The human ear , irreducibly complex

YOUR EARS ARE DESIGNED

http://reasonandscience.heavenforum.org/t1775-the-human-ear-irreducibly-complex

The ear has some of the most delicately complex structures to be found anywhere in the body. For example, consider this: Blood bathes every part of your body, and flows next to and into every cell,-with one exception: the cells in the ear which are involved in hearing. Why is that? If blood capillaries flowed next to those particular cells, you could not hear properly! You would hear the faint beating sounds of the blood rushing along as it is pushed by the heart pump. So, instead, fluids containing no blood are sent that final short distance to bathe, nourish, and clean those hearing cells.That was done by chance? There would be no reason for random activity to do that.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I5xOEVZ83Ng

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fbym23TtFWs

The Creation of the Ear

http://www.harunyahya.com/en/Books/592/darwinism-refuted/chapter/51

Another interesting example of the irreducibly complex organs in living things is the human ear.

As is commonly known, the hearing process begins with vibrations in the air. These vibrations are enhanced in the external ear. Research has shown that that part of the external ear known as the concha works as a kind of megaphone, and sound waves are intensified in the external auditory canal. In this way, the volume of sound waves increases considerably.

Sound intensified in this way enters the external auditory canal. This is the area from the external ear to the ear drum. One interesting feature of the auditory canal, which is some three and a half centimeters long, is the wax it constantly secretes. This liquid contains an antiseptic property which keeps bacteria and insects out. Furthermore, the cells on the surface of the auditory canal are aligned in a spiral form directed towards the outside, so that the wax always flows towards the outside of the ear as it is secreted.

Sound vibrations which pass down the auditory canal in this way reach the ear drum. This membrane is so sensitive that it can even perceive vibrations on the molecular level. By means of the exquisite sensitivity of the ear drum, you can easily hear somebody whispering from yards away. Or you can hear the vibration set up as you slowly rub two fingers together. Another extraordinary feature of the ear drum is that after receiving a vibration it returns to its normal state. Calculations have revealed that, after perceiving the tiniest vibrations, the ear drum becomes motionless again within up to four thousandths of a second. If it did not become motionless again so quickly, every sound we hear would echo in our ears.

The ear drum amplifies the vibrations which come to it, and sends them on to the middle ear region. Here, there are three bones in an extremely sensitive equilibrium with each other. These three bones are known as the hammer, the anvil and the stirrup; their function is to amplify the vibrations that reach them from the ear drum.

But the middle ear also possesses a kind of "buffer," to reduce exceedingly high levels of sound. This feature is provided by two of the body's smallest muscles, which control the hammer, anvil and stirrup bones. These muscles enable exceptionally loud noises to be reduced before they reach the inner ear. As a result of this mechanism, we hear sounds that are loud enough to shock the system at a reduced volume. These muscles are involuntary, and come into operation automatically, in such a way that even if we are asleep and there is a loud noise beside us, these muscles immediately contract and reduce the intensity of the vibration reaching the inner ear.

The middle ear, which is so flawless, needs to maintain an important equilibrium. The air pressure inside the middle ear has to be the same as that beyond the ear drum, in other words, the same as the atmospheric air pressure. But this balance has been thought of, and a canal between the middle ear and the outside world which allows an exchange of air has been built in. This canal is the Eustachean tube, a hollow tube running from the inner ear to the oral cavity.

The Inner Ear

It will be seen that all we have examined so far consists of the vibrations in the outer and middle ear. The vibrations are constantly passed forward, but so far there is still nothing apart from a mechanical motion. In other words, there is as yet no sound.

The process whereby these mechanical motions begin to be turned into sound begins in the area known as the inner ear. In the inner ear is a spiral-shaped organ filled with a liquid. This organ is called the cochlea.

The last part of the middle ear is the stirrup bone, which is linked to the cochlea by a membrane. The mechanical vibrations in the middle ear are sent on to the liquid in the inner ear by this connection.

The vibrations which reach the liquid in the inner ear set up wave effects in the liquid. The inner walls of the cochlea are lined with small hair-like structures, called stereocilia, which are affected by this wave effect. These tiny hairs move strictly in accordance with the motion of the liquid. If a loud noise is emitted, then more hairs bend in a more powerful way. Every different frequency in the outside world sets up different effects in the hairs.

But what is the meaning of this movement of the hairs? What can the movement of the tiny hairs in the cochlea in the inner ear have to do with listening to a concert of classical music, recognizing a friend's voice, hearing the sound of a car, or distinguishing the millions of other kinds of sounds?

The answer is most interesting, and once more reveals the complexity of the ear. Each of the tiny hairs covering the inner walls of the cochlea is actually a mechanism which lies on top of 16,000 hair cells. When these hairs sense a vibration, they move and push each other, just like dominos. This motion opens channels in the membranes of the cells lying beneath the hairs. And this allows the inflow of ions into the cells. When the hairs move in the opposite direction, these channels close again. Thus, this constant motion of the hairs causes constant changes in the chemical balance within the underlying cells, which in turn enables them to produce electrical signals. These electrical signals are forwarded to the brain by nerves, and the brain then processes them, turning them into sound.

Science has not been able to explain all the technical details of this system. While producing these electrical signals, the cells in the inner ear also manage to transmit the frequencies, strengths, and rhythms coming from the outside. This is such a complicated process that science has so far been unable to determine whether the frequency-distinguishing system takes place in the inner ear or in the brain.

At this point, there is an interesting fact we have to consider concerning the motion of the tiny hairs on the cells of the inner ear. Earlier, we said that the hairs waved back and forth, pushing each other like dominos. But usually the motion of these tiny hairs is very small. Research has shown that a hair motion of just by the width of an atom can be enough to set off the reaction in the cell. Experts who have studied the matter give a very interesting example to describe this sensitivity of these hairs: If we imagine a hair as being as tall as the Eiffel Tower, the effect on the cell attached to it begins with a motion equivalent to just 3 centimeters of the top of the tower. 351

Just as interesting is the question of how often these tiny hairs can move in a second. This changes according to the frequency of the sound. As the frequency gets higher, the number of times these tiny hairs can move reaches very high levels: for instance, a sound of a frequency of 20,000 causes these tiny hairs to move 20,000 times a second.

Everything we have examined so far has shown us that the ear possesses an extraordinary structure. On closer examination, it becomes evident that this structure is irreducibly complex, since, in order for hearing to happen, it is necessary for all the component parts of the auditory system to be present and in complete working order. Take away any one of these—for instance, the hammer bone in the middle ear—or damage its structure, and you will no longer be able to hear anything. In order for you to hear, such different elements as the ear drum, the hammer, anvil and stirrup bones, the inner ear membrane, the cochlea, the liquid inside the cochlea, the tiny hairs that transmit the vibrations from the liquid to the underlying sensory cells, the latter cells themselves, the nerve network running from them to the brain, and the hearing center in the brain must all exist in complete working order. The system cannot develop "by stages," because the intermediate stages would serve no purpose.

Evolutionist Errors Regarding the Origin of the Ear

The irreducibly complex system in the ear is something that evolutionists can never satisfactorily explain. When we look at the theories evolutionists occasionally propose, we are met by a facile and superficial logic. For example, the writer Veysel Atayman, who translated the book Im Anfang War der Wasserstoff (In the Beginning was Hydrogen), by the German biologist Hoimar von Ditfurth, into Turkish, and who has come to be regarded as an "evolution expert" by the Turkish media, sums up his "scientific" theory on the origin of the ear and the so-called evidence for it in this way:

Our hearing organ, the ear, emerged as a result of the evolution of the endoderm and exoderm layers, which we call the skin. One proof of this is that we feel low sounds in the skin of our stomachs! 352

In other words, Atayman thinks that the ear evolved from the ordinary skin in other parts of our bodies, and sees our feeling low sounds in our skin as a proof of this.

Let us first take Atayman's "theory," and then the so-called "proof" he offers. We have just seen that the ear is a complex structure made up of dozens of different parts. To propose that this structure emerged with "the evolution of layers of skin" is, in a word, to build castles in the air. What mutation or natural selection effect could enable such an evolution to happen? Which part of the ear formed first? How could that part, the product of coincidence, have been chosen through natural selection even though it had no function? How did chance bring about all the sensitive mechanical balances in the ear: the ear drum, the hammer, anvil and stirrup bones, the muscles that control them, the inner ear, the cochlea, the liquid in it, the tiny hairs, the movement-sensitive cells, their nerve connections, etc.?

There is no answer to these questions. In fact, to suggest that all this complex structure is just "chance" is actually an attack on human intelligence. However, in Michael Denton's words, to the Darwinist "the idea is accepted without a ripple of doubt - the paradigm takes precedence!" 353

Beyond the mechanisms of natural selection and mutation, evolutionists really believe in a "magic wand" that brings about the most complex systems by chance.

The "proof" that Atayman supplies for this imaginary theory is even more interesting. He says, "Our feeling low sounds in our skin is proof." What we call sound actually consists of vibrations in the air. Since vibrations are a physical effect, of course they can be perceived by our sense of touch. For that reason it is quite normal that we should be able to feel high and low sounds physically. Furthermore, these sounds also affect bodies physically. The breaking of glass in a room under high intensities of sound is one example of this. The interesting thing is that the evolutionist writer Atayman should think that these effects are a proof of the evolution of the ear. The logic Atayman employs is the following: "The ear perceives sound waves, our skin is affected by these vibrations, therefore, the ear evolved from the skin." Following Atayman's logic, one could also say, "The ear perceives sound waves, glass is also affected by these, therefore the ear evolved from glass." Once one has left the bounds of reason, there is no "theory" that cannot be proposed.

Other scenarios that evolutionists put forward regarding the origin of the ear are surprisingly inconsistent. Evolutionists claim that all mammals, including human beings, evolved from reptiles. But, as we saw earlier, reptiles' ear structures are very different from those of mammals. All mammals possess the middle ear structure made up of the three bones that have just been described, whereas there is only one bone in the middle ear of all reptiles. In response to this, evolutionists claim that four separate bones in the jaws of reptiles changed place by chance and "migrated" to the middle ear, and that again by chance they took on just the right shape to turn into the anvil and stirrup bones. According to this imaginary scenario, the single bone in reptiles' middle ears changed shape and turned into the hammer bone, and the exceedingly sensitive equilibrium between the three bones in the middle ear was established by chance. 354

This fantastical claim, based on no scientific discovery at all (it corresponds to nothing in the fossil record), is exceedingly self-contradictory. The most important point here is that such an imaginary change would leave a creature deaf. Naturally, a living thing cannot continue hearing if its jaw bones slowly start entering its inner ear. Such a species would be at a disadvantage compared to other living things and would be eliminated, according to what evolutionists themselves believe.

On the other hand, a living thing whose jaw bones were moving towards its ear would end up with a defective jaw. Such a creature's ability to chew would greatly decrease, and even disappear totally. This, too, would disadvantage the creature, and result in its elimination.

In short, the results which emerge when one examines the structure of ears and their origins clearly invalidate evolutionist assumptions. The Grolier Encyclopedia, an evolutionist source, makes the admission that "the origin of the ear is shrouded in uncertainty." 355 Actually, anyone who studies the system in the ear with common sense can easily see that it is the product of gods magnificent creation.

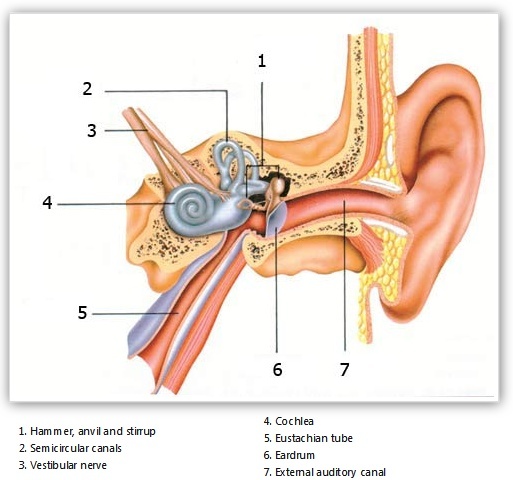

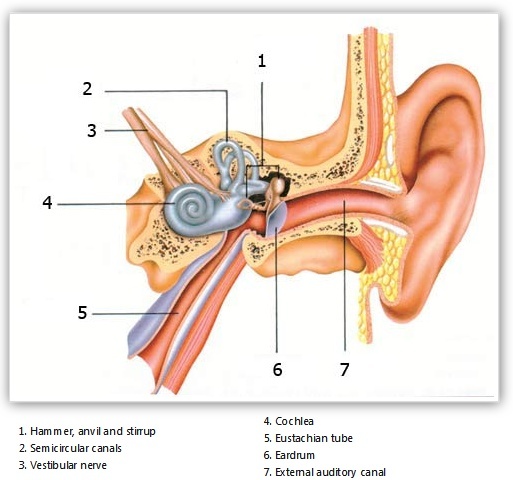

1. Hammer, anvil and stirrup

2. Semicircular canals

3. Vestibular nerve

4. Cochlea

5. Eustachian tube

6. Eardrum

7. External auditory canal

1. Utriculus

2. Common crus

3. Superior semicircular canal

4. Lateral semicircular canal

5. Ampulla

6. Posterior semicircular canal

7. Oval window

8. Vestibular nerve

9. Cochlea

10. Vestibule canal

11. Cochlea duct

12. Tympanic canal

13. Vestibular nerve

14. Sacculus

YOUR EARS ARE DESIGNED

http://reasonandscience.heavenforum.org/t1775-the-human-ear-irreducibly-complex

The ear has some of the most delicately complex structures to be found anywhere in the body. For example, consider this: Blood bathes every part of your body, and flows next to and into every cell,-with one exception: the cells in the ear which are involved in hearing. Why is that? If blood capillaries flowed next to those particular cells, you could not hear properly! You would hear the faint beating sounds of the blood rushing along as it is pushed by the heart pump. So, instead, fluids containing no blood are sent that final short distance to bathe, nourish, and clean those hearing cells.That was done by chance? There would be no reason for random activity to do that.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I5xOEVZ83Ng

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fbym23TtFWs

The Creation of the Ear

http://www.harunyahya.com/en/Books/592/darwinism-refuted/chapter/51

Another interesting example of the irreducibly complex organs in living things is the human ear.

As is commonly known, the hearing process begins with vibrations in the air. These vibrations are enhanced in the external ear. Research has shown that that part of the external ear known as the concha works as a kind of megaphone, and sound waves are intensified in the external auditory canal. In this way, the volume of sound waves increases considerably.

Sound intensified in this way enters the external auditory canal. This is the area from the external ear to the ear drum. One interesting feature of the auditory canal, which is some three and a half centimeters long, is the wax it constantly secretes. This liquid contains an antiseptic property which keeps bacteria and insects out. Furthermore, the cells on the surface of the auditory canal are aligned in a spiral form directed towards the outside, so that the wax always flows towards the outside of the ear as it is secreted.

Sound vibrations which pass down the auditory canal in this way reach the ear drum. This membrane is so sensitive that it can even perceive vibrations on the molecular level. By means of the exquisite sensitivity of the ear drum, you can easily hear somebody whispering from yards away. Or you can hear the vibration set up as you slowly rub two fingers together. Another extraordinary feature of the ear drum is that after receiving a vibration it returns to its normal state. Calculations have revealed that, after perceiving the tiniest vibrations, the ear drum becomes motionless again within up to four thousandths of a second. If it did not become motionless again so quickly, every sound we hear would echo in our ears.

The ear drum amplifies the vibrations which come to it, and sends them on to the middle ear region. Here, there are three bones in an extremely sensitive equilibrium with each other. These three bones are known as the hammer, the anvil and the stirrup; their function is to amplify the vibrations that reach them from the ear drum.

But the middle ear also possesses a kind of "buffer," to reduce exceedingly high levels of sound. This feature is provided by two of the body's smallest muscles, which control the hammer, anvil and stirrup bones. These muscles enable exceptionally loud noises to be reduced before they reach the inner ear. As a result of this mechanism, we hear sounds that are loud enough to shock the system at a reduced volume. These muscles are involuntary, and come into operation automatically, in such a way that even if we are asleep and there is a loud noise beside us, these muscles immediately contract and reduce the intensity of the vibration reaching the inner ear.

The middle ear, which is so flawless, needs to maintain an important equilibrium. The air pressure inside the middle ear has to be the same as that beyond the ear drum, in other words, the same as the atmospheric air pressure. But this balance has been thought of, and a canal between the middle ear and the outside world which allows an exchange of air has been built in. This canal is the Eustachean tube, a hollow tube running from the inner ear to the oral cavity.

The Inner Ear

It will be seen that all we have examined so far consists of the vibrations in the outer and middle ear. The vibrations are constantly passed forward, but so far there is still nothing apart from a mechanical motion. In other words, there is as yet no sound.

The process whereby these mechanical motions begin to be turned into sound begins in the area known as the inner ear. In the inner ear is a spiral-shaped organ filled with a liquid. This organ is called the cochlea.

The last part of the middle ear is the stirrup bone, which is linked to the cochlea by a membrane. The mechanical vibrations in the middle ear are sent on to the liquid in the inner ear by this connection.

The vibrations which reach the liquid in the inner ear set up wave effects in the liquid. The inner walls of the cochlea are lined with small hair-like structures, called stereocilia, which are affected by this wave effect. These tiny hairs move strictly in accordance with the motion of the liquid. If a loud noise is emitted, then more hairs bend in a more powerful way. Every different frequency in the outside world sets up different effects in the hairs.

But what is the meaning of this movement of the hairs? What can the movement of the tiny hairs in the cochlea in the inner ear have to do with listening to a concert of classical music, recognizing a friend's voice, hearing the sound of a car, or distinguishing the millions of other kinds of sounds?

The answer is most interesting, and once more reveals the complexity of the ear. Each of the tiny hairs covering the inner walls of the cochlea is actually a mechanism which lies on top of 16,000 hair cells. When these hairs sense a vibration, they move and push each other, just like dominos. This motion opens channels in the membranes of the cells lying beneath the hairs. And this allows the inflow of ions into the cells. When the hairs move in the opposite direction, these channels close again. Thus, this constant motion of the hairs causes constant changes in the chemical balance within the underlying cells, which in turn enables them to produce electrical signals. These electrical signals are forwarded to the brain by nerves, and the brain then processes them, turning them into sound.

Science has not been able to explain all the technical details of this system. While producing these electrical signals, the cells in the inner ear also manage to transmit the frequencies, strengths, and rhythms coming from the outside. This is such a complicated process that science has so far been unable to determine whether the frequency-distinguishing system takes place in the inner ear or in the brain.

At this point, there is an interesting fact we have to consider concerning the motion of the tiny hairs on the cells of the inner ear. Earlier, we said that the hairs waved back and forth, pushing each other like dominos. But usually the motion of these tiny hairs is very small. Research has shown that a hair motion of just by the width of an atom can be enough to set off the reaction in the cell. Experts who have studied the matter give a very interesting example to describe this sensitivity of these hairs: If we imagine a hair as being as tall as the Eiffel Tower, the effect on the cell attached to it begins with a motion equivalent to just 3 centimeters of the top of the tower. 351

Just as interesting is the question of how often these tiny hairs can move in a second. This changes according to the frequency of the sound. As the frequency gets higher, the number of times these tiny hairs can move reaches very high levels: for instance, a sound of a frequency of 20,000 causes these tiny hairs to move 20,000 times a second.

Everything we have examined so far has shown us that the ear possesses an extraordinary structure. On closer examination, it becomes evident that this structure is irreducibly complex, since, in order for hearing to happen, it is necessary for all the component parts of the auditory system to be present and in complete working order. Take away any one of these—for instance, the hammer bone in the middle ear—or damage its structure, and you will no longer be able to hear anything. In order for you to hear, such different elements as the ear drum, the hammer, anvil and stirrup bones, the inner ear membrane, the cochlea, the liquid inside the cochlea, the tiny hairs that transmit the vibrations from the liquid to the underlying sensory cells, the latter cells themselves, the nerve network running from them to the brain, and the hearing center in the brain must all exist in complete working order. The system cannot develop "by stages," because the intermediate stages would serve no purpose.

Evolutionist Errors Regarding the Origin of the Ear

The irreducibly complex system in the ear is something that evolutionists can never satisfactorily explain. When we look at the theories evolutionists occasionally propose, we are met by a facile and superficial logic. For example, the writer Veysel Atayman, who translated the book Im Anfang War der Wasserstoff (In the Beginning was Hydrogen), by the German biologist Hoimar von Ditfurth, into Turkish, and who has come to be regarded as an "evolution expert" by the Turkish media, sums up his "scientific" theory on the origin of the ear and the so-called evidence for it in this way:

Our hearing organ, the ear, emerged as a result of the evolution of the endoderm and exoderm layers, which we call the skin. One proof of this is that we feel low sounds in the skin of our stomachs! 352

In other words, Atayman thinks that the ear evolved from the ordinary skin in other parts of our bodies, and sees our feeling low sounds in our skin as a proof of this.

Let us first take Atayman's "theory," and then the so-called "proof" he offers. We have just seen that the ear is a complex structure made up of dozens of different parts. To propose that this structure emerged with "the evolution of layers of skin" is, in a word, to build castles in the air. What mutation or natural selection effect could enable such an evolution to happen? Which part of the ear formed first? How could that part, the product of coincidence, have been chosen through natural selection even though it had no function? How did chance bring about all the sensitive mechanical balances in the ear: the ear drum, the hammer, anvil and stirrup bones, the muscles that control them, the inner ear, the cochlea, the liquid in it, the tiny hairs, the movement-sensitive cells, their nerve connections, etc.?

There is no answer to these questions. In fact, to suggest that all this complex structure is just "chance" is actually an attack on human intelligence. However, in Michael Denton's words, to the Darwinist "the idea is accepted without a ripple of doubt - the paradigm takes precedence!" 353

Beyond the mechanisms of natural selection and mutation, evolutionists really believe in a "magic wand" that brings about the most complex systems by chance.

The "proof" that Atayman supplies for this imaginary theory is even more interesting. He says, "Our feeling low sounds in our skin is proof." What we call sound actually consists of vibrations in the air. Since vibrations are a physical effect, of course they can be perceived by our sense of touch. For that reason it is quite normal that we should be able to feel high and low sounds physically. Furthermore, these sounds also affect bodies physically. The breaking of glass in a room under high intensities of sound is one example of this. The interesting thing is that the evolutionist writer Atayman should think that these effects are a proof of the evolution of the ear. The logic Atayman employs is the following: "The ear perceives sound waves, our skin is affected by these vibrations, therefore, the ear evolved from the skin." Following Atayman's logic, one could also say, "The ear perceives sound waves, glass is also affected by these, therefore the ear evolved from glass." Once one has left the bounds of reason, there is no "theory" that cannot be proposed.

Other scenarios that evolutionists put forward regarding the origin of the ear are surprisingly inconsistent. Evolutionists claim that all mammals, including human beings, evolved from reptiles. But, as we saw earlier, reptiles' ear structures are very different from those of mammals. All mammals possess the middle ear structure made up of the three bones that have just been described, whereas there is only one bone in the middle ear of all reptiles. In response to this, evolutionists claim that four separate bones in the jaws of reptiles changed place by chance and "migrated" to the middle ear, and that again by chance they took on just the right shape to turn into the anvil and stirrup bones. According to this imaginary scenario, the single bone in reptiles' middle ears changed shape and turned into the hammer bone, and the exceedingly sensitive equilibrium between the three bones in the middle ear was established by chance. 354

This fantastical claim, based on no scientific discovery at all (it corresponds to nothing in the fossil record), is exceedingly self-contradictory. The most important point here is that such an imaginary change would leave a creature deaf. Naturally, a living thing cannot continue hearing if its jaw bones slowly start entering its inner ear. Such a species would be at a disadvantage compared to other living things and would be eliminated, according to what evolutionists themselves believe.

On the other hand, a living thing whose jaw bones were moving towards its ear would end up with a defective jaw. Such a creature's ability to chew would greatly decrease, and even disappear totally. This, too, would disadvantage the creature, and result in its elimination.

In short, the results which emerge when one examines the structure of ears and their origins clearly invalidate evolutionist assumptions. The Grolier Encyclopedia, an evolutionist source, makes the admission that "the origin of the ear is shrouded in uncertainty." 355 Actually, anyone who studies the system in the ear with common sense can easily see that it is the product of gods magnificent creation.

1. Hammer, anvil and stirrup

2. Semicircular canals

3. Vestibular nerve

4. Cochlea

5. Eustachian tube

6. Eardrum

7. External auditory canal

1. Utriculus

2. Common crus

3. Superior semicircular canal

4. Lateral semicircular canal

5. Ampulla

6. Posterior semicircular canal

7. Oval window

8. Vestibular nerve

9. Cochlea

10. Vestibule canal

11. Cochlea duct

12. Tympanic canal

13. Vestibular nerve

14. Sacculus