Working Gears in Plant-Hopping Insect - by evolution, or design?

https://reasonandscience.catsboard.com/t3012-working-gears-in-plant-hopping-insect-by-evolution-or-design

Issus: The Inventor of Gears?

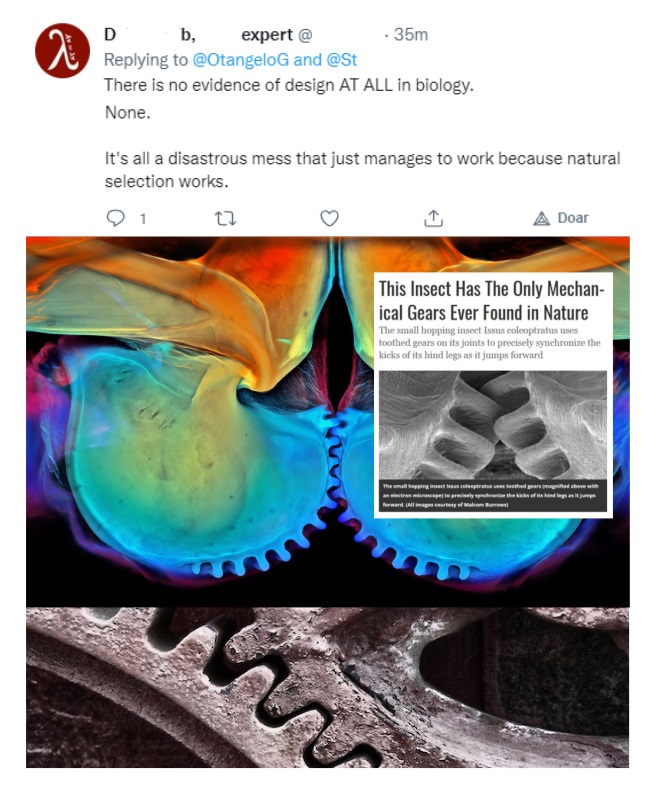

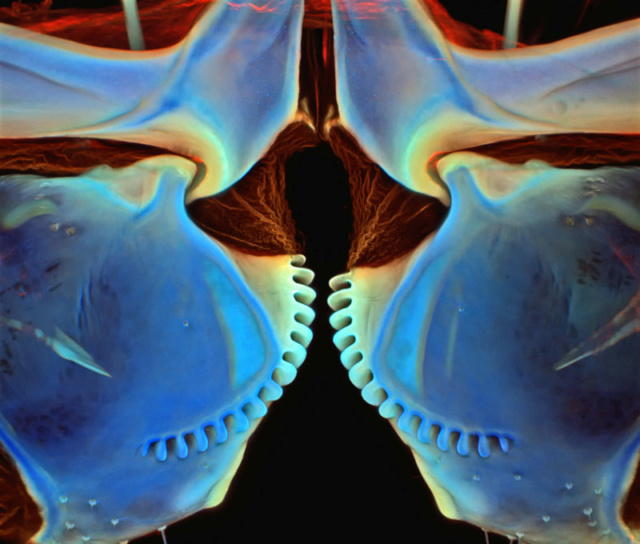

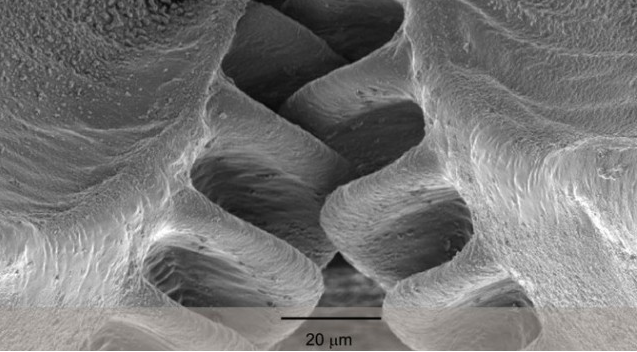

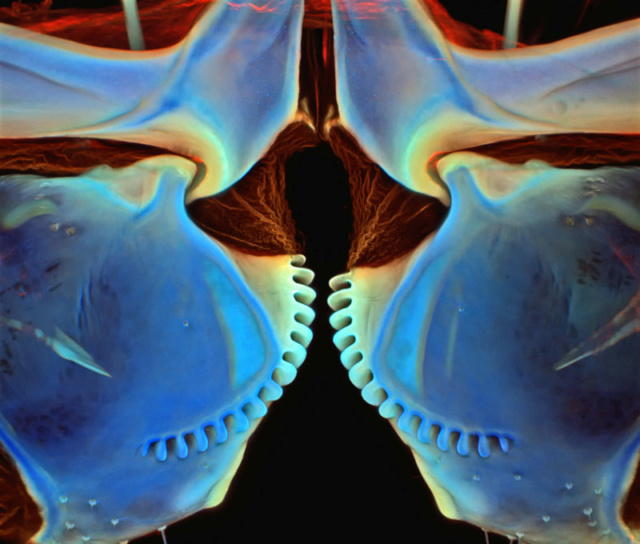

For flightless insects, the ability to jump high, fast, and with great precision is essential for their survival. To avoid being eaten, a flightless insect must be able to jump from the time it is born. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that small insects are among the best jumpers on this planet. But light insects with small bodies taking large leaps pose a big engineering problem. To make matters more difficult, insects have pairs of legs, so the leaping action must be perfectly coordinated, the legs pushing forward more or less simultaneously. There’s not much room for trial and error. How do these creatures manage it? What follows is one particularly extraordinary strategy. In 2013, two biologists were studying a tiny insect, a nymphalid planthopper in the genus Issus, a creature found throughout Europe and North Africa. What they discovered sounds like something off the pages of Popular Mechanics’ What’s New section. This tiny insect jumps using interlocking gears on its hindleg trochanters, which connect the legs to the insect equivalent of a hip. Using this miniaturized technology, these tiny insects, barely larger than a flea, move their legs in near-perfect coordination. Because both legs swing laterally, if one were extended a split second before the other, the insect would end up in a spin and become easy food. But the gears are so finely engineered that the creatures can jump fast, far, and straight. Their cuticular mechanical gears intermesh and rotate with great precision, coordinating the legs. Each gear rotates within thirty-millionths of a second of the other at more than 33,000 RPM (revolutions per minute). The highest-revving production sports car engines only reach around 10,000 RPM.The gears also synchronously cock the legs before triggering forward jumps, using asymmetric (better than symmetric) teeth. Close registration between the gears ensures that both hindlegs move at the same angular velocities to propel the insect’s body without yaw rotation (twisting about a vertical axis).17 Infant Issus can jump one hundred times their length and at speeds as high as 3.9 meters per second. But the risk of breaking such a tiny high-speed device is high. To offset this risk, the gears are constantly replaced by new ones in the juvenile insect. The juvenile Issus repeatedly develop new gears as they grow so that if the gear is damaged, they just have to survive for a short period until a new, undamaged pair has arrived. For the heavier adult, the gears are changed out for a more robust device suitable to the adult’s larger size—a high-performance friction-based mechanism. This too suggests foresight. At present, it appears that the juvenile nymphalid planthopper Issus is the only creature that uses interlocking toothed mechanical gears to perfectly synchronize its limbs for long-distance jumps.

Until this discovery, gears had never before been found to allow ballistic jumping movements. If evolution somehow created this engineering marvel, it seems to have done it as a one-off. In discussing the most likely origin for the Issus gears, Scientists describing the insect considered the two scientifically possible options, but then selected the wrong one—the one that lacks the demonstrated capacity for engineering such marvels. “These gears are not designed; they are evolved—representing high speed and precision machinery evolved for synchronization in the animal world.” As is usual with such claims, it is not followed by an account of how this gear-based jumping system might have evolved one small functional step at a time, a pathway essential if some form of blind Darwinian evolution produced it. But no matter; we apparently are expected to embrace that scenario as settled dogma anyway. Instead, let’s reason through the claim. Suppose, for the sake of argument, that Issus had existed and was able to live long enough to escape extinction without the juvenile gear or an adult friction mechanism. Why would it risk evolving two new, distinct jumping mechanisms? Because evolution works in small steps, it must make an imperfect gear or friction system first. Suppose it switched things and gave the gears to the adult and the friction mechanism to the juvenile? The poor mutant Issus would test out this new function, only to find out it failed to work. And even if evolution selected the right age for each function, infant Issus would discover that the new gear material was too soft, or the number and spacing of the teeth were off, or the push was too much to the right or to the left, causing the creature to spin out of control and crash. There are numerous things that could go wrong. An imperfect gear system, in this case, is no good at all. And which came first? Gears for the juvenile, or the friction system better suited for the adult Issus? It would need both, since the creature would always need to be able to jump to survive, as a juvenile and as an adult. Plan and deliver an exquisitely engineered pair of jumping systems from the start—one for the juvenile and one for the adult—or adios, little insect. Unquestionably, the Issus gears are an example of high technology.

One final piece of evidence to drive home the point: The risk for such high-tech and demanding 33,000+ RPM gears is great: If any tooth is damaged, the effectiveness of the designed gear is lost. To minimize the risk, the eighty-millionths-of-a-meter-wide teeth are equipped with filleted curves at the base. Humans eventually invented similar techniques to get more torque and reduce wear over time, but nature got there first. Functional gears of any kind are ingeniously crafted devices. They come in many forms and are used for many purposes. They are a keystone of modern technology, present in many types of machinery, cars, and bicycles. As far as human history goes, it seems that no one knows for sure who invented mechanical gears, but we do know the Greeks used them in the world’s earliest known analogical computer, the Antikythera mechanism, which is now thought to have been used to chart the movements of the sun, the moon, and the planets visible to the naked eye. When in 1900 Greek sponge divers found this ancient mechanism— the most advanced technological mechanism as yet discovered from antiquity—and they saw the gears, they immediately recognized it as the product of an intelligent mind. If no other type of cause has the demonstrated capacity to generate such marvels, why should we respond differently when we find exquisitely crafted gears attached to the legs of a jumping insect, particularly when the imaginative stories of the blind evolution of such natural wonders go begging for credible detail?

Text from: Eberlin, foresight

Mechanical gears in jumping insects

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q8fyUOxD2EA

https://reasonandscience.catsboard.com/t3012-working-gears-in-plant-hopping-insect-by-evolution-or-design

Issus: The Inventor of Gears?

For flightless insects, the ability to jump high, fast, and with great precision is essential for their survival. To avoid being eaten, a flightless insect must be able to jump from the time it is born. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that small insects are among the best jumpers on this planet. But light insects with small bodies taking large leaps pose a big engineering problem. To make matters more difficult, insects have pairs of legs, so the leaping action must be perfectly coordinated, the legs pushing forward more or less simultaneously. There’s not much room for trial and error. How do these creatures manage it? What follows is one particularly extraordinary strategy. In 2013, two biologists were studying a tiny insect, a nymphalid planthopper in the genus Issus, a creature found throughout Europe and North Africa. What they discovered sounds like something off the pages of Popular Mechanics’ What’s New section. This tiny insect jumps using interlocking gears on its hindleg trochanters, which connect the legs to the insect equivalent of a hip. Using this miniaturized technology, these tiny insects, barely larger than a flea, move their legs in near-perfect coordination. Because both legs swing laterally, if one were extended a split second before the other, the insect would end up in a spin and become easy food. But the gears are so finely engineered that the creatures can jump fast, far, and straight. Their cuticular mechanical gears intermesh and rotate with great precision, coordinating the legs. Each gear rotates within thirty-millionths of a second of the other at more than 33,000 RPM (revolutions per minute). The highest-revving production sports car engines only reach around 10,000 RPM.The gears also synchronously cock the legs before triggering forward jumps, using asymmetric (better than symmetric) teeth. Close registration between the gears ensures that both hindlegs move at the same angular velocities to propel the insect’s body without yaw rotation (twisting about a vertical axis).17 Infant Issus can jump one hundred times their length and at speeds as high as 3.9 meters per second. But the risk of breaking such a tiny high-speed device is high. To offset this risk, the gears are constantly replaced by new ones in the juvenile insect. The juvenile Issus repeatedly develop new gears as they grow so that if the gear is damaged, they just have to survive for a short period until a new, undamaged pair has arrived. For the heavier adult, the gears are changed out for a more robust device suitable to the adult’s larger size—a high-performance friction-based mechanism. This too suggests foresight. At present, it appears that the juvenile nymphalid planthopper Issus is the only creature that uses interlocking toothed mechanical gears to perfectly synchronize its limbs for long-distance jumps.

Until this discovery, gears had never before been found to allow ballistic jumping movements. If evolution somehow created this engineering marvel, it seems to have done it as a one-off. In discussing the most likely origin for the Issus gears, Scientists describing the insect considered the two scientifically possible options, but then selected the wrong one—the one that lacks the demonstrated capacity for engineering such marvels. “These gears are not designed; they are evolved—representing high speed and precision machinery evolved for synchronization in the animal world.” As is usual with such claims, it is not followed by an account of how this gear-based jumping system might have evolved one small functional step at a time, a pathway essential if some form of blind Darwinian evolution produced it. But no matter; we apparently are expected to embrace that scenario as settled dogma anyway. Instead, let’s reason through the claim. Suppose, for the sake of argument, that Issus had existed and was able to live long enough to escape extinction without the juvenile gear or an adult friction mechanism. Why would it risk evolving two new, distinct jumping mechanisms? Because evolution works in small steps, it must make an imperfect gear or friction system first. Suppose it switched things and gave the gears to the adult and the friction mechanism to the juvenile? The poor mutant Issus would test out this new function, only to find out it failed to work. And even if evolution selected the right age for each function, infant Issus would discover that the new gear material was too soft, or the number and spacing of the teeth were off, or the push was too much to the right or to the left, causing the creature to spin out of control and crash. There are numerous things that could go wrong. An imperfect gear system, in this case, is no good at all. And which came first? Gears for the juvenile, or the friction system better suited for the adult Issus? It would need both, since the creature would always need to be able to jump to survive, as a juvenile and as an adult. Plan and deliver an exquisitely engineered pair of jumping systems from the start—one for the juvenile and one for the adult—or adios, little insect. Unquestionably, the Issus gears are an example of high technology.

One final piece of evidence to drive home the point: The risk for such high-tech and demanding 33,000+ RPM gears is great: If any tooth is damaged, the effectiveness of the designed gear is lost. To minimize the risk, the eighty-millionths-of-a-meter-wide teeth are equipped with filleted curves at the base. Humans eventually invented similar techniques to get more torque and reduce wear over time, but nature got there first. Functional gears of any kind are ingeniously crafted devices. They come in many forms and are used for many purposes. They are a keystone of modern technology, present in many types of machinery, cars, and bicycles. As far as human history goes, it seems that no one knows for sure who invented mechanical gears, but we do know the Greeks used them in the world’s earliest known analogical computer, the Antikythera mechanism, which is now thought to have been used to chart the movements of the sun, the moon, and the planets visible to the naked eye. When in 1900 Greek sponge divers found this ancient mechanism— the most advanced technological mechanism as yet discovered from antiquity—and they saw the gears, they immediately recognized it as the product of an intelligent mind. If no other type of cause has the demonstrated capacity to generate such marvels, why should we respond differently when we find exquisitely crafted gears attached to the legs of a jumping insect, particularly when the imaginative stories of the blind evolution of such natural wonders go begging for credible detail?

Text from: Eberlin, foresight

Mechanical gears in jumping insects

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q8fyUOxD2EA