narrative invites a deeper contemplation of the events leading up to and including the crucifixion. It bridges the gap between historical record and spiritual reflection, offering a visceral insight into the physical realities of the Passion. As such, the cloth stands as a profound artifact, not only of historical significance but also as a focal point for theological and meditative reflection on the depth of suffering and sacrifice embodied in the crucifixion narrative.

Pollen Imprints

The cloth harbors microscopic witnesses to its geographic and historical journey, notably through the presence of pollen grains. Among these, specific pollen types unique to the region surrounding Jerusalem stand out, embedding the cloth within a distinct geographic context. This botanical signature provides a tangible link to the land and the natural environment of the area, further grounding the cloth in a real-world setting that aligns with the historical narratives. Remarkably, pollen from a plant characterized by long thorns has been identified in the vicinity of the head imprints on the cloth. This detail is particularly significant given the biblical accounts of the crown of thorns placed upon Jesus' head. The correlation between the presence of this specific type of pollen and the scriptural description of the crown of thorns adds a layer of authenticity to the cloth. It suggests not only a geographical alignment with the historical setting of Jerusalem but also a direct connection to the events described in the New Testament. The identification of these pollen types on the cloth is more than a mere botanical curiosity; it represents a forensic bridge to the past, offering clues to the cloth's origins and the events it is believed to depict. This botanical evidence supports the notion that the cloth was present in the Jerusalem area during a time consistent with the historical period of the crucifixion. Moreover, the presence of pollen from a thorn-bearing plant around the head area of the cloth resonates deeply with the symbolism and reality of the suffering depicted in the crucifixion narrative. It serves as a silent but potent testament to the authenticity of the events described in the Gospels, reinforcing the physical and historical credibility of the cloth. The integration of botanical forensics with historical and scriptural analysis enriches the multidisciplinary study of the cloth. It opens new avenues for understanding its origins and the profound narrative it carries, bridging the realms of science, history, and theology. As such, the pollen imprints on the cloth not only anchor it within a specific geographical and historical context but also contribute to the ongoing dialogue about its significance and the events it purports to document.

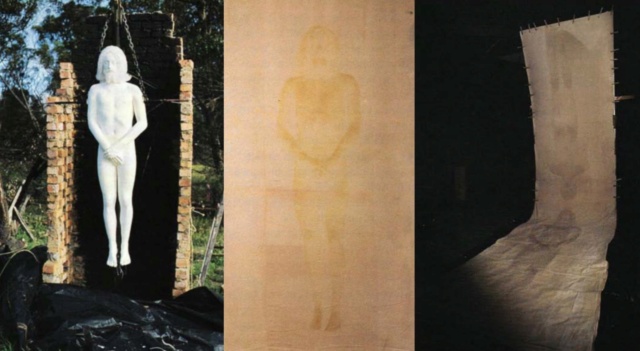

The Mysteries of the Shroud's Images

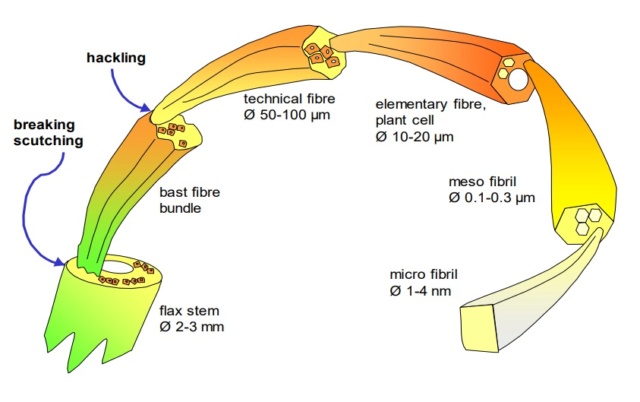

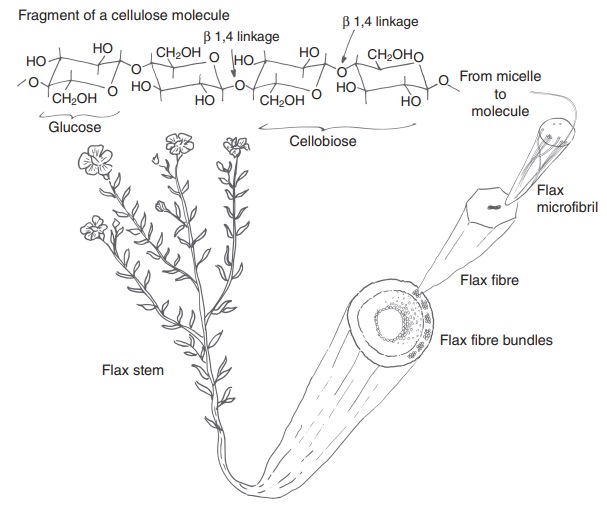

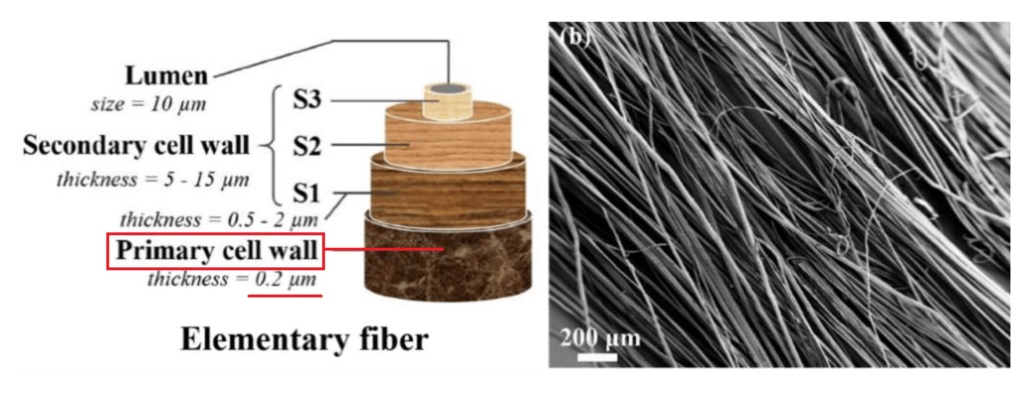

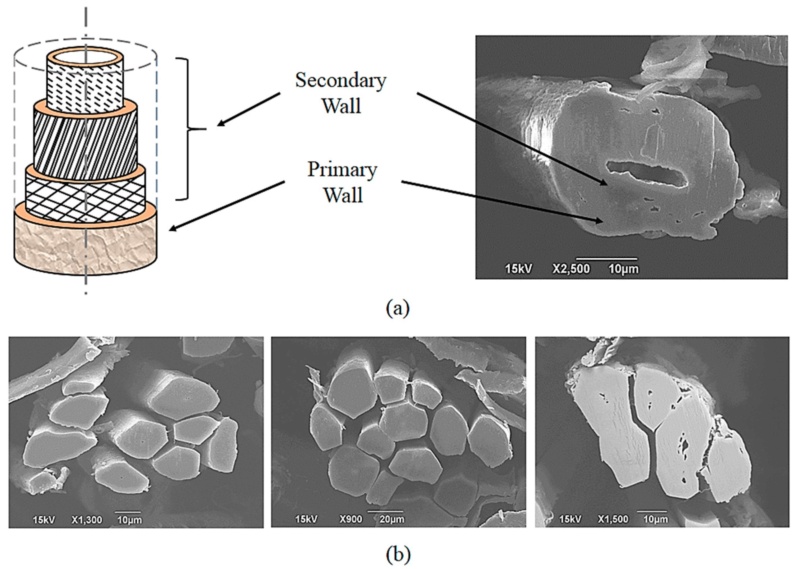

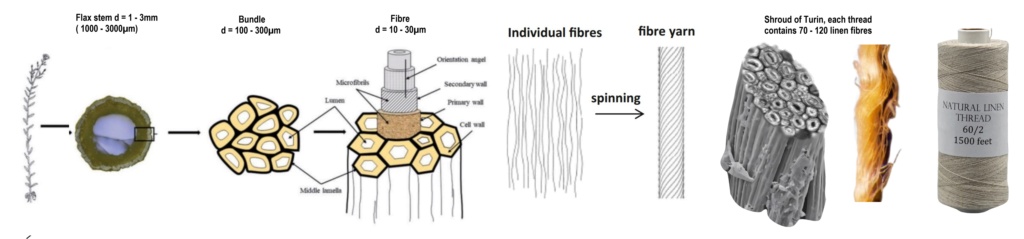

The images on the cloth, both front and dorsal, present a fascinating enigma in the realm of historical artifacts. Not only do these images serve as negative impressions of a crucified man, but they also encapsulate three-dimensional information, akin to a topographical map, that correlates with the distance between the cloth and the body at the time of image formation. This unique feature is not found in any conventional artistic or photographic methods known to date, setting the cloth apart in its singularity. Upon closer examination, the image formation on the cloth is remarkably precise, affecting only the top one or two layers of fibers in each thread, which consists of 100 to 200 fibers. This level of detail extends to the microscopic scale, where the thickness of the discoloration on each fiber is less than 0.4 microns—narrower than a single wavelength of light. Such precision defies the natural capillary action that would occur if the image were created using liquid mediums, as there is no evidence of liquid spreading or soaking between the fibers and threads. The nature of the discoloration itself is indicative of a profound alteration at the molecular level, where the covalent bonds of the carbon atoms within the cellulose molecules of the linen have changed. This alteration, characterized by dehydration and oxidation, is not consistent with any known forms of manual artwork or intentional aging by human hands. The absence of any conventional medium or method that could replicate these intricate details and effects leads to the conclusion that the image could not have been the work of an artist or forger, at any point in history. How the image of a crucified man was imprinted on the cloth, given these distinctive characteristics, remains a subject of intense speculation and inquiry. Theories abound, yet no definitive explanation has emerged that fully accounts for the combination of negative imaging, three-dimensional data content, microscopic precision in discoloration, and the lack of capillary action. This cloth, with its enigmatic imprint, continues to challenge the boundaries of our understanding, inviting scholars, scientists, and theologians alike to ponder its mysteries. As we convene to discuss and delve deeper into these complexities, the conference promises to be a nexus of interdisciplinary exploration. The aim is not only to unravel the scientific and historical underpinnings of the cloth's images but also to contemplate the broader implications of its existence and the profound message it may hold within its fibers.

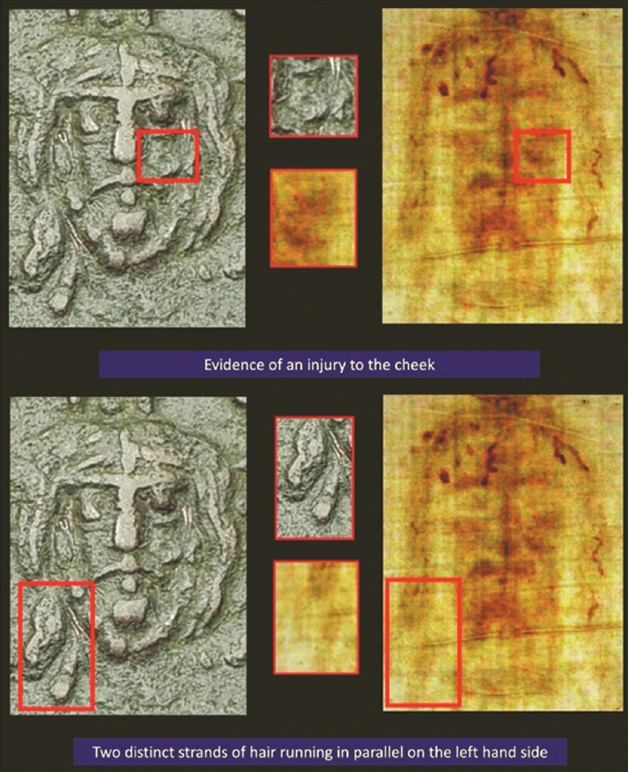

The Facial Features of the man on the Shroud

The cloth presents a haunting portrayal of suffering, with facial features that suggest a harsh physical ordeal. The swollen cheeks and a disfigured nose on the image hint at a severe beating or a traumatic fall, resonating with the biblical accounts of the trials faced during the final hours. The Gospel of John (18:3) alludes to such a beating, while the synoptic narratives in Matthew (27:32) and Mark (15:21) recount the arduous journey to the crucifixion site, during which a fall under the weight of the cross is implied. A closer examination reveals abrasions on the tip of the nose, within which traces of dirt are embedded. This microscopic detail not only underscores the violence of the fall but also situates the event in a gritty, real-world context. The presence of dirt within the wounds adds a layer of authenticity to the image, suggesting that the figure did not merely suffer in a sanitized, abstract sense but interacted with the earth in a moment of vulnerability. The specificity of these injuries, captured on the cloth, transcends mere representation. It offers a tangible connection to the historical figure's final journey, marked by physical suffering and human frailty. The detailed depiction of these facial wounds challenges the notion of an artistically crafted forgery, pointing instead to a genuine imprint of a man who endured significant physical trauma. The correlation between the facial features on the cloth and the scriptural descriptions of the events leading to the crucifixion provides a poignant intersection of history, archaeology, and theology. This confluence invites a deeper reflection on the nature of the suffering depicted and its significance within the broader narrative of the crucifixion. As we gather to explore the mysteries of the cloth, these facial features and their implications stand as a central point of inquiry. The discussion will delve into the forensic and historical analysis of these wounds, seeking to understand their origins and the story they tell. This exploration is not just an academic exercise but a journey into the heart of a narrative that has shaped centuries of thought and belief, offering insights into the physical realities that underpin a pivotal moment in history.

The Spear Wound

The front image of the cloth bears a stark and poignant mark: an elliptical wound approximately 2 inches wide, a detail that aligns with the dimensions of a Roman spear. This wound, referenced in the Gospel of John (19:34), is not just a testament to the brutality of the act but also serves as a crucial piece of forensic evidence that supports the cloth's authenticity. The shape and size of the wound are consistent with the historical understanding of Roman weaponry, providing a tangible link to the methods of execution used during the period. More significantly, the area surrounding this wound reveals traces of both blood and a watery fluid, suggestive of a post-mortem flow. This detail is crucial, as it indicates that the wound was inflicted after death, consistent with the biblical account of the piercing of Jesus' side to confirm His death. The presence of both blood and a separate watery fluid mirrors the scriptural description of "blood and water" flowing from the wound, a phenomenon that occurs when blood settles and separates into its constituent parts after the heart has stopped beating. The accuracy of this detail on the cloth—both in terms of the wound's dimensions and the nature of the fluids emanating from it—challenges the notion of a medieval forgery. Reproducing such precise physiological reactions and Roman military specifics would have been nearly impossible without a deep understanding of post-mortem blood separation and the exact dimensions of Roman spears, knowledge not typical of the medieval period. This wound, with its forensic and historical fidelity, invites a deeper examination of the cloth's origins and the events it purports to document. It stands as a focal point for discussions at the conference, where experts from various fields will delve into the implications of this and other features of the cloth. The aim is to unravel the layers of history, science, and theology intertwined within the fabric, offering insights into the enduring mystery of the cloth and the narrative it carries.

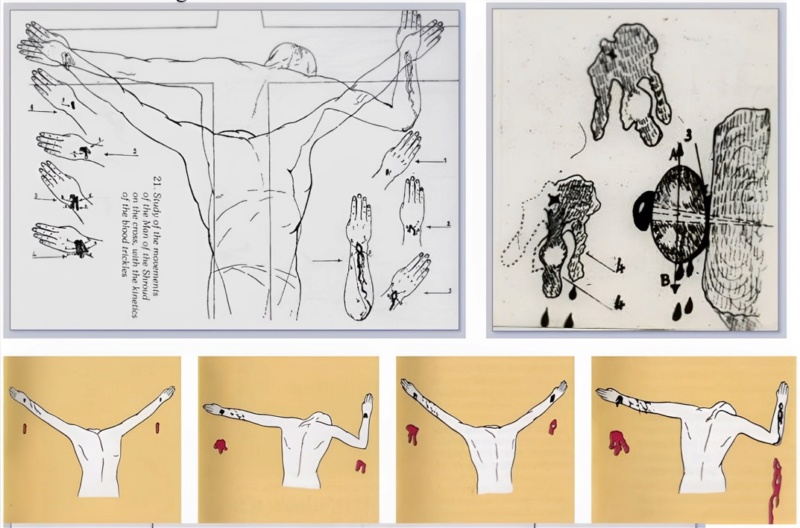

The Blood Evidence

The analysis of the bloodstains on the cloth reveals a level of detail that significantly corroborates the crucifixion narrative. The blood flow patterns on the arms, displaying two distinct angles, reflect the physiological response of a crucified individual alternating between positions to breathe. This shifting, a desperate measure to alleviate the suffocation inherent in crucifixion, is mirrored in the blood flow directions observed on the cloth, lending credence to its authenticity as the burial shroud of a crucifixion victim. Further bolstering the case for authenticity, the substance identified as blood on the cloth has undergone a battery of tests, affirming its biological origin. These tests have conclusively proven that the stains are composed of real human blood, characterized by the presence of both "X" and "Y" chromosomes, indicative of a male origin. The determination of the blood type as AB adds another layer of specificity to the biological evidence. The blood's high bilirubin content is particularly telling. Bilirubin levels rise in response to the breakdown of red blood cells, a condition consistent with severe physical trauma, such as a beating. This biochemical marker aligns with the historical accounts of the physical sufferings endured, providing a poignant testament to the brutality of the events leading up to the crucifixion. Contrary to expectations for ancient bloodstains, which typically darken to a black or deep brown over time, the blood on the cloth retains a reddish hue. This unusual coloration has been the subject of much speculation and scientific inquiry, with multiple theories proposed to explain the phenomenon. Among these, the high bilirubin content itself is a plausible factor, as it can impact the degradation and coloration of blood over time. The confluence of forensic, historical, and scriptural evidence as represented by the bloodstains on the cloth offers a compelling argument for its authenticity. The detailed examination of these stains provides not only a window into the physical realities of crucifixion but also a testament to the individual's identity and the ordeal endured.

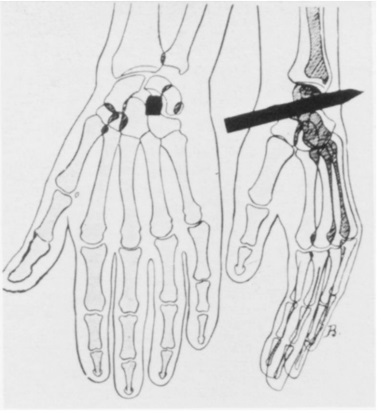

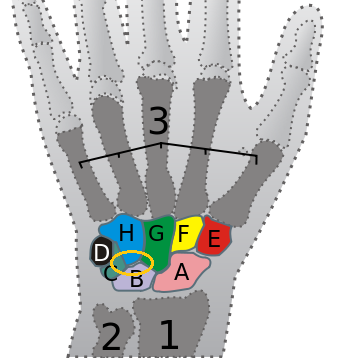

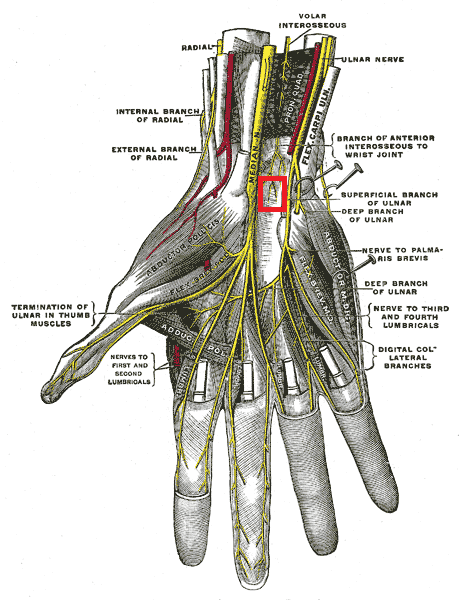

Nail Marks on the Shroud

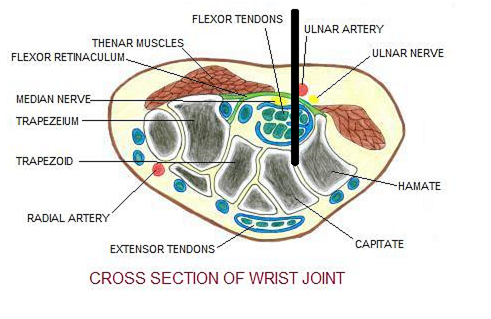

The depiction of crucifixion in medieval art often presents a stylized interpretation, with nails piercing the palms of the hands. This imagery, while iconic, contradicts the practical and anatomical realities of crucifixion as understood through archaeological findings and historical research. The palms, lacking the structural support of bone above the area of penetration, would not have been able to sustain the weight of a human body during crucifixion. Archaeological evidence has clarified this aspect, showing that nails were more likely driven through the wrists, where the bones could provide the necessary support. The cloth, in stark contrast to medieval artistic conventions, displays a remarkable adherence to this anatomical and archaeological understanding. The marks suggestive of nail wounds are located not in the palms but in the wrists, aligning with the more accurate portrayal of Roman crucifixion practices. This detail is not only consistent with the physical realities of such an execution but also with the findings from archaeological excavations of crucifixion victims. The precise location of the nail marks on the cloth challenges the notion of a medieval origin, as it predates widespread archaeological insights by centuries. The accuracy of these marks suggests a level of knowledge about crucifixion practices that was not common during the Middle Ages, further supporting the cloth's authenticity as a genuine burial shroud of a crucifixion victim. This congruence between the nail mark locations on the cloth and the archaeological understanding of crucifixion practices adds a significant layer of historical credibility to the artifact. It invites a reevaluation of the cloth's origins and the events it is believed to depict, bridging the gap between historical artifacts and scriptural accounts.

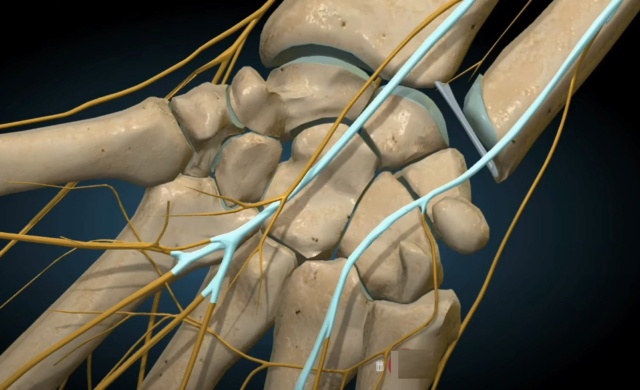

The Unique Depiction of Thumbs on the Shroud

The cloth presents an anatomical detail that significantly diverges from the iconography typical of medieval art: the thumbs are depicted as folded under, a posture not seen in the conventional representations of the crucifixion from the Middle Ages. This specific detail provides a compelling insight into the physiological reactions to the crucifixion process, particularly about the placement of the nails. Nailing through the wrists, as opposed to the palms, would likely impact the median nerves, leading to an involuntary reflexive contraction of the thumbs. This physiological response is accurately reflected on the cloth, suggesting a level of anatomical understanding that surpasses the artistic conventions of the time. The absence of the thumbs in the image aligns with what would be expected from nail placement through the wrist, further corroborating the cloth's depiction of crucifixion with historical and anatomical accuracy. This detail challenges the notion that the image could be a medieval creation, as it incorporates a nuanced understanding of human anatomy that was not widely recognized until much later. The precise portrayal of the thumbs adds to the growing body of evidence supporting the cloth's authenticity, suggesting that its creation was the result of direct contact with a crucified body rather than an artistic endeavor. The discussion of this unique anatomical feature at the conference will delve into the intersection of art, history, and medicine, exploring how the cloth's depiction of crucifixion stands apart from contemporary artistic representations. This exploration will contribute to a deeper understanding of the cloth's origins and the events it is believed to represent, highlighting its significance as a historical and religious artifact.

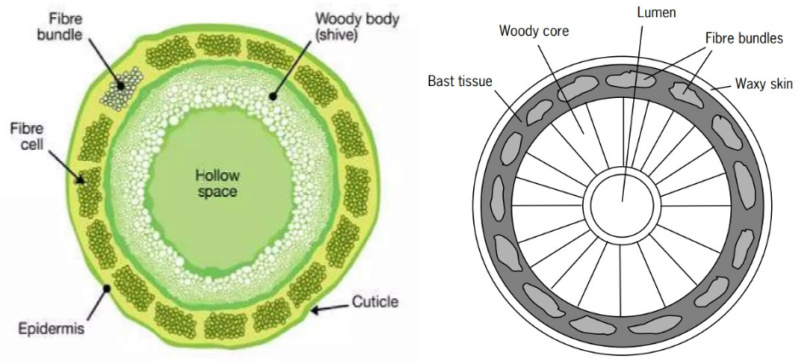

The Masada Stitch

A distinctive feature of the cloth that has intrigued scholars is the three-inch wide side strip, attached with a sewing technique that bears a striking resemblance to a stitch found exclusively at Masada, a site destroyed in 73-74 AD. This unique stitch, nearly identical to the one employed in the construction of textiles unearthed at Masada, provides compelling evidence pointing towards the cloth's creation in the first century. The presence of this stitch on the cloth is more than a mere curiosity; it serves as a tangible link to a specific time and place in history, offering a clue to the cloth's origins that align with the era of the crucifixion. The rarity of this stitching technique, coupled with its geographical and temporal association with Masada, strongly suggests that the cloth, and by extension the side strip, originates from a similar period. The purpose of the three-inch side strip remains a subject of speculation, yet the prevailing theory suggests it was integral to the cloth's original construction. This could indicate a practical aspect of textile making at the time, perhaps related to the dimensions or the intended use of the cloth. The meticulous attachment of this strip, utilizing a stitch characteristic of the period and region, further underscores the cloth's historical authenticity and its potential as a first-century artifact. The discussion of the side strip and its unique stitch at the conference will delve into the broader implications of textile evidence in understanding the cloth's origins. By examining the sewing techniques, materials, and patterns used in the cloth's construction, scholars aim to shed light on the cultural and historical context in which it was made. This exploration not only enriches our understanding of the cloth itself but also offers insights into the textile practices of the era, contributing to a more nuanced appreciation of the artifact's significance in the tapestry of history.

The Limestone Evidence on the Shroud

Among the myriad of clues the cloth offers, one of the most compelling is the presence of small chips of travertine aragonite limestone found in the dirt near the image's feet. This particular type of limestone, known as "Jerusalem limestone," is predominantly found in the Jerusalem area, offering a geographical marker that ties the cloth directly to this historic locale. The spectral analysis of these limestone particles reveals a near-identical match with samples from the area surrounding the Damascus Gate, the gateway nearest to Golgotha, the site traditionally recognized as the location of the crucifixion. This remarkable correspondence in the spectral signature between the limestone on the cloth and that of Jerusalem's environs strongly suggests that the individual whose death is memorialized on the cloth had indeed traversed the streets of Jerusalem before the crucifixion. The specificity of this limestone, unique to Jerusalem, serves as a geological fingerprint, providing substantive evidence that anchors the cloth in a specific time and place. The implications of this finding extend beyond mere geographical significance; they offer a tangible connection to the historical setting of the crucifixion narrative. This limestone evidence supports the authenticity of the cloth as a burial shroud of someone who was in Jerusalem in the first century, aligning with the historical period of the events described in the New Testament. As scholars gather to discuss the multifaceted evidence presented by the cloth, the limestone findings will be a focal point, offering insights into the environmental and geological context of the era. This discussion will explore the integration of geological science with historical and scriptural analysis, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the cloth's origins and the events it is believed to depict. Through this interdisciplinary exploration, the limestone evidence on the cloth stands as a testament to the historical and geographical authenticity of the narrative it bears. There is one item that should be on a burial cloth such as this that is not present. That one item is the product of the body's decay. There are no body decay products on the Shroud of Turin, even though the pristine nature of the blood marks indicates that this Shroud was not lifted off of the body from which the blood had come.

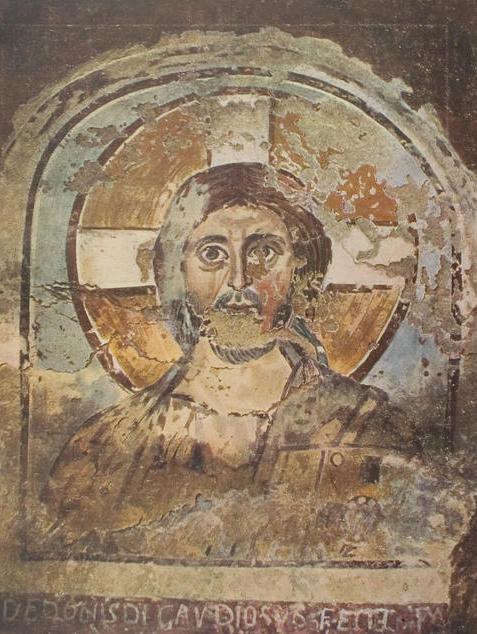

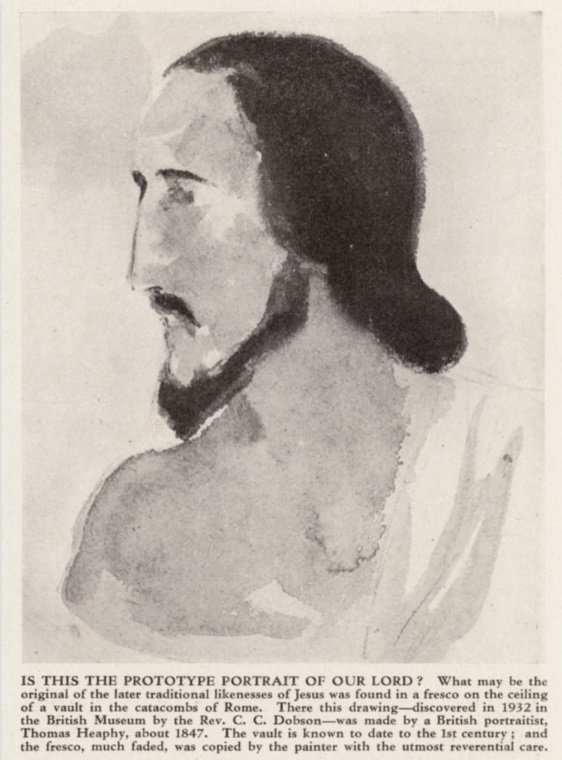

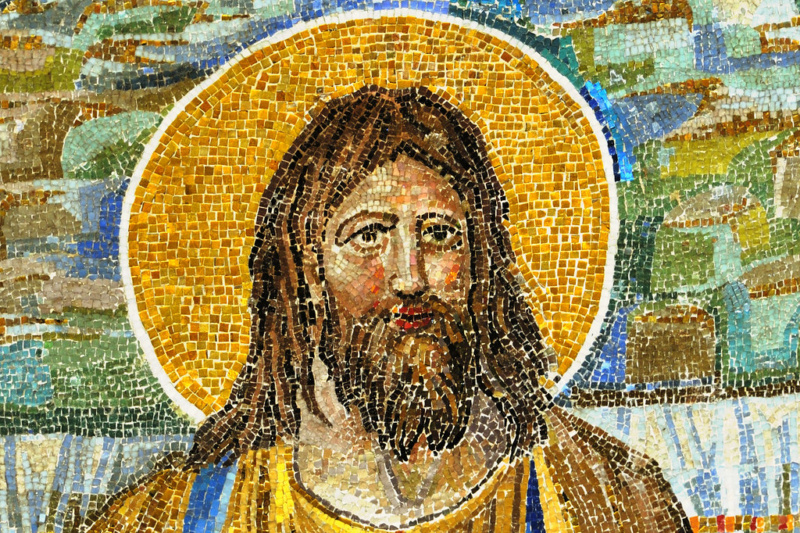

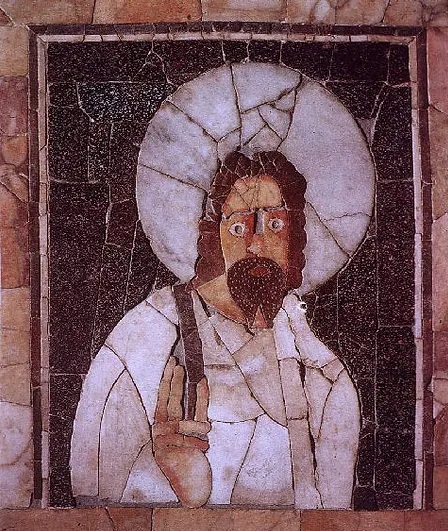

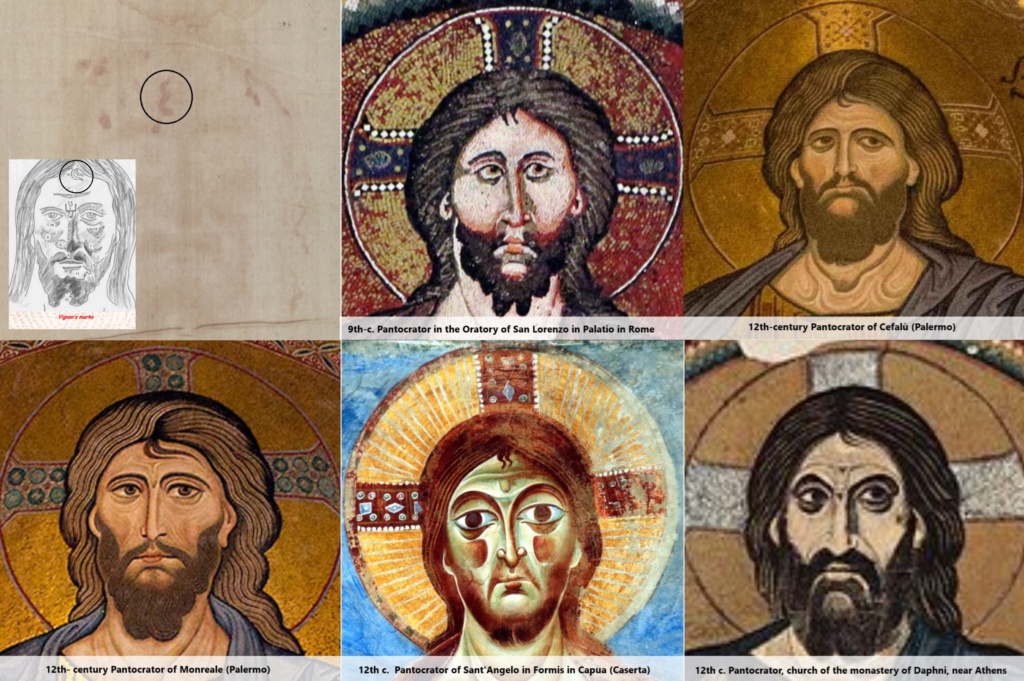

Pre-1355 History of the Shroud: Evolution of Christ Iconography

Chronology of the Shroud

On August 9th, 48 BC, a significant event in the Roman Civil War unfolded at Pharsalus in central Greece, where Julius Caesar and his legions triumphed over the larger forces led by Pompey the Great, aligned with the Roman Senate. Following his defeat, Pompey fled with remnants of his army to Egypt, only to be assassinated upon his arrival. Caesar, chasing Pompey, arrived in Alexandria to find himself amid Egypt's civil conflict, becoming a target for local factions. Facing a large Egyptian military force aiming to eliminate him, Caesar's situation seemed dire. At this critical juncture, Antipater the Idumaen, a lesser-known leader from near Judea, intervened significantly. Josephus documented Antipater's arrival with 3,000 armed Jewish men, alongside support from Arabs and Syrians, bolstering Caesar's position. This support not only facilitated Caesar's survival but also contributed to the eventual shift from the Roman Republic to Caesar's autocratic rule. Caesar, in gratitude, appointed Antipater as procurator of Judea, laying the foundations for the Herodian Dynasty, which would have profound implications for early Christian history. Antipater's son, Herod the Great, and his descendants, including Herod Agrippa and Herod Antipas, played pivotal roles in the New Testament narratives, from the massacre of Bethlehem's infants to the crucifixion of Jesus and the persecution of early Christians. Despite the Herodians' adversarial actions towards Christianity, Antipater's aid to Caesar indirectly fostered the religion's growth. Caesar's subsequent decrees granted religious freedoms to Jews throughout the Roman Empire, inadvertently creating conducive environments for the spread of Christianity. These Jewish communities and their synagogues, along with their Gentile neighbors, became fertile ground for the missionary efforts of early Christian figures like Peter and Paul, significantly aiding in the propagation of the Christian faith.

In 34 AD, following the stoning of Stephen, the first Christian martyr, in Jerusalem, a wave of persecution swept through the early Christian community. This led to many followers of Jesus seeking refuge beyond the city, spreading their message to Jewish communities in Phoenicia, Cyprus, and particularly in Antioch. It's believed that Barnabas was dispatched to Antioch, possibly on the instruction of Peter. At that time, Antioch was a major urban center of the Roman Empire, ranked only behind Rome and Alexandria in Egypt in terms of importance. Around 40 AD, under the guidance of Barnabas and later Paul, Christian missionaries in Antioch began to increasingly direct their evangelistic efforts towards non-Jewish populations. This marked the beginning of Antioch's pivotal role as a hub for Christian missionary activity. Following the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD, Antioch emerged as the preeminent center of Christianity, boasting the largest Christian community in the world at that time. It was in Antioch that the term "Christian" was first coined, earning the city the title "Cradle of Christianity." Additionally, St. Luke, a native of Antioch, composed both the Gospel according to Luke and the Acts of the Apostles within this vibrant city.

Peter's missionary endeavors are less clearly defined than Paul's well-documented journeys. While we don't have precise dates and routes for Peter's travels, insights can be gleaned from the First Epistle of Peter. This letter, possibly penned by Peter from Rome around 60-63 AD or by a follower between 70-90 AD, is a theological gem of the New Testament, offering deep insights into Christology, the nature of the Church, and Christian conduct. The epistle's greeting hints at Peter's missionary reach, addressing believers scattered across Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia, and Bithynia. This suggests Peter's involvement in these regions, whether through direct visits or his influence. Further historical texts, like the fifth or sixth-century Doctrine of the Apostles, record Peter's foundational role in establishing the church in areas including Antioch, Syria, Cilicia, and Galatia, leading up to his time in Rome. Peter's timeline, traditionally accepted, includes:

Around 35 AD, Peter is believed to have played a key role in founding the church in Antioch, later returning to Jerusalem by around 40 AD, and being present there in 42 AD. In 42 AD, Peter faced threats from Herod Agrippa, leading to his miraculous escape from imprisonment. Despite Acts of the Apostles mentioning Peter's brief stay in Caesarea, many scholars speculate his journey led him to Rome, a significant center for the Jewish diaspora and fertile ground for spreading the Gospel. Peter is noted to have returned to Jerusalem around 44 AD for the Jerusalem Council, which took place circa 49-50 AD. This council was pivotal in deciding that Gentile converts need not fully adhere to Jewish customs, including circumcision. Following the council, tradition places Peter back in Antioch until around 54-55 AD, after which he is said to have embarked on a second journey to Rome. Peter's final years were spent evangelizing in Rome and Italy, culminating in his martyrdom under Emperor Nero, approximately between 64-68 AD. This timeline, while not exhaustive, sketches a broad outline of Peter's contributions to the early Christian mission, reflecting his pivotal role alongside Paul in the spread of Christianity.

Between 68 and 70 AD, amidst the turmoil and onset of hostilities in Jerusalem involving Jewish zealots and Roman authorities, key Christian artifacts, including an "image of our Holy Lord and Savior," were transported out of the city for safety. This period followed the martyrdom of James in 62 AD and was marked by escalating tensions that eventually led to open conflict in 66 AD. Recognizing the imminent danger, members of the Jerusalem Church sought refuge, many heading towards Antioch and other safe havens in Syria. This exodus, including the safeguarding of sacred objects, is documented in a sermon attributed to Saint Athanasius, the 4th-century Bishop of Alexandria. Delivered during the Second Council of Nicaea in 787, Athanasius' sermon recounts the careful removal of a significant Christian relic, described as a full-length "image of our Lord and Savior," from Jerusalem to Syria around 68 AD, as part of the broader effort to protect the Christian community and its heritage from the perils of the Jewish-Roman conflict.

“But two years before Titus and Vespasian sacked the city, the faithful and disciples of Christ were warned by the Holy Spirit to depart from the city and go to the kingdom of King Agrippa II, because at that time Agrippa II was a Roman ally. Leaving the city, they went to his regions and carried everything relating to our faith. At that time even the icon with certain other ecclesiastical objects were moved and they today still remain in Syria. I possess this information as handed down to me from my migrating parents and by hereditary right. It is plain and certain why the icon of our Holy Lord and Savior came from Judaea to Syria."

Encyclopedia, Vol. V, Robert Appleton Company (New York 1907-1914)

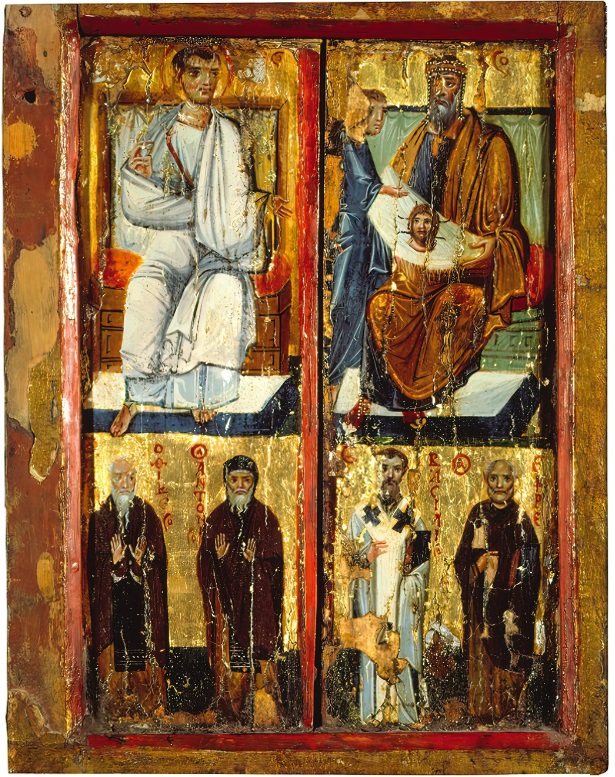

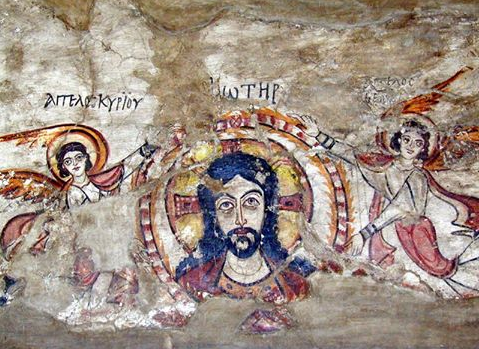

Apostle Thaddeus and King Abgar Icon. St. Catherine monastery (Sinai) Byzantine. Empire, 10th C.

The Image of Edessa

The Image of Edessa, also known as the Mandylion, is intertwined with the tale of how Christianity came to Edessa. The legend of the Mandylion claims that Taddai brought the Shroud soon after 33AD to Edessa. This story is told in the document known as "The Teaching of Addai," a text that dates back to the late 4th or early 5th century. According to tradition, King Abgar V of Edessa, suffering from an illness, heard of Jesus Christ's miraculous healings and sent a correspondence to him, requesting both healing and that Jesus seek refuge in his city. In the account recorded in "The Teaching of Addai," rather than Jesus Himself visiting Edessa, He sends one of His disciples, Thaddeus (also referred to as Addai), in His stead after the Ascension. Thaddeus arrives in Edessa, heals King Abgar, and facilitates the conversion of the king and his subjects to Christianity.

Last edited by Otangelo on Tue Mar 12, 2024 9:32 am; edited 33 times in total