Hyolith, An Ancient 'Ice Cream Cone' 1

http://reasonandscience.heavenforum.org/t2664-hyolith-an-ancient-ice-cream-cone

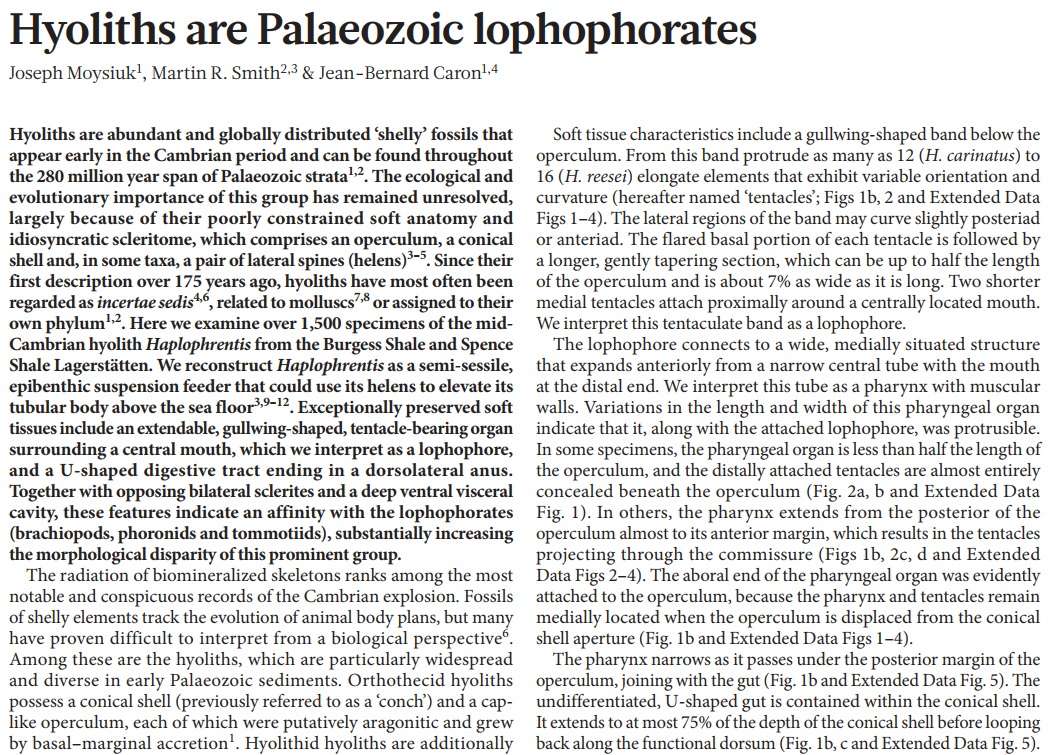

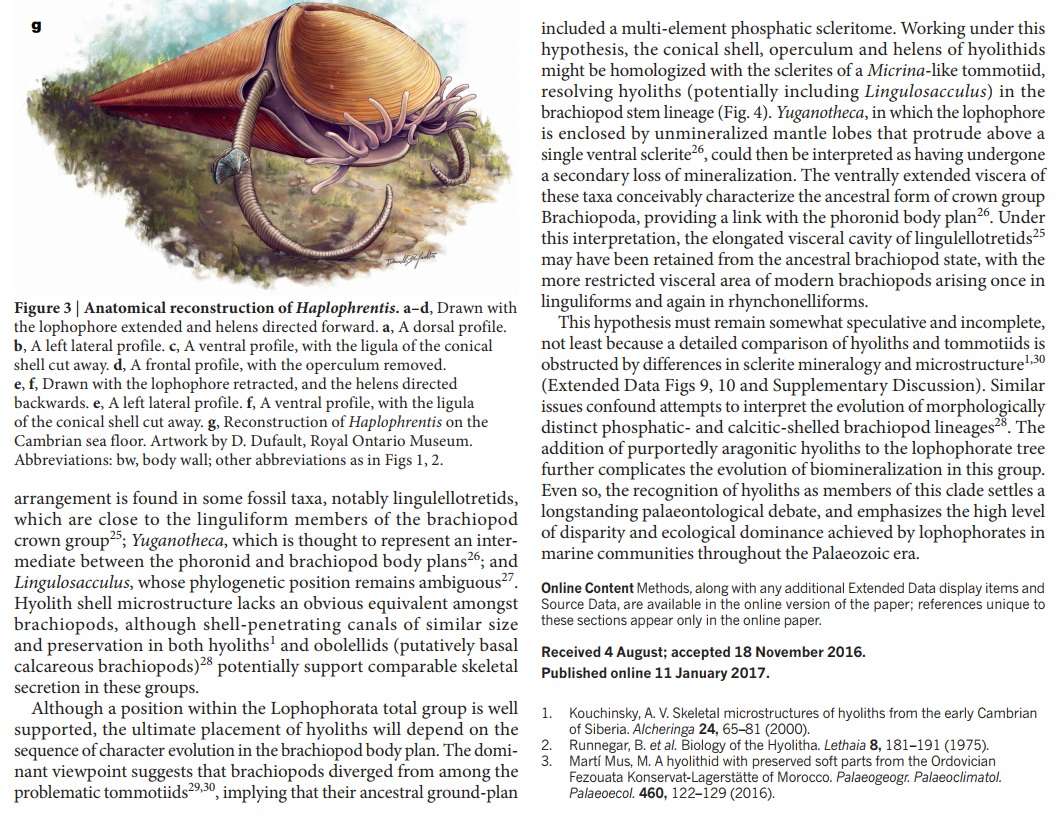

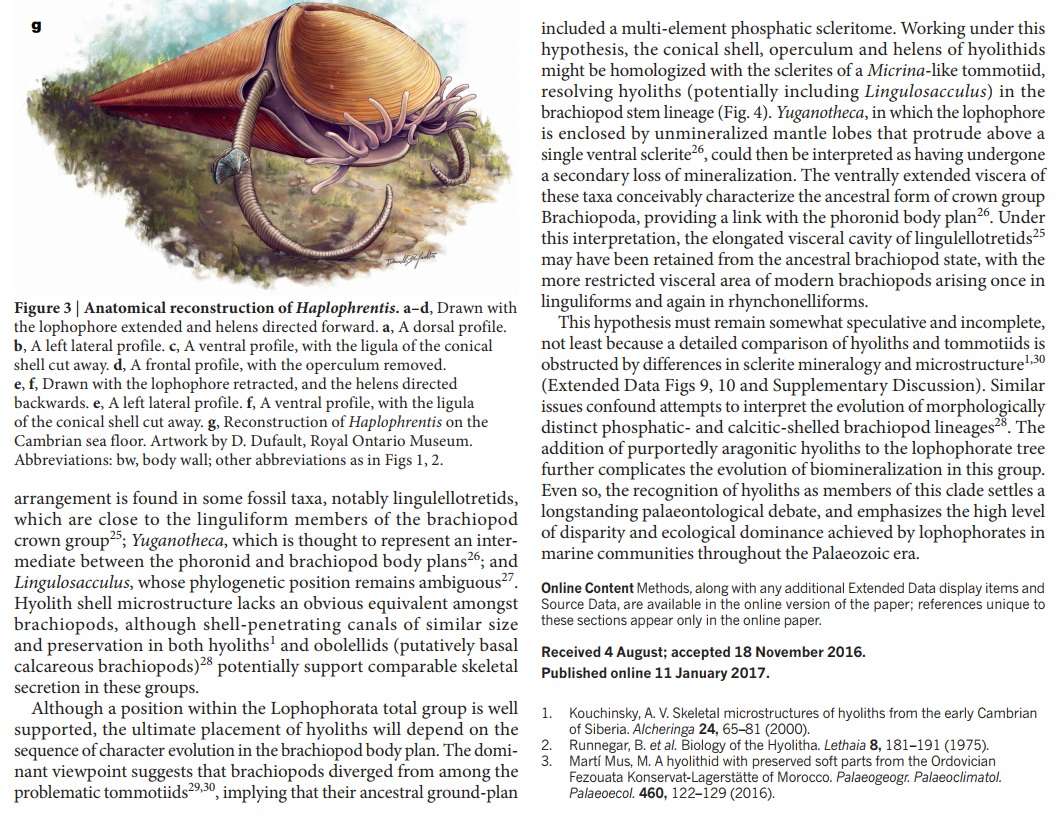

The hyolith Haplophrentis extends the tentacles of its feeding organ (lophophore) from between its shells. The paired spines, or "helens," are propping the animal up off the ocean floor. 2

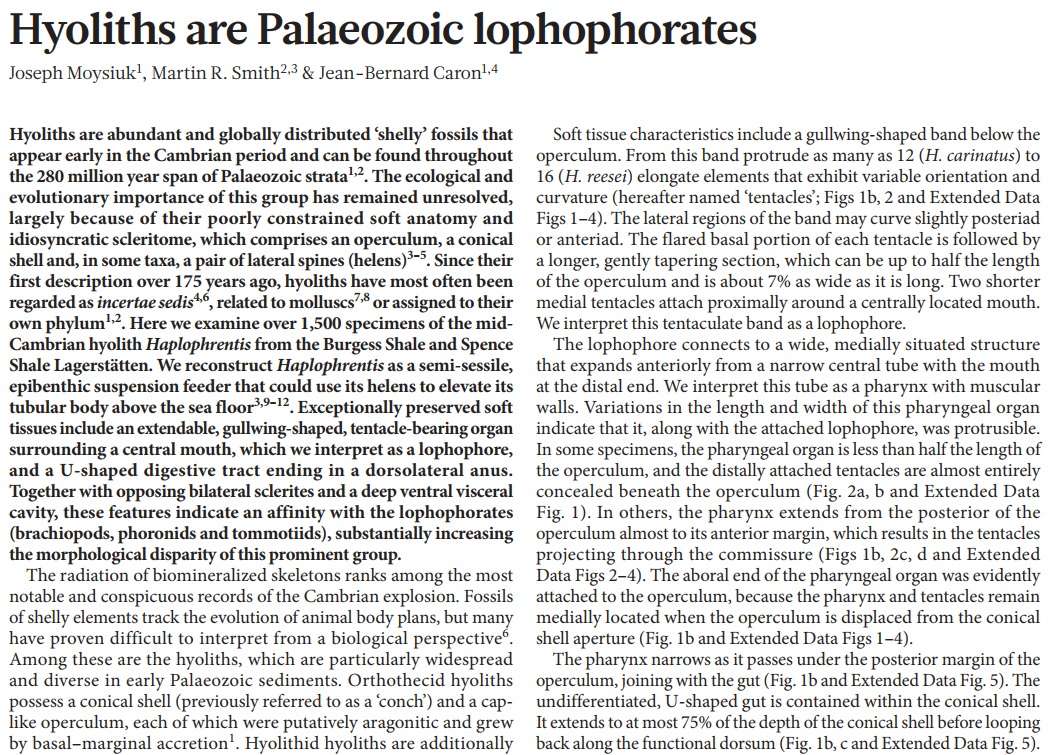

Hyoliths, an enigmatic group of Paleozoic invertebrates have long puzzled paleontologists. A new analysis of hundreds of specimens shows that they are close relatives of brachiopods or lamp shells.

If you were to describe the shells of a hyolith to someone, they may think you're describing the home of a minor character from SpongeBob SquarePants: imagine a kind of squished ice cream cone with a trapdoor. Also, poking out of the gap in the door are two curled stilts.

As absurd as it sounds, creatures fitting that description were common in Cambrian oceans more than 500 million years ago and, although they became less common after the Cambrian, persisted until the Permo-Triassic Extinction 252 million years ago.

Hyoliths are unlike any living organisms and have puzzled paleontologists since their discovery nearly two centuries ago. Many paleontologists grouped them with mollusks, or considered them to be in their own group, with uncertain relationships to other animals.

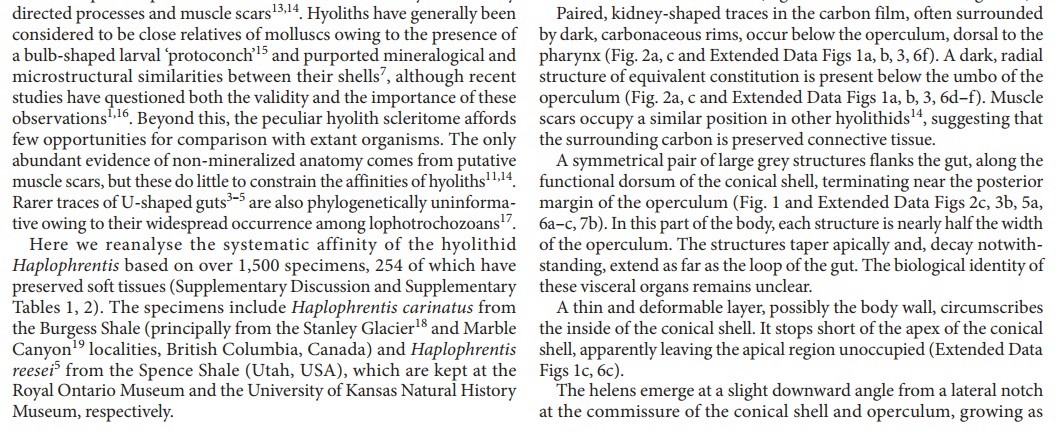

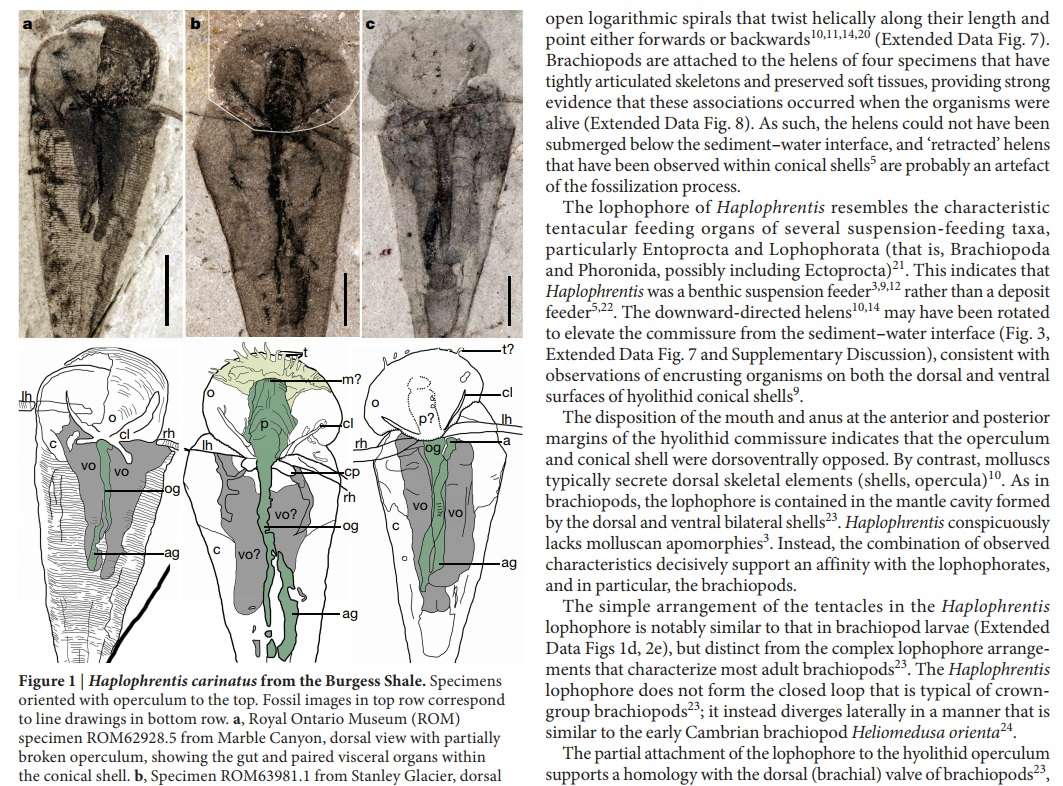

In early 2017 paleontologists Joseph Moysiuk, Martin Smith, and Jean-Bernard Caron published a paper analyzing over 1500 specimens of the Cambrian hyolith named Haplophrentis, known from the Burgess Shale in British Columbia, Canada and the Spence Shale in Utah, USA. Both the Burgess Shale and Spence Shale are what are known as lagerstätten, rock formations that preserve fossils in exceptional detail including soft tissues.

More than 250 examples of Haplophrentis preserve soft tissues which allowed Moysiuk and colleagues to reconstruct the internal organs of the living animals and determine where hyoliths are located on the tree of life.

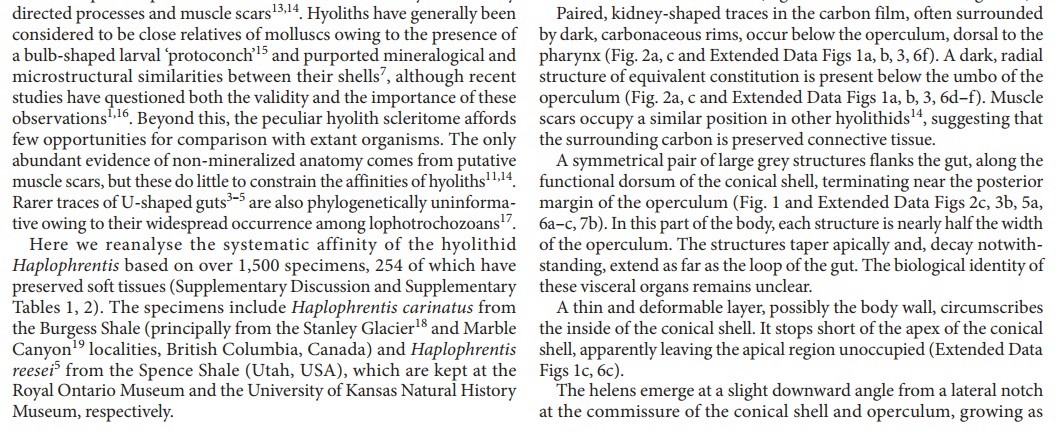

The shells of hyoliths are made from calcium carbonate as are many other marine animals such as mollusks. The large, cone-shaped shell held the animal's internal organs in life and has a hinge-like joint on the upper surface of the wide end. That hinge joined the cone to the trapdoor, technically known as the operculum, which could close completely over the cone's opening. The internal surface of both the cone and trapdoor show many attachment points for muscles, allowing the door to be opened and closed.

Poking out of a small gap between the cone and trapdoor on the right and left side were two curved elements known as “helens.” The helens are thought to have acted as stilts, and may have been mobile. They bear that peculiar name because isolated helen fossils were given their own scientific name, Helenia. Once it was determined that they were parts of hyolith shells, they were renamed helens.

The mouth of Haplophrentis was at the end of tube-shaped proboscis that could extended outside of the opened shell. At the end of the proboscis were two fleshy “wings” covered in tentacles. The gut runs along the bottom of the cone-shaped shell and takes a U-turn near the point and exits the open end of the cone above the proboscis.

Moysiuk and colleagues consider the tentacled proboscis to be an organ called a lophophore. Lophophores are specialized tentacled feeding organs that surround the mouth and are present in several aquatic invertebrate groups including brachiopods or lamp shells, and phoronids or horseshoe worms. Lophophore-bearing animals, called lophophorates, are filter feeders and the tentacles both collect and move food items into the mouth. In addition to having lophophores, all lophophorates have U-shaped guts.

The researchers found that hyoliths are most closely related to brachiopods—clam-like invertebrates with two shells joined by a hinge. The similarities are superficial however: the shells of clams are mirror images of each other, but each shell is asymmetrical. Brachiopods on the other hand, have two shells that don't look alike, but each shell has a mirrored left and right side.

Brachiopods hold on to hard surfaces by a soft tissue stalk that emerges from one of the shells near the hinge. Living brachiopods are rare on beaches and therefore rarely seen by most people, although common in deeper water. They are very well known to paleontologists however, as they're some of the most abundant of all Paleozoic fossils, and were major components of ancient marine communities.

Hyoliths lived on the sandy sea floor, with the point of the cone and helens in contact with the bottom. The open end was held above the sand and allowed the lophophore to extend beyond the shell when the door was open. Because hyoliths lived on top of the sand, they are different from most modern filter feeders of the sandy bottom, which live in burrows. Rare examples of hyoliths show brachiopods clinging to the helens. Many specimens of Haplophrentis have been found in the guts of a predatory burrowing worm called Ottoia.

Once regarded as a great paleontological mystery we now know much more about this group. This new research on hyoliths has answered many long-standing questions both anatomical and phylogenetic. The soft tissues preserved in Haplophrentis show that they are lophophore animals, most closely related to brachiopods.

These ancient ice cream cones with trapdoors were once one of many mystery animals that characterized the Cambrian Explosion, a sudden jump in diversity of animals in the Middle Cambrian. The hyoliths including Haplophrentis join the velvet worm Hallucigenia and stem arthropod Anomalocaris as former mystery animals from the Cambrian that have found their homes on the tree of life.

The Curious Case Of The Hyolith, An Ancient 'Ice Cream Cone' That's Found A Home 1

It has spent some 175 years homeless, wandering many paths of taxonomy without a single branch to call its own. In the time since it was first described, this now-extinct, cone-shaped sea creature has known a number of presumed families — from mollusks to designations much more nebulous — but the tiny hyolith never quite fit in any of them.

You'd be forgiven for thinking the hyolith — with shells that resemble an ice cream cone and two spines that sprout like curved stilts — looks a bit odd. It is partly the creature's curious combination of parts that left scientists scratching their heads.

But now, a group of researchers believes it has found the hyolith a home in scientific classification, more than 500 million years after the now-extinct organism evolved onto the scene.

Drawing on more than 1,500 specimens, the group focused closely on fossils of a particular kind of hyolith, the Haplophrentis. And in the process, they discovered something crucial: The creature had short tentacles around a centrally located mouth, tucked between its two shells.

In other words, according to the study they published in the journal Nature, the ancient organism had a feeding structure called a lophophore. The researchers believe the Haplophrentis would elevate itself from the sea floor with those stilt-like spines (also known as "helens") and use its lophophore to filter and feed on material suspended in water.

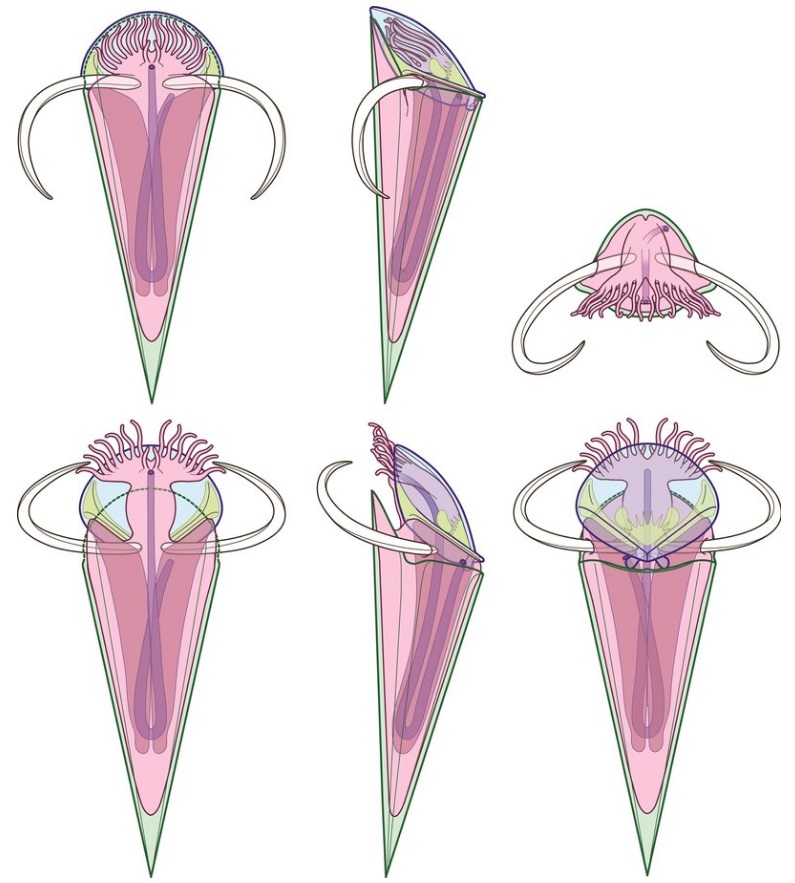

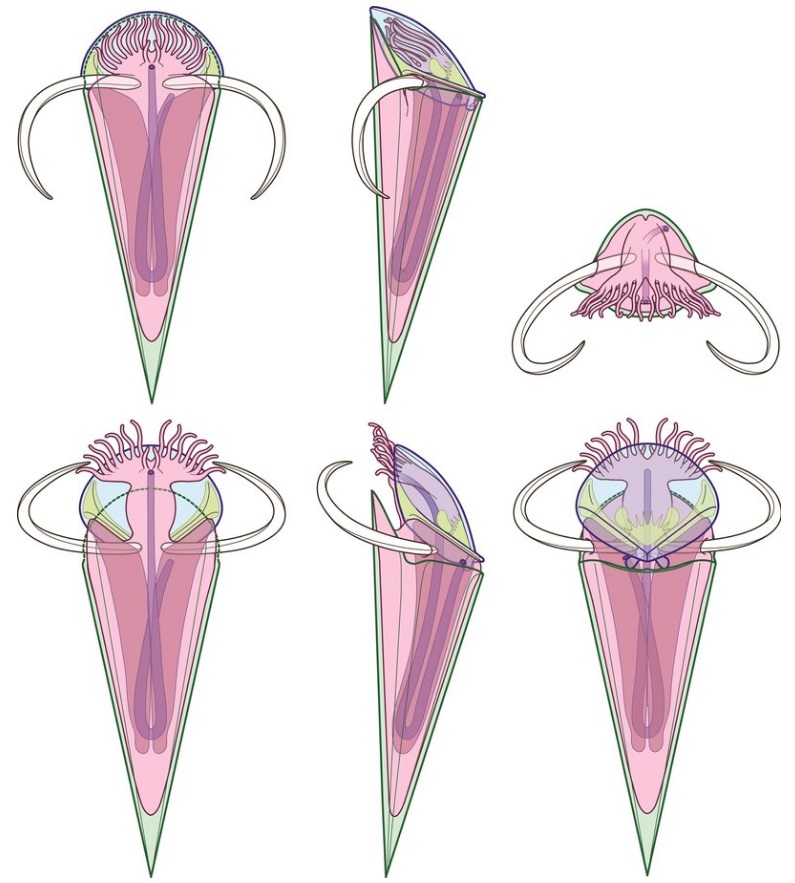

Different views of Haplophrentis. The shells are shown as see-through to render the tentacles of the lophophore visible. In the lower images, the lophophore is reaching out to feed, with the pair of spines rotated downwards to support the body.

"Only one group of living animals — the brachiopods — has a comparable feeding structure enclosed by a pair of valves," the lead author on the project, Joseph Moysiuk, told Phys.org. "This finding demonstrates that brachiopods, and not mollusks, are the closest surviving relatives of hyoliths."

The home that hyoliths can now call their own? The Lophophorata — or, the group of aquatic organisms, including brachiopods, that all share this signature organ.

The key to the discovery was the soft tissue preserved with the fossils Moysiuk and his team were studying, which were culled largely from the Burgess Shale in British Columbia. The New York Times explains:

"Typically when paleontologists find fossils they uncover the hard parts of an organism, like its teeth, bones or shells. Soft tissue is much harder to find because it does not fossilize easily. But some of the samples that Mr. Moysiuk came across had preserved soft tissue."

It was only in analyzing these "exceptionally preserved soft tissues" that Moysiuk, an undergraduate at the University of Toronto, found the tiny tentacles around the hyolith's mouth. Those soft tissues offered the crucial clue to solving a hard problem that long puzzled scientists.

"It's a real milestone," Martin Smith, a paleontologist on the research team, told The Toronto Sun. "It's enormously exciting to have solved such a major paleontological problem that has been such a mystery for so long, and I think it really does change the way we look at a large set of the fossil record."

The exact affinities of the enigmatic cone shelled hyoliths was a mystery ever since their discovery. It was long thought to be some kind of mollusks but recent investigation of specimens from the Burgess Shales with preserved lophophores show their close relationships with the Brachiopods. Hyoliths appeared in the Cambrian and went extinct at the end of the Permian.

4

1. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/01/12/509344502/the-curious-case-of-the-hyolith-an-ancient-ice-cream-cone-thats-found-a-home

2. http://www.eartharchives.org/articles/ice-cream-cone-with-a-trapdoor-finds-its-place-on-the-tree-of-life/

3. http://spinops.blogspot.com.br/2017/02/haplophrentis-carinatus.html

4. http://www.nature.com.https.sci-hub.hk/articles/nature20804

Terreneuvian Orthothecid (Hyolitha) Digestive Tracts from Northern Montagne Noire, France; Taphonomic, Ontogenetic and Phylogenetic Implications

http://reasonandscience.heavenforum.org/t2664-hyolith-an-ancient-ice-cream-cone

The hyolith Haplophrentis extends the tentacles of its feeding organ (lophophore) from between its shells. The paired spines, or "helens," are propping the animal up off the ocean floor. 2

Hyoliths, an enigmatic group of Paleozoic invertebrates have long puzzled paleontologists. A new analysis of hundreds of specimens shows that they are close relatives of brachiopods or lamp shells.

If you were to describe the shells of a hyolith to someone, they may think you're describing the home of a minor character from SpongeBob SquarePants: imagine a kind of squished ice cream cone with a trapdoor. Also, poking out of the gap in the door are two curled stilts.

As absurd as it sounds, creatures fitting that description were common in Cambrian oceans more than 500 million years ago and, although they became less common after the Cambrian, persisted until the Permo-Triassic Extinction 252 million years ago.

Hyoliths are unlike any living organisms and have puzzled paleontologists since their discovery nearly two centuries ago. Many paleontologists grouped them with mollusks, or considered them to be in their own group, with uncertain relationships to other animals.

In early 2017 paleontologists Joseph Moysiuk, Martin Smith, and Jean-Bernard Caron published a paper analyzing over 1500 specimens of the Cambrian hyolith named Haplophrentis, known from the Burgess Shale in British Columbia, Canada and the Spence Shale in Utah, USA. Both the Burgess Shale and Spence Shale are what are known as lagerstätten, rock formations that preserve fossils in exceptional detail including soft tissues.

More than 250 examples of Haplophrentis preserve soft tissues which allowed Moysiuk and colleagues to reconstruct the internal organs of the living animals and determine where hyoliths are located on the tree of life.

The shells of hyoliths are made from calcium carbonate as are many other marine animals such as mollusks. The large, cone-shaped shell held the animal's internal organs in life and has a hinge-like joint on the upper surface of the wide end. That hinge joined the cone to the trapdoor, technically known as the operculum, which could close completely over the cone's opening. The internal surface of both the cone and trapdoor show many attachment points for muscles, allowing the door to be opened and closed.

Poking out of a small gap between the cone and trapdoor on the right and left side were two curved elements known as “helens.” The helens are thought to have acted as stilts, and may have been mobile. They bear that peculiar name because isolated helen fossils were given their own scientific name, Helenia. Once it was determined that they were parts of hyolith shells, they were renamed helens.

The mouth of Haplophrentis was at the end of tube-shaped proboscis that could extended outside of the opened shell. At the end of the proboscis were two fleshy “wings” covered in tentacles. The gut runs along the bottom of the cone-shaped shell and takes a U-turn near the point and exits the open end of the cone above the proboscis.

Moysiuk and colleagues consider the tentacled proboscis to be an organ called a lophophore. Lophophores are specialized tentacled feeding organs that surround the mouth and are present in several aquatic invertebrate groups including brachiopods or lamp shells, and phoronids or horseshoe worms. Lophophore-bearing animals, called lophophorates, are filter feeders and the tentacles both collect and move food items into the mouth. In addition to having lophophores, all lophophorates have U-shaped guts.

The researchers found that hyoliths are most closely related to brachiopods—clam-like invertebrates with two shells joined by a hinge. The similarities are superficial however: the shells of clams are mirror images of each other, but each shell is asymmetrical. Brachiopods on the other hand, have two shells that don't look alike, but each shell has a mirrored left and right side.

Brachiopods hold on to hard surfaces by a soft tissue stalk that emerges from one of the shells near the hinge. Living brachiopods are rare on beaches and therefore rarely seen by most people, although common in deeper water. They are very well known to paleontologists however, as they're some of the most abundant of all Paleozoic fossils, and were major components of ancient marine communities.

Hyoliths lived on the sandy sea floor, with the point of the cone and helens in contact with the bottom. The open end was held above the sand and allowed the lophophore to extend beyond the shell when the door was open. Because hyoliths lived on top of the sand, they are different from most modern filter feeders of the sandy bottom, which live in burrows. Rare examples of hyoliths show brachiopods clinging to the helens. Many specimens of Haplophrentis have been found in the guts of a predatory burrowing worm called Ottoia.

Once regarded as a great paleontological mystery we now know much more about this group. This new research on hyoliths has answered many long-standing questions both anatomical and phylogenetic. The soft tissues preserved in Haplophrentis show that they are lophophore animals, most closely related to brachiopods.

These ancient ice cream cones with trapdoors were once one of many mystery animals that characterized the Cambrian Explosion, a sudden jump in diversity of animals in the Middle Cambrian. The hyoliths including Haplophrentis join the velvet worm Hallucigenia and stem arthropod Anomalocaris as former mystery animals from the Cambrian that have found their homes on the tree of life.

The Curious Case Of The Hyolith, An Ancient 'Ice Cream Cone' That's Found A Home 1

It has spent some 175 years homeless, wandering many paths of taxonomy without a single branch to call its own. In the time since it was first described, this now-extinct, cone-shaped sea creature has known a number of presumed families — from mollusks to designations much more nebulous — but the tiny hyolith never quite fit in any of them.

You'd be forgiven for thinking the hyolith — with shells that resemble an ice cream cone and two spines that sprout like curved stilts — looks a bit odd. It is partly the creature's curious combination of parts that left scientists scratching their heads.

But now, a group of researchers believes it has found the hyolith a home in scientific classification, more than 500 million years after the now-extinct organism evolved onto the scene.

Drawing on more than 1,500 specimens, the group focused closely on fossils of a particular kind of hyolith, the Haplophrentis. And in the process, they discovered something crucial: The creature had short tentacles around a centrally located mouth, tucked between its two shells.

In other words, according to the study they published in the journal Nature, the ancient organism had a feeding structure called a lophophore. The researchers believe the Haplophrentis would elevate itself from the sea floor with those stilt-like spines (also known as "helens") and use its lophophore to filter and feed on material suspended in water.

Different views of Haplophrentis. The shells are shown as see-through to render the tentacles of the lophophore visible. In the lower images, the lophophore is reaching out to feed, with the pair of spines rotated downwards to support the body.

"Only one group of living animals — the brachiopods — has a comparable feeding structure enclosed by a pair of valves," the lead author on the project, Joseph Moysiuk, told Phys.org. "This finding demonstrates that brachiopods, and not mollusks, are the closest surviving relatives of hyoliths."

The home that hyoliths can now call their own? The Lophophorata — or, the group of aquatic organisms, including brachiopods, that all share this signature organ.

The key to the discovery was the soft tissue preserved with the fossils Moysiuk and his team were studying, which were culled largely from the Burgess Shale in British Columbia. The New York Times explains:

"Typically when paleontologists find fossils they uncover the hard parts of an organism, like its teeth, bones or shells. Soft tissue is much harder to find because it does not fossilize easily. But some of the samples that Mr. Moysiuk came across had preserved soft tissue."

It was only in analyzing these "exceptionally preserved soft tissues" that Moysiuk, an undergraduate at the University of Toronto, found the tiny tentacles around the hyolith's mouth. Those soft tissues offered the crucial clue to solving a hard problem that long puzzled scientists.

"It's a real milestone," Martin Smith, a paleontologist on the research team, told The Toronto Sun. "It's enormously exciting to have solved such a major paleontological problem that has been such a mystery for so long, and I think it really does change the way we look at a large set of the fossil record."

The exact affinities of the enigmatic cone shelled hyoliths was a mystery ever since their discovery. It was long thought to be some kind of mollusks but recent investigation of specimens from the Burgess Shales with preserved lophophores show their close relationships with the Brachiopods. Hyoliths appeared in the Cambrian and went extinct at the end of the Permian.

4

1. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/01/12/509344502/the-curious-case-of-the-hyolith-an-ancient-ice-cream-cone-thats-found-a-home

2. http://www.eartharchives.org/articles/ice-cream-cone-with-a-trapdoor-finds-its-place-on-the-tree-of-life/

3. http://spinops.blogspot.com.br/2017/02/haplophrentis-carinatus.html

4. http://www.nature.com.https.sci-hub.hk/articles/nature20804

Terreneuvian Orthothecid (Hyolitha) Digestive Tracts from Northern Montagne Noire, France; Taphonomic, Ontogenetic and Phylogenetic Implications